Abstract

Steen L. Christiansen writes his book Drone Age Cinema (2017), “Contemporary cinema is entering the drone age…What will cinema be in the drone age?”. A very economical alternative way of capturing aerial shots for (low budget) documentaries, prosumer drones became available in Turkey and globally in 2015 and were quickly integrated into documentary film production. Before the emergence of prosumer drones, aerial shots were a luxury unaffordable for all but a few high-budget documentary film productions. Drones created a threshold in Turkish documentaries: gaze (exploration of geography-nature-life-people) from above, a Renaissance of the aerial shot. In this presentation / paper I will discuss the response to this new way of seeing in Turkish documentary cinema, and the ways in which drone shots have changed the cultural and technological environment of Turkish documentary cinema.

Keywords: Documentary Film Making, Drone, Aerial Shot, Technology, Impact

Introduction

Contemporary cinema is entering the drone age. There are two entry points. The first is the inevitable integration of drones into film production. The second entry point, and the more important one, is cinema’s response and adaptation to a new cultural and technological environment. What will cinema be in the drone age? And more urgently, what will cinema be able to do our senses (Chirstiansen 2017, 1)?

As a documentary filmmaker and an academician, I have been amazed by how quickly and effectively the drones have changed the course of documentary filmmaking. In this paper I will examine the impact of drones on documentaries produced in my country.

For decades, aerial shooting was unaffordable to independent Turkish documentary filmmakers. The vast majority of documentaries produced have been low, or even no-budget productions. Renting a helicopter or small airplane was too costly. Only a few filmmakers who were able to get a sufficient budget from their sponsors could afford the luxury of capturing the “God’s eye view” of their subjects. In 2014 however, a very affordable new aerial shooting device emerged and quickly became very popular. These new aerial shooting devices, drones, quickly became a vital tool for documentary filmmakers.

Gaze upward. There’s new technology hovering on the horizon and it’s making a dramatic ascendancy. Drones are an artist’s dream medium. They allow us to explore a scene while discovering the unseen. The photographs and videos that we create are no longer constricted by human limitations. The introduction of these exciting new tools enable us to redefine contemporary imagery by giving individuals the opportunity to appreciate the breadth and scale of their world. With this incredible technology, our creative minds can take flight (Guttman 2017, introduction).

What is Drone?

Drone is originally the English word for a male bee. But in time, it has begun to be used for an aircraft with no pilot, operated from a ground control system or able to fly autonomously with a series of on-board electronics, or both (Guttman 2017, introduction). Other common terms are Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) and Unmanned Aerial System (UAS). Because of the recent media and public attention to drones, one might assume that civil drones are a new phenomenon and that such drones are a new technology. In fact, drone technology dates back to World War I. For almost a century, drones have built and used, chiefly for military purposes. In the beginning of 2000’s companies began introducing drones to civilian markets (Custers 2016, 8-12).

Commercial drones have rapidly gained popularity over the past five years. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) battery powered, camera-equipped Vertical Take-off and Landing (VTOL) machines have already affected media production (film, tv, photography etc.) and coverage. Drones have proven to be very affordable and flexible means of capturing impressive aerial footage for various areas such as film shooting, broadcasting, advertising, newsgathering and outdoor event coverage. They seem to be replacing dollies and helicopters. They are and, it seems will remain, be very popular among amateur and professional filmmakers (Mademlis, Nikolaidis, Tefas, Pitas, Wagner, Tilman. Messina 2019,147-148).

Beginning in 2010, companies involved in drone technology have made significant inroads in miniaturization, control and perception systems, and battery technologies. These improvements have accelerated the growth of civil drone technology and applications. In the book Drones and the Creative Industry (2018), José Ramiro Martínez de Dios states that “civil drones are here to stay”. They provide unseen advantages in fields such as aerial photography and filming and aerial inspections, where they have become almost irreplaceable, partly because they provide dramatic cost reductions when compared to traditional solutions. Most civil drone companies currently concentrate on aerial photography and filming. Recently, other uses, including transporting objects, logistics and precision agriculture, have begun to attract significant attention (Dios, Baturone 2018, v-vi).

Drones have a fast, highly adaptive shot setup. They are capable of hovering above a point of interest and accessing narrow spaces. They can capture novel aerial shots not easily achievable otherwise. And most importantly, they do all this at a minimal cost. Drone use among amateur and professional filmmakers is rapidly increasing. It seems that they will remain the popular tool on the block for some time (Mademlis, Nikolaidis, Tefas, Pitas, Wagner, Tilman. Messina 2019,147-148).

