Abstract

Aurélio da Paz dos Reis, a pioneer in early Portuguese cinema, explored cinematic technologies before turning to photography. Paz dos Reis, who introduced cinema to Portugal in 1896 with Saída do Pessoal Operário da Fábrica Confiança, later switched to stereoscopic photography, leaving behind a remarkable archive of 7,294 glass plates showcasing his technical innovation and aesthetic originality.

As an amateur photographer, Paz dos Reis created a large stereoscopic collection of portraits, landscapes, and everyday scenes. He photographed both documentary and artistic subjects, following his era’s visual trends.

Numerous panoramic photographs explored the genre’s depth and three-dimensionality. These images preserve late 19th- and early 20th-century Portuguese society visually.

His use of panoramic view cards showed the Mackenstein jumelle stéréopanoramique camera’s versatility. By moving one lens and removing the internal divider, this device allowed stereoscopic and panoramic photography. Due to its duality, it could switch between visual modes easily.

Paz dos Reis studied monocular and stereoscopic vision. Unlike stereoscopic portraits, panoramic portraits align subjects perpendicularly to the camera. The panoramic approach made stereoscopy more natural-looking.

Panning paintings and engravings from the 18th and 19th centuries depicted vast landscapes and urban scenes with immersive visual effects. Since photography made these compositions portable and accessible, they fit stereoscopic formats.

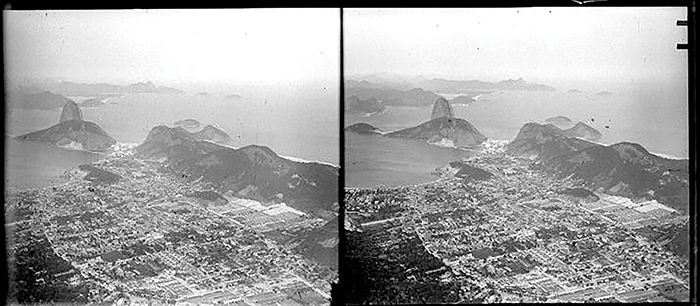

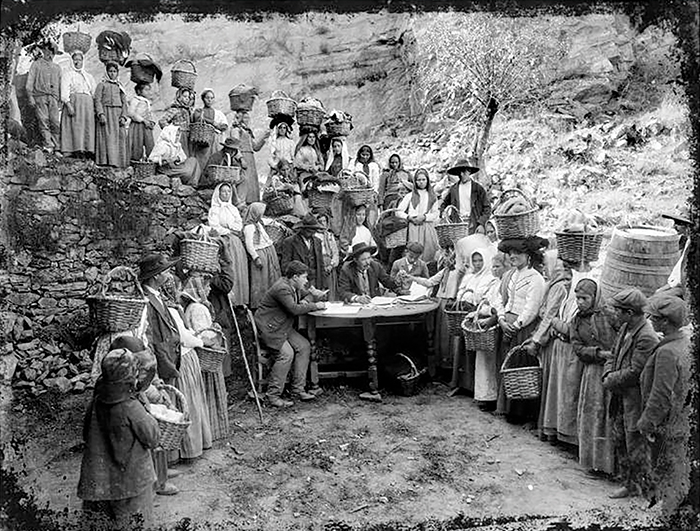

Through panoramic and stereoscopic imaging, depth perception can be understood. Paz dos Reis photographed familial and social events in Nova Cintra, including Paris (1900) and Rio de Janeiro (1909). His panoramic views, especially for group portraits, show his interest in human groups and public gatherings, expanding stereoscopy’s expressive potential.

Keywords: Stereoscopy, Aurélio da Paz dos Reis, Media archaeology, Panoramic stereoscopy, Panorama.

1. Introduction: Aurélio da Paz dos Reis and the Origins of Portuguese Cinema

In the early 20th century, Portuguese photographer and filmmaker Aurélio da Paz dos Reis (1862–1931) utilized a diverse array of visual technologies that connected intimate domestic portraits with expansive panoramic vistas. Paz dos Reis, recognized as Portugal’s inaugural cinematographer, is also notable for his stereoscopic photography, an underappreciated yet crucial aspect of his career. His work elucidates the intersections of spectacle, technology, and cultural identity amid a period of rapid visual transformation.

This article analyzes the role of stereoscopic and panoramic imagery as both documentation tools and immersive experiences that foreshadowed contemporary media spectatorship. The article examines Paz dos Reis’s stereoscopic compositions, highlighting their role in mediating personal memory and national narrative, private life and public spectacle, as well as stillness and movement.

2. Early Cinema in Portugal

Cinema was introduced to Portugal in 1896 by Aurélio da Paz dos Reis, who is widely acknowledged as the founder of Portuguese cinema. He directed the inaugural Portuguese films featuring national themes, particularly Saída do pessoal operário da Fábrica Confiança (“Exit of the Factory Workers from the Confiança Factory”), regarded as a seminal work of early local cinema (Penafria 2013).1

Paz dos Reis’s work lacks genuine cinematic experimentation; rather, cinema was promptly designated a function—to facilitate the dissemination and preservation of Portuguese cultural heritage. His documentaries depict national cultural motifs, including markets, street scenes, and traditional dances, framing cinema as a medium for cultural representation rather than artistic expression. (Roque 2021).

His objective was unequivocal: to utilize moving images to advocate for Portuguese life and culture internationally, particularly in Brazil, where he aspired to forge a commercial alliance. Nevertheless, the agreement collapsed, and the capital invested in equipment and production was never recouped (Costa 1978). Like Edison and even the Lumière brothers and Paz dos Reis may have initially undervalued the enduring profitability of cinema. Nonetheless, he commenced filming vignettes of quotidian Portuguese life, establishing a cinematic approach focused on cultural documentation.

3. From Cinema to Photography: A Shift in Practice

After the failure of his cinematic venture, Paz dos Reis gradually redirected his attention to photography, engaging with the medium with revitalized intent. His career aligned with Porto’s industrial expansion in the 1880s, a period marked by the proliferation of photography studios, increased capital concentration, and the widespread popularity of themed photographic albums (Resende 2021). By 1881, studios like União and Biel dominated the market, establishing a visual language that was both commercially viable and culturally ingrained.

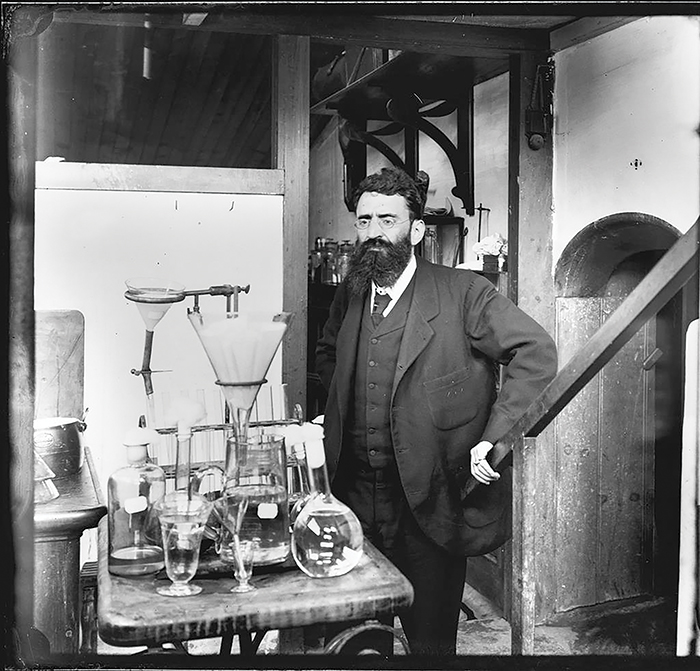

Alongside his film endeavors, Paz dos Reis became profoundly involved in stereoscopic photography3, capturing images of monuments, landscapes, and regional traditions in northern Portugal.4

A dedicated republican, he participated in the political conflicts that culminated in the 1910 declaration of the Portuguese Republic.

