Abstract

The paper presents an on-going research project aimed at exploring the fast modifications in the area of audiovisual communication and of the moving image. The combination between the ubiquity, ease of access, improved capacity of ‘self-producing’ audiovisual artifacts, and the medium’s communicative force and interactivity, have opened a completely new season for this domain of communication.

A key aspect is a relevant shift in the way information is delivered. One can today witness a migration process in which contents that were traditionally delivered in the most diverse formats tend to be re-packaged into audiovisual form. In this framework, the formulation of the audiovisual artifact as an individual, independent piece is increasingly being questioned in favour of the communication landscape described by Henry Jenkins as transmedial: an online distributed space, populated by intertwined multi-media contents. This not only produces a massive proliferation in the available information in audiovisual (or ‘multimedia’) format, but greatly impacts the foundations of the moving image as a language.

Thanks to a grant from our Regional government we are currently developing an experimental research project for an exhibit on the historic Museum of Alghero 19th century city’s prison. A unique opportunity of exploring the interactions between the physical and intangible dimensions of information design, the project revolves on a series of exhibit displays, populated by short audiovisual artifacts that either revisit audiovisual narrative formulas such as the documentary and the historical reconstruction, and venture to emerging hybrid formulas such as interactive augmented reality.

The paper describes the first outcomes of this ongoing research within an exhibit project that integrates space, interactivity, real artifacts and digital storytelling, taking into scrutiny the evolving role of moving image artefacts in the emerging scenario of hybrid communicative environments.

Keywords: Transmedia, Audiovisual Communication, Exhibit Design, Digital Storytelling, Media Hybridization

Introduction

The growing diffusion of portable smart devices and the increased ease of connectivity to multimedia network platforms are opening a new season for the audiovisual medium, that has in fact entered into our everyday experience with unprecedented pervasiveness.

Graphic or filmic contents, traditionally confined within well-defined boundaries, are gradually been replaced by new informative objects and are increasingly being re-packaged in multimedia format. The result is a scenario – unimaginable only a few decades ago – in which visual communication is increasingly characterized by a constant and multiform presence of the moving image. The stream of audiovisual materials – narratives, information, images – in which we are today immersed, produces a totally new state of things in which the traditional boundaries between the author and the audience are increasingly blurring. Furthermore, the very practice of sharing and creating information on social media, so characteristic of our times, tends to introduce a new space in which the real and virtual dimension overlap, interacting in new and unexpected ways (Baudrillard 1996, Flusser 2004).

Among the effects of this state of affairs, an unprecedented shift in our present space-time dimension stands out, as other spaces and times are virtually brought to us. Reissued in audiovisual form, these entities are in fact ‘transported’ here, increasingly in contexts that are no longer those specifically assigned to their fruition (the cinema, our domestic TV, the new portable smart devices) with a growing effect on our perception of the present (Flusser 2009). This, besides transforming our understanding of the audiovisual medium (and of the world as we know it) per se, leads us to investigate the ways of the complex emerging dialogue between ‘real and virtual’ (terms whose very status is into crisis, and ought be re-thought in the presence of their complex mutual contaminations). More specifically, in a scholarly perspective, it appears to us particularly stimulating the idea of exploring the opportunities of interweaving and hybridization opened by these new tools and their new uses, in order to put them to use in the evolving arena of communication design.

On these grounds, the research path we have followed within our AnimazioneDesign lab. stresses on the potential of such contaminations in a domain – that of exhibit design – in which the coupling of diverse elements such as space, tangible artefacts, visual communication, with the moving image and of audiovisual artefacts is extremely fertile.

Over the last few years, through a series of projects, we have decided to start the exploration of an ‘extended’ domain of communication design, capable of referring to a wide arena of different audiences (in terms of age, background and culture), orchestrating a multiplicity of approaches through which respond to the varying degrees of attention, interest and understanding abilities of our potential public.