Modern Turkish Documentary Cinema

The Institutionalization of Turkish Documentary Cinema began with the cooperation between Suha Arın (1942 – 2004) and Çelik Gülersoy (1930 – 2003). Suha Arın studied Cinema-TV Production and Mass Communication in the US before returning to Turkey, where he began producing documentary films and lecturing at Ankara University. In 1974 The Touring and Automobile Club of Turkey, administered by Çelik Gülersoy, hired Suha Arın to produce his first documentary film, From Hatties to Hittites. This partnership between filmmaker Arın and sponsor Gülersoy gave birth to the first professional production style in the history of Turkish documentary filmmaking. Sponsored by The Touring and Automobile Club of Turkey, Arın produced several documentaries, namely The World of Midas (1975), Safranbolu: Reflections of Time (1976), The Eternal Flame of Lycia (1977), Life Drops of Istanbul (1977), Two Seasons of Urartu (1977), Forty Thousand Steps in the Covered Bazaar (1980) and Dolmabahce Palace and Atatürk (1981). From 1975 onward, Arın also produced documentaries for Turkey’s public broadcasting institution, Turkish Radio Television (TRT).

In the 1980’s Suha Arın produced documentary projects for several private and public institutions. His crew and students later formed the core of what became known as the “Suha Arın School”. This became the most influential group in the history of documentary filmmaking in Turkey, with many filmmakers following their footsteps. The best-known names of this school are Hasan Özgen, Nesli Çölgeçen, Hakan Aytekin, İsmet Arasan, Enis Rıza, Adil Yalçın, Cahit Seymen, İlhami Algör, Nalan Sakızlı and Savaş Güvezne. The period between 1974 and 1990’s is considered Turkey’s “second period” of documentary filmmaking, which in a sense developed along the lines of the Suha Arın school.

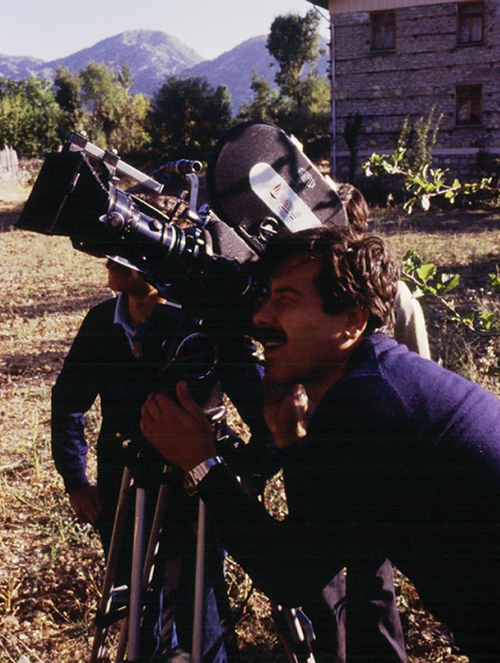

Image 2 – Documentary Filmmaker and Cinematographer Hasan Özgen shooting with Arri 16BL 16mm camera in the set of The Story of Houses in Anatolia documentary (1984)

Hasan Özgen states that documentary cinema has always had an exploratory side. This exploration - at least in the beginning was documentation-based, because the very things to be shown / explained were mostly unfamiliar, awaiting to be rediscovered visually and audially (Özgen 2019). It is no coincidence that what is considered Turkey’s “second period” of documentary filmmaking which developed along similar lines as the Suha Arın school, is chiefly cultural, historical and geographical in nature. In the 1970’s and 80’s. Documentarians of Suha Arın School explored Turkey’s geography and its culture deeply, from a local to a national scale. Suha Arın School’s main agenda was to document, to publicize and to protect the historical-cultural values and heritage of Anatolia in the modern Turkish Republic. During that period, this heritage was under the attack of right-wing politicians and their imperialist allies. They valued the modernist ideology that formed and shaped the Turkish Republic. Because the country was under the threat of populist politics, indifference and ignorance, they were anxious and determined to document every possible cultural-historical site audio-visually. The group’s efforts had a major impact on Turkey’s historical and cultural conservation programs (Özgen 2012, 1014 - 1015).

Looking into past, we can safely say that starting from Süha Arın School, Ertuğrul Karslıoğlu, Hasan Özgen, İsmet Arasan, Savaş Güvezne, Hilmi Etikan, Enis Rıza, Mehmet Eryılmaz, Haluk Cecan and many other documentary filmmakers have practiced the same poetic style which — depending on each of their specialization — later become personalized. When we look at the styles of these directors, we see more commonalities than differences.