In 1899, during the bubonic plague outbreak in Porto, he created a visual documentation that stands as one of the few extant photographic records of the epidemic.5

His legacy, therefore, extends from the urban street photographer to the pioneer of Portuguese cinema, providing an unmatched visual documentation of the social, cultural, and political life of his era.6

This novel medium enabled him to enhance his visual strategies, particularly regarding his treatment of space, perception, and social experience.

4. Themes and Visual Techniques in the Works of Aurélio da Paz dos Reis

Drawing from his early cinematic experiences and stereoscopic experiments, Paz dos Reis developed a visual language that profoundly impacted modern Portuguese visual culture. His oeuvre encompasses cinema, stereoscopy, press photography, and portraiture, each enhancing the comprehension of technological advancement, documentary methodology, and symbolic visual communication during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

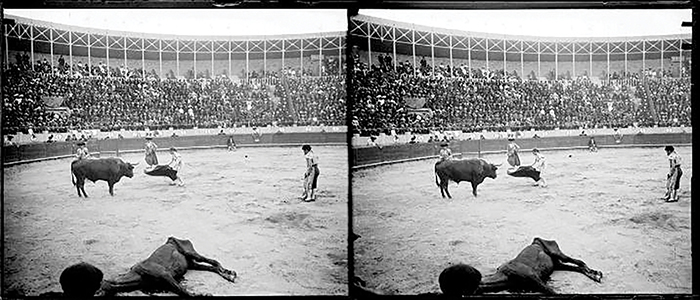

Stereoscopic photography emerged as a key visual strategy—more than a technical exercise, it immersed viewers in daily life, public events, and cultural

rituals. Paz dos Reis aligned technological form and cultural intention to create emotionally resonant, immersive “tableaux”.7

4.1 Estereoscopio Portuguez10: A Commercial Vision

Recognized as “the best example of this industrial reality” in Portugal (Peixoto 2017), Paz dos Reis actively commercialized his stereoscopic photographs under the brand Estereoscopio Portuguez, operating from his shop in Porto. His collection, now housed at the Portuguese Centre of Photography, includes more than 7,200 stereoscopic photographs in diverse formats: negatives, positives, printed on cardboard, and transparent paper.11

This industrial paradigm of image creation and dissemination indicates an initial convergence of media production and capitalist ventures, positioning Paz dos Reis within a wider European trend of commodified visual culture. His visual practice both documented national identity and engaged in the burgeoning market of visual consumption.

Aurélio da Paz dos Reis frequented Paris multiple times, actively engaged in the dynamic social milieu of his era, and exhibited an inquisitive intellect. His intrigue with innovative inventions convinced him that animated photographs represented a novelty with significant potential for success (Costa 1978).12

An exemplary instance of architectural and symbolic photography is evident in his Paris series from the 1900 Universal Exhibition. An elevated, axial perspective showcases a significant footbridge and domed pavilion, illustrating the stereoscopic ability to convey both spatial depth and national magnificence. A rare nocturnal photograph of the Eiffel Tower—illuminated by artificial light—serves as further evidence of his technical proficiency, attaining tonal clarity under extreme exposure circumstances.

Paz dos Reis, in addition to his work in Paris (1900), also captured photographs of Rio de Janeiro in 1909, establishing himself as a pivotal figure in the propagation of stereoscopic imagery in both Portugal and Brazil. He significantly influenced the consumption and experience of stereoscopic photographs and viewing devices through their commercial distribution.

4.2 Press Photography and Visual Journalism

Aurélio da Paz dos Reis significantly contributed to the advancement of visual language in the Portuguese press, transcending stereoscopy. During an era characterized by pervasive illiteracy, photography emerged as an essential communicative instrument, adept at conveying journalistic information visually and efficiently. His contributions coincided with the emergence of the illustrated press, which aimed to modernize public discourse and amplify narrative impact through visual representation.

Grácio (2012) designates Paz dos Reis as a member of the inaugural generation of Portuguese photojournalists, alongside notable individuals such as Joshua Benoliel, António Novaes, and Arnaldo Fonseca. This innovative collective established the visual syntax of early photojournalism, merging aesthetic sensibility with a dedication to documenting socially pertinent events.17

Grácio notes that Paz dos Reis “contributed to the development of contemporary visual language in journalism, distinguished by his capacity to capture pivotal moments and communicate information through photography.” His images served not only as illustrations but as semiotic entities capable of conveying intricate narratives independently of textual elucidation.

4.3 Postcards, Portraits, and the Mediation of Identity

Postcards produced by Aurélio da Paz dos Reis provide a distinctive insight into the visual interplay between territory and identity in early 20th-century Portugal. Beyond mere personal keepsakes, these meticulously arranged, and stereoscopically enhanced images functioned as instruments of collective memory.

Postcards embodied both local festivities and conveyed wider urban aesthetics and symbolic representations. A commentator observes that “the fixed image of the postcard reveals a symbolic aesthetic of the city,” encapsulating an idealized representation of urban life.18