Various previous experiences have allowed us to practically confront with this idea. Among these, the development of a family of audiovisual idents for the participation of the Sardinia Regional Government to Milan’s EXPO in 2015, or the design of a multi-screen presentation for the ‘Past Future’ exhibition at Milan’s Triennale, as part of the 2016 Milano Design Week (Ceccarelli, in print). The experience of both projects, which dealt extensively with the idea of combining the “physical” and “virtual” data, hybridizing audiovisual products and display solutions, confirmed being a powerful communicative solution.

Audiovisuals in hybrid exhibit environments

Beyond having general effects on the foundations of the moving image as a language, the evolving scenario we have so far described highlights stimulating directions in unexpected approaches to the audiovisual medium. In this respect, it is at this point useful to point out that our main research aim is not to develop audiovisual material per se, but as part of a more comprehensive approach in which it becomes necessarily part of a wider kind of exhibit mise en scene.

Our work in the area of the moving image is therefore primarily focused on developing short, modular, audiovisual artefacts, each of which takes advantage of one or more features of the film language: its narrative formulas, the editing pace, the communicative effects of coordinating shapes and images, often at the same time and on more than a single screen. Within the overall design goals of a given project, each module is then meant to interplay in a dialogue based on the possible interactions (formal, of meaning, or both) with the other elements that constitute the exhibiting strategy. In this framework the spatial dimension, and hence the actual disposition of the artefacts, clearly becomes a key element in the overall communication approach.

Exhibit displays and audiovisuals: some background

Our work in this field necessarily relates on the directions traced in early research exploring the possible interactions between the audiovisual and spatial dimensions. In their own specificity – and despite their very different approach – the following three examples, we believe, can help us presenting a meaningful range of possible approaches in the field, sketching at the same time the boundaries of a wide, articulated, and extremely stimulating territory.

Studio Azzurro, historic Italian video art and interactive multimedia ensemble, started its activity in the early 1980s, following the creative components of the social and political opposition movements in Italy in the 2nd half of last century. Pursuing the quest for “new models of diffuse creativity (outside the art system) suggesting new communication systems (freed from power control and from media manipulation)” (Ugo La Pietra), but leaving aside the movement’s more decidedly political-social accents, the studio started investigating the emerging medium of video. Based on previous research on architecture, urban space, and on forms of public participation, Studio Azzurro research started focusing on the interactions between video languages and space, a research that lead to a variety of projects in the domains of theatre, site-specific installations, cultural, exhibit and museum projects.

In The swimmer (1983-4), the first of a series of multi-screen video installations by the Milanese-based studio, a row of 12 parallel monitors placed horizontally one next to the other in a dark room to form a long video strip, displays the image of a man swimming in a pool. The figure crosses the virtual linear space presented by the monitor strips, passing in perfect sync from one screen to another. The achieved final effect produces a stunning spatial integration between the narrative spaces of film and the installation’s physical dimension.

Following this first piece, the creative team started developing “increasingly complex, interactive ‘video-environments’ that incorporated the visitor into the execution of their work. Taking as their point of departure the passage of objects, actions and images between spaces, Studio Azzurro’s earlier explorations with a video focused on electronic mediation apparent ‘alteration’ of the ‘real’ object or event” (Kaye 2007, 123).

The work of Jeffrey Shaw, a leading figure in new media art, investigates in inspiring ways how research and art can be combined in the interactions between the audiovisual and spatial domains. Shaw’s celebrated 1988-91 interactive installation Legible City, is a responsive environment in which a sophisticated technological setup can be accessed with an astonishing simple and straightforward interface. Legible City allows users to explore three urban environments (Manhattan, Amsterdam and Karlsruhe) virtually reconstructed by means of metaphoric huge three-dimensional letters. The letters, that simulate actual buildings in the city, are composed after text written and compiled by Dirk Groeneveld.

