Abstract

Through the lens of “econarratives” (Stibbe, 2023), this paper explores The Anthropocene Project, a multi-platform work by Jennifer Baichwal, Edward Burtynsky and Nicholas de Pencier, as it engages with the environmental crises of the Anthropocene. It emphasizes the project’s role in fostering a deeper understanding of interconnectedness between humanity and the world around us. Combining film, photography, interactive and cinematic VR forms, exhibition, and a book, the project offers a rich, immersive experience that challenges traditional storytelling formats, urging viewers to engage with the Earth’s changing realities in more embodied, immersive ways. Drawing on Anna Tsing’s “arts of noticing,” as a radical, and disruptive method for observing the details of the natural world and human intervention, this paper examines how The Anthropocene Project encourages viewers to “notice” the subtle and stark manifestations of human impact on ecosystems. Through its striking visuals and interactive elements, the project invites audiences into an immersive awareness, where the act of noticing becomes an integral part of the larger discourse on the Anthropocene. We propose an exploration on how The Anthropocene Project creates “econarratives” by linking ecological concerns with stories of social justice, sustainability, and interconnectedness. By examining its ability to create a narrative across various media platforms, this paper considers whether, and how, such cinematic and multimedia endeavours, influence public discourse, encourage reflection on the ethical dimensions of ecological destruction, and catalyse a rethinking of prevalent cultural, social and economic values, as well as our relationship with other species and our environment.

Keywords: The Anthropocene Project, Visual Storytelling, Multimedia, Econarratives, Arts of Noticing.

Ecology and the arts in the Anthropocene

Cinema is an important social and political arena for understanding the 20th and 21st centuries. Parallel to aesthetic issues – or perhaps because of them – cinema, through its narratives, constitutes a vehicle for critical reflection on many of the problems of our time. Ecological issues are some of these problems that have been extensively mapped, whether at a strictly scientific level or through artistic practices and/or critical references, particularly in the case of cinema. As we identified in the Project that we recently developed, and in the process of being implemented, in 1966, Roger Anderson made a brief but deeply symptomatic reference to a practice he called ecocinema in a text entitled “Ecocinema. A Plan for Preserving Nature,” arguing that: “The motion pictures should be shown in certain special theaters (I [he] propose[d] they be called Ecocinemas) in which all the appropriate sights, sounds, and smells would be brought together, refined, and improved to produce a form vastly superior to nature itself.” Here, the word ecocinema seemed to point to a physical space (e.g. special cinema rooms as “special theaters”), in an ambiguous sense that the text does not clarify – however, we cannot help but notice that a scientist was already enunciating the potential of cinema to aggregate the multiple, fragmented and subjective perceptions of reality, through an art that artists and critics had already defended as “total” (Canudo, 1911; Dulac, 1927), perhaps in defiance of ideas prior to cinema itself (Wagner, 1850), and challenging Bazin`s doubts who says that “The cinema owes virtually nothing to the scientific spirit.” Despite the debate between realists and Gestalt psychologists – they had already their arenas – the challenge is not so much about reconfiguring theories but about advancing a little further in understanding the processes of perception and agency of a cinema committed to the questions of the representation of ecology and reality, questioning how econarratives in film, supported by knowledge from the humanities, sciences and arts, can constitute a global map of the problems of sustainability, resistance and survival of life on earth.

One of the pressing issues we face, and which urgently warrants our attention, is the question of ecological awareness. The Anthropocene as a concept, broadly defined by scientists as the current geological epoch predominately shaped by human activity, is but one of the examples this concern is currently being addressed. Beyond igniting discussions in geology and earth sciences, anthropology, or international relations, we will argue that it increasingly demands new modes of understanding, expression, and storytelling, in order to capture the scale, complexity, and emotional resonance of the ecological turmoil we face.

In this context, it is precisely the concept of econarrative, as recently employed by Arran Stibbe, that could offer a valuable framework for exploring how stories help shape awareness and make sense of environmental degradation and foster ecological literacy, and reflection. And since perception is linked to the forms of the film, that is, to its aesthetic and creative dimension, creating worldscapes is always about imagining the present and the future.

Imagining our possible futures, the issue of ecology is one of the recurring themes in all cinematographic genres, from drama to comedy; between documentary and fiction, animation and, more recently, interactive documentary. In this presupposition, we seek to understand the narrative in the film The Anthropecene Project, based on the concept of econarrative as described by Arran Stibbe:

[…] why add the prefix ‘eco’ to narrative, and how does the resultant term, ‘econarrative’, differ from just plain ‘narrative’? The prefix ‘eco’ is, of course, an abbreviation of ‘ecology’, a term coined in 1866 by Ernst Haeckel that refers to the interaction of organisms with other organisms and the physical environment. (Stibbe 2024, 29).

In fact, the relationship between cinema and ecology is not limited to the evidence of utopian or dystopian narratives about the ecological future of the Earth and humanity – as we can see in one of the most recent collective studies edited by Katarzyna Paszkiewicz and Andrea Ruthven –, but assumes a peculiar intervention in socio-cultural and political processes, at a global level. The ecological problem in cinema is mapped by several authors who address themes as diverse as colonization, gender issues, globalization, pedagogy and education, ecological practices enhanced by projects, etc. In a chapter entitled “Between Manipulation and Catharsis. Living a Life in the Mediated Anthropocene”, Ignacio Bergillos even revisits Peter Weir’s iconic film, The Truman Show (USA, 1998), to argue for the urgency of a study of the media focused on the dynamics between environmental and social processes, based on themes that are currently at the top of international political agendas: “nature/cultures (Haraway), media/natures (Parikk), geomedia (Fast), technosphere (Haff), technocene (Cera), mediacene (Gurevich), etc.” (Aparício 2024, 218). Bergillos invokes the concept of “technological constellation”, asking about the impact of the intensive use of technologies on the planetary ecosystem. Said briefly and directly: “our love of media and media technology has become part and parcel of our global environmental crisis.” (Stephen Rust, Salma Monani and Sean Cubitt 2015, 1). In parallel, other studies were aggregated in the book Modern Ecopoetry. Reading the Palimpsest of the More-Than-Human World (2021) – edited by Leonor María Martínez Serrano and Cristina M. Gámez-Fernández – highlights the importance of poetry in the process of raising awareness and sensitization to deep ecological issues in the geological era of the Anthropocene. Some of these studies have the particularity of highlighting the existence of an ecological footprint anchored in factors that are more common than one would expect: the gradual extinction of animal and plant species, as a result of human practices, for example. Under the very suggestive title “Ecopoetry: Words in Space and Poets as Place-Makers”, the publishers introduce the volume with a poetic question - “Can Poetry Save the Earth? (2009) -, a question posed by John Felstiner who, in fact, quotes a poem by John Keats, written in 1816, “On the Grasshopper and Cricket”: “[t]he poetry of the earth is never dead. […] the poetry of earth has lived up to this claim.”1 This issue of changing visual landscapes and soundscapes reinforces the idea of the transformation of natural places that, in the past, inspired the arts – poetry, music, literature, painting... We are convinced that, with the disappearance of these landscapes, the arts themselves will become darker and more oppressive, without any power to celebrate the beauty of the world, or to incite hope. For the most pessimistic, the power of poetry – and of words – to save the earth is diminishing. But Serrano and Gámez-Fernández consider that

Ecopoets are […] place-makers: in writing ecopoems that direct readers’ attention to the complexities of the more-than-human world. […] Ecopoetry might ultimately help us grasp humanity’s position in the larger scheme of things” (Serrano and Gámez-Fernández 2021, 1, 4).

This warning from poetry is common to other arts, namely cinema, which, through the econarratives of films, and by showing dimensions of “deep ecology”, contributes to the dismantling of ideas of hierarchies of life on earth, and their respective supremacies.

Taking the econarrative as a starting point, this paper examines The Anthropocene Project, a multidisciplinary work by Jennifer Baichwal, Edward Burtynsky, and Nicholas de Pencier. The project “investigates human influence on the state, dynamic and future of the Earth”2 combining scientific research and print media with art, film, virtual and augmented reality, offering an immersive and multifaceted narrative that invites the audiences to reconsider their relationship with their planet. More than a collection of texts and visuals, The Anthropocene Project presents a narrative about human impact, ecology, interconnectedness, scale, and accountability.

Putting in dialogue Stibbe’s econarrative framework (Stibbe 2024) with Anna Tsing’s “arts of noticing” (Tsing 2015), this paper aims to explore how The Anthropocene Project crafts an affective, intellectual, and ethical experience that challenges viewers to see the Earth, and their role within and about it, differently. And we may observe how through its experimental form and immersive strategies, the project foregrounds the power of noticing and the necessity of connecting ecological crises to broader questions of justice, sustainability, and interspecies coexistence.

(Eco)Narratives: the power of stories

“Ce qui a créé l’humanité, c’est la narration...” (Pierre Janet 1928, 261)

Narratives are ways of ordering the world, which is, as a rule, chaotic. They are, therefore, fundamental to the understanding and survival of the Earth and all the beings that inhabit it. However, as Stibbe states, narratives are not just representations of the past, or of a pre-existing reality. Narratives are greater forces punctuated by a power of creation. It is this power to create worlds that cinema can claim, by adopting the

econarratives, which are narratives that involve not just humans, but also other species and the physical environment in interaction with each other. At this time in history, when human activity is destroying the ecosystems that life depends on, we need econarratives that can help us think about the basis of our culture, society, economic systems, and our relationships with other species and the physical environment. (Stibbe 2024, 16).

It is, therefore, within this framework of analysis that we convene our case study: The Anthopocene Project.

The arts of noticing

Anna Tsing’s concept of “arts of noticing” complements the idea of econarratives by emphasizing a practice of observation that is both radical and attentive. In The Mushroom at the End of the World (Tsing 2015), she offers a compelling mode of resistance to the extractive and instrumental worldview fostered by capitalist modernity. Noticing, for Tsing, is not a neutral act of observation but a deliberate, situated practice of attention – one that resists the erasure of complexity, interdependence, and the unruly vitality of the human and more-than- human world:

only an appreciation of current precarity as an earthwide condition allows us to notice this – the situation of our world. As long as authoritative analysis requires assumptions of growth, experts don’t see the heterogeneity of space and time, even where it is obvious to ordinary participants and observers. […] To appreciate the patchy unpredictability associated with our current condition, we need to reopen our imaginations. (Tsing 2015, 4-5).

For Tsing, the opening of our imagination, allows for new models of thinking, and practices of knowing and being. However, this firstly requires being attentive. In the realm of artistic and cinematic practices, this attentiveness may translate into a way of seeing that moves beyond surface comprehension or spectacle. It then becomes a sensory, embodied way of engaging with epistemological, material, and ecological realities that are often hidden or rendered illegible.

Looking at the interactive and immersive media, such as those employed in The Anthropocene Project, they are potentially uniquely positioned to cultivate this kind of attention, of exploring and noticing. When audiences are “placed inside” a lithium or marble mine, surrounded by the sounds and sights of an ivory burn, or follow the feet of a person rummaging through the enormous landfill, they are not just shown a landscape, they are also asked to inhabit it, to dwell in its textures, scale, and contradictions, and hence to observe the effects of environmental changes as a result of human intervention, and notice its impact. This affective intensity aligns closely with Tsing’s call to notice what is usually dismissed as peripheral: the lingering traces of industrial intervention, the slow violence of climate change, the micro-histories of land exploration and extraction. When audiovisual forms linger, when they slow down or magnify the banal and the vast, they invite a mode of attention that resists the culture of speed and simplification, inviting us to see relationally, across different geographies and species.

This shift from detached observation to embodied presence echoes theories of cinematic perception that emphasize the role of the body and the senses. Rather than treating vision and aural senses as a distant, objective faculty, such approaches understand spectatorship as almost tactile, sensible, affective, and ethical. As an audience, we feel, absorb, and respond. However, such attention is not cultivated in isolation. It is shaped and structured by media systems themselves. Contemporary communication infrastructures often reward immediacy, distraction, and scale – precisely the conditions that dull our perceptual capacities. To counter this, projects like The Anthropocene Project that have time, people and resources to span through number of years and different disciplines and media outputs, function as counter-media, reorienting attention away from the logic of the feed and toward a slower, denser kind of looking, and thus noticing. They become exercises in patience and in tuning the viewer into the frequencies of ecological entanglement that are otherwise drowned out by the noise of everyday digital life.

This kind of perceptual recalibration also speaks to anthropological understandings of movement and encounter. Rather than treating both natural and human made landscapes as static scenes, immersive and durational media forms position the audiences as wanderers – moving through them and encountering its histories in embodied ways. In doing so, they enact a different ethics of attention, one grounded in being with and among rather than above or outside. Clearly, assisting a documentary, an interactive or VR show will not replicate being there, in those landscapes, however, learning about, acknowledging, and being immersed in slow pace, leaves time and space for contemplation and reflexion about the shown realities and human impact, from micro to macroscale.

In this convergence of anthropology, philosophy, visual studies, and media theory, the act of noticing becomes something more than a tool for critique. It becomes a method of world-making – a way of relating to landscapes, images, and each other that foregrounds interdependence and responsibility. Within The Anthropocene Project, this ethic emerges not only through content, but through form, and together, these choices create the conditions for a new kind of engagement, one that draws the viewer into a state of noticing that is not passive or simply aestheticizing, but deeply implicated, embodied, and potentially transformative.

The Anthropocene Project: an overview

The Anthropocene Project is the product of a long-standing collaboration between the multiple award-winning team – filmmaker Jennifer Baichwal, photographer Edward Burtynsky, and cinematographer Nicholas de Pencier. The project spans several interlacing media platforms: a) three feature-length documentaries – Manufactured Landscapes (2006), Watermark (2013) and ANTHROPOCENE: The Human Epoch, which accompany the research of the Anthropocene Working Group in mapping large-scale human transformations of the Earth; b) a photography collection; c) a travelling interactive museum exhibition, which uses “both new and traditional lens-based art to create an innovative and dynamic expression of humanity’s incursions on the planet;” d) interactive experiences, such as 360º video, cinematic VR and interactive gigapixel essays; and e) a companion book that accompanies the film and museum shows and consists of images and essays by the three principal authors, specially commissioned poems by Margaret Atwood and reflections offered by the Anthropocene Working Group scientists.

The goal of the project, in their own words, is “to explore a critical point in Earth and human history, and expand awareness of our species’ reach and impact.”3 It was conceived inspired by the research of the Anthropocene Working Group – a group of international scientists, which includes humanists, social scientists, lawyers, geologists and stratigraphers, who advocate for declaring a new geological epoch defined by human impact and for whom, the Anthropocene already “possesses geological reality.”4 But rather than merely illustrating this research and its impact, Baichwal, Burtynsky and de Pencier set out to evoke it viscerally and emotionally. The result is a layered, multimodal work that engages us, visually, aesthetically and thoughtfully. Sprouting from research, the project offers another possibility for creators, scientists and audiences, to use the cinema itself as a process of inquiry. That is, we may look at research as

[…] a creative and transformative mode of inquiry relying on specific “materials and sources”, which become method, medium, and mediation. Cinema as inquiry is then ‘re- searching’, or searching again, which includes temporal and spatial dimensions and the possibility of generating novel forms of knowledge. (Negrón-Muntaner 2023, 79).

Econarratives – from linear to immersive – the case of Gigapixel Essays

Significant part of The Anthropocene Project’s exposure came from the Anthropocene – The Human Epoch, feature documentary as probably the most “conventional” audiovisual output. Aligning with the project’s objective, it is simultaneously a document that aims to support the proposal for the inclusion of the Anthropocene in the geological time scale.

This is a reflective film with surprising and truly impactful images, collected from various points around the globe; cities polluted by metal extraction industries in Russia; piles of ivory for illegal trade, extracted from thousands of elephants killed in African natural parks; mountains destroyed in Italy to collect Carrara marble, from which sculptures are also made; the Atacama desert contaminated by the extraction of lithium that feeds the factories that make car and cell phone batteries, etc.; coal mines in Germany, where the world’s largest excavators increasingly occupy the lands of expropriated farmers; ancient Canadian and Nigerian forests decimated to feed the timber export industry; Dantesque landscapes in Shanghai, Osaka, Houston; mountains of garbage in Nairobi, which – in due time – will settle and become part of what is already called the “technosphere”; tunnels that tear through the bowels of the earth, to make travel faster; phosphate mines in Florida, which is far from the most common tourist image; Oil refineries in Texas; Gudong Sewall in China; Venice sinks a little more with each passing year; coral reefs in Indonesia and Australia dying as waters acidify; extinct or on the verge of extinction animal species, preserved only in zoos or protected by heavily armed guards...

Although it is not a film with a single narrative, the call for the protection of ecosystems – namely animal and plant species –, in parallel with the dystopian vision of cities and natural landscapes transformed by human action, make it an econarrative, in the sense of Arran Stibbe: “individually, econarratives can serve ecological goals to greater or lesser extents, or even work against them, so are therefore open to criticism.” (Stibbe 2024, 30). In any case, econarratives are very important to “open up paths for readers to critically evaluate the dominant narratives of the unequal and unsustainable society around them and search for new narratives to live by.” (Stibbe 2024, 36).

Instead of linearly presenting the problem, detailing its causes, and then proposing solutions, The Anthropocene Project seemingly resists the narrative closure. Interestingly, although implicit, it does not offer a straightforward moral or call to action. Instead, through this multimodal work, it asks the audiences, both online and offline, to engage with discomfort and to reflect on complicity.

The use of immersive formats plays a crucial role. Immersion, as a metaphor, “derived from the physical experience of being submerged in water” and as was already suggested by Janet Murray in 1997,

We seek the same feeling from a psychologically immersive experience that we do from a plunge in the ocean or swimming pool: the sensation of being surrounded by a completely other reality, as different as water from air, that takes all our attention, our whole perceptual apparatus. (Murray 1997, 98)

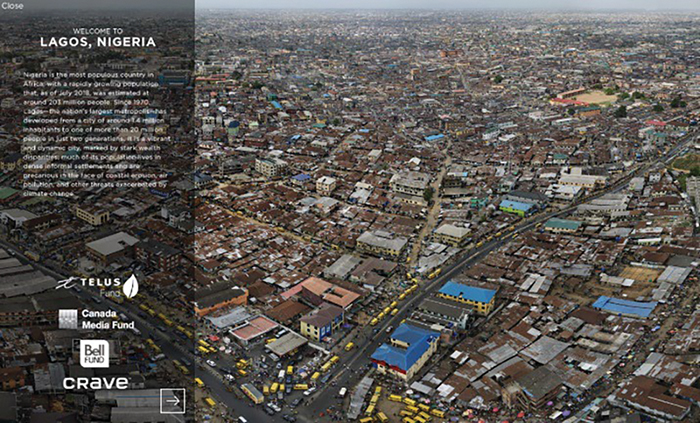

Hence, forthwith, we will be focused here particularly on what the project authors designate as (Interactive) Gigapixel Essays.5 They are easily accessible on the project’s website, and they do not depend on applications or virtual and augmented reality peripheral equipment, such as VR headsets or other special visualization gear. The Gigapixel Essays do not only decentralize narrative authority, but it is almost completely eliminated. Instead, though the three available chapters placed in Cathedral Grove in Canada, Lagos in Nigeria and Carrara in Italy, the spatial presence is emphasized, aiming at a disruption of passive consumption followed by the free roaming, zooming in and out of an image, exploring the space and place, calling to subtle noticing. The effect it produces goes beyond mere observation and beyond admiration for rather stunning visuals, inviting us to empathetically witness the beauty and the decay. It asks for noticing the details in order to fully explore the narrative.

Upon starting one of the chapters, we are introduced to the context of our immersion. For instance, in the case of Lagos we learn that Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa, with rapidly growing population that was estimated at around 203 million people at the time of the production, while the Lagos itself has more than 20 million. Simultaneously vibrant and dynamic, it is also precarious, with stark inequalities.

Starting form the macro perspective, we are subsequently invited to zoom in and out, explore, navigate around the image, and locate several “visual triggers.” It is only by noticing them, that it is possible to dig deeper into the stories of the city – be it an audio immersion, or video depicting different parts of the megalopolis, the people and their stories.

These visual triggers function as narrative anchors, they operate as points of entry, as moments of heightened attention that invite associative, and affective engagement, asking for active participation in the meaning-making process. In this sense, the Gigapixel Essays exemplify a post-narrative form of spatial and non-linear engagement, in which we should

distinguish a minimal form of transportation – thinking of a concrete object located in a time and place other than our present spatio-temporal coordinates – from a strong form of the experience, by which “thinking of” means imagining not only an object but the world that surrounds it, and imagining ourselves contained in this world […]. The minimal form of transportation is built into language and the cognitive mechanisms of the mind; we cannot avoid it. But the richer forms depend on the resonance in the reader’s mind of the aesthetic features of the text: plot, narrative presentation, images, and style. (Ryan 2001, 96)

The interactivity is not goal-oriented in a gamified sense, but instead invites exploratory wandering, evoking what Michel de Certeau termed the “tactics” of everyday life, microscopic movements through a space that imbue it with personal meaning (de Certeau 1984).

This spatial mode of engagement echoes a broader shift in digital humanities and media studies toward what Johanna Drucker describes as “performative materiality” – an understanding of digital interfaces as spaces where knowledge is not just displayed but enacted (Drucker 2016). As users navigate the high- resolution image space, each gesture becomes a performative act of attention.

Furthermore, by staging its narratives through high-definition, zoomable images, each chapter of the Gigapixel Essays underscores the politics of visibility. What is made visible, and at what resolution, matters. And this is particularly heightened when we are engaging with themes of ecological preoccupation, environmental degradation, and inherent global inequalities. In the Gigapixel Essays, these issues become slowly legible not through expository narration, but through an audience-driven exploration of the visual field. This creates an ethical imperative to look more closely, to slow down, and to attend to the often-overlooked textures of our environment. By foregrounding the act of looking, and noticing, as both a privilege and a responsibility, the immersive techniques of the Gigapixel Essays, and The Anthropocene Project in general, they gesture towards a more situated and participatory form of knowledge production, one that aligns with environmental, as well as decolonial and feminist media critiques, that call for plural, embodied ways of knowing and seeing.

Ultimately, the immersive format of the (Interactive) Gigapixel Essays redefines what it means to explore and “experience” a narrative. It is not about moving from a beginning to an end, nor about consuming information in a passive or linear manner. Rather, it is about becoming attuned to the multiplicity of stories embedded in place, and about cultivating the capacity to see complexity in stillness.

Conclusion: The Challenge of Ecological Imagination

In 2013, the book Transnational Ecocinema. Film Culture in an Era of Ecological Transformation brought together some profound reflections on the political power of documentary in relation to the “ecological imagination”, as described by Roberto Forns-Broggi, in the chapter “Ecological Imagination and Ecocinema”. According to Forns-Broggi:

ecological imagination is a key concept for understanding the connections and systems of the natural world. […] an ecological imagination depends on both conscious and unconscious mechanisms of control in our dominant rationality. [And] Ecocritical cinema has enormous potential for the investigation of the ecological imagination.” (Forns-Broggi 2013, 85)

The author would return to this issue, in greater depth, in 2016, with his book Knots like Stars: The ABC of Ecological Imagination in our Americas, where he expresses his intention to reflect “honestly” (the term is its own)

on the ecological imagination not only through the word, but also through the visual image, given my [his] creative interest in crossing and mixing creative genres such as poetry and film. (Forns-Broggi 2016, 5)

For the author, the necessary condition for the exercise of ecological imagination is the construction of a field of reflection of the common, with regard to ecology. But he adds that the interception and juxtaposition of projects is important, as is the existence of an assembly of participant-creators, in a process that he calls the “promiscuity of collaborations” (Forns-Broggi 2016, 5) in “sites of construction that have no end.” (Forns-Broggi 2016, 5), referring, in this case, explicitly to eco-art. Despite the context expressed, these reflections also seem to frame, very clearly, the practice of contemporary interactive documentary and, in particular, the Project we analyzed.

[…] one after the other—

titles, news, articles

books, shows, conferences.

this debate is older than me [us]

but it’s up to me [us] to solve it.

(Pärtna 2024, 173)

Final Notes

1The complete poem by John Keats goes as follows: “The poetry of earth is never dead: / When all the birds are faint with the hot sun, / And hide in cooling trees, a voice will run / From hedge to hedge about the new-mown mead; / That is the Grasshopper’s— he takes the lead / In summer luxury,—he has never done / With his delights; for when tired out with fun / He rests at ease beneath some pleasant weed. / The poetry of earth is ceasing never: / On a lone winter evening, when the frost / Has wrought a silence, from the stove there shrills / The Cricket’s song, in warmth increasing ever, / And seems to one in drowsiness half lost, / The Grasshopper’s among some grassy hills.” In A Greeting of the Spirit: Selected Poetry of John Keats with Commentaries (2022). Susan J. Wolfson (Ed.). Harvard University Press, 67.

2See: https://theanthropocene.org/

3See: https://theanthropocene.org/

4https://www.anthropocene-curriculum.org/contributors/anthropocene- working-group

5https://theanthropocene.org/interactive/gigapixel-essays/

Bibliography

Aparício, Maria Irene. 2024. “Cinema of/for the Anthropocene: Affect, Ecology, and More-Than-Human Kinship.” In Cinema: Journal of Philosophy and the Moving Image, 16(1), 211–219.

De Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley – Los Angeles – London, University of California Press.

Drucker, Johanna. 2016. “Diagrammatic Form and Performative Materiality.” Disrupting the Humanities: Towards Posthumanities 19 (2).

Forns-Broggi, Roberto. 2013. “Ecological Imagination and Ecocinema.” In Kääpä, Pietari and Tommy Gustafsson, eds. Transnational Ecocinema. Film Culture in an Era of Ecological Transformation. Bristol: Intellect Books.

Forns-Broggi, Roberto. 2016. Knots like Stars. The ABC of Ecological Imagination in our Americas. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Janet, Pierre. 1928. L`Évolution de la Mémoire et de la Notion du Temps, Paris, A. Chahine.

Martínez Serrano, Leonor María and Cristina M. Gámez- Fernández. 2021. Modern Ecopoetry. Reading the Palimpsest of the More-Than-Human World. Leiden - Boston: Brill.

Murray, Janet H. 1997. Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. New York: The Free Press.

Negrón-Muntaner, Frances. 2023. “Cinema as Inquiry: On Arts, Knowledge and Justice.” In Blaagaard, Bolette B., Sabrina Marchetti, Sandra Ponzanesi and Shaul Bassi, eds. Postcolonial Publics: Art and Citizen Media in Europe. Venice: Edizioni Ca’Foscari – Venice University Press.

Pärtna, Maarja. 2024. “Four Poems.” In Irr, Caren et al., eds. Environmental Futures: An International Literary Anthology. Waltham: Brandeis University Press.

Paszkiewicz, Katarzyna and Andrea Ruthven, eds. 2025. Cinema of/for the Anthropocene:Affect: Ecology, and More- than-Human Kinship. New York: Routledge.

Rust, Stephen Salma Monani and Sean Cubitt. 2015. Ecomedia. Key Issues. New York: Routledge.

Ryan, Marie-Laure. 2001. Narrative as Virtual Reality: Immersion and Interactivity in Literature and Electronic Media. Baltimore - London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Stibbe, Arran. 2024. Econarrative: Ethics, Ecology, and the Search for New Narratives to Live By. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Wolfson, Susan J., ed. 2022. A Greeting of the Spirit: Selected Poetry of John Keats with Commentaries. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Filmography

Anthropocene: The Human Epoch. 2018.

Websites

The Antropocene Project. https://theanthropocene.org/