Abstract

The impact of the internet on education has been substantial and has even been posited as imposing an educational paradigm shift. While online learning provides benefits such as flexible session times and self-paced learning, internet-based learning has been criticized as invoking less engagement than other platforms. Indeed, taped lectures, instructional videos and even documentaries have all received significant criticism as not sustaining attention in an adequate manner. Accordingly, the hybrid domain of “edutainment” (didactics frequently presented by means of videos or short films, but with a notably entertaining context meant to enhance interest in the relevant didactics) has begun to receive greater attention, even at prestigious academic centers. The ideal format for edutainment-based presentations is however, unknown. In this regard, edutainment stories presented within an overly immersive dramatic narrative can notably distract the student from the didactics, thus the basic structure of formats which genuinely enhance the didactic impact of edutainment presentations require investigation. The current study presents a two-tiered narrative structure loosely embedded within a music-video-like collage employing variable degrees of divergent exposition and narrative in a manner that allows the student to more effectively process or acknowledge the didactics. This theoretical framework is proposed to constitute a moderately novel hybrid film genre (hybrid experimental, music video formatted, educational docufiction, or HEMVFED), and initial investigation suggests that it is an effective edutainment format. Moreover, integration of HEMVFED edutainment videos with educational technology can refine and detail video content, thus imparting even greater didactic utility.

Keywords: Unconventional Documentary, Brain Circuitry, Edutainment, Music Video, Neuropsychology.

Introduction: Impact of the Internet on Education, A Portal for Edutainment

The last few decades have been characterized by a pervasive impact of the internet across myriad dimensions of daily life, including healthcare, several municipal functions, and various aspects of the business world (Romaniello and Chircu 2018). Development of the internet has also had a substantial effect on education and has even been posited as prompting an educational paradigm shift (Harasim 2000; Gilardi and Reid 2014). As further catalyzed by the covid pandemic, education has perhaps transitioned from primarily being a teacher driven process to one where the student is expected to take greater initiative and assume more responsibility for several aspects of their learning experience (Dacre and Fox 2000). This transition has involved both positive and negative sequalae. For example, even though online education provides benefits such as flexible session times, self-paced learning, and greater capacity for customizing various features of the didactic process (Rueda et al. 2024), internet-based learning has also been criticized as invoking less motivation and engagement (Basar et al. 2021; Akpen et al. 2024; Zeng et al. 2024; Schindler et al., 2017). Moreover, online presentation of taped lectures, instructional videos, and even documentaries have all received criticism as not sustaining attention in an adequate manner (Hwu 2023; Nitkin 2018; Godmilow 2002; Schwarz 1976).

Edutainment: What is the Best Format?

From the ancient Greek era (Trapp 1996), through European medieval (Loucky 2008) and American colonial times (Vinovskis 1987), edutainment, i.e. presentation of didactics within an entertaining context designed to enhance engagement, has enjoyed an extensive history. More recently, as greatly sculpted by technological developments, the modern era has witnessed a transformative and expansive trajectory wherein the scope of edutainment has extended beyond its more traditional purview of theatrical oratory and educational videos to permeate gaming, augmented and virtual reality, social media, and even mobile phone apps (Nunez 2020; Ottowitz 2024). Thus, while the conceptual framework of edutainment persists with an agenda to simply advance learning within a more enjoyable and engaging context (Ackerman and Murphy-Browne 2022; Tze et al. 2016), the diverse array of possible edutainment formats continue to evolve. Although this evolution holds potential for a range of experimental and creative formulations, such a trajectory can certainly benefit from research which evaluates the capacity of any particular edutainment format to advance the didactic agenda in an effective manner. Indeed, some edutainment formats may actually interfere with effective cognitive processing of the relevant didactics and moreover, excessive use of technology may at times become counterproductive (Sharif et al. 2010; Schindler et al. 2017; Okan 2003).

In particular regard to short film or video edutainment, while the general structure of instructional videos has received rudimentary investigation (Niekrenz 2024; Buchner 2018; Brame 2016), the ideal structure or specific format in which to present entertaining educational video short films is largely unknown (Applequist 2025; Pasawano 2015). For example, although the documentary may perhaps be the most intuitively obvious edutainment format, research has shown that viewers frequently find documentaries to be incomplete and artifical. Indeed, documentaries have even been judged as inferior to soap operas in the communication of educational material (Davin 2003). Alternatively, edutainment content presented within an overly immersive dramatic narrative can distract the student from the relevant didactics (Bekalu et al. 2007; Cohen, Shavalian, and Rube 2015). Thus, in summary, although edutainment narratives have generally been well received as holding great potential to benefit the educational process (Landrum, Brakke, and McCarthy 2019; Pasawano 2015), formatting and genre issues of basic relevance to the challenge of enhancing audience appeal and optimizing a didactic agenda still require substantial investigation (Turner, Lee, and LeDoux 2023).

A Candidate Edutainment Formula for Education: The Primacy of Music and an Unconventional Use of Narrative and Exposition

Narratology has been defined as the formal study of how perception, cognition, and emotion are affected by stories and story structure (Cutting 2016). As perhaps first proposed by Aristotle, a story can be divided into three parts, a beginning, middle, and end (Dung 2016). While this general sentiment has been further advanced by Syd Field in his well received, highly popular textbook, Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting; A step-by-step guide from concept to finished script (1979), such a formulation has been the target of repeated criticism (Tobin 2016; Brutsch 2015; Horton 2015). Indeed, perhaps the most classic act structure conception, that of Gustav Freytag, as introduced in 1863 in the classic text Technique of the Drama, An Exposition of Dramatic Composition and Art, proposes that the structure of stories is best approached as a five-act construct - introduction, rise, climax, return, and catastrophe (Freytag 1900, 114-140). In addition, despite the traditional formatting of three, four, or five act stories, a myriad of alternate constructs have been devised in a manner which deprioritize the significance of conforming to traditional act formats and more flexibly focus on developing the artistry of the story (Yoonmi 2021).