In order to explore the piece, users ride a conventional bicycle arranged to interact with the virtual environment. The act of pedaling, stopping and turning the bicycle’s handlebars runs the system presenting the users with the experience of a journey through a urban space virtually made ‘legible’.

As Shaw himself has highlighted, this solution allowed the audience to be “transposed into the virtual environment, creating a kinesthetic conjunction of the active body in the virtual domain” (Shaw).

With his pioneering work on ‘artificial reality’, American computer artist Myron Krueger has been among the very first authors to experiment both with the technology and with the epistemology of virtual spaces. One of Krueger’s most well-known projects, VIDEOPLACE, started in the mid ’70s of last century, presented a multi-user environment in which users could virtually interact with one another in a very natural and straightforward way. Users could explore a series of virtual sets by moving their own bodies, whose silhouettes where transferred to a large video screen. Once created, these virtual places allowed them to interact in real time with a series of visual effects or with other users, connected in separate rooms or even remotely.

Possibly the very first multi-user virtual world, Krueger’s installation totally relied on a video screen projection displaying a very simple set of visual effects – but for as simple as this may appear to us today, this basic screen surface demonstrated how from then on, completely new kind of ‘places’ or environments could be generated by the interactions and experiences of different users remotely inter-connected (Rheingold 1992).

The above three examples present possible approaches to anyone interested in exploring the audiovisual language as an intermediate space of relationship, which can be unfolded among the ‘things’, ‘signs’ and ‘languages’ that make up a project, that through a hybrid approach to designing a communicative environment, can establish new relationships between the real and virtual dimensions.

Within this communication strategy, the audiovisual language established itself, literally, as a medium, as audiovisual contents can be exploited to permeate the whole environment, re-connecting its different components and providing depth to the visitor’s experience. Moreover, due to their specific character, the communication capacity of audiovisual artifacts takes place outside and beyond the physical and temporal constrains of an exhibition: they anticipate and follow it, extending their more traditional usability as the result of their ubiquitous availability.

The Sidewalk Museum

In the track of this research work, the project we wish to present here – the ‘sidewalk museum’ – is a development in the audiovisual domain of an experience we carried out last year to promote Alghero’s Prison Museum.

The small collection incorporates a series of historical artefacts: documents, uniforms, tools, utensils and so on rescued by some of the prison’s guards. As Alghero’s prison is still fully operative, the visit to the museum – hosted in a historical section of the building (whose opening dates back to 1868), loosely modelled on the Panopticon, introduced by at the end of the 18th century (Bentham 1983) – is severely restricted for the general public.

The Museum can then be only accessed during the event ‘Monumenti Aperti’ (Open Monuments), in which over a weekend, specific sites of interest usually unaccessible are opened to the public.

The high degree of interest generated by the event – associated with the strict conditions required for entering the building (visitors are requested, on arrival, to register, present their ID, leave personal items such as keys, mobile phones and so on…) – have in the recent past produced slowdowns, bottlenecks and long queues at the entrance of the structure.

In order to overcome the long waiting times, we came up with a design proposal – the ‘sidewalk museum’ – located immediately outside the prison’s wall. Our custom-made proposal took the form of a set of ‘exhibition stations’, exhibit modules inspired by a portable device (part of the museum collection) for delivering food rations within the prison’s branches. Replicating some aspects of this original device, the displays we designed integrate physical elements, graphics, multimedia in a single shape. Although looking similar, once opened, the display unfold to perform different exhibiting function offering some synthetic introductory themes to the visit.

Image 1 – Scale models of the display stations and iconographic reference materials.

Positioned immediately outside the prison’s entrance, on the sidewalk where the queuing public awaits to begin its visit to the actual museum, the stations are thought to complement and enrich the experience of the visit before, during and after, inside and outside the building.

The displays are also a kind of ‘surprise boxes’, capable to attract and engage the public through an imaginative, metaphorical, and sometimes even ironic key.

For each of the displays a volunteer, usually a student from the local Art School, is in charge of introducing the topic treated by the ‘station’ on the grounds of the information we have arranged.