These documentary filmmakers produced their films in the same time period. They worked on similar places. They shared a common history and literature. Their general understanding and interpretation of culture, aesthetic values and political attitude, and the way they express themselves, draw upon the same sources. They display a common consciousness not letting go of that which is disappearing, valuing that which remains, melting life experiences in the same pot (what emergence of that which is considered extinct, and avoiding elitist approaches characterized by arrogance and humiliation of the ‘other’.

…All their films are structured on preservation of culture and tradition while demanding more and better things for society. Today their films, which are very old in their format, are remain extraordinarily relevant due to their poetic style, their context and thesis (Kıraç 2008, 73 - 74).

Aerial Shots in Turkish Documentary Cinema

Historically, aerial shots in Turkish documentaries are very rare. In 1933-34, to improve Turkish–Soviet ties during the early years of the Turkish Republic, Soviet filmmaker Sergei Yutkevich (1904 – 1985) was hired to produce a documentary, Ankara: Heart of Turkey (1934), about the capital city Ankara for the 10th anniversary of the new Turkish Republic. The documentary has aerial shots of Ankara taken from a propeller plane. This was the first documentary produced in Turkey to include aerial views. In 1957 while doing his military service, accomplished master of Turkish fiction cinema Metin Erksan (1929-2012) produced a documentary film for the Turkish Air Force titled The World’s Aviators in Turkey. His long-time assistant Özlem Havuzlu notes that Erksan worked meticulously on the documentary, which he directed and edited, from 1954 to1956. Due to military restrictions, the documentary film is not available for public viewing. But based on my brief conversation with Özlem Havuzlu, it is safe to say that the aerial shots taken from military airplanes held a significant place in the documentary (Havuzlu 2019).

Documentary filmmakers during this period met the need for overhead views by taking advantage of geographical features or high buildings to take still or pan shots. The most commonly used features were mosque minarets. Generally, subjects were shot from the ground or with interior shots. The dramatic aspect, created through editing, was supported by voiceover narration. Hand-held cameras and rail-dolly systems were almost the only available methods for moving camera shots, and those operated at ground level. This all coincided with the 35 or 16mm negative film era.

In 1985, private sector helicopter service became available in Turkey. Everyone involved in filmmaking longed to shoot from a helicopter, but it was prohibitively expensive. Sponsored by Ziraat Bank, a state bank, the documentary series As the Euphrates Becomes a Lake (1985-1986) was the first documentary production that was able to include aerial shots taken from a helicopter. Suha Arın and Hasan Özgen directed the documentary series, which consisted of 10 episodes. Together with Özdemir Kalebek, Hasan Özgen was also the lead cameraman for the project and became the first documentary cameraman to shoot from a helicopter. Özgen states that the cost of renting a camera from İstanbul to take to Southeastern Anatolia was so high that they had to wait for a helicopter to be rented in the region for another job so that they could pay only for shooting time. Hasan Özgen said, “I served as director and cameraman, with 16mm negative film. Bound to a helicopter with one side entirely open, we took four hours of footage all along the Euphrates River using an Arri ST 16mm camera and mostly 10, 25 and 50mm Schneider lenses. With me was Hakan Aytekin (my assistant), constantly changing the film in a dark bag” (Özgen 2019).

With that shoot, the importance of the aerial shot ceased to be a theoretical possibility and entered Turkish documentary filmmaking as an effective visual element. The period of seeing and showing a space or objects from above as a whole had begun. This brought an entire new dimension to the portrayal of reality; Turkish documentary cinema was transitioning from still to moving and flying cameras.

With increased interest from the advertising sector, aerial shooting technology developed further; and with the appearance of camera mounts, fixing cameras to the nose of the helicopter and the increasing use of gyroscopic stabilization, it became flawless. However, the increasing expense of this technology seriously limited documentary filmmakers’ ability to exploit it.

Image 3 – Videographer Davut Dede getting ready for helicopter shooting (1995)

Concurrent with these developments was the transition from film to video. Özgen says, “The videography era was the ‘white period’. We were faced with a new production system lacking richness of color, sharpness, blacks or depth of field” (Özgen 2019). On the other hand, shooting equipment became lighter and easier to carry, and field production became easier. What’s more, these systems were becoming cheap enough to be affordable to small-scale operations.