Extending beyond simple appreciation for the relevance of act structure to an edutainment production, the specific manner by which the didactic content is packaged, i.e. use of a narrative vs expository presentation style for the relevant factual content, frequently embodies greater salience in realizing an effective educational agenda. Substantial theorizing and empirical research have been directed toward what formally constitutes a narrative (Boyd et al 2020; Velleman 2003) and the effort of Shaffer and colleagues (2018) has generated a cohesive and laudable definition for narrative as - a story characterized by a description of a series of events about a unified subject involving causal relationships between actors and events with an accompanying sensible emotional cadence. The basic structure of the narrative is further characterized by a chronological or temporal ordering of events and some form of demarcation embodying a beginning, middle, and end. While such a definition is practically compelling, any definition will have its shortcomings. For example, a traditional chronological temporal structure for narratives has repeatedly prompted criticism (Kumar and Bachchan 2023; Seeman 2017).

In contrast to the manner in which narrative develops a story based on interaction between characters (most typically) and further develops the corresponding sequence of events in an explicitly visual manner (Nikulina et al., 2024), exposition provides more detailed secondary information, background and supporting facts, and frequently does so by means of voiceover or even text (Crittenden 2023; Decker 1974). Moreover, depending on the details of the presentation (Wolfe 2005), expository texts can be more readily comprehended and better recalled than narratives (Watts et al., 2015; Wolfe and Mienko 2007). Thus, in terms of edutainment, which is frequently ultimately oriented toward communication of facts, exposition can actually hold greater weight for the ultimate production endpoint than the dramatic narrative.

As much as a storyline with a captivating narrative and minimal use of exposition is typically embraced as the undisputed backbone of a production (Mou, Jeng, and Chen 2013), in particular regard to edutainment, development of a fully immersive, captivating story is not the primary agenda (Ottowitz 2021; Ottowitz 2024). For an edutainment production, the didactic content is intended to capture the spotlight - and perhaps even do so at the expense of a well-developed (and more conventional) storyline. While this subversive, alternate agenda may require the audience to adopt a more flexible mindset upon engaging a filmic production, more generally, the artistic grounding for film frequently involves challenging the audience to not be constrained by prior experiences and corresponding expectations. Such a perspective is readily apparent upon reconsideration of the act structure format for a story. For example, as summarized previously, while an Aristotelian 3 act vs Freytag 5 act structure may possibly apply to the majority of stories which have been produced across centuries, in reality there is very probably an extensive array of act structure formulations which may prove effective. Indeed, as summarized by the film scholar Kim Yoonmi (2021), there may be 30 or more filmic act structures, where ultimately, act structure is primarily driven and sculpted by the unique demands of the particular artistic film production being developed.

In edutainment, the goal is to use entertainment as a vehicle to transport the audience into the didactics (Ottowitz 2024; Ackerman and Murphy-Bowne 2022). Thus, what might typically be perceived as the narrative of a conventional film can quite potentially be just a gimmick facade for an edutainment production. Such a shocking realization liberates the storyline to emerge from the ashes of deconstruction in an unconventional form, i.e. narrative and exposition may now enjoy an unusual dialogue uniquely customized to enhance recall (Dasovich-Wilson, Thompson, and Saarikallio 2025; De Graaf, Sanders, and Hoeken 2016). Moreover, it is perhaps immediately apparent that effective orchestration of such a unique dialogue requires the skill of a master composer. In this regard, the capacity for music to communicate a story, generate emotion, and enhance learning and recall has been demonstrated repeatedly across many studies (Alberhasky and Durkee 2024; Ma 2022; Zaini and Yusoff 2024; Rauscher et al., 1993; Ferreri et al., 2013; Bokiev et al., 2018; Ngong 2020).

Brain Film Music Videos: HEMVFED and the Double Narrative

The artistic orientation, style and structure of music videos vary dramatically. For example, a music video can primarily involve presentation of a band performing on stage, or at the other extreme of the spectrum, it can almost constitute a short film with a relatively obvious storyline and narrative (Albernasky and Durkee 2024; Zaini, Nur, and Yusoff 2024). Indeed, the first music video to be aired on MTV in August of 1981, Video Killed the Radio Star, by The Buggles (directed by Russel Mulcahy, 1979), anticipates the ensuing commercial transition of radio based presentations of music to video based presentation of music by portraying the trajectory of a girl’s life from childhood to adulthood in conjunction with a visual narrative which show old fashioned radios being replaced by VCR televisions erupting from the ground (to replace the radios). Even though much of the video also presented clips of the band performing, the narrative agenda of the video to highlight the advent of visual media technology as replacing the primacy of audio technology is obvious and clearly resonates with the content of the lyrics (presented below in truncated form):

..They took the credit for your second symphony Rewritten by machine on new technology…

…You were the first one

You were the last one

In my mind and in my car

We can’t rewind we’ve gone too far…

Pictures came and broke your heart

Put the blame on VCR

You are a radio star

Video killed the radio star

Video killed the radio star…

While this iconic music video is artistically engaging, it eventually also proved to serve as an effective history lesson, i.e. it accurately predicted the substantial replacement of audio by video as the prevailing means of media communication (Kniaz-Hunek 2023). Thus, although not typically conceptualized as such, and even though it is clearly oriented more towards entertainment over education, it can be considered to lie within the spectrum of what constitutes an edutainment video.