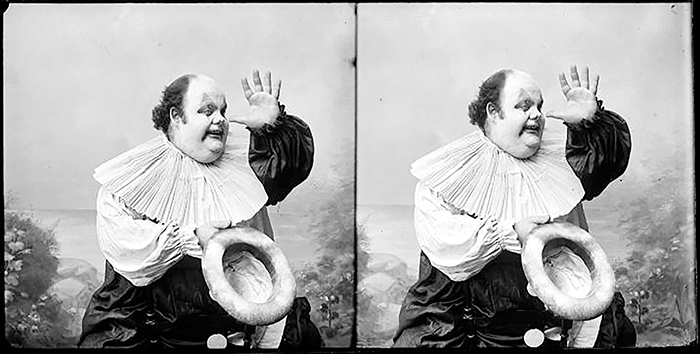

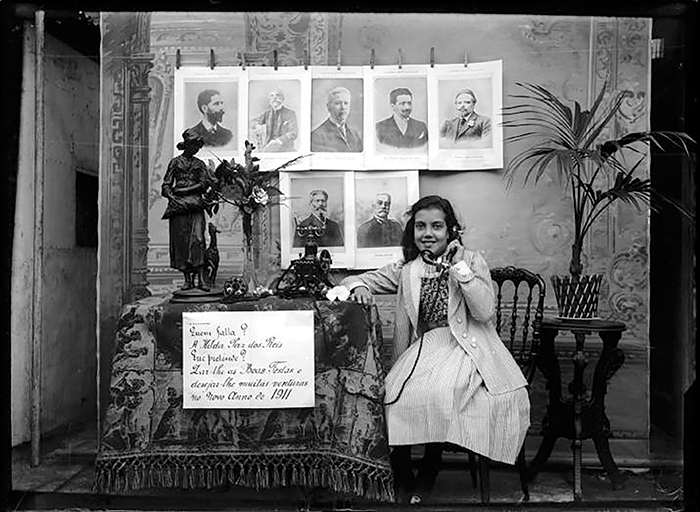

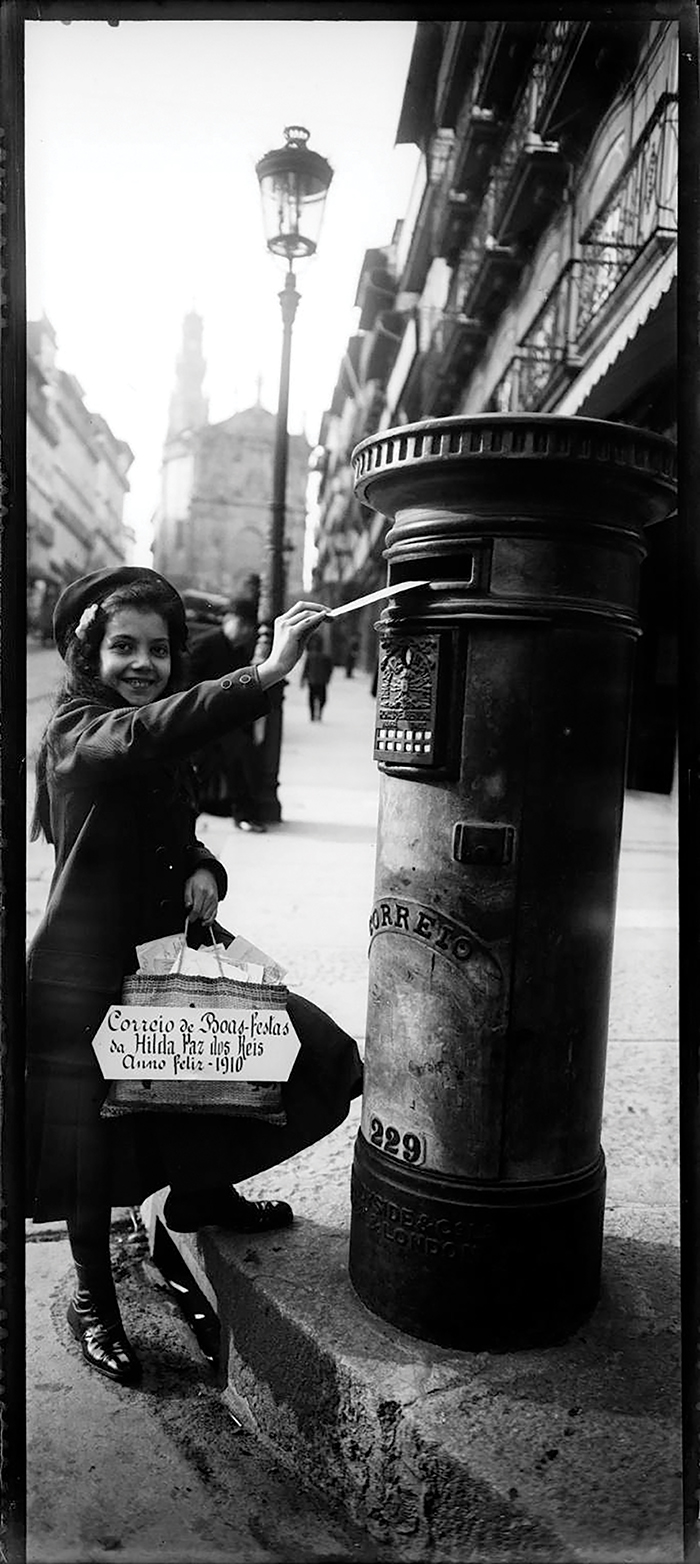

Paz dos Reis created New Year greeting cards that showcased family portraits, costumes, and studio props, frequently incorporating his youngest daughter, Hilda. The images were carefully created with a stereoscopic camera, showcasing a blend of personal expression, photographic tradition, and technical innovation. They illustrate how domestic photography can function concurrently as a private ritual and a form of public communication.

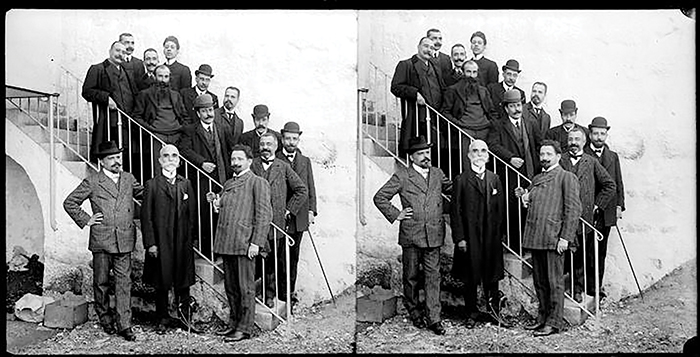

Paz dos Reis’s oeuvre encompasses a diverse thematic spectrum, including landscapes, street scenes, local customs, and portraits of actors, politicians, and celebrities in Portugal. He exhibited a distinct inclination for theatrical portraiture, creating studio images presumably intended for commercial distribution. Although these portraits possessed commercial allure, they also represent a significant visual repository.

The portrait of Lucília Simões, for example, integrates Symbolist aesthetics with the figure of Salome, invoking themes of performance, femininity, and celebrity.

Paz dos Reis interconnected private family imagery and public portraiture, merging personal memory with national identity. His photographs demonstrate a purposeful endeavor to compose, preserve, and disseminate symbolic depictions of Portuguese society. His studio portraits, whether artistic or documentary, frequently combined aesthetic sophistication with the principles of publicity, showcasing political and cultural figures. This collection of images signifies a vital convergence of personal emotion and cultural legacy.

Furthermore, Paz dos Reis actively documented the political and social transformations that culminated in the proclamation of the Portuguese Republic in 1910. As a dedicated liberal republican, he actively engaged in political conflicts and visually documented significant occurrences, including public protests, urban reforms, and the bubonic plague epidemic in Porto. His camera functioned not merely as a documentary device, but also as a political instrument—connecting ideology and visual documentation.

In the early 20th century, as stereoscopy experienced a revival in Europe, Paz dos Reis strategically transitioned to photography, perceiving it as a more stable and lucrative endeavor than cinema. He marketed stereoscopic images at his flower shop in Porto, merging commerce and image production in a manner that persisted until his demise in 1931. His photographic legacy, comprising family portraits, public events, and symbolic compositions, represents one of the most extensive stereoscopic collections in the Portuguese public archives today.

4.4 From Intimacy to Immersion: Panoramic Vision and the “Effect of Presence”

In addition to his personal studio portraits and domestic postcards, Aurélio da Paz dos Reis also focused his lens on the collective experiences of modernity. His panoramic and stereoscopic images aim not only to document public life but also to engage the viewer, transforming them into participants in a more expansive visual experience. This aesthetic and technological transformation was supported by a century of optical and photographic advancements that broadened the limits of visual representation.

The following are significant milestones that facilitated this evolution, situated Paz dos Reis’s practice within a wider historical context.

By the 1900s, a century of optical advancements had prepared Paz dos Reis to fully exploit stereoscopic and panoramic techniques.22

Paz dos Reis’s photographic practice progressively adopted immersive techniques that transcended private portraiture and solitary documentation. These advancements resulted in his panoramic and stereoscopic compositions, which aimed not only to document events but to immerse the viewer in the visual field—facilitating a profound investigation of spatial experience and emotional presence.