More and more companies providing helicopters appeared, and it became possible to enrich documentaries with aerial shots, budget providing. During those years high budget documentaries and even some mid-budget documentaries had the luxury of capturing aerial shots from helicopters. STM film production company owned by Hasan Özgen and Savaş Güvezne produced two special aerial shooting projects called Bird’s Eye Turkey and Turkey from Above and went on to take aerial shots of much of the country including economic investments like dams, highways and factories as well as cities and landscapes (Özgen 2019).

The Impact of Drones in Turkish Documentary Filmmaking

The age of digital video opened a whole new world of visual possibilities. Constantly developing, with continual improvements in visual and sound recording, it not only made shooting and recording equipment smaller, it made them more democratic. Despite the fact that shooting equipment and cameras have different standards and codecs, shooting high resolution (Full HD, 2K, 4K) documentary films became a realistic, affordable possibility for nearly every filmmaker. In addition, ways and tools to apply camera movement enriched immensely by additional equipment / accessories such as action cams, gimbals, car mounts etc. Shots from the ground, the air, vehicles -almost anywhere a camera could be placed- as well as rising and turning shots, inevitably opened the doors to an entirely new way of working with visuals.

Within this new range of equipment and accessories, the drone, and prosumer drones in particular, hold a special place. Prosumer drones (DJI Phantom) penetrated the Turkish and global markets at very affordable prices in 2015, and rapidly gained great popularity among documentary filmmakers.

Helicopter shooting needed precise coordination between the pilot and cameraman, and this was no easy matter. The cameraman had to hold the camera in hand, but the helicopter was independent of the cameraman. The camera was thus bound to a double set of commands, and it was often impossible to prevent shaking and jerkiness from appearing in the footage. Compared to helicopter shooting, drones provide the ability to control the camera and the apparatus flying the camera simultaneously, which was -and is- mind blowing. A single command point and single user gives the cameraman the ability to see, shoot and correct the shot on the spot. And most importantly for cinematography, it affords the desired height and motion.

Murat Germen states that drones have more ability to access previously hard-to-reach or otherwise inaccessible places, as compared to the larger airborne vehicles such as balloons, helicopters and so on. A sufficiently skilled pilot will be able to maneuver the device within very close distances to the subject / object, and a drone offers the potential to open up new territories and reveal previously undetected sites / vantage points, exposing new parts of the world (Germen 2016, 152). For Erdem Murat Çelikler, an acclaimed Turkish documentary filmmaker of the new era, drone cinematography allows for a striking view while also capturing the location of the subject. It provides the audience with a clear understanding of the surroundings, especially in documentaries (Çelikler 2019).

Drones are more subtle, quieter, and therefore less detectable/perceptible than helicopters; this is an advantage in capturing a more candid aerial shot, especially when crowds of people are involved. Yet another advantage is that one can operate drones within buildings in order to obtain new dimensions in interior shootings (Germen 2016, 152).

On the other hand, as both Dr. Hakan Aytekin (2019) and Erdem Murat Çelikler note, there is a downside to drone shooting. It suffers from overuse, especially as b-roll recordings and transition material. This sometimes creates the feeling of pushing the audience away and keeping them at a distance from the subject. Even worse, it might appear as a gimmick. Thus, as the practice settles and creates its own conventions, comparison of innovative and effective use of drone shots and examples of distracting or disruptive shots could prove to be a valuable exercise.

Nowadays we can see drone shots in nearly every documentary film. In some documentaries they strongly complement or built up the cinematographic narration, in others they dominate the film unnecessarily or are used gratuitously. In either case, the impact of drones on documentary filmmaking in Turkey is a powerful one. It now seems that every independent documentary filmmaker is destined to be a drone pilot as well.

Image 4 – Videographer Berkay Göçer shooting with DJI Phantom 3 Pro (2016)

Conclusion

A camera that can move freely in space… What I mean is one that can go anywhere, at any speed. A camera that outstrips present camera technique and fulfills the cinema’s ultimate artistic goal. Only with this essential instrument shall we be able to realize new possibilities, including one of the most promising, the ‘architectural’ film (Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau. Eisner: 1973. p.84).