More generally, the capacity for music videos to provide some version of an educational function has a long history (Kniaz-Hunek 2023). Over the last couple decades, the capacity for music videos to target specific educational domains is acquiring greater momentum [Zaini and Yusoff 2024; Hadi 2019; NPR’s Skunk Bear 2015; Ottowitz 2021]. As this unintended emerging application (use of music videos for education) seeks further acceptance as a bonified endeavor, the psychological casualties related to the burden of this potential identity crisis are noteworthy. Specifically, one’s capacity to comprehend a video or film benefits from a pre-existing awareness or familiarity with its genre. That is, expectations for events in a film or video are frequently implicitly preformatted by the type of film the audience believes they are watching (MacWhinney 2015; Nalabandian and Ireland 2019). If the viewer is uncertain as to which genre holds primary relevance, there is greater propensity to become confused by events in the clip which are vague or arbitrary and more generally, a prolonged state of ‘genre confusion’ can exist as its own distinct issue that distracts from the primary agenda of watching and enjoying the film or video clip (Leavitt and Christenfeld 2011; Elrod 2019; Ottowitz 2021).

From my personal experience with efforts to acquire an audience’s formal response to video clips, this potential dilemma, i.e. the potential confusion associated with genre ambiguity, is such an issue that it became the theme of my visual effects (VFX) master’s thesis at University of the Arts, London (UAL). The thesis research effort, entitled “Components, Formative Development, and External Critique of a Music Video Formatted Framework for Brain Science Education: the Didactic Relevance of a VFX Driven Narrative” involved a survey based evaluation of two versions of an edutainment brain science music video, one which embodied notable genre ambiguity (Emotion’s Brain SECTIONS) and a second version of the same video reformatted with a few clips which imparted a modest degree of documentary structure (Brain Waves from Outer Space). The latter video was devised in a manner such that it embodied hybrid elements of an experimental, educational docufiction video formatted in a deconstructed, nonlinear collage manner loosely resembling a music video (Hybrid, Experimental, Music Video Formatted, Educational Docufiction or HEMVFED video). In brief, subjects approved of the greater documentary structure imparted by the HEMVFED formatting (Ottowitz 2021). Subsequent research revealed that advance explicit orienting of viewers to the agenda of the HEMVFED genre as a novel edutainment entity intended to exist merely as one part of a greater topic based didactic package prompted even greater approval for the video (Ottowitz et al., 2023).

In conjunction with development of a moderately novel video genre, perhaps the most significant aspect of the HEMVFED construct is the double narrative. The ‘double narrative’ construct can be more precisely described as ‘didactic exposition embedded within a partially divergent gimmick narrative’. The gimmick narrative is the immediately apparent surface story which serves to recruit and sustain the viewer’s attention. It exists to present the particular didactics of relevance in an engaging manner. However, because the didactic exposition is loosely organized and presented as its own narrative review (Sukhera 2022), the phrase ‘double narrative’ is a sensible alternative to a very cumbersome, albeit more accurate alternative phrase “didactic exposition weighted narrative embedded within a partially divergent gimmick or surface narrative which includes very little exposition”.

The capacity for an edutainment production to potentially benefit from a double narrative structure became apparent after years of studying and devising stories and short films and informally evaluating the cognitive processing of viewer’s responses. From this effort, a notably problematic and limiting aspect of integrating a didactic backbone into an entertaining narrative was that the viewer would (most typically) become primarily immersed in the entertaining narrative and frequently ignore the didactic content. In other words, the more entertaining and engaging dimension of an edutainment video was observed to effectively hijack the viewer’s attention and inadvertently derail the viewer from the video’s educational agenda. My personal observation of this neuropsychological phenomenon is supported by studies of video immersion which have highlighted the substantial transportive power which film can impart (Hinde, Smith, and Gilchrist 2018; Wang and Tang 2021). Specifically, the transportive power associated with film immersion has been shown to derail the viewer’s capacity to sustain attention to a secondary target task (Cohen, Shavalian, Rube 2015), and thus, it is not surprising that a highly engaging dramatic narrative might inadvertently redirect the viewer away from golden nuggets of factual references scattered throughout such a narrative.

As developed during graduate studies at the University of the Arts, London, my music-video-like unconventional documentary entitled Brain Waves from Outer Space [(BwfOS) Ottowitz 2020] embodies an unconventional dialogue between dramatic narrative and didactic exposition. The music-video-like short film is 8:40 in length and includes a dramatic narrative sci-fi plot presenting cryogenically frozen humans in each of the 6-7 basic emotional states which are transferred to an alien biomass which becomes encased in artificial human shells sculpted to portray the emotional states. The neural circuitry brain network state corresponding to the each of the basic emotions is presented as part of an elaborate visual effects schema which serves to bridge the sci-fi narrative with the didactic ‘narrative review’ (Sukhera 2022) of four researchers who have made primary contributions to the psychology of human emotion [Paul Ekman and Wallace Friesen] and to the neuroanatomy of human emotion [James Papez and Paul MacLean].

In regard to the double narrative structure of BWfOS, the dramatic sci-fi gimmick narrative is presented in a deconstructed, nonlinear manner which is actively designed to interfere with a full processing and understanding of the sci-fi content which exists primarily to entertain the viewer and partly sustain their attention. The intent of this deconstructed design strategy is to actively hinder a full immersion in the dramatic storyline. In an almost subversive manner, intertwined with this gimmick dramatic narrative is the didactic exposition reviewing (presenting the research history underlying, Sukhera 2022) human facial expressions and the corresponding mediating neural circuitry. This “secondary” content is actually the target didactic for the video. Ultimately, it is moderately obvious that this didactic content, which is presented in a factually accurate manner, can be appreciated as its own separate narrative. Hence, a ‘double narrative’ is employed to more effectively sustain attention and simultaneously afford the viewer exposure to a neuropsychology research history lesson that they may not have otherwise found innately stimulating.