Audiovisual hybridizations

Thanks to a grant from Sardinia’s Regional Department for Culture we have been able to integrate this initial project with a research in the area of audiovisual experimentation, specifically focused on exploring the possible integrations between the audiovisual medium and the physical exhibit artefacts.

Still in progress at the time of writing, the project concerns the design and production of a series of short audiovisuals, aimed both at enriching the existing exhibition and at expanding it to shape it, well beyond the original function of supporting the Alghero ‘Monumenti Aperti’ event, into a larger, comprehensive ‘turnkey’ traveling system.

The audiovisual contents we are working on include traditional documentary material, either based on archive footage and on original material we are currently shooting; theatrical ‘installation-like’ mise en scene solutions that originally combine historic material; an augmented reality interactive informative piece based on interactive CGI reconstructions.

Our research on the potential of ‘multimedia’ integrations between the tangible and intangible dimensions of communication is aimed at defining a fluid environment where a dialogue between the physicality of the exhibit spaces and modules and the potential of audiovisual narratives can take place in new and compelling ways.

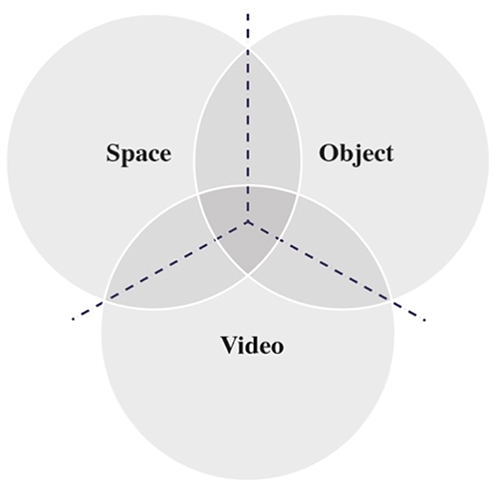

The mutual relationships space, object and audiovisual components on which our research is based can be summarized in the following diagram.

Image 2 – Diagram illustrating the relationships between space, object and audiovisual components in the project.

Along this line of reasoning, among our project’s goals are the combination of various audiovisual materials: archive footage, new ones, CGI imagery, and so on, to shape an ensemble which can be embedded into the physical nature of the exhibit, according to the same logic of the assembly that includes and incorporates pieces, signs and the carry-overs of the “real” as noted by Rosalind Krauss in her discussion about the nature of ‘drawing’ / ‘reporting’ of photography (Krauss 1996).

In this perspective, once given the status of object-space the exhibit displays incorporate components, or ‘signs’, from different realities, resulting from an assembly of materials of various origin and nature – ready-made, reproductions, more or less insightful references to other times and places. This assembly operation ends up incorporating the audiovisual artefacts we are developing, either encapsulating or projecting them onto, in, or around the surfaces of the exhibiting displays. What happens then is that, on the grounds of something that acts as a ‘reversed movement’ to what has been advocated by film theory since its very beginnings (Ejzenštejn 2004), the editing logic characteristic of the filmic language reverberates on that of the exhibit’s spatial and object composition, producing a short circuit due to hybridization, or to mutual interference.

This arrangement forces both the display device and the exhibition space to compete with the modern construction of the experience (Benjamin 1966) which is modeled precisely on the photographic and filmic one.

The audiovisual ‘treatment’ hence ends up questioning the nature of the display devices which can then work as a void place, an open box where different, ‘other’ signs as well as spatial and temporal fragments, can be aggregated along with the overall directions defined by the design brief. As a result, the hybrid combination of the audiovisual artefacts, the graphical and spatial solutions and the exhibiting system end up shaping an integrated sign group: a fully ‘meaningful environment’ built on a continuous dialogue among different media.

Transmedia

Among the effects of the significant technological transformations that have recently affected the field of communication, a key new scenario is generated by the emergence of a gradual tendency towards the integration or ‘convergence’ between different media. Within this general trend, an approach that promotes coherent but non-linear narrative modes, associated with the idea of ‘transmedia’ communication described by Henry Jenkins, has made its way within the world of communication as a whole (Jenkins 2007).

Structured as multiple stories, both for the use of different media supports and for the increasingly direct involvement of the users-viewers, transmedia eases the development of relevant and compelling contents. The narrative resulting from this scheme develops through the interactions of contributions from various types of media such as those of textual, iconic, filmic, or those produced through interactive gaming platforms. The mutual interrelations and complementarity in the convergence between such information allows the activation of spaces for developing alternative narratives.

Through such integration of elements (or ‘new information’) in something that goes beyond the mere translation of the same content from one media to another, this new approach greatly empowers the audience’s experience and participation, even in the creation of completely new contents, shaping a common, dialogic and open space. The user can, therefore, experience this new space by either following existing routes – those traced with greater evidence and more commonly pursued – or other unexpected, alternative paths.

What traditionally was an indefinite audience, has hence turned into a community of individual, but inter-connected users, that can now identify their own personal points of access to an expanded communication area. In the emerging scenario of social networks, this radically questions the traditional barrier between author and spectator, allowing the ‘viewers’ to potentially turn into co-authors, among many others, and contributing at various levels to the creation of new contents.

Keeping in mind this emerging scenario, our project interplays with the idea of empowering the overall narrative effect by composing different voices and by taking advantage of the combination of a multiplicity of different languages.

The general narrative scheme which defines our project draws on the convergence of signs, media elements and of different ‘products’, either physical and virtual. These collaborate in defining a ‘place’ for the continuous cross-contamination of different messages.

The key difference between our approach and that of a classic transmedia scenario can be summarized as follows. Where the transmedia format usually takes mainly place in the dialogic, although highly connected – and to some extent ubiquitous – world of networked social media, our design is based on a synchronic, ‘live’ and site-specific environment. In this context our approach is based on triggering the visitors’ active presence and participation, ultimately relying on their word of mouth within the limited space of an event lasting one day and a half.

Images 3-4 – Our display stations in use during the ‘Open Monuments’ event.

Some examples

We would like here to present some of the design solutions we have devised for our exhibition display that incorporate, at different levels, audiovisual contributions.

The Photobooth display. This first artefact presents a selection of early 20th-century signage photographs which are part of the museum’s collection. The images, negative photographic plates, were taken just before the release of the inmates, so they depict men that although in their very last days of imprisonment are getting ready to go back to liberty. The pictures are fascinating, either for their photographic quality and for the strong feeling of humanity they convey.

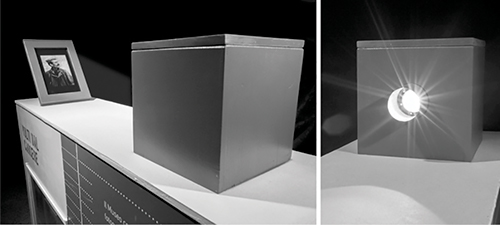

The display we have arranged presents a pretend projector – whose actual appearance is intentionally fake – coupled with a slideshow presented on a tablet’s screen. The synchronization between a flashing lamp in the projector and the slideshow produces the illusion of a live projection in which the faces of prisoners from the beginning of the 20th century appear to emerge, literally coming to life.

The side of the exhibiting display hosts series of plexiglass replicas of the original negative glass plates, which can be viewed thanks to a natural light back illumination.

Image 5 – Samples of the replicas of the original signage glass negative plates.

Image 6 –The exhibit station dedicated to prison signage photographs intentionally designed to allude to the early wonder-shows at the origins of photography and cinema.

The Tattoo station. A different formula of integration among audiovisual contents and our exhibit animates a second station exploring the theme of prison tattoos. Whereas this ancient form of communication is today very popular, tattoos were once traditionally confined within specific social groups, such as sailors and criminals and prostitutes, and inmates, of course.