Technology and art are longtime partners. “They complement each other. Artists have always followed the advances in technology in order to be able to explore novel languages of expression, by experimenting with what innovations physically and intellectually can offer them, both during the inspiration and creation processes” (Germen 2016, 152). As documentary filmmakers we have to gaze upward. There is a new technology hovering the horizon and it’s making a dramatic ascendancy. Drones will be documentary filmmaker’s dream medium if already are not. Filmmakers are no longer constricted by human limitations. Drones will enable filmmakers / artists to redefine contemporary imagery by giving individuals the opportunity to appreciate the breadth and scale of their world (Gutman 2017, introduction).

From the beginning of civilization our ancestors have been fascinated with the sky. The skies have enchanted their imagination, and flying has been one of mankind’s oldest obsessions. After hundreds of thousands of years of looking up at the skies and saying, “only God knows the truth,” drones now allow us to see from the realm of the gods. Like the bird that carried souls to heaven in ancient Turkic belief, it carries the viewer to a multidimensional view of the geography of truth. It grants us the ability look from above, to fly…and a visual regime that, like truth itself, is never stagnant, but continually moving and flowing.

Bibliography

Aytekin Hakan. 2019. “Annotation via email sent to Kurtuluş Özgen” 11 04 2019

Çelikler Erdem Murat. 2019. “Annotation via email sent to Kurtuluş Özgen” 06 05 2019

Christiansen, Steen Ledet. 2017. Drone Age Cinema: Action Film and Sensory Assault. London, New York: I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd.

Custers, Bart. 2016 “Drones Here, There and Everywhere, Introduction and Overview.” In The Future of Drone Use Opportunities and Threats from Ethical and Legal Perspectives, edited by Bart Custers, 4 -19. Berlin Heidelberg: Asser Press Springer-Verlag GmbH

De Dios, José Ramiro Martínez. Baturone, Anibal Ollero. 2018. “Foreword”. In The Drones and the Creative Industry, edited by Virginia Santamarina-Campos, Marival Segarra-Oña, v-vi. Springer Open

Eisner, Lotte H. 1973. Murnau. Berkeley & Los angeles: University of California Press

Germen, Murat. 2016. “Alternative Cityscape Visualisation: Drone shooting as a new dimension in urban photography” presented in Electronic Visualisation and the Arts Conference (EVA 2016) London, UK, 12 - 14 July 2016

Guttman, Chase. 2017. The Handbook of Drone Photography: A Complete Guide to the New Art of Do-It-Yourself Aerial Photography. New York: Skyhorse Publishing

Havuzlu, Özlem. 2019. “Telephone conversation between Özlem Havuzlu and Kurtuluş Özgen” 11.05. 2019

Kıraç Rıza. “Estetik Üstüne Meltem”. In the Belgesel Sinema 2008, edited by Uğur Kutay. İstanbul, Belgesel Sinemacılar Meslek Birliği Yayını, 2008, S 69 -79, ISBN 978-9944-0060-1-9

Özgen, Hasan. 2019. “Annotation via email sent to Kurtuluş Özgen” 14 04 2019

Özgen, Kurtuluş 2012. “The Cinematographic Horizon of Documentary Filmmaking: The impact of HD Video Technology”. Communication presented in AVANCA | CINEMA 2012 – International Conference Cinema – Art, Technology, Communication, Avanca, Portugal, 24-28 July 2012

Mademlisy, Ioannis. Nikolaidisy, Nikos, Tefas, Anastasios. Pitas, Ioannis. Wagnerz, Tilman. Messina, Alberto. 2019. “Autonomous UAV Filming in Dynamic Unstructured Outdoor Environments” in IEEE Signal Processing Magazine Volume: 36, Issue 1: 147 – 153.

Smith, Colin. 2016. The Photographer’s Guide to Drones, California: Rocky Nook

Filmography

As the Euphrates Becomes a Lake (1985-1986)., Directed by Suha Arın, Hasan Özgen

Ankara: Heart of Turkey (1934)., Directed by Sergei Yutkevich

Dolmabahce Palace and Atatürk (1981)., Directed by Suha Arın

From Hatties to Hittites (1974)., Directed by Suha Arın

Forty Thousand Steps in the Covered Bazaar (1980)., Directed by Suha Arın

Life Drops of Istanbul (1977)., Directed by Suha Arın

Safranbolu: Reflections of Time (1976)., Directed by Suha Arın

The Eternal Flame of Lycia (1977)., Directed by Suha Arın

Two Seasons of Urartu (1977)., Directed by Suha Arın

The Story of Houses in Anatolia (1984)., Directed by Suha Arın

The World of Midas (1975)., Directed by Suha Arın

World’s Aviators are in Turkey (1957)., Directed by Metin Erksan