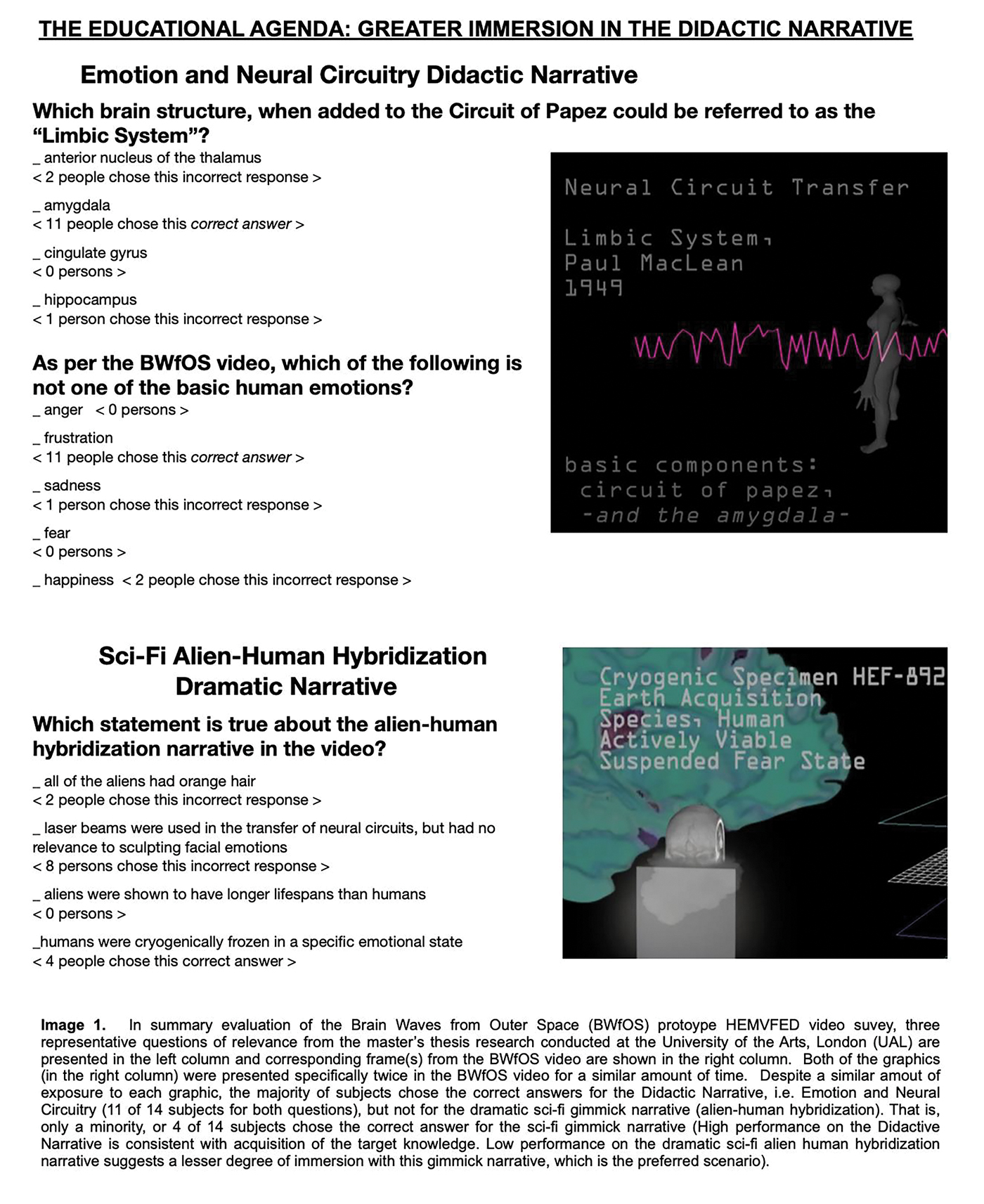

The educational effectiveness of this approach is supported by the findings of the research survey conducted as part of my master’s thesis at University of the Arts, London (Ottowitz 2021). For example, the two questions evaluating knowledge acquisition relevant to the neural circuitry of emotion were answered correctly by a clear majority of participants (12 of 14 answered question 1.5 correctly and 11 of 14 participants answered question 2.2 correctly). In addition, the question evaluating knowledge acquisition for the psychology of emotion (question 1.4) was answered correctly by 11 of 14 participants.

Conversely, as suggestive evidence that the dramatic narrative was not fully immersive, the question evaluating comprehension of the dramatic narrative (question 1.3) was answered correctly by only 4 of 14 participants. And, in terms of a rudimentary control of the relevant temporal exposure variables, the visual effects and exposition from both the dramatic sci-fi narrative and didactic narratives were presented for a similar amount of time within the full BWfOS video [two clips for test question relevant didactics, 1:51-1:59 and 7:31-7:33, and two clips for the test question relevant sci-fi drama, 2:38-2:42 and 5:44-5:50 (Ottowitz 2021, 2020)]. Thus, the learning outcome wasn’t simply a reflection of the number of clip exposures or total time of exposure (i.e. in regard to these specific test questions, both the dramatic narrative and didactic narrative involve 2 clips and both are presented for a total of 10 seconds). As detailed previously, the dramatic sci-fi narrative (alien-human hybridization) was merely a surface ‘gimmick narrative’ presented in an intentionally deconstructed and nonlinear form aiming to merely engage subjects in a passive secondary manner, i.e. in an incomplete or superficial manner relative to the didactic narrative (emotion and neural circuitry), which was intentionally presented in a more intelligible manner. An excerpt of this survey, with explicit presentation of three relevant questions (1.3, 1.4, 2.2) is presented in Image 1, and the full survey is available in the appendix of my UAL master’s thesis (Ottowitz 2021).