Panoramic stereoscopic photography represents the pinnacle of Aurélio da Paz dos Reis’s immersive aspirations. These images—produced for touristic, educational, and commemorative objectives—did more than document events: they engaged the viewer in the scene, eliciting what scholars refer to as the effect of presence. The feeling of closeness depended not only on content but also on formal composition: wide-angle framing, frontal alignment, layered depth, and meticulous detail combined to create spaces that appear both concrete and occupied.

Crowd scenes most clearly exemplify this immersive effect. According to Flores, the individuals depicted in these group portraits “populate and appear to emerge from his images,” transforming into “agents of history.” These compositions, typically arranged frontally with limited depth, resemble theatrical tableaux—harmonizing documentary realism with artistic purpose. Their visual grammar, “broader than profound,” fosters a multi-layered temporality in which presence, memory, and historical awareness intersect.

5. Mackenstein and the Aesthetics of Flexibility

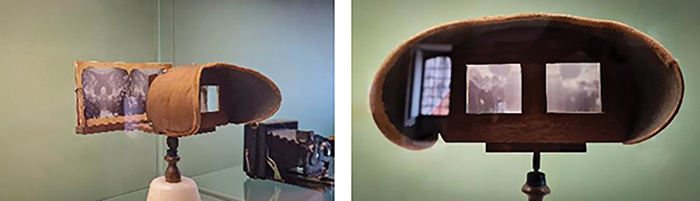

This immersive vision was primarily facilitated by one instrument: the Mackenstein jumelle stéréopanoramique camera, produced in Paris at the turn of the 20th century. The model employed by Paz dos Reis—presumably the La Francia, designed for 6×13 cm glass plates—facilitated effortless transitions between stereoscopic and panoramic modes. By repositioning one lens to the center and eliminating an internal divider, the photographer could alternate between six stereo pairs and six panoramic images. The camera included Carl Zeiss lenses (f:1.8/110 mm), a collapsible sports viewfinder, and a sturdy leather-clad wooden body—compact, sophisticated, and suitable for field application.

The dual functionality afforded Paz dos Reis remarkable visual versatility: the same device facilitated both intimate stereoscopic portraits and expansive street scenes, allowing for technical precision and creative flexibility.30

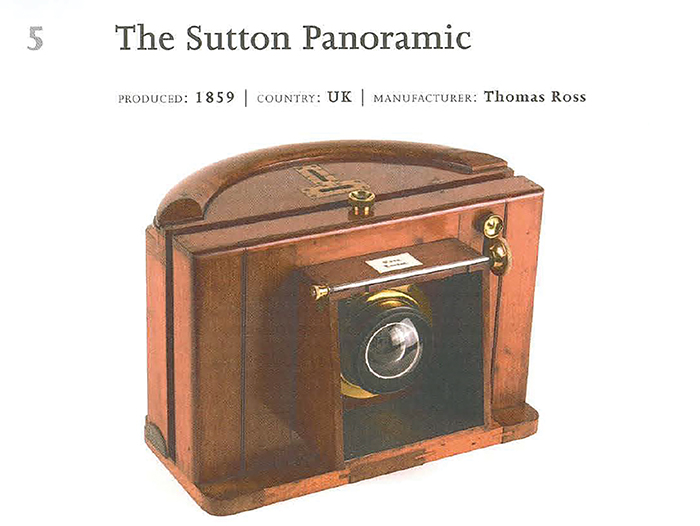

5.1 Sutton’s Lens and the Prehistoric Context of Immersion

Paz dos Reis’s panoramic aspirations also reflect prior optical advancements, notably Thomas Sutton’s 1859 water-filled hemispherical lens, which recorded 120° fields of view. Despite being separated by decades, both Sutton and Paz dos Reis exhibited a desire to redefine space and presence through visual media.31

By integrating the immersive optics of Sutton with the portable dual-mode capabilities of Mackenstein, Paz dos Reis successfully generated images that were both historically significant and sensorially immediate. His photographs provide a tangible sensation of presence: amidst the crowd, at the ceremony, and within the domestic ritual.

They are not merely passive documents; they serve as instruments of visual presence. Within that presence resides both their technological accomplishment and cultural heritage.

Paz dos Reis’s panoramic stereoscopic photography exemplifies a pinnacle of early 20th-century visual experimentation, yet it is profoundly anchored in a more extensive history of optical innovation and widespread intrigue with three-dimensional imagery. Comprehending these historical precedents is crucial for understanding the conceptual and technological underpinnings of his media practice.

To comprehend the immersive aspirations of Paz dos Reis’s photography, one must consider the extensive cultural and technological history of stereoscopy. These immersive techniques did not arise in isolation; they are rooted in a longstanding lineage of stereoscopic innovation, which will be examined in the subsequent section.

6. Origins of Stereoscopy: Visual Technology and Cultural Enthusiasm

To comprehend the origins of this immersive visual logic, we must revisit the extensive historical lineage of stereoscopic technology and perception. Aurélio

da Paz dos Reis’s photographic methods were intricately linked to an extensive history of stereoscopic experimentation that commenced in the early 19th century and reached its zenith during the Golden Age of Stereoscopy. His ability to create immersive, three-dimensional, panoramic visual narratives was developed over decades of optical innovation, public interest, and industrial advancement.

6.1 Origins of Stereoscopy

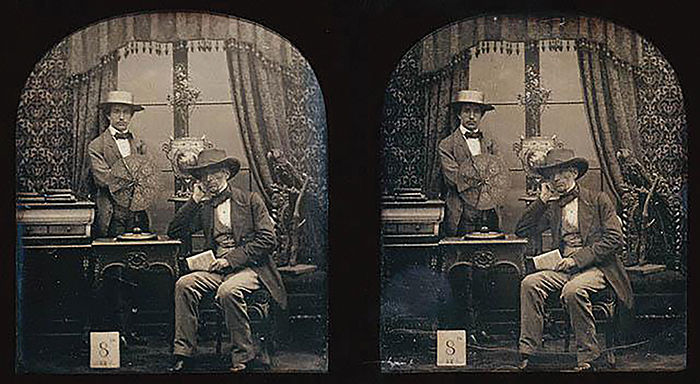

The first conceptual breakthrough occurred in 1838, when Charles Wheatstone presented his stereoscopic research to the Royal College of London. Wheatstone illustrated the principle of binocular vision by employing angled mirrors to project distinct images to each eye, thereby demonstrating how the brain amalgamates two slightly disparate images into a singular perception of depth. His stereoscope, designed by optician R. Murray, preceded the advent of photography yet established the groundwork for its subsequent incorporation into photographic media.

David Brewster, while occasionally misattributed as the inventor of the stereoscope, significantly contributed to its refinement and popularization. In 1849, he unveiled the lens-based Brewster stereoscope, which was more portable and user-friendly than Wheatstone’s initial design. Brewster collaborated with French optician Jules Duboscq to disseminate stereoscopic daguerreotypes, including the renowned image of Queen Victoria displayed at the Great Exhibition of 1851. This public event elevated stereoscopy to a widespread cultural phenomenon across Europe.