In the very specific universe of prison life in fact, the habit of having tattooed fragments of one’s biography meets the crucial need to convey key facts such as criminal status or the position in the prison’s highly hierarchical structure, the kind of crime committed and so on.

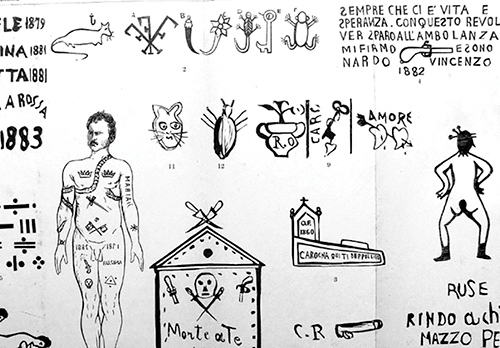

In the second half of the 19th century, Cesare Lombroso, founder of the Italian positivist criminology school, developed a theory establishing a direct connection between the somatic traits of individuals and their social attitudes (Lombroso 2013). Lombroso devoted a great deal of, almost maniacal, attention to the language of tattoos, by thoroughly recording those of hundreds of the inmates of his time. Part of this research was published in the 1897 and last edition of his famous L’uomo delinquente (The Criminal Man). The book includes a repertory of symbols and signs, presented in form of a description of the criminal attitudes of the various inmates.

The complex semantic function of the language of tattoos in the criminal world is still very actual, as described more recently in the documentary film by Giuseppe Di Vaio and Brian Anastasio, Mamma vita mia (Mom my life), and in the vast photographic records that Arkady Bronnikov collected in the prisons of the former Soviet Republic (Bronnikov 2016)

Our ‘tattoo station’ combines the photographic reproduction of self-made tools clandestinely produced by the inmates, part of the Alghero museum collection, with an audiovisual artefact that presents a series of the classic prison tattoos from the Lombroso collection. The choice of Lombroso’s quasi-iconic repertoire to illustrate the symbolic universe of tattoos is connected with the aim of presenting this topic in a non-pedantic way. These true echoes of memories now lost and silent, imprinted on the living skin, break out symbolically in the exact place where maximum control over the human body is imposed (see the prison bio-power, Foucault 1976).

Image 7 – Tattoo illustrations from C. Lombroso, L’uomo delinquente, 1897.

Beyond the original beauty of the images themselves, our aim was to highlight their universal function of recording memories, images and stories. In the short film embedded within our tattoo exhibit station, all of those signs surface as if they were on a palimpsest representing the many micro-stories of the inmates.

The introductory and augmented reality displays. Two last displays, still under development, cover other topics through two almost opposite approaches to the language of audiovisuals.

The first display presents the history of the prison reality in Sardinia, highlighting the singular vocation of the island which, for its isolation and distance from the mainland was, as a nineteenth-century official wrote, “born as place of punishment” (Mele 2004).

The narrative is left to an average documentary, presented by a neutral voiceover, in which the narration of the main events and places of this peculiar history is produced through a combination of archive material (Gazale and Tedde 2016), original footage shot on site, and classic animated diagrams and animations.

Images 8-10 – Frames from the introductory documentary about prisons in Sardinia.

A second display is aimed at describing, through a review of the evolution of the basic prison typologies, the transformation in the relationships between society and the idea of punishment.

This topic was covered in the original design for the exhibit through four very simple scale maquettes describing some key steps in prison organizational models, from the early schemes of former convents or fortresses turned into prisons, to the prisons built on the principles of the Panopticon, to contemporary models of ‘open’ prisons.

We have decided to implement this same idea through an augmented reality display that will allow the users to explore interactively through a series of tablets, individually or in small groups, 3D CGI reconstructions of the models. The system we have selected for this implementation will keep some degree of co-presence between simple reference solid models, which will be presented on top of the display, and a series of virtual reality-based simulations and short animated sessions, providing additional information.

Conclusions

Recent research carried out within our research unit, has allowed us to pursue the exploration of the expanded potential of the audiovisual medium in the contexts of temporary exhibits.

The audiovisual medium – not intended as per se, but as part of an articulated hybrid communication strategy – can constitute, especially when taking into account the current context of transmedial communication, an intermediate field in which the different display artefacts that shape an exhibit interplay within a fluid, intermediate dimension. Our current experience in designing a sidewalk museum for Alghero’s Prison is a unique opportunity to explore the interactions between the physical and virtual components of the design for an exhibit.

In this project, through the design and production of a series of short artifacts, we are testing the power of the audiovisual medium in terms of threshold. By acting ‘across the screen’, the audiovisual language becomes in fact an interface between the two narrative spaces of filmic storytelling and of the scenographic exhibiting. The various design solutions we have devised in the course of this project, combine these two worlds aiming to explore the nature of this interface, empowering the Museum’s audience engagement.

Postscript

The research ‘Schermi a scacchi’ was made possible also thanks to a contribution from the Autonomous Region of Sardinia for “studies, research and experimentation projects on new audiovisual languages and technologies” (L.R.15,2006).

Bibliography

Benjamin, Walter. 1966 (1955). L’opera d’arte nell’epoca della sua riproducibilità tecnica. Arte e società di massa. Torino : Einaudi.

Foucault, Michel. 1976. Sorvegliare e punire. Nascita della prigione. Torino : Einaudi.

Bentham, Jeremy. 1983 (1838-43). Panopticon ovvero la casa d’ispezione, edited by Michel Foucault and Michelle Perrot. Venezia : Marsilio.

Rheingold, Howard. 1992. Virtual reality. New York, N.Y. : Simon & Schuster.

Baudrillard, Jean. 1996. Il delitto perfetto. La televisione ha ucciso la realtà? Milano : Raffaello Cortina.

Krauss, Rosalind. 1996 (1990). Teoria e storia della fotografia. Milano : Bruno Mondadori.

Ejzenštejn, Sergej M. 2004 (1985). Teoria generale del montaggio. Venezia : Marsilio.

Flusser, Vilém. 2004. La cultura dei media. Milano : Bruno Mondadori.

Mele, Franca. 2004. “L’Asinara e le colonie penali in Sardegna: un’isola penitenziaria”. In Le colonie penali nell’Europa dell’Ottocento, edited by Mario Da Passano, 189–213. Roma : Carocci.

Jenkins, Henry. 2007. Cultura convergente. Milano : Apogeo.

Kaye, Nick. 2007. Multi-media: Video – Installation – Performance. Abingdon : Routledge.

Flusser, Vilém. 2009 (1985). Immagini. Come la tecnologia ha cambiato la nostra percezione del mondo. Roma : Fazi.

Lombroso, Cesare. 2013 (1897). L’uomo delinquente. Quinta edizione-1897. Milano : Bompiani.

Bronnikov, Arkady. 2016. Russian Criminal Tattoo. Police Files Vol. 1. London : Fuel Publishing.

Gazale, Vittorio and Tedde, Stefano A. 2016. Le carte liberate. Viaggio negli archivi e nei luoghi delle colonie penali della Sardegna. Sassari : Carlo Delfino.

Ceccarelli, Nicolò. “Playing with the Fairies, an experiment with Animated Environmental Communication”, in CIDAG 5 – International Conference in Design and Graphic Proceedings, in print.

Ceccarelli, Nicolò. “Images of identity: exploring local identity through visual design”, in IMG 2019 Conference, in print.

Filmography

Mamma vita mia. Criminal history tattoo Napoli. (2018). Directed by Giuseppe Di Vaio. Italy : Napoli Photo Project and MG Film.

Webgraphy

http://ugolapietra.com/anni-70/

https://www.jeffreyshawcompendium.com/portfolio/legible-city/