Merely One Part of the Picture: Relevance of Spiral Curriculum, Interactivity and Technological Innovation

Despite the participant’s positive performance on the relevant knowledge-based questions from the UAL survey, it could certainly be argued that as an isolated learning experience, a simple viewing of the Brain Waves from Outer Space (BWfOS) video has perhaps rather limited didactic utility. While the video does include several teaching points, in contrast to a conventional documentary, these points were presented with only a modest amount of detail and limited context. This approach however, was intentional and is aimed at reducing the cognitive load that can be problematic with instructional videos embodying substantial information density (Brame 2016). Thus, BWfOS, as an exemplary HEMVEFD edutainment video, is primarily meant to serve as a complementary excursion from the potential tedium associated with prolonged initial obligatory study of a subject with which a student may have limited familiarity (in this case, emotion and neural circuitry). More generally, initial contact with any new subject matter can (potentially) find the student quickly pummeled by an avalanche of manuscripts, textbook chapters, and lectures that may, in reality, be relatively uninspired and are simply aimed at conveying as much information as possible. Such a process can be criticized as an overwhelming and perhaps unconstructive ordeal (Klerings et al., 2015). Such a study effort is probably familiar to most students, but especially students at competitive colleges and certainly in graduate settings such as medical school. For students who become bored with and perhaps even annoyed by such a routine, edutainment videos provide an effective escape which allows the student to take a break from intensive studies, yet still learn (Kuzmicz 2008).

An edutainment video however, can certainly serve as more than merely a pleasurable, complementary, constructive distraction. For example, the original selection of didactic content for BWfOS was approached through the organizational lens of a ‘narrative review’ (Sukhera 2022) of the history of the psychology and neuroanatomy research underlying human emotion. Thus, as an educational tool, it does provide an effective, concise introduction to a potentially overwhelming topic. The obvious limitation of any concise introduction however, is the necessary reduction of scope and exclusion of content which possibly should have been included.

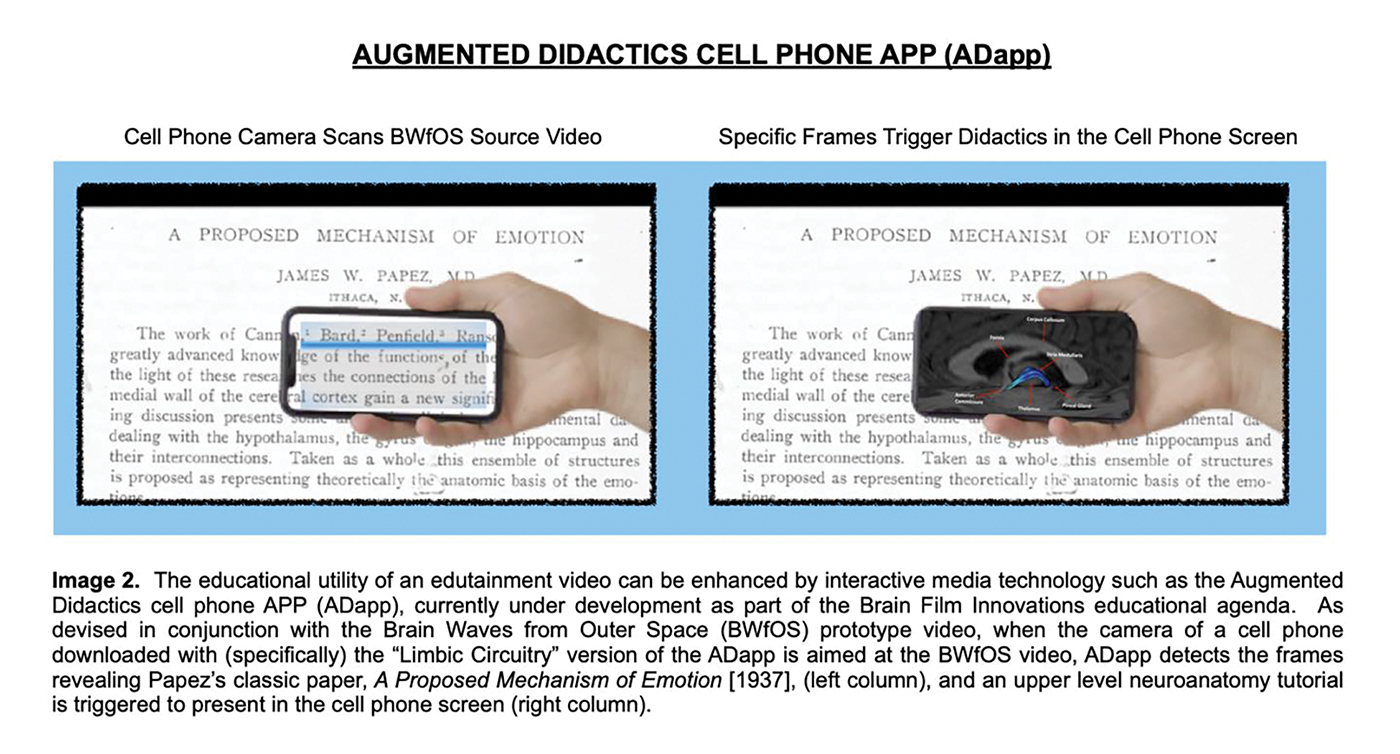

In order to address this issue, in 2023 the HEMVFED project (Ottowitz 2021) was revisited through the portal of interactive educational technology, which resulted in development of the Augmented Didactics cell phone APP (ADapp, Ottowitz et al., 2023; Ottowitz 2024). The ADapp is designed to place an introductory edutainment video more at the center of a learning effort. That is, upon viewing an edutainment video combined with use of the ADapp, the introductory didactic content of the edutainment video can acquire greater context, explanation, and additional factual details and thus resonates with the spiral curriculum framework advanced by Jerome Bruner (Masters and Gibbs 2007). The ADapp intends to harness the engagement inspired by the edutainment video and carry that momentum through to more fully motivated learning sessions where the learning is further augmented by supplemental tutorials, i.e. the learning process has generally been shown to benefit from technology based interactivity (Alam and Mohanty 2023; Aulia et al., 2024).