6.2 Mass Production and Widespread Attraction

The advent of the wet collodion process in the 1850s facilitated the mass production of stereoscopic images. Companies like the London Stereoscopic Company (established in 1854) promoted stereoscopes with the slogan “No home without a stereoscope,” highlighting their widespread cultural significance and allure among the Victorian middle class. By the 1860s, stereoscopic viewing had evolved into a conventional domestic activity, fulfilling educational, documentary, and moral purposes.

Between 1857 and 1864, photographers and publishers such as Furne and Tournier produced approximately 7,000 stereoscopic cards, documenting landscapes, monuments, and social life across Europe. Their images, disseminated extensively, are likely to influence viewers like Paz dos Reis, whose stereoscopic creations echo these earlier models in style and ambition.

Nineteenth-century stereographers explored motion effects, connecting photography and cinema.35 These experiments indicate that the cinematic impulse predated cinema and likely influenced Paz dos Reis’s hybrid sensibility across various media.

6.3 Technological Innovations and Persistent Popularity

Stereoscopy underwent multiple resurgences during its history, notably in the 1850s, 1900s, 1930s, 1950s, and the 1980s. Each revival was propelled by technological advancements and transformations in visual culture. In the late 19th century, portable wooden stereo cameras, including those created by John H. Powell (1858), broadened accessibility to the format. The introduction of dry plates in the 1880s and roll film in the 1890s significantly transformed production, providing enhanced convenience and portability (Pritchard 2015).

The advancements culminated in the development of compact stereo cameras in the 20th century, such as Fuji’s W1 and W3 models, which incorporated digital displays and printing capabilities. This continuity affirms the lasting allure of three-dimensional photography, spanning from Wheatstone’s mirror stereoscope to digital 3D imaging.

6.4 Heritage and Significance for Paz dos Reis

By the early 1900s, when Paz dos Reis embraced stereoscopy as his principal medium, he engaged in a longstanding and transnational visual tradition. His panoramic stereoscopic compositions reflect prior optical theories and visual cultures influenced by European scientists, instrument-makers, and image creators.36

Paz dos Reis, utilizing the Mackenstein camera and visual rhetoric based on depth and immersion, positioned himself within a lineage that encompasses Wheatstone’s optical experiments, Brewster’s stereoscopes, and the widespread distribution of stereoscopic cards in mid-19th century France and Britain.

7. Panoramic Stereoscopy and the Tradition of Panorama

While the relationship between panoramic stereoscopic photography and the 19th-century panorama is not strictly linear, a notable genealogical continuity exists between them. Both possess a unified visual objective: to broaden the viewer’s perceptual scope and amplify the experience of presence. Through the grand architecture of a rotunda or the optical accuracy of stereoscopic lenses, these traditions sought to captivate audiences in immersive manners—approaches that were both aesthetic and ideological.

7.1 From Rotundas to Stereocards: A Comparison of Immersive Strategies

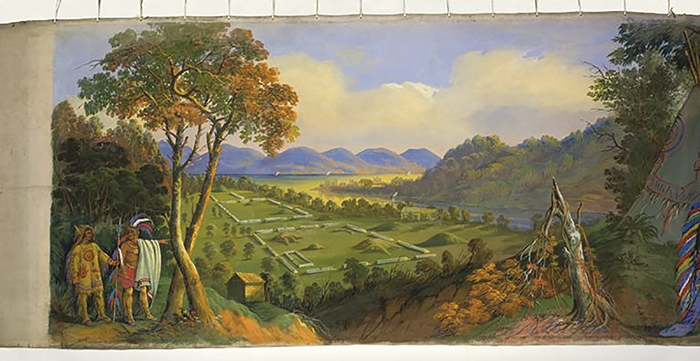

The panorama, conceived by Robert Barker in 1787, presented 360-degree painted vistas displayed in circular structures. These rotundas positioned the observer at the core of a perpetual, immersive image—frequently augmented with architectural elements and atmospheric illumination. According to Oettermann (1997), panoramas constituted the inaugural mass visual medium that could generate entirely immersive visual experiences. They combined painting, architecture, and exhibition techniques to evoke wonder, frequently in support of nationalist, imperial, or scientific narratives.

Panoramic stereoscopic photography emerged a century later, transforming these immersive aspirations into a more compact and portable format. Rather than utilizing architectural scale, it depended on binocular depth and photographic realism to create the “effect of presence.” This more intimate and accessible mode of visual immersion continued to rely on analogous perceptual principles, emphasizing spatial extension, emotional resonance, and embodied engagement of the audience.

In diverse national contexts, panoramas fulfilled distinct ideological and educational purposes.38

Collectively, these national instances demonstrate that the panorama tradition served not merely as spectacle but also as a vehicle for ideological development and cultural education.

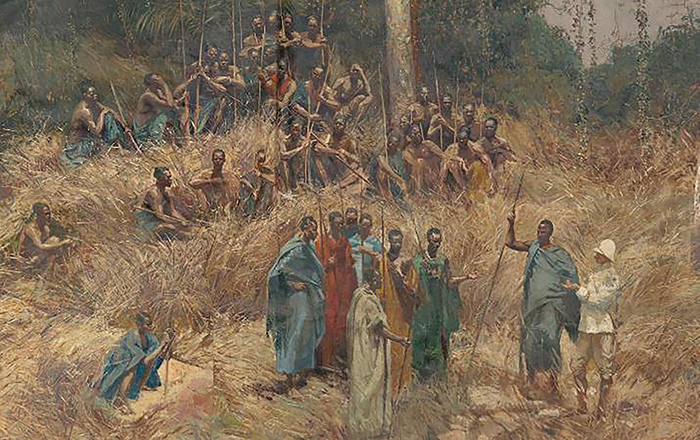

7.2 Virtual Art and Ideological Immersion

Oliver Grau posits that the 19th-century panorama serves as a precursor to virtual reality. It elicited emotional reactions and ideological conformity through immersive visual techniques that immersed the viewer in a fabricated reality.39

This emotive reasoning—anchored in spectacle and subservience—echoes in the stereoscopic photographs of Paz dos Reis, especially those depicting crowds, ceremonies, or political occurrences. These images generate both documentation and engagement: viewers are encouraged to experience, rather than merely observe.

7.3 Visual Discipline and the Modern Observer

Jonathan Crary (1992) contextualizes the panorama within a wider 19th-century transformation in visuality—from classical models of perception to fragmented ones, physiological modes aligned with modern optical media. He contends that the panorama offered a uniform visual landscape in which the observer experienced both autonomy and disembodiment, a phenomenon further enhanced by architectural and optical arrangements.40

Stereoscopy, though appearing limited in scope, expanded this visual rationale. It concentrated on the viewer’s gaze, organized attention, and reconfigured subjectivity via immersive framing. In this regard, it functioned not merely as entertainment or education, but also as a disciplinary mechanism—an optical technology that influenced contemporary perceptual practices.

This immersive vision model has regained significance in modern contexts. Panoramic formats have been revitalized via virtual reconstructions of historical edifices, immersive museum installations, and digital simulations that replicate the nineteenth-century aspiration for comprehensive visual environments. Modern iterations of the panorama, whether via 360-degree projections or VR headsets, continue to captivate audiences by replicating its original efficacy: creating presence, directing attention, and altering the spatial perception of reality.

7.4 From Monumental Spectacle to Portable Immersion

By situating Aurélio da Paz dos Reis’s panoramic stereoscopic photographs within this extensive visual lineage, we can more effectively comprehend how his imagery transformed immersive techniques for novel technological and cultural contexts. His images do not merely document external reality; they reinterpret it as accessible and ideologically significant.

This shift—from monumental spectacle to portable immersion—illustrates a historical convergence between 19th-century panoramas and early 20th-century stereoscopic photography.44 Paz dos Reis emerges as both a documentarian and a visual strategist, converting extensive perceptual aspirations into portable media experiences.

8. Conclusion: The Historical Legacy of Paz dos Reis

Aurélio da Paz dos Reis holds a unique position in the realm of early Portuguese visual media. His contributions to cinema, stereoscopy, journalism, and cultural documentation exemplify a unified vision where technological advancement intersects with civic responsibility. Utilizing stereoscopic and panoramic compositions, he created perceptual experiences that were intimate, immersive, and historically significant.

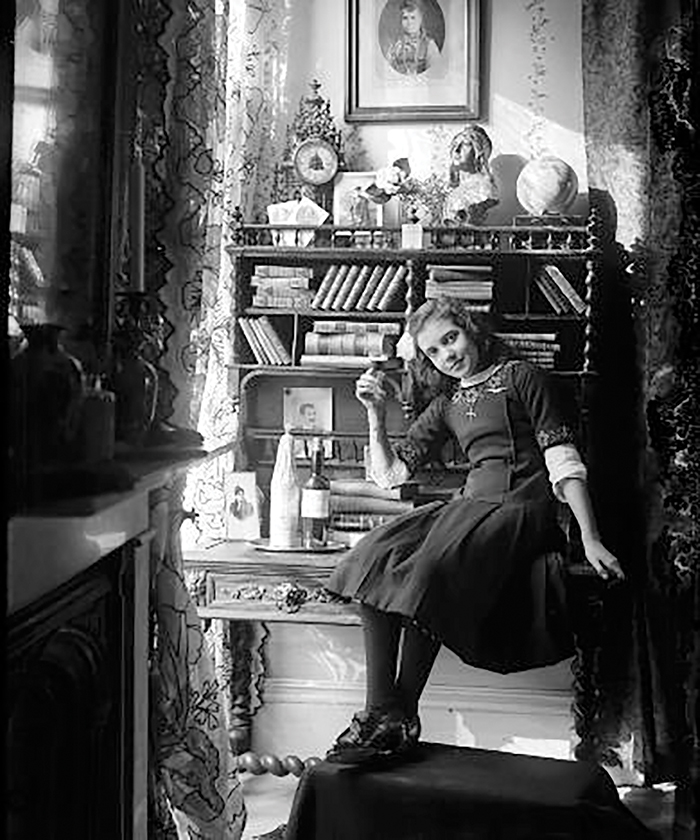

Among these, The Photography of Hilda Ophelia (1908) is distinguished by its symbolic and conceptual richness. The image, showcasing his daughter amidst symbolic props, converts a family portrait into a dialectical representation, where elements of national history intersect within a moment of staged intimacy.45

This photograph acts as the conceptual foundation for an upcoming historical documentary that revitalizes his archive through the perspective of media archaeology. This project aims to analyze early stereoscopic media as time capsules that evoke emotion, document experiences, and encourage reinterpretation.

Restoring this corpus transcends mere historical restoration. It asserts that early immersive media foresaw digital visuality and that the principles of presence and memory are ingrained in both analogue and digital cultures. The legacy of Paz dos Reis provides a significant perspective for reevaluating the interconnections between vision, technology, and cultural memory in contemporary Portugal.

Aurélio da Paz dos Reis’s stereoscopic work embodies the intersection of technological advancement, artistic inquiry, and civic creativity. His capacity to integrate formal experimentation with cultural documentation resulted in one of the most important Portuguese stereoscopic archives of the early 20th century. This visual legacy prompts historical reflection and provides a basis for current discussions on media archaeology, immersive visuality, and the politics of image creation. Housed in public institutions like the Portuguese Cinematheque and the Centro Português de Fotografia, his stereoscopic collection continues to influence curatorial methodologies, academic inquiry,

Footnotes

1Out of 30 films Paz dos Reis made, only four have survived, along with fragments and a film camera found by cinephile Henrique Alves Costa in 1978. Early cinema was single-shot, outdoor, narrative-free, and fixed-perspective. Early screenings were seen as technical spectacles, showcasing the novelty of moving images rather than artistic experimentation.

2The symmetrical Palace backdrop is animated by two carriages. Infante D. Henrique Square, Porto’s symbol and economic center. The 19th-century Palace symbolized merchant bourgeois wealth.

3French President Émile Loubet received some of these as diplomatic gifts, highlighting his cultural diplomacy.

4French President Émile Loubet received some of these as diplomatic gifts, highlighting his cultural diplomacy.

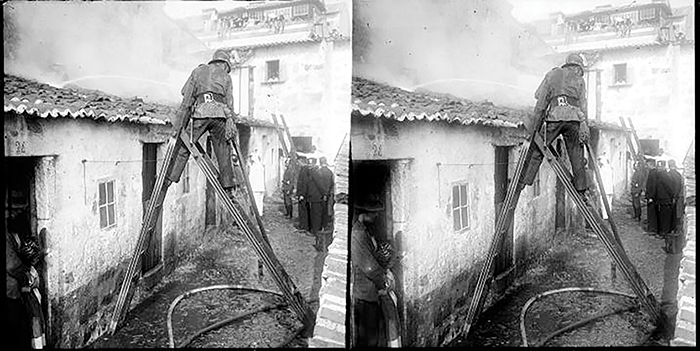

5‘[... current events’ such as the procession celebrating the centenary of India in Lisbon in 1898; doctors Ricardo Jorge, Câmara Pestana and Bento Silva in Porto during the outbreak of bubonic plague; a crowd during the siege of Porto; the fire that destroyed the Royal Theatre of São João in Praça da Batalha in 1908; a group of scientists from all over the world who came to Portugal on the occasion of the total eclipse of the sun in April 1912; photographs of the January of the steamer ‘Veronice’ stranded north of Leixões in 1913, and of flower and art exhibitions that took place in the Crystal Palace, even recording an advert of two Spaniards climbing the Clérigos Tower.’ (Peres, 1984).

6“Of all the funds and collections that the CPF holds, and of the various themes that are part of its collection, it was precisely in Aurelio’s legacy that we found the only images on a subject that arouses so much interest today - epidemics - in this case, images of the bubonic plague in Porto.” (Falcão, 2022).

7Peixoto (2017) characterizes Paz dos Reis’s stereoscopic photography as creating a “notion of visual spectacle […] eliciting feelings of wonder and admiration in the viewer” (p. 38). He contends that these images amalgamate “the spectacle of the subject with the spectacle of the medium,” unveiling a dual visual effect wherein both content and technology serve as sources of intrigue—reflective of an era when optical devices transformed perception and photography acquired cultural legitimacy as both documentation and entertainment.

8Strong spatial composition and tonal contrast add depth and drama to this stereoscopic bullfight image. A tense confrontation between the fallen bull and attentive spectators creates a striking ritual and spectacle. The static scene has theatrical energy and emotional intensity, creating an immersive visual experience.

9In this 1900 photo, the tennis net adds depth and draws attention to tennis, an elegant, aristocratic sport. Female period attire indicates social status and changing gender norms. The formal setting and audience reflect early 20th-century Portuguese high society.

10Cinema arrived in Portugal in 1896, a year after the first public screening by the Lumière brothers in Paris. Aurélio da Paz dos Reis—then a photographer and businessman based in Porto—traveled to Lyon to meet the Lumières. Despite his enthusiasm, he was informed that the cinematograph was not for sale. He then journeyed to Paris, where he acquired a similar filming device, which he later adapted and renamed “Kinematógrafo Portuguez.”

11The collection is housed at the Portuguese Centre of Photography (CPF) and includes various a variety of formats: glass plate negatives, positive prints on opaque and translucent paper, and cardboard-mounted stereoscopic cards.

12At the 1900 Exposition Aurélio da Paz dos Reis was awarded a silver medal — a remarkable achievement at the time. He later began including this distinction in his series of stereoscopic cards. Presented himself as a florist and amateur photographer, active in both countries.

13This stereoscopic image shows a grand footbridge leading to an intricately designed pavilion from an elevated axial perspective, creating a strong sense of spatial depth and three-dimensionality. The contrast between the tiny figures and massive architecture emphasizes the communal nature of the public event, while the symmetrical arrangement conveys order and grandeur. A sharp, tonal image, it documents the city and creates an immersive visual experience.

14Photographing electric lighting with clarity and precision in this rare nighttime stereoscopic photo is impressive. The Eiffel Tower’s symmetrical composition and silhouetted figures add depth and drama to a scene of modern technology, turning it into a Belle Époque celebration. Using stereoscopic photography to document electric lighting reflects the era’s modern spirit — technology recording technology.

15This stereoscopic image of Avenida Central (currently Avenida Rio Branco) exhibits sharp detail and pronounced depth, accentuated by a symmetrical composition. A prominent sculpture anchors the scene, while balanced illumination accentuates the architectural sophistication. Pedestrians and vehicles animate the Belle Époque cityscape of Rio de Janeiro. During that period, Rio de Janeiro experienced significant modernization and Europeanization, substituting colonial districts with new thoroughfares, structures, and squares.

16This panoramic photograph depicts the remarkable geography of Rio de Janeiro, featuring Sugarloaf Mountain as a focal point that juxtaposes urban density with the natural seascape. The diagonal arrangement and diffused midday illumination augment depth, eliciting a sense of equilibrium between contemporary urban expansion and the city’s striking natural landscape.

17This grammar emphasized a preference for frontal framing, natural illumination, and an emphasis on politically or socially significant scenes.

18These postcards frequently showcased Porto landmarks, including the Clérigos Tower and the Dom Luís I Bridge, portrayed from perspectives that highlighted modernity and magnificence, thereby enhancing a mythologized urban identity.

19This stereoscopic portrait of Chico Redondo exemplifies the tradition of theatrical studios. Distinguished by its technical sophistication (gelatin silver on glass), centered composition, and evocative subject, the image amalgamates documentary and performative modalities—honoring humor and spectacle as legitimate forms of cultural expression in the early 20th century.

20Technology and theater combine in this stereoscopic portrait. Delicate lighting and exposure highlight textures and create a refined, intimate atmosphere. Symbolist and Decadent influences evoke Salome and early 20th-century theatrical portraiture in the recumbent posture, intricate clothing, and stylized environment. Lucília’s playful nature balanced the sensual undertone, while the image’s vivid contrasts and stereoscopic depth created a cinematic feel.

21Republican leaders in a three-plane layout, with Guerra Junqueiro positioned at the center, representing the connection between culture and politics. The formal structure and profundity emphasize its dual function as both a documentary record and an aesthetic creation.

Three years before the 1910 Republican Revolution: Afonso Costa, a proponent of Church-State separation; Bernardino Machado, a future President of the Republic; José António de Almeida, a physician and political leader; and Guerra Junqueiro, a poet, essayist, and outspoken regime critic, were republican figures and participated in constitutional monarchy parliamentary affairs. Battle Junqueiro’s residence was a political and cultural salon, and Aurélio da Paz dos Reis’s photo captures a “backstage image of the Republic.”

22Significant advancements in 19th-century photography encompass: the daguerreotype (Daguerre, 1839), which generated singular images on silvered copper plates; the calotype (Talbot, 1841), facilitating paper negatives and reproducibility; the wet collodion process (Archer, 1851), providing sharper glass negatives; the extensive utilization of collodion for both studio and field applications during the 1850s; the creation of gelatin silver bromide dry plates (Maddox, 1871), permitting deferred development; the emergence of portable cameras in the 1880s, which democratized photography for amateurs; and ultimately, the popularization of stereoscopy in the 1890s via the introduction of dual-lens cameras.

23This photograph utilizes a static, frontal composition to depict a formally arranged group beside a train—representing modernity and movement. The intricate depth and direct gazes highlight the artificial nature of the image, merging documentary and symbolic elements.

24The image achieves spatial depth through its stereoscopic format, structured in three visual layers: crowd, participants, and architecture. Gentle, diffused illumination guarantees clarity, exposing emotive faces and intricate environments. The symmetrical arrangement and incisive narrative framework communicate the ritual’s emotional depth and its cultural and religious importance.

25This panoramic photograph depicts a substantial assembly positioned before the Grande Hotel da Torre, organized in staggered rows that enhance depth and symmetry around the central entrance. The sophisticated garments—especially the women’s lengthy dresses and ornate hats—underscore the bourgeois nature of the event, indicating a cultured social or cultural assembly.

26This stereoscopic image presents a broad panoramic composition with distinct frontal alignment, emphasizing a substantial assembly of children. The remarkable sharpness and depth of field unveil intricate facial expressions, traditional attire, and textile patterns, all depicted with balanced exposure and visual clarity throughout the scene.

27This image distinctly illustrates the parallax effect characteristic of stereoscopic photography. The foreground figures, especially those nearest to the lens, exhibit a slight displacement between the two perspectives, whereas background elements like buildings or vegetation maintain greater stability. Gentle, uniform illumination accentuates contours without producing stark shadows, thereby enhancing the overall clarity of the three-dimensional effect.

28Personal sophistication and a symbolic backdrop define this portrait. Aurélio da Paz dos Reis is slightly off-center in the Nova Cintra Garden, surrounded by ivy-clad architecture and soft natural light that highlights his polished attitude. He looks like an Edwardian dandy, and the garden symbolizes introspection and refined taste. His forward-thinking defines him as a republican. 1910 marked the establishment of the Portuguese Republic, a time of intense change. This portrait is more than a personal image—it’s a silent staging of a man ahead of his time, positioned between nature and technology, tradition and progress.

29This image depicts a contrived yet tender family portrait, showcasing Hilda Paz dos Reis holding a handwritten New Year’s message. The photograph merges personal expression with Porto’s urban landscape, featuring the Clérigos Tower, and exemplifies early 20th-century postcard conventions.

30The Mackenstein, recipient of the Gold Medal at the 1900 Paris Exposition, epitomized contemporary photographic engineering—and in his possession, it transformed into a medium for visual narrative imbued with significant historical and emotional resonance.

31Sutton’s panoramic camera employed a curved plate and hemispherical lens to surmount the narrow-angle constraints of early lenses. In Photographic Notes (1859), he characterized this as resolving “the paramount challenge for the tourist photographer”—the incapacity to depict expansive vistas.

32Camille Silvy (1834–1910) was a French diplomat and photographer active in London from 1859, where he operated a portrait studio serving aristocratic and royal clientele. He was the first to produce cartes-de-visite in London and was also an early adopter of Thomas Sutton’s patented panoramic lens (Ross). Silvy designed his own panoramic camera and produced celebrated works such as the panoramic image of the Champs Élysées (1867). Although commercially successful, he considered himself an artist, creating landscapes, still lifes, and semi-documentary urban views.

33According to David Brewster, Mr. Elliot, an Edinburgh mathematics instructor, invented the stereoscope in 1839, before photography. Brewster proposed combining images with lenses in 1849. This created the Brewster Stereoscope, a lenticular stereoscope. The hand-held device excited Queen Victoria at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

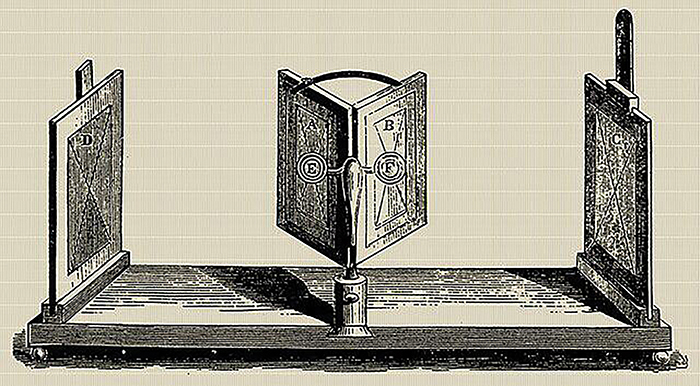

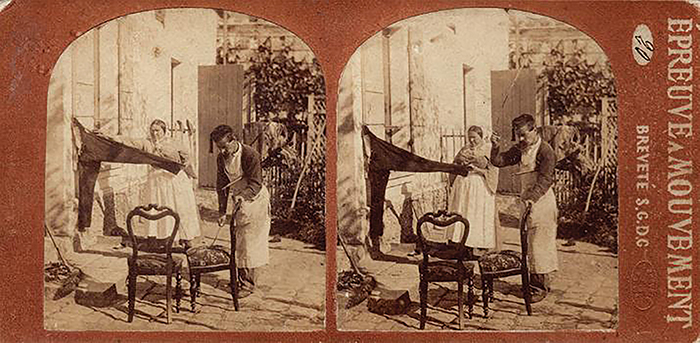

34In 1861, inspired by Claudet, Furne and Tournier published the series ‘Epréuve à Mouvement’, representing jobs with typical movements, in an initial attempt to create effects of movement in photography.

35Antoine Claudet’s 1852 stereoscopic self-portrait, where he appears smoking, is considered by Pellerin one of the earliest attempts at simulating movement within a still medium. Furne and Tournier’s Épreuve à Mouvement series (1861) further explored motion by sequencing stereoscopic variants.

36Claudet’s proto-cinematic sequences, Charles Wheatstone’s 1838 discovery of binocular depth, Brewster and Duboscq’s lens-based stereoscopes, and Furne & Tournier’s thousands of stereoscopic cards are part of this legacy These European models may have influenced Paz dos Reis’ aesthetic and technical choices.

37This image captured within the Lello Bookstore exemplifies technical precision and compositional elegance. Utilizing natural skylight and prolonged exposure, it captures intricate detail and depth, with the central staircase directing the viewer’s attention upward. The elegantly attired individuals and the opulently adorned interior enhance the scene, positioning the bookstore as a symbol of cultural distinction and intellectual ambition.

38British panoramic displays depicted urban landscapes, historical battles, and British Empire scenes, organizing urban vision and reinforcing national identity. They promoted state propaganda and civic education in France by celebrating Napoleonic victories, heroism, and patriotism. German panoramas combined beauty and education by depicting natural landscapes, archaeology, and science. To unite its multiethnic population, Austria emphasized imperial cities and military victories. In the US, panoramic views of the Mississippi River, Civil War, and Western frontier entertained and promoted nationalism and territorial expansion.

39Grau (2003) calls the panorama “the highest developed form of illusionism and suggestive power before the digital,” inducing awe and ideological alignment through perception. His Panorama of the Battle of Sedan analysis shows how immersive media affects emotions and politics.

40 According to Crary, the panorama and stereoscope isolated the viewer and focused perceptual engagement, formalizing new attention and sensation regimes. Observer Techniques, pp. 14–17.

41At first glance, Panorama of the Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Valley appears to be a single large painting of the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys. Yet, concealed behind its frame are 24 additional scenes on a long strip of fabric attached to two vertical rollers that, if completely unrolled, would occupy 2,668 square feet! John J. Egan, American (born Ireland), active mid-19th century; Panorama of the Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Valley(detail), c.1850; distemper on cotton muslin; 90 in. x 348 feet; Saint Louis Art Museum, Eliza McMillan Trust 34:1953.

42The Tirol Panorama in Innsbruck features the Innsbrucker Riesenrundgemälde, a 360-degree painting by Michael Zeno Diemer that depicts the 1809 Battle of Bergisel, a key moment in Tyrolean resistance to Napoleon. Surrounding exhibitions explore themes of identity, religion, and history. The immersive circular installation functions as both historical reconstruction and a medium for collective memory and regional pride.

43The Panorama of Congo, initially designed to showcase Belgium’s colonial successes, offers an idealized representation of the Congo while obscuring the violence of its history. Previously stored in museum reserves, it is now reevaluated as a significant colonial artifact. The CONGO-VR project (FilmEU RIT) digitally reconstructs the panorama through Virtual Reality, integrating historical research and artistic intervention to promote discourse on colonial memory. The exhibition, hosted by MUHNAC–ULISBOA, showcases works by Congolese diaspora artists and is part of wider initiatives to examine heritage and decolonial narratives.

44While rotundas housed monumental 360° painted panoramas designed for collective viewing, stereoscopic photographs offered a private but equally immersive encounter. Using binocular disparity and photographic realism, stereoscopy recreated depth perception on a miniature scale, aligning with earlier spatial logics of immersion. See Oettermann (1997) and Grau (2003).

45 The composition includes a camellia (Republican symbol), a globe, Masonic literature, Port wine bottles, a clock, and a calendar marked 1 January. This constellation of props echoes Walter Benjamin’s theory of the dialectical image, in which objects condense temporal and ideological meanings beyond literal representation (Benjamin, 1935).

References

Books

Bénard da Costa, João Mário. 1996. Paz dos Reis: The Grain and the Forest. In Aurélio da Paz dos Reis: An Exhibition. Lisbon: Cinemateca Portuguesa – Museu do Cinema.

Benjamin, Walter. 1992. The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility. In On Art, Technique, Language, and Politics. Lisbon: Relógio d’Água.

Costa, Hélder A. 1988. Long Journey to the Invention of the Cinematograph. Porto: Cineclube do Porto.

Crary, Jonathan. 1990. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Flores, Victor, ed. 2016. Porto in Relief: Stereoscopic Photography in Portugal [Digital Edition]. Lisbon: Documenta / Sistema Solar.

Flores, Victor. 2016. The Third Image: Stereoscopic Photography in Portugal. Lisbon: Documenta.

Grau, Oliver. 2003. Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Nichols, Bill. 2010. Introduction to Documentary. Translated by Sílvia Parente and José Reis. Porto: Papirