Abstract

Expanded cinema was proposed in 1970 by Gene Youngblood as a counterpoint to the growing consumption of commercial entertainment cinema, which, in the author’s view, fails to offer content that fosters reflection on the bond between the individual and their surrounding environment. Art has the power to provoke such cogitation in its audience, and cinema, as an artistic medium, can be a valuable tool. The multidisciplinary nature of expanded cinema allows it to draw upon tools from various art fields, with a particular focus in this study on the performing arts and game design. Our art-based research involves the development, exhibition, and study of a small number of artworks that free film from its conventional screen and the audience from their common passive role. We use mixed-reality technologies to expand the boundaries of the traditional screen, allowing the audience and the artwork to share the same metaphysical space. Each artwork incorporates darkplay, in the provocative exploration of the audience’s lack of knowledge about all of the artwork’s dimensions and functioning. However, the audience’s participation and agency allow them to uncover these, potentially leading them to reconsider the consequences of their actions within the spatial and temporal boundaries of the artworks. This reflective stance can be seen as a metaphorical representation of the human life experience, guiding its audience through considerations about their surrounding relationships, and offering a new dimension to the expansion of the artwork.

Keywords: Expanded Cinema, Audience Participation, Agency, Darkplay, Mixed-reality.

1. Introduction

Expanded cinema took shape in the 1960s and 1970s during significant artistic and social change, reflecting artists’ dissatisfaction with profit-driven commercial cinema (Youngblood 1970). It delved into traditional conventions – narrative, aesthetics, and projection – encouraging audiences to engage, to become agents. It is an aesthetic, conceptual cinema: its films, both in content and form, are a unique experience arising from the subjectivity of each person willing to understand its abstraction. This form of cinema expands the roles of the artist, the film itself, the screen, and the audience, which usually acts as a passive spectator. In an era of high mediatization, in which it is now possible to experience cinema that is not confined to a rectangular screen, it is interesting to revisit the methods of expanded cinema artists. As this is a cinematic variant influenced by many artistic fields, this study embraces the concept of site-specific installation or performance, originating from the performing arts, as well as ideas arising from game design, such as agency – in this case, the spectator as an agent – and darkplay – the subversion of the spectator’s expectations that provokes and encourages them to explore the dimensions, limits and logic of the piece, to understand the universe of the artwork and its role as an integral part of the work.

Besides this Introduction, this paper is structured into four major sections: Section 2 focuses on the history of expanded cinema, exploring the intentions and motivations of its artists and their creations, aiming to establish this research’s contextual, bibliographical, and literary foundations; Afterwards, Section 3 presents the methodology employed in this research; in Section 4 we examine the artifacts in development, starting from their conceptual origins to their current state – we reflect on the results obtained so far and those expected in the future, analyzing their meanings and implications within the scope of this study; And in Section 5 we conclude with thoughts on the work, objectives, results achieved to date, and the limitations that have influenced this research, ending this article by outlining possible future directions for the research.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Expanded Cinema

Expanded cinema emerged during the post-war period, characterized by a desire for political, social, and artistic revolution – a shift from traditional paradigms during the 1960s and 1970s. According to Gene Youngblood (1970), who coined the term, there was an increasing need for media communication to accompany the progressively more rapid societal changes that humanity was experiencing – and continues to do so. If “[c]hange is now our only constant, a global institution” (Youngblood 1970, 50), it is essential for the social environment experiencing these transformations to evolve alongside these changes. In Youngblood’s view, the popularized media communication of entertainment at the time failed to genuinely provide content capable of fostering human cognitive evolution. The profit-driven motivation of commercial entertainment focused solely on gratifying preconditioned needs through formulaic triggers, such as plot, story, and drama, offering viewers only what they unconsciously anticipated, inherently restricting societal and artistic change. It confirms the pre-existing awareness of consumers, rather than expanding it to truly understand the surrounding environment, how it influences them, and the changes to which they are subjected. Art, existing within the social, technical, and cultural milieu (Frayling 1993), should follow the revolutionary desire of the artist, as it addresses past frustrations stemming from these changes. The artist engages creatively with the repetitive information from commercial media to uncover hidden insights and offer new interpretations. As Youngblood points out, “entertainment gives us what we want; art gives us what we don’t know we want” (1970, 60).

Youngblood proposed a new model of cinema – one that expands the artist, the screen, the film, and the audience. Unlike mainstream entertainment, which often delivers all the details needed for a linear narrative understanding, this approach emphasizes sensory and poetic expression and encourages viewers to form personal and subjective connections with the work, leading to a deeper emotional engagement. Expanded cinema sees its form and content as the same; its films are something, rather than being about something. It exists as an extension of the filmmaker’s nervous system (Youngblood 1970), embraced by the empathy of cognition within the unarticulated consciousness of the viewer. Expanded cinema allowed artists to experiment with new forms of expression, challenging conventional notions of authorship, spectatorship, and exhibition – a perspective on the possibilities of what cinema and film offered through light, shadows, objects, time, and space (Leonard 2013). Moreover, as Sheldon Renan (1967) argued, this type of cinema is expanded to the extent that the effect of the movie or multimedia audiovisual object can be produced without celluloid film, the standard element of the cinematic medium. Youngblood suggests that this abstraction enables the viewer to perceive the whole, rather than fragmenting it into parts, restoring a characteristic typical of the childlike mind – the gestalt-free image association. In 1968, with Auf+Ab+An+Zu (Up+Down+On+Off), artist Valie Export invited her spectators to create the very film they were watching by actively participating in the editing process simultaneously with its projection. Unlike the traditional practice of editing directly on the film strip to be projected, the editing in this work takes place on the projection screen itself, challenging the usual editing process in cinema post-production. The blank projection screen displays a cellulose film strip containing only portions of the movie’s image, while the rest is covered with geometric shapes. The screen eventually becomes marked by the audience, directly representing their perception of the movie and, as an integral element of the work, enriching it with new interpretative possibilities. The film is, consequently, influenced and crafted by its viewers as well.

New interpretations emerge about what defines a screen – the projection window of a film – challenging its limits. In the arts, the window symbolizes a perspective meant to be expressed (Branco 2020). In painting, the edges of the window – the canvas – create a physical boundary between the reality shown and the reality experienced by the viewer. “The framing of the moving image marks a separation between the material surface of the wall and the view contained within the screen” (Branco 2020, 24). Artists working in expanded cinema explore the true line between what’s represented and what’s experienced, questioning the real limits of the window. According to Uroskie (2014), expanded cinema exists in a unique space that bridges traditional darkened cinema and the well-lit settings of museum exhibitions. The question of the limits of the artistic piece thus begins to include its pre-defined exhibition space, and questions arise about the relationship that the artifact and the space share and how they affect each other. Lynn Hershman Leeson uses the window metaphor in the most literal sense, but subverts the expectation of where this window is by projecting images onto actual windows at night to provoke a response from viewers (Dell’Aria and Buchanan 2021). In her work Two Stories Building, she employed twelve projectors to create the illusion of a fire in the San Francisco Academy of Art’s windows in 1979. As the flames flickered, smoke machines released clouds of smoke, and dancers sprang from the windows. The performance was so convincing that it prompted emergency calls to the fire department. By maintaining a straightforward interpretation of the window metaphor, Leeson mixes two distinct realities – the one performed and the one received by the audience. Both of these aspects work together, creating an ecosystem of mutual collaboration that represents the experience.

This type of synergy allows this installation to be considered site-specific and, according to Kaye (2000), “to move the site-specific work is to replace it, to make it something else”. In this case, if Leeson had decided to do the Two Stories Building in any building other than the San Francisco Academy of Art, not only would the qualities of the space be subject to changes that would radically alter the performance, but also her audience would be different. Adapting spaces with cultural and historical significance into artistic settings invites the audience to see what surrounds them truly, fostering new ways of perceiving connections and presences within a space (Dell’Aria and Buchanan 2021).

A ‘site-specific work’ might articulate and define itself through properties, qualities or meanings produced in specific relationships between an ‘object’ or ‘event’ and a position it occupies. (Kaye 2000, 1)

For instance, in 2014, Krzysztof Wodiczko and Gary Kirkham used the Queen Victoria statue in Victoria Park, Kitchener-Waterloo, as a canvas for their projections. The choice of the statue was deliberate, as the images portrayed the experiences of individuals who suffered under colonialism. In Queen Victoria (2014), only the statue’s face and midsection were illuminated at times, with the projections often showing just the face of the speaker, one of whom was shown with their arms cradling a baby. This juxtaposition between the authoritative symbol of the Queen and the diverse, unheard faces and voices she embodied in the projections created a powerful contrast. The artwork challenged habitual relationships with public space, transforming it into a place of resistance, collectivity, collaboration, and connection. It

activates spatiotemporal layers that are more often than not overwritten within the dominant discourses of exhibition space. (MacDonald 2018, 25)

Expanded cinema has transformed from just engaging passive viewers to creating an interactive media landscape (Orciuoli 2022). Digital technologies enable the simulation of space and time, blurring the line between physical and virtual reality (Song et al. 2023), allowing viewers to participate in a virtual world actively. For instance, the film The Witness (2011) was first showcased in a Berlin hotel room for select winners of an online contest. Participants experienced the opening scene via virtual reality on their phones. The narrative follows Nadia, a young Russian prostitute kidnapped and sets players on a city-wide treasure hunt guided by GPS. Through puzzles and decisions, they strive to ensure both Nadia’s survival and their own. As technology continues to evolve, new challenges for expanded cinema emerge. Presenting visuals in virtual or augmented reality makes us rethink what a screen is and how immersive it can be. In Youngblood’s own words, from the preface to the special fiftieth-anniversary edition of his book Expanded Cinema, “reality technologies [VR, AR, MR, XR] are the new expanded cinema.” Orciuoli (2022) notes that achieving photorealism in virtual environments is not the only factor for viewer immersion. Just as books can engage readers without transporting them physically, Murphy (2017) argues that effective VR experiences must evoke interest through emotionally resonant elements. This means that VR should embrace a poetic, aesthetic approach for a truly immersive experience. Immersion can be defined in two ways: as the technology-induced sensation of being immersed in data, and as being captured by a story (Doonan, Oliveira and Ravenelle 2023, 1). Regardless of whether the context is rooted in reality, digital realms, or a combination of both, the aim is to encourage self-reflection and an engaging experience. In 2017, Laurie Anderson and Hsin-Chien Huang created an immersive VR project, Chalkroom, allowing users to roam through a dark space filled with chalk drawings and graffiti that extend into a digital universe in constant metamorphosis. Words and images seem to disintegrate, only to be reborn in a new form, reflecting the fluid nature of human memory. This digital space responds to each viewer’s presence, creating a one-of-a-kind interactive experience.

Federico Biggio, however, argues that

[i]t is very difficult, if not impossible, to precisely mark the point where an augmented reality application ceases to function as a cognitive enhancer and becomes a cultural product for the irrational entertainment produced by the media industry. (Biggio 2022, 187-188)

Biggio identifies three types of artificial gazes that viewers may adopt when consuming cinematic content through mixed reality technologies. The first is the increased gaze, which allows for the superimposition of a virtual world onto the physical, real world. According to Biggio, the most sophisticated technologies of this type employ eye tracking to adapt content based on eye movements, which functions as a cognitive deactivator. Next, he introduces the distant gaze, distinguishing between human and machine-based learning. This distinction highlights the differences in interpreting information’s figurative and cultural meaning, as machine learning focuses solely on a formal and statistical perspective. Finally, Biggio discusses the anesthetized gaze, heavily influenced by personalized algorithms operating through filter bubbles. These algorithms promise to provide viewers only what they know they want, like, and expect. This reinforces the idea that personal preferences are the sole – or most accurate – way to perceive the world.

2.2. Agency

The spectator is no longer seen as a passive viewer of images and sounds; instead, they actively engage, process, interpret, and sometimes even participate in the narrative (Tikka 2004). This engagement assumes an audience willing to embrace the subjectivity and abstraction typical of artistic installations. Spectatorship varies based on individual motivation (Aarseth 1997), the agency a spectator chooses to exercise can impact the work’s narrative structure, presentation, and discourse (Ryan 2005). The spectator is, the, an agent of the work — someone who adopts a performative persona through the artistic experience (Aarseth 1997). Murray (1997, 126) defines agency as the “satisfying power to take meaningful action to see the results of our decisions and choices.” An agent must adapt to the scenario, taking on various roles, some more challenging than others. Nguyen (2020) argues that this adaptability mirrors human existence since we frequently switch between roles, such as parent, professional, and friend, each requiring different states of mind (2020, 27). Unlike real life, however, “[s]truggles in games can be carefully shaped in order to be interesting, fun, or even beautiful to the struggler” (Nguyen 2020, 7). The obstacles in everyday life differ from those in games, as the latter are designed to be solvable, respecting our cognitive limits – “playing a game is the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles” (Suits 1978, 55). In real life, finding harmony between our capabilities and our tasks can be challenging. Nguyen (2020) differentiates between goals and purposes that motivate game players. In the children’s game Red Light, Green Light, the goal is to be the first to reach the opposite side without getting caught moving. While reaching this goal can be thrilling, many players still enjoy the game even if they fail. The goal of reaching the end represents the goal, while the underlying purpose is simply to have fun. Goals stem from the game’s rules, but each player sets their own purpose.

Nguyen identifies two types of gameplay: achievement play, focused on winning, and striving play, which values the challenges. A third type, aesthetic striving play, emphasizes the beauty of overcoming obstacles, aligns with the idea of evocation in expanded cinema, described by Youngblood (1970) as having a poetic and aesthetic nature – the desire of the experience, induced by sensory stimuli. Youngblood contrasts expositional narrative with evocative synaesthesia, stating that the latter creates an experience rather than merely telling a story (Youngblood 1970, 92). Kid A Mnesia (2021) is an interactive digital exhibition showcasing artwork from Radiohead’s albums Kid A (2000) and Amnesiac (2001). As an exploration game, players navigate an abstract virtual museum featuring designs by Thom Yorke and Stanley Donwood, alongside audio from the albums. There are no specific goals, obstacles, or scoring systems; instead, the experience resembles a maze, with all elements equally significant. This simplicity and disorientation have led some to label it a “game that is not a game” (Geller 2023). To grasp the connection between kinaesthetic cinema and aesthetic striving games, we need to examine their differences and how they can coexist (Matt 2021). Recognizing what sets apart and links video games and cinema, especially interactive cinema, is crucial. Both media provide unique experiences that can create connections through shared engagement (Matt 2021).

Understanding the adaptability of information between these forms can help break down barriers while revealing their commonalities (Jenkins 2006). This coexistence reshapes their functions and impacts how messages are received. As Henry Jenkins notes,

[c]onvergence alters the logic by which media industries operate and by which media consumers process news and entertainment” (2006, 15-16)

Adams highlights that

interactivity is almost the opposite of narrative; narrative flows under the author’s direction, while interactivity depends on the player for motive power. (Adams 1999)

In traditional narratives, authors guide the storyline, allowing audiences to consume content passively. In contrast, interactive experiences give players the freedom to navigate their environments through choices, resulting in unpredictable narratives. Recognizing that “if some games tell stories, they are unlikely to tell them in the same ways that other media tell stories” (Jenkins 2004, 120) has led to richer, immersive narratives and broadened the narrative landscape beyond static forms (Koenitz 2014), without negating the existence of each medium as it stands (Matt 2021). Matt highlights the idea that interactivity is crucial in video games, going beyond traditional decision-making. In Oliver Hirschbiegel’s Mörderische Entscheidung (“Murderous Decision”), viewers’ agency does not detract from the narrative – rather, it shapes their understanding of the plot. The film aired on two channels simultaneously, requiring viewers to switch back and forth for a complete experience. This setup created a fear of missing critical scenes, as vital content was dispersed across both broadcasts.

In aesthetically driven gameplay, the game’s goals often take a backseat, just as a linear narrative isn’t the focal point in aesthetic cinema. Kinaesthetic cinema is a powerful means to model human consciousness, mirroring its complexities (Tikka 2004). Damasio (2002) likens film to a “multimedia show,” encapsulating various sensory characteristics. This approach fosters a dialogue between creator and viewer, though personal interpretation remains influenced by subjectivity (Youngblood 1970). Viewers must synthesize distinct pieces of information for a cohesive understanding, reflecting the interplay between individual experience and the collective audience. One example of this is Lis Rhodes’ Light Music (1975). This installation featured a foggy room with two projectors displaying hand-drawn black-and-white lines that Rhodes converted into audio, creating a synchronized soundtrack. However, the experience of the work changes with each exhibition, not in content or presentation, but in how audiences engage with it. As Rhodes noted in a 2012 interview, “In Tokyo, the audience sat down; in Athens, they danced; in Germany, much slower movement” (Rhodes 2012). This interaction directly shapes the collective perception of the piece. The audience thus becomes a collaborative artist, engaging in an improvised performance that emerges from their collective agency.

Marie-Laure Ryan (2005) describes interactivity using the metaphor of an onion. The outer layers affect how the narrative is presented, established before the software runs. As you peel back layers, the interactive agent starts to understand their role, though core elements are still predetermined. Choices may lead to different paths, but these outcomes are pre-programmed. In the innermost layers, the narrative evolves dynamically through user-system interaction. Ryan also introduces meta-interactivity, where the focus shifts from a specific layer to the whole onion. At this level, the interactor shifts from merely consuming the narrative to creating new experiences for others. However, Ryan notes that

the two roles do not merge, since users cannot simultaneously immerse themselves in a story world and write the code that brings this world to life (Ryan 2005)

Taking responsibility for artwork may lead viewers to reconsider the roles among the artist, the audience, and the artwork. Questions arise such as:

Where, and what am ‘I’? Am I the sender or the receiver? I am certainly part of the medium, so perhaps I am the message (Aarseth 1997, 162)

An author controls their work, possessing “configurative power” over it (Aarseth 1997). Thus, it’s not merely interactivity that grants co-author status, but the ability to reshape the original work beyond the creator’s vision (Aarseth 1997). Ilya Kabakov, in an interview with Emilia for TateShots, explains that an artist incorporates life experiences into their art, but adds, “The viewer, however much they wish to, cannot totally see the work in its complexity with all its details” (Kabakov 2017). He notes that the aim of his work isn’t for the viewer to decipher his exact intentions, but to feel the metaphor in their own language. The artist and viewer communicate in distinct ways. Although the hierarchical relationship between them may not be overt, “then the real artist must be hiding somewhere” (Aarseth 1997, 165). This relationship is shaped by the power dynamics each participant can exert. Foucault (1980) posits that power is a productive network throughout society, and Wilson and Sicart assert that “power is only productive in dialogue” (2010, 6).

2.3. Darkplay

Wilson and Sicart (2010) define abusive game design as a means to foster interaction between game designers and players, enhancing the personal nature of gaming. This design intentionally challenges the norms that typically ensure player enjoyment and engagement. Importantly, “abusive” does not imply random cruelty; rather, it emphasizes the human elements in gameplay, focusing on both players and designers. The role of the abusive game designer is to skillfully push players to their limits without breaking their spirit. Maintaining a positive discomfort (Mortensen and Jørgensen 2020) is essential between the imposed challenges and player motivations; as Wilson and Sicart (2010, 7) argue, “you can’t abuse your players if they stop playing your game.” Furthermore, distinguishing between purpose and goal in gaming (Nguyen 2020) is crucial, as players need to believe they can achieve their objectives to retain their lusory attitude (Suits 1978). Zvan and Schifter (2022) mention that the perception of abuse varies by cultural context, affecting how players perceive their experiences. For this research, we will specifically examine darkplay, described as “when the game plays the player” (Mortensen, Linderloth and Brown 2015, 4). The term “darkplay” comes from performance arts and refers to situations where not all participants are aware of their involvement in potentially playful activities (Schechner 2002). It creates a mysterious atmosphere by obscuring the game’s rules, subverting players’ expectations, and prompting them to explore unknown limits. This leads to a range of outcomes: players may find clarity or become more confused as they base decisions on incomplete information. A prime example is in Papers, Please (2013), where players act as immigration inspectors in Arstotzka. As they verify documents of those crossing from Kolechia, the game’s rules unfold gradually. Players must balance earning credits for their families while confronting the moral weight of their choices: Are the documents valid? Is someone lying? Does granting passage ensure a better future? As the game progresses, the pressure mounts – one day may not provide enough resources, and the criteria for decisions become increasingly complex. Each encounter prompts reflection, making this game less about enjoyment and more about the heavy responsibility that comes with the role. Yet, this uncertainty compels players to keep engaging with it.

Wilson and Sicart (2010) argue that while conservative game designers create tools aimed at predictable player enjoyment, abusive game designers exploit game mechanics as a means of power, undermining centralized gaming experiences. New methods arise as a reaction against traditional norms. Similar to expanded cinema, these designers challenge the profit-driven philosophies of mainstream entertainment, which reinforce rather than expand consciousness (Youngblood 1970). Both concepts possess a revolutionary essence, aiming to reveal deeper insights about the human mind shaped by the choices of its agents. In the realm of expanded cinema, dark play emphasizes the viewer’s engagement with the artistic work, revealing their limited understanding of its context. This goes beyond mere technique; it transforms the entire piece, prompting exploration and comprehension. Youngblood captures this notion, stating,

[m]an does not comprehend his relationship to the universe... He insists on ‘doing his thing’ without the slightest notion of what his ‘thing’ might be. (Youngblood 1970, 53)

In everyday life, people often lack awareness of the implications of their actions, which might not prevent them from acting. In limited contexts, discovering the unseen can encourage rule-breaking, as it tends not to affect their lives beyond that specific situation. Darkplay immerses viewers in the action, breaking their pre-established roles. It highlights a hierarchy between the artist and the audience, as only the creator fully grasps the work’s universe. By engaging with it, viewers embrace their curiosity. Here, the “dark” aspect refers to the unknown elements, while “play” signifies the process of discovery. This interaction evokes a childlike spirit:

To play is to be in the world. Playing is a form of understanding what surrounds us and who we are, and a way of engaging with others. Play is a mode of being human. (Sicart 2017, 1)

In the context of expanded cinema, darkplay acts as a metaphor for the universal human experience, fostering direct dialogue between the artist and the audience. It broadens the screen, extending beyond projection to include the metaphysical, revealing various levels of knowledge and types of agency. Ultimately, it expands the viewer’s cognitive language, inviting them to explore an entirely unfamiliar universe driven by curiosity.

3. Methodology

This research follows an Art-Based Research (ABR) methodology, facing the systematic use of artistic and design procedures (McNiff 2007). ABR is commonly concerned with different problems compared to research in the sciences, employing different approaches and methods when finding a solution to a problem (Cross 2006). In scientific research, validity is established through repeated experiments – replicable phenomena represent universal truths. On the other hand, ABR operates through the repetition of the phenomenon with differences in its core, where the “truthfulness” of that phenomenon lies in the impact that it represents in the social world (Bolt 2016) since the replicability of this desired impact would only be redundant, not focused on adding new knowledge and would only validate already existent ones. Arts and Design usually focus on ill-defined problems (Cross 2006) where not all the information is given clearly to the artist, opening space for the researcher’s tacit knowledge to facilitate a wide range of possible and satisfying solutions to that specific problem. At their essence, both science and art delve into the unknown, conducting experiments to enhance understanding. However, their motivations differ (Galdon and Hall 2022). In science, pinpointing the research problem helps scientists focus their efforts; in contrast, artists often lack clear answers initially, with insights emerging as their work evolves. The artist then takes a performative position in the context of the problem, with performative research being constructed as practice-led research since it “is intrinsically experiential and comes to the fore when the researcher creates new artistic forms for performance and exhibition” (Haseman 2006). This practical orientation of the research originates from a scenario where the resultant art “is both productive in its own right as well as being data that could be analyzed using qualitative and aesthetic modes” (Bolt 2016). The artifact embodies the researcher’s analytic and expressive cognitive idiom, transposed in explicit and implicit knowledge (Frayling 1993). However, artifacts are not only representations of knowledge, but also enhancements of new understandings, both explicit and implicit. The artistic and creative process is highly subjective, unique, and personal to the artist producing it, often hard to put into words. This issue with verbalizing the tacit knowledge creates the emerging necessity for a unique lexicon and syntax to handle ideas of the cognitive process (Archer, 1980) inside an artist’s mind. As Nigel Cross tells us,

[t]here are things to know, ways of knowing them, and ways of finding out about them that are specific to the design area (Cross 2006, 5)

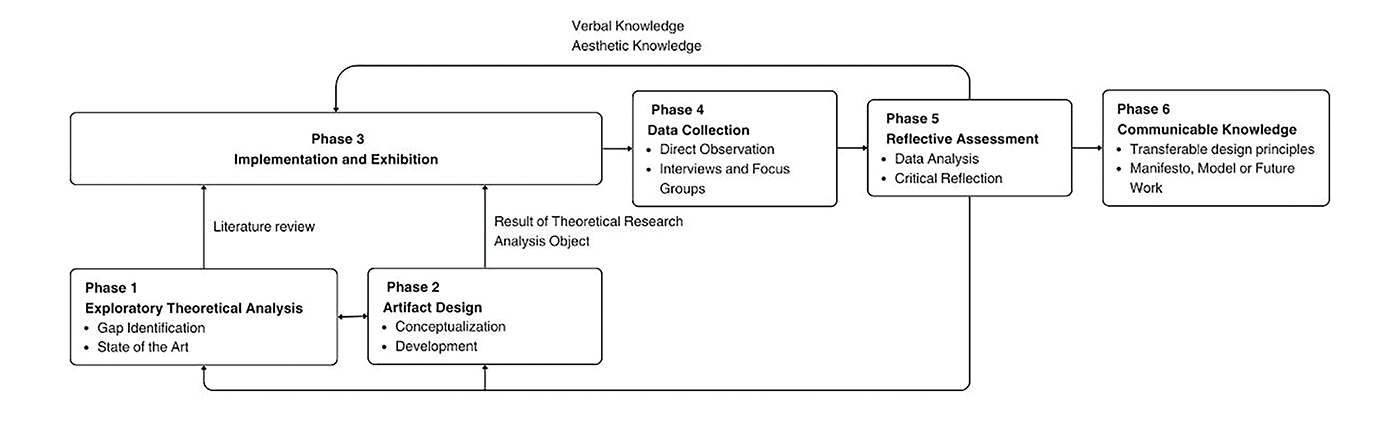

Figure 1 shows the overall research process, which is divided into 6 phases, which help to structure and guide the study. The first two phases occurred simultaneously and both affect the third, and current, phase of the research. The remaining 3 phases follow, which occur in a more linear manner precisely because of the dependent relationship that the phases have with each other. Nevertheless, it will be possible to revisit past phases, enriching them with new knowledge acquired in future phases.

3.1. Phases 1, 2 and 3

The research, as shown in Figure 1, began with a theoretical exploration of key topics. This included analyzing academic and informational articles, books, grey literature, and a collection of relevant artifacts to define the state of the art. The gathered content was categorized as central, tangential, or less relevant but kept for future reference. This literature review established a solid theoretical foundation for the concepts and highlighted existing research gaps. This initial phase sets the stage for artifact design (Phase 2), which overlaps with Phase 1. Insights gained here inform the conceptual development of the artifacts, leading to specific questions for exploration by artists and researchers. Prototypes are developed through graphical representation and experimentation with materials and techniques to ensure they achieve their intended aesthetic, conceptual, and functional goals. Phase 3 focuses on implementing the artifacts in real-world settings. The expanded cinema artifacts will be exhibited in designated spaces, where participants will engage as both audience members and active contributors to the artistic experience.

3.2. Phase 4

Phase 4 will function simultaneously with Phase 3, to collect data, particularly through field-based data collection techniques, such as semi-structured direct observation at the exhibition site, complemented by photographs and videos that will serve as visual support for the data collected for subsequent analysis. Additionally, anonymous semi-structured interviews will be conducted with participants after they visit the artifact exhibition.

| Technique | Why? | How? | When? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semi Structured Direct Observation |

To understand the relationship established between the audience, the space, and the artifact |

Photography Video Observation Grid |

During the exhibitions |

|

Semi Structured Interviews |

To examine the audience’s perceptions of the work and their perceived sense of agency |

Audio Recording Audio Notes Interview Script |

Right after the exhibitions |

3.2.1. Semi-Structured Direct Observation

Direct observation will assess the relationship between the audience, the space, and the artifact to determine if the objectives were met. The data to be collected will specifically relate to the conceptualization, design, implementation, and exhibition of the artifacts, assessing:

- A. The apparent willingness to interact with these artifacts;

- B. The agency, whether conscious or unconscious, of the audience.

To this end, direct observation will follow an observation grid that will focus on the following areas:

- A. Positioning within the exhibition space;

- B. Movement through the exhibition space;

- C. Physical proximity between the viewer and the artifact;

- D. Interaction attempts:

- a. Pre-planned actions that directly produce effects;

- b. Unexpected actions that result in an outcome;

- c. Unexpected actions that have no influence;

- E. Circulation speed;

- F. Duration of stay in the space;

- G. Points of attention;

- H. Practical difficulties encountered by the audience;

- I. Possible technical issues in the functional aspects of the artifacts.

3.2.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

The interviews will also be conducted in the context of the exhibitions, taking place as viewers exit, with their anonymity guaranteed. The interviews will examine the audience’s perceptions of the work and their perceived sense of agency concerning it. Thus, the data collected aligns with the goals related to the conceptualization, design, implementation, and exhibition of the artifacts. The interviews will address the following aspects:

- A. The agent’s actual willingness to interact with the artifact;

- B. The real interaction with the artifact;

- C. The difficulties encountered by the agent;

- D. The awareness and sense of responsibility derived from the feeling of agency.

Upon concluding their visit to the exhibition, participants will be invited to engage in a brief dialogue about their experience at the exhibition. During the interview, the viewer will have the opportunity to discuss their viewing and interaction experience with the work, being guided by the interviewer to reflect on their sense of agency, specifically:

- A. Whether this sense of agency was felt;

- B. When it was experienced;

- C. What triggered it;

- D. Which actions were considered;

- E. Which actions were taken;

- F. What consequences of those actions did the viewer become aware of.

3.3. Phases 5 and 6

After collecting data, we move to Phase 5, which focuses on analysis and interpretation. Two strategies are employed for processing the data gathered from semi-structured observations and interviews. First, transcribe the data quickly to facilitate analysis without relying on audio, video, or photographs from the exhibitions. Make sure to annotate the transcriptions to provide context, allowing for the disposal of supplementary materials. For analysis, direct observation data will undergo trend analysis, while interview data will be examined through thematic analysis. Once both analyses are complete, we will critically and reflectively analyze the results concerning our research interests.

3.3.1. Trend Analysis

Trend analysis will be applied to data obtained from semi-structured direct observation. After completing the observation grid, the data will be visually represented using bar charts to aid in identifying patterns. Subsequently, apparent relationships between these trends within categories will be explored, focusing on:

- A. Temporal issues:

- a. Visit duration;

- b. Circulation speed;

- c. Length of stay;

- B. Spatial issues:

- a. Proximity established to the artifact;

- b. Physical interaction with the artifact;

- C. Agency.

To achieve this, contextual tendencies associated with each trend will also need to be considered. This process will involve contextualization, supported by the creation of Venn diagrams, which will allow for a clearer visual representation of these relationships.

3.3.2. Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis will be the strategy applied to the data obtained from the semi-structured interviews. The interview script was designed to guide the discussion toward specific themes and sub-themes, namely:

- A. Agency:

- a. Will to interact;

- b. Sense of agency;

- B. Darkplay:

- a. Interactions’ outcome;

- b. Unfolding the universe.

Nonetheless, new themes and sub-themes may emerge during the analysis process. The transcription will be fragmented to associate codes with each theme. Subsequently, a report will be developed based on the codes (excerpts from the transcriptions) describing the results obtained for each theme.

This process enhances both verbal and aesthetic knowledge, allowing for potential revisions in implementation. At this point, decisions may arise to modify existing artifacts or create new ones. The outcomes of Phase 5 support Phase 6, translating into communicable knowledge of transferable principles. Here, synthesizing the collected information can take the form of conceptual or theoretical models, a manifesto, or a plan for future work. The articulation of this knowledge will depend on its characteristics, ensuring the adaptation aligns with its nature.

3.4. Participants

To simplify participant recruitment, this study uses convenience sampling for data collection methods, including semi-structured direct observation and interviews. The sample will consist of random attendees from the exhibitions held during the research. This strategy saves time and resources while enhancing the quality of insights gathered, aligning with the study’s goals. The sample will not have strict sociodemographic limitations but will match the target audience of the installations and artifacts. It will include individuals interested in artistic exhibition spaces, whether as consumers or creators. Participation will be anonymous, as identifying individuals does not add significant value to the study.

4. Artworks

The paper proceeds to examine the two artifacts set for development: “Stationary Childhood Museum,” an interactive video installation – described in Section 4.1 –, and “Glimpses of Serenity,” a virtual reality experience – detailed in Section 4.2. Each artifact will be situated within a conceptual framework that drives its creation. Additionally, the paper will outline the overall artifact motivation, the interaction mechanics, required materials, and the darkplay universe relevant to the work.

4.1. “Stationary Childhood Museum”

The “Stationary Childhood Museum” is a video installation intended for a theatre setting, grounded in the notion of the passive spectator – not only the traditional audience members who occupy this space, but also those who observe their own lives without fully recognizing their presence and its impact on their surroundings. This film draws on video footage from the first author’s childhood, highlighting both ordinary moments and those of greater significance, the dates of which lend context to these experiences. It explores the roles we embody in our lives, both in the present and when reflecting on the past, raising questions about how we influence and interact with the world around us. The audience is invited to take a seat and observe the unfolding events. Initially, the audience appears passive, and the installation seems to center on an intentional agent. However, the moment one person chooses to sit down, this simple action begins to influence the dynamics of the installation. The spectator may or may not realize this connection; if they become curious, they might engage with it further by observing closely or through experimentation. Consequently, each person’s experience will be distinct, regardless of whether they understand the impact of their actions on the work at any given time.

4.1.1. Agency Mechanics

At the outset, two potential interaction mechanisms were identified: a) buttons integrated into the theater seats, which capture the act of sitting, and b) a computer vision system capable of not only detecting this action (by identifying a sudden change in person’s height) but also analyzing the positions and closeness of attendees within the theater. For the button approach, the design involves incorporating push buttons, 1N4148 diodes, Arduino Mega, and pull-down resistors. This system features a matrix containing all the buttons. Whenever any of these buttons or combinations thereof are pressed, the resulting action influences the dynamics of the installation, thereby affecting the film’s narrative, aesthetic presentation, and other elements that contribute to the overall atmosphere. Conversely, the computer vision method employs software for the detection of individuals and their facial expressions, allowing for the analysis of images similarly to the button matrix, but tailored for this specific context. In this setup, when a person sits down, stands up, or remains standing, regardless of their engagement with the film or their seating preferences, they exert their agency. Such actions would function as input, resulting in outputs that would impact the installation experience. The proposed model will adopt a mixed approach that integrates various solutions. This method minimizes the need for multiple controls and reduces the amount of material required to cover an entire theater room. Furthermore, it enables computer vision to concentrate on specific sections of the room and interpret different types of audience presence through body language. These observations will lead to modifications in the installation, which will vary based on the audience size and the film’s duration. The resulting outputs will manifest as changes in narrative and aesthetics, potentially altering the structure of the narrative in real-time or influencing elements such as visual content, spoken and narrated dialogue, film projection, and the overall ambiance of the theater.

4.1.2. Darkplay

As discussed in section 4.1.1 (Agency Mechanics), the simple act of sitting down to watch a film transforms the spectator into an active participant in the work. Once a spectator begins to comprehend, or believes they understand, the workings of the universe presented in the film, their actions as a participant become less predictable, as do the consequences of those actions. They may feel compelled to explore the boundaries of this universe, seeking to grasp its patterns and the implications of their experiences. Additionally, they might recognize that the installation responds to their presence, though they may choose not to pursue a deeper understanding of this interaction, or they might remain unaware of this connection altogether. Let’s picture this scenario: A person strolls into a theater, still flipping through the schedule, and suddenly realizes a film is playing. They settle into a seat and start paying attention. Just then, without them realizing it, the film unexpectedly jumps to a completely different memory. At that moment, another audience member sits down, causing a five-second pause in the video. This brief interruption could be a tad confusing for both viewers. The former might think it’s a glitch, or if the timing aligns just right, they might perceive it as a meaningful pause. The latter might just wonder why things suddenly went silent, especially since it coincided with their arrival. Now, if a third person joins the audience and causes the main lights in the theater to flicker on for a few seconds, it would only add to the strangeness. Even if the film continues to roll, the sudden brightness could be jarring, particularly for the new arrival, who might quickly jump to a different seat, worried that the one they just occupied could be “faulty.” Meanwhile, another viewer skeptical of these odd occurrences could see it as evidence of a deeper conspiracy, while a technical-minded viewer might begin to suspect the crew behind the scenes.

4.1.3. Development

I began by compiling the foundational material for the film, consisting of 16 Mini-DVD cassettes recorded between 2004 and 2008, capturing my development from ages 2 to 6. Among these cassettes, 10 are primarily focused on me, while 3 document a family trip, 2 capture a ballet performance in its entirety, and the final one celebrates the birth of my sister and her integration into our family.

To preserve the original recordings and facilitate editing, all cassettes underwent a digitalization process. Currently, I am engaged in analyzing, selecting, and cutting excerpts, categorizing them into 10 different themes such as “games,” “singing,” and “relatives.” Each video is linked to one or more categories, resulting in a network of connections. The next step involves film editing, which will consider the potential variations arising from the interaction matrix. This editing may result in a linear sequence with branching narratives, or it may deviate from conventional linear storytelling. Given that expanded cinema is a synesthetic experience (as noted by Youngblood, 1970), the logical connections emerging from the content will largely depend on the individual viewer’s experiences and interpretations. Additionally, it will be essential to prototype the interaction mechanisms at both practical and functional levels. Ultimately, the “Stationary Childhood Museum” will be presented, which will help illuminate the relationships that visitors establish with the work.

4.2. “Glimpses of Serenity”

The second artifact in development, entitled “Glimpses of Serenity,” presents a virtual reality experience that starts within an infinite expanse of white space. As the user blinks, the environment gradually takes form, revealing the interior of an unoccupied house. Users can navigate this space, which adjusts based on their position within the virtual realm. At specific viewpoints, videos, photographs, and drawings that evoke memories associated with those areas are superimposed onto the scene.

This design aligns with the concept of innocent agency, utilizing blinking – an involuntary action that users cannot control – as a mechanism for memory retrieval. The artifact effectively simulates the unpredictable manner in which memories surface in our consciousness.

4.1.1. Mechanics

To address the requirements of the project, the initial stage involves employing 3D Gaussian Splatting to develop a digital environment that can be transformed into a virtual reality (VR) space for unrestricted exploration. The Oculus Quest Pro will serve as the primary device, leveraging its eye-tracking capabilities to monitor eye blinks. This functionality will enable the environment to gradually take shape, layering in memories as the user navigates through the space. It is essential to understand that the construction of this environment depends significantly on the agent’s location. As the agent draws closer, the environment begins to materialize, and this process accelerates with each blink. This concept suggests that elements that initially appeared to form slowly can suddenly become fully visible in the blink of an eye. Once established, the environment remains intact even as the agent moves away, maintaining its structure. Conversely, the emergence of memories within the space, while based on similar principles, is contingent not only on their spatial arrangement and the act of blinking but also on the user’s head and eye movements. Additionally, these memories will not be permanently fixed in the environment. Their visibility is transient and influenced by where the agent directs their attention. For instance, a glance or blink toward a different part of the room can cause a memory to disappear. Many other memories await discovery, and no barriers are preventing the viewer from re-triggering these memories later in the experience.

4.1.2. Darkplay

In “Glimpses of Serenity,” unintentional interaction is explored through a fundamental biological action: blinking. This is a completely instinctive behavior for humans, a subconscious action, regulated by our autonomic nervous system. While various factors contribute to the interactions within the system, blinking emerges as the most unpredictable element, affecting both the outcomes and the agents involved, who merely blink their eyes without conscious effort. Over time, agents that actively engage with the rules of the virtual reality experience may start to recognize how their blinking impacts the system, leading them to experiment with this action intentionally. However, this deliberate effort cannot completely prevent them from blinking instinctively at any moment, underscoring the dual nature of this natural response.

5. Conclusion and Future Work

As research continues, we will collect more data and insights that will enhance our understanding of the study’s results. Nevertheless, it’s essential to reflect on the outcomes already achieved, while also considering the limitations faced during the process. Although expanded cinema originated in an analogue context with distinct production, exhibition, and consumption practices compared to today’s cinematic landscape, we recognize that even in the digital age, it is feasible to create cinematic experiences that transcend traditional boundaries. By embracing the multidisciplinary nature of expanded cinema, we can connect it to concepts from game design, particularly agency and darkplay. In this regard, darkplay, influenced by the viewers’ agency, stands out as a key factor highlighting the need for viewers to engage in critical reflection to comprehend the work. This aligns with Youngblood’s (1970) aspiration to broaden the human mind. The study is currently in the development phase for the artifacts, preparing them for exhibition. Most of the limitations encountered during this study are closely tied to this phase, particularly regarding the accessibility of materials and the necessary knowledge to utilize various software applications. Despite these challenges, efforts have consistently been made to find alternatives that address these limitations. The development of the artifacts is nearing completion, positioning them for public exhibition. Although two artifacts have been selected, the conceptualization process generated numerous other ideas. It is important to note that even if these additional concepts are not pursued within the current research framework, they will not be dismissed as potential future projects.

Notes

1Maria Canas, mariacardoso@ua.pt

2Pedro Cardoso, pcardoso@fba.up.pt

3Sérgio Eliseu, s.eliseu@ua.pt

References

Aarseth, Espen J. 1997. Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Baltimore (Md): Johns Hopkins University Press.

Adams, Ernest. 1999. Review of Three Problems for Interactive Storytellers. Gamasutra. December 29, 1999. http://www.designersnotebook.com/Columns/026_Three_Problems/026_three_problems.htm.

Amnesiac. 2001. By Radiohead. Music Album.

Auf+Ab+An+Zu. 1968. By Valie Export. Video Installation.

Biggio, Federico. 2020. “Augmented Consciousness: Artificial Gazes Fifty Years after Gene Youngblood’s Expanded Cinema.” DOAJ (DOAJ: Directory of Open Access Journals), July. https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14329.

Bolt, Barbara. 2016. Review of Artistic Research: A Performative Paradigm. Parse Journal, no. 3.

Branco, Sara Castelo. 2020. “Between the Screen-Sediment and the Shattered Window: The Deconstruction of the Screens Limits and Frames in Moving Image Installations.” Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts 12 (2): 20–36. https://doi.org/10.34632/jsta.2020.8527.

Cross, Nigel. 2006. Designerly Ways of Knowing. Springer London Ltd.

Chalkroom. 2017. By Laurie Anderson and Hsin-Chien Huang. VR Installation.

Damasio, Antonio R. 1999. “How the Brain Creates the Mind.” Scientific American 281 (6): 112–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican1299-112.

Dell’Aria, Annie, and Andy Buchanan. 2021. “Enchanted Encounters: Moving Images, Public Art and an Ethical Sense of Place.” Architecture_MPS 20 (1). https://doi.org/10.14324/111.444.amps.2021v20i1.002.

Doonan, Natalie, Luana Caroline Oliveira, and Christopher Ravenelle. 2023. “Expanding the Magic Circle: Immersive Storytelling That Trains Environmental Perception.” Convergence, July. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565231178917.

Foucault, Michel. 1980. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977. Edited by Colin Gordon. New York: Pantheon Books.

Frayling, Christopher. 1993. Research in Art and Design. Vol. 1. London: Royal College of Art.

Galdon, Fernando, and Ashley Hall. 2022. “(Un)Frayling Design Research in Design Education for the 21Cth.” The Design Journal 25 (6): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2022.2112861.

Geller, Jacob. 2023. Review of Games That Aren’t Games. June 9, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DliX_YFiSX4.

Haseman, Brad. 2006. “A Manifesto for Performative Research.” Media International Australia Incorporating Culture and Policy 118 (1): 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878x0611800113.

I Wanna Be The Guy. 2007. By Michael O’Reily. Videogame.

Jenkins, Henry. 2004. “Game Design as Narrative Architecture.” Web.mit.edu. 2004. https://web.mit.edu/~21fms/People/henry3/games&narrative.html.

Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press.

Kabakov, Ilya, and Emilia Kabakov. n.d. Review of Ilya and Emilia Kabakov – “The Viewer Is the Same as the Artist.” TateShots. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LzrM9v26SPI.

Kaye, Nick. 2000. Site-Specific Art: Performance, Place, and Documentation. London; New York: Routledge.

Kid A. 2000. By Radiohead. Music Album.

Kid A Mnesia. 2021. By Epic Games. Videogame.

Koenitz, Hartmut. 2014. “Five Theses for Interactive Digital Narrative.” Lecture Notes in Computer Science, January, 134–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12337-0_13.

Leonard, Jamie. 2013. “The Changing Perceptions and Interpretations of Expanded Cinema in Relation to Its Contexts and Environments.” Academia.edu. March 25, 2013. https://www.academia.edu/3102152/The_changing_perceptions_and_interpretations_of_expanded_cinema_in_relation_to_its_contexts_and_environments.

Light Music. 1975. Lis Rhodes. Light Installation.

MacDonald, Shana. 2018. “Reimagining Public Space in Expanded Cinema Exhibition.” Canadian Journal of Film Studies 27 (1): 16–30. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjfs.27.1.2017-0012.

Matt, Lily. 2021. “Video Games and Film: Understanding Interactive Cinema.” Uw.pressbooks.pub, July. https://uw.pressbooks.pub/cat2/chapter/video-games-and-film-understanding-interactive-cinema/.

McNiff, Shaun. 1998. Art-Based Research.

Mörderische Entscheidung. 1991. By Hirschbiegel, Oliver. TV Movie.

Mortensen, Torill Elvira, Jonas Linderoth, and Ashley M L Brown. 2015. The Dark Side of Game Play: Controversial Issues in Playful Environments. New York: Routledge.

Mortensen, Torill Elvira, and Kristine Jørgensen. 2020. The Paradox of Transgression in Games. Routledge.

Murphy, Dooley. 2017. Review of Virtual Reality Is “Finally Here”: A Qualitative Exploration of Formal Determinants of Player Experience in VR. Digital Games Research Association. 2017.

Murray, Janet Horowitz. (1997) 2016. Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. Cambridge, MA; London: The MIT Press.

Nguyen, C. Thi. 2020. Games: Agency as Art. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190052089.001.0001.

Orciuoli, Maria. 2022. “Interactivity & Immersivity in Filmic Spaces.” October 20, 2022. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.34534.74565.

Papers, Please. 2013. By Lucas Pope. Videogame.

Queen Victoria. 2014. Krzysztof Wodiczko and Gary Kirkham. Victoria Park, Kitchener-Waterloo. Site-specific Installation.

Renan, Sheldon. 1967. An Introduction to the American Underground Film.

Rhodes, Lis. 2012. Review of Lis Rhodes – “An Opposition to Commercial Cinema.” The Tanks. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ts5uT0Pdj4c.

Ryan, Marie-Laure. 2005. Review of Peeling the Onion: Layers of Interactivity in Digital Narrative Texts. May 2005. http://www.marilaur.info/onion.htm.

Schechner, Richard. 2002. Performance Studies: An Introduction. S.L.: Routledge.

Sicart, Miguel. 2014. Play Matters. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Mit Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10042.001.0001.

Song, Junrong, Bingyuan Wang, Zeyu Wang, and David Kei-Man Yip. 2023. “From Expanded Cinema to Extended Reality: How AI Can Expand and Extend Cinematic Experiences,” September. https://doi.org/10.1145/3615522.3615556.

Suits, Bernard Herbert, Frank Newfeld, and William Rueter. 1978. The Grasshopper Games, Life and Utopia. Toronto [U.A.] University Of Toronto Press.

The Witness. 2011. By 13th Street Universal. Berlin, Germany. AR Movie.

Tikka, Pia. 2004. “(Interactive) Cinema as a Model of Mind.” Digital Creativity 15 (1): 14–17. https://doi.org/10.1076/digc.15.1.14.28151.

Two Stories Building. 1979. By Lynn Hershman Leeson. San Francisco Academy of Art. Site-Specific Performative Installation.

Uroskie, Andrew V. 2014. Between the Black Box and the White Cube: Expanded Cinema and Postwar Art. Chicago; London: University Of Chicago Press.

Wilson, Douglas, and Miguel Sicart. 2010. “Now It’s Personal.” Proceedings of the International Academic Conference on the Future of Game Design and Technology - Futureplay’10. https://doi.org/10.1145/1920778.1920785.

Youngblood, Gene. 1970. Expanded Cinema. New York: Dutton.

Zvan, Brin, and Mathias Schifter. 2022. “There Is No Abusive Game Design: A Typology of Counter Game Design.” https://schifter.dev/documents/Abusive_Game_Design_Thesis.pdf.