Image 2 presents an example of implementing the ADapp. In brief, the viewer aims their cell phone camera at the edutainment video (EV) and specific frames from the EV trigger the ADapp to play tutorials in the screen of the cell phone (ADapp is under commerical development, but not currently available).

Conclusion

In concert with the profound impact that the internet and advances in technology have had on the manner in which the current (and upcoming) generation(s) are exposed to and process information, the educational landscape has also morphed and novel, unconventional didactic strategies have infiltrated video and various supplemental, technologically grounded educational tools. Accordingly, traditional lecture presentations and video documentaries may benefit from a reformatting of their respective strategies. In particular regard to short instructional and documentary films, edutainment strategies are emerging with greater momentum and also acquiring greater acceptance. This manuscript has summarized research investigating one edutainment formatting strategy, HEMVFED (the Hybrid, Experimental, Music Video Formatted, Educational Docufiction genre), which harnesses the cognitive and emotional impact of music and an atypical, yet calculated implementation of expository narrative intertwined with a divergent dramatic narrative can have on the learning process. Small sample size (n=14) survey results have shown initial promise for this strategy, which requires more intensive investigation and further development within the context of interactive educational technology.

In conclusion, while coupling an edutainment video with interactive technology holds the potential to make an important contribution to the ever-changing landscape of modern education, hopefully the emerging momentum of edutainment may further blossom to find the spirit of the HEMVFED genre reincarnated across myriad formulations. For example, in contrast to the conventional neuroanatomy lecture experience, consider the prospect of an XR professorial avatar (Yip 2023) guiding students through an interactive model of the brain occurring in the broader edutainment context of an experimental, musically grounded, deconstructed, unconventional narrative exposition!

Bibliography

Ackerman, Amy S, Murphy-Bowne, Mary J. 2022. “Visual Edutainment to Engage Online Learners.” in Seeing across Disciplines: The Book of Selected Readings 2022, 44-53. International Visual Literacy Association.

Alam, Ashraf., Mohanty, Atasi. 2023. “Educational technology: Exploring the convergence of technology and pedagogy through mobility, interactivity, AI, and learning tools.” In Cogent Engineering 10:2, 2283282.

Alberhasky, Max., Durkee, Patrick K. 2024. “Songs tell a story: The arc of narrative for music.” in PLoS ONE 19(5):1-13.

Akpen, Catherine N., Asaolu S, Atobatele S, Okagbue, Hilary, Sampson, Sidney 2024. “Impact of online learning on student’s performance and engagement: a systematic review.” in Discover Education 3:205.

Applequist, Janelle. 2025. “Using Narratives to Promote Risks and Risky Products: Cautions and Considerations.” in Frontiers, available at https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/60444/using-narratives-to-promote-risks-and-risky-products-cautions-and-considerations

Aulia, Hartika., Hafeez, Muhammad., Mashwani, Hazrat U., Careemdeen, Jalal D., Syaharuddin, Maryam M. 2024. “The Role of Interactive Learning Media in Enhancing Student Engagement and Academic Achievement.” in International Seminar on Student Research in Education, Science, and Technology 1:57-67.

Basar, Zulaikha M., Mansor, Azlin N., Jamaludin, Khairul A., Alias, Bity S. 2021. “The Effectiveness and Challenges of Online Learning for Secondary School Students – A Case Study.” in Asian Journal of University Education 17(3):119-129.

Bekalu, Mesfin A., Bigman, Cabral A., McCloud, Rachel F., Lin, Leesa K., Viswanath, Vish K. 2007. “The relative persuasiveness of narrative versus non-narrative health messages in public health emergency communication: Evidence from a field experiment.” in Preventive Medicine 111:284-290.

Bokiev, Daler., Bokiev, Umed., Aralas, Dalia., Ismail, Liliati., Othman, Moomala. 2018. “Utilizing Music and Songs to Promote Student Engagement in ESL Classrooms.” In International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 8(12):315-332.

Boyd, Ryan L., Blackburn, Kate G., Pennebaker, James W. 2020. “The narrative arc: Revealing core narrative structures through text analysis.” in Science Advances 6:1-9.

Brame, Cynthia J. 2016. “Effective Educational Videos: Principles and Guidelines for Maximizing Student Learning from Video Content,” in CBE - Life Sciences Education 15(4):es6.

Brutsch, Matthias. 2015. “The Three-Act Structure: Myth or Magical Formula?” in Journal of Screenwriting 6(3):57-79.

Buchner, Josef. 2018. “How to create Educational Videos: From watching passively to learning actively.” in R&E-SOURCE 12:1–10.

Cohen, Anna-Lisa., Shavalian, Elliot., Rube, Moshe. 2015. “The Power of the Picture: How Narrative Film Captures Attention and Disrupts Goal Pursuit.” in PLoS ONE 10(12): e0144493.

Crittenden, Roger. 2023. “Film and the Disembodied Voice” in International Journal of Film and Media Arts 8(3):24-37.

Cutting, James E. 2016. “Narrative theory and the dynamics of popular movies.” in Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 23(6):1713–1743.

Dacre, Jane E., Fox, Robin A. (2000). “How should we be teaching our undergraduates?” in Annals of Rheumatic Disease 59(9):662-7.

Dasovich-Wilson, Johanna N., Thompson, Marc., Saarikallio, Suvi. 2025. “The characteristics of music video experiences and their relationship to future listening outcomes.” in Psychology of Music 53(1):36–54.

Davin, Solange. 2003. “Healthy viewing: the reception of medical narratives.” in Sociology of Health & Illness 25(6):662–679.

Decker, Randall E. 1974. Patterns of Exposition 4. Boston: Little, Brown & Company.

De Graaf, Anneke., Sanders, Jose M., Hoeken, Hans. 2016. “Characteristics of narrative interventions and health effects: A review of the content, form, and context of narratives in health-related narrative persuasion research.” in Review of Communication Research 4:88-131.

Dung, Vo V., Drang, Do TT., Vy, Bui TK. 2016. “Aristotle’s Educational Ideas” in European Journal of Education Studies 2(9):115-126.

Elrod, James M. 2019. “Navigating the Nebula: Audience affect, interactivity, and genre in the age of streaming TV.” Participations - Journal of Audience and Reception Studies 16(2):167-195.

Ferreri, Laura., Aucouturier, Jean-Julien., Muthalib, Makii., Bigand, Emmanuel., Bugaiska, Aurelia. 2013. “Music improves verbal memory encoding while decreasing prefrontal cortex activity: an fNIRS study.” in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7:1-9.

Freytag, Gustav. 1900. Technique of the Drama, An Exposition of Dramatic Composition and Art. translated by Elias MacEwan, Chicago: Scott, Foresman and Company. 114-140.

Gilardi, Fillipo., Reid, James. 2014. “Transmedia storytelling: paradigm shift in literary studies. Narrative, adaptation, teaching and learning.” in Deterritorializing Practices in Literary Studies: Contours of Transdisciplinarity, edited by Maria C. Guzmán, and Alejandro Zamora, 103-121. York University.

Godmilow, Jill. 2002. “Kill the Documentary as We Know It.” in Journal of Film and Video 54(2/3):3-10.

Hadi, Muhamad S. 2019. “The Use of Song in Teaching English for Junior High School Student.” in English Language in Focus 1(2):107–112.

Harasim, Linda. 2000. “Shift happens: online education as a new paradigm in learning.” In The Internet and Higher Education 3(1-2): 41-61.

Hwu, Shiow-Lin. 2023. “Developing SAMM: A Model for Measuring Sustained Attention in Asynchronous Online Learning.” Sustainability 15:9337.

Hinde, Stephen J., Smith, Tim J., Gilchrist, Ian D. 2018. “Does narrative drive dynamic attention to a prolonged stimulus?” in Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications 3(1):45-57.

Horton, Andrew. 2015. “Aristotle and Hollywood: Dramatic Structure From Ancient Greece to Avatar & Beyond.” in Journalism and Mass Communication 5(8):428-433.

Klerings, Irma., Weinhandl, Alexandra S., Thaler, Kylie J. 2015. “Information overload in healthcare: too much of a good thing?” in The Journal of Evidence and Quality in Healthcare 109(4):285-290.

Kniaź-Hunek, Lidia 2023. “The (R)evolution of Music Video in American Music Industry New Horizons.” in New Horizons in English Studies 8(8):163-176.

Kumar, Abhishek., Bachchan, Ashok K. 2023. “The Critique Of Traditional Narrative Structure And The Evolution Of Fiction In Virginia Woolf’s Modern Fiction.” in International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts 11(6):814-817

Kuzmicz, Jennifer E. 2008. “That’s ‘edutainment!’ Reflections on teaching and learning” in Canadian Family Physician 54: 257-258.

Landrum, Eric R., Brakke, Karen., McCarthy, Maureen A. 2019. “The Pedagogical Power of Storytelling.” in Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology 5(3):247–253.

Leavitt, Jonathan D., Christenfeld, Nicolas JS. 2011. “Story spoilers don’t spoil stories.” Psychological Science (22):1152–1154.

Loucky, John P. 2008. “Reassessing the Educational Works and Contributions of Comenius to the Development of Modern Education.” in Bulletin of Southwest Women’s College 12:149-163.

Ma, Lin. 2022. “Research on the effect of different types of short music videos on viewers’ psychological emotions.” in Frontiers in Public Health 10:992200.

MacWhinney, Brian. 2015. “Language development.” in Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Vol. 2. Cognitive processes, edited by Lynn Liben and Ulrich Müller, 296–338. New York, NY: Wiley.

Masters, Kenneth., Gibbs, Trevor. 2007. “The Spiral Curriculum: implications for online learning” in BMC Medical Education 21(7):52-62.

Mou, Tsai-Yun., Jeng, Tay-Sheng., Chen, Chien-Hsu. 2013. “From storyboard to story: Animation content development.” in Educational Research and Reviews 8(13):1032-1047.

Nalabandian, Taleen., Ireland, Molly E. 2019. “Genre-typical narrative arcs in films are less appealing to lay audiences and professional film critics.” Behavior Research Methods 51:1636–1650.

Ngong, Paul A. 2020. “Music and sound in documentary film communication: An exploration of Une Affaire de Nègres and Chef!” in CINEJ Cinema Journal 8.1:156-184.

Nikulina O, van Riel ACR, Lemmink JGAM, Grewal D, Wetzels M (2024). Narrate, Act, and Resonate to Tell a Visual Story: A Systematic Review of How Images Transport Viewers, Journal of Advertising, 53(4):605-625.

Nitkin, Karen. 2018. “Johns Hopkins Medical Education Goes Digital.” Johns Hopkins University. September 12. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/articles/johns-hopkins-medical-education-goes-digital

NPR’s Skunk Bear. A Neuroscience Love Song. [music video] American Public Broadcasting, 2015.

Nunez, Roland. 2020. “Development and Assessment Strategies of Educational Entertainment Media for Learner-Centered Instruction.” in Higher Education Technology and Higher Education 1(1):87-103.

Okan, Zuhal. 2003. “Edutainment: is learning at risk?” in British Journal of Educational Technology 34(3):255-264.

Ottowitz, William E. 2024. “Innovations in Medical Education: Successful Alpha Phase Testing of the ‘Limbic Circuitry’ Augmented Didactics Cell Phone APP.” Oral communication presented at the Bett UK ExCeL Education Technology Conference, London, UK. January 25, 2024.

Ottowitz, Wiliam E., Moore, Michael., Brook, Nilly., LaFrance, William C. 2023. “The Double Narrative, HEMVFED Genre, and Augmented Didactics Platform: A Synthesis in Progress.” Abstract presented at the USC Innovations in Medical Education Conference XX, Los Angeles, CA, February 17.

Ottowitz, William E. 2022. “An Unconventional Hybrid Documentary Format for Medical Edutainment: A Preliminary Survey.” Abstract presented at the USC Innovations in Medical Education Conference XIX Los Angeles, CA, February 17.

Ottowitz, William E. 2021. Components, Formative Development, and External Critique of a Novel Music Video Formatted Framework for Brain Science and Neuropsychological Education: The Didactic Relevance of a VFX Driven Narrative. master’s thesis, University of the

Arts, London. available at https://19003419-vfx.weebly.com/thesis.html

Ottowitz, William E. 2020. “Brain Waves from Outer Space,” YouTube video, 8:19. December 31, 2020. available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vE-yW2Ea eHk

Rauscher, Francis H., Shaw, Gordon L., Ky, Katherine N. 1993. “Music and spatial task performance.” in Nature. 365: 611.

Romaniello, A., Chircu, A. 2018. “A Connected World: A Systematic Literature Review of the Internet Effects on Society.” in Issues in Information Systems 19(3):110-119.

Rueda, Marta M., Cerero, José F., Cerero, Daniel F., Menese, Eloy L. (2024). “Perspectives on online learning: Advantages and challenges in higher education.” In Contemporary Educational Technology 16(4): ep525.

Schindler, Laura A., Burkholder, Gary J., Morad Osama A., Marsh, Craig. 2017. “Computer-based technology and student engagement: A critical review of the literature: Revista de universidad y sociedad del conocimiento.” in International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 14:1-28.

Seeman, Joshua. 2017. Benefits of Nonlinear Storytelling in Film and Television. Honors Thesis, California State University, Long Beach.

Shaffer, Victoria A., Focella, Elizabeth S., Hathaway, Andrew., Scherer, Laura D., Zikmund-Fisher, Brian J. 2018. “On the Usefulness of Narratives: An Interdisciplinary Review and Theoretical Model.” in Annals of Behavioral Medicine 52:429–442.

Sharif I., Wills, Thomas A., Sargent, James D. 2010. “Effect of Visual Media Use on School Performance: A Prospective Study.” in Journal of Adolescent Health 46(1):1-18.

Sukhera, Javeed. 2022. “Narrative Reviews in Medical Education: Key Steps for Researchers” in Journal of Graduate Medical Education August, 418-419.

The Buggles. Video Killed the Radio Star [music video]. Island Records, 1979.

Tobin, Rob. 2016. “Story Structure: The Four Act Structure.” Screenwriting How-To Articles (blog). Script Magazine. February 9. https://scriptmag.com/features/the-four-act-structure

Trapp, Michael. 1996. “Tragedy and the Fragility of Moral Reasoning: Response to Foley.” in Tragedy and the Tragic: Greek Theatre and Beyond. edited by Michael S Silk, 74-84. Oxford Publishers.

Tze, Virginia M.C., Daniels, Lia M., Klassen, Robert M. 2016. “Evaluating the Relationship Between Boredom and Academic Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis.” in Educational Psychology Review 28:119–144.

Velleman, David J. 2003. “Narrative explanation.” in Philos Rev 112(1):1–25.

Vinovskis, Maris A. 1987. “Family and Schooling in Colonial and Nineteenth-Century America.” in Journal of Family History 12(1-3):19-37.

Wang, Shih-Tse., Tang, Yao-Chien. 2021. “How narrative transportation in movies affects audiences’ positive word-of-mouth: The mediating role of emotion.” in PLoS ONE 16(11):1-13.

Watts, Judy., Hubner, Austin., Pei, Jun., Coelho, Michaela B. 2025. “Is it safe? The effect of narrative vs. non-narrative messages on story-related knowledge of medicated abortion.” in Frontiers in Communication 10:1-14.

Wolfe, Michael BW. 2005. “Memory for narrative and expository text: independent influences of semantic associations and text organization.” in Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, memory, and cognition 31(2):359–364.

Wolfe, Michael BW., Mienko, Joseph A. 2007. “Learning and memory of factual content from narrative and expository text.” in British Journal of Educational Psychology 77(3):541–564.

Yip DKM. 2023. “XR Is More Than the Sum of AR, VR and MR”. in Human Factors in Communication of Design, (90):82–88.

Yoonmi, Kim. 2021. “Worldwide Story Structures.” Kim Yoonmi Author (blog). February 1. https://kimyoonmiauthor.com/post/641948278831874048/worldwide-story-structures

Zaini, Nur S.H.B., Yusoff, N. 2024. “Exploring the interplay of narrative in music videos and its influence on listeners’ experience.” In Journal of Creative Arts 1(2):69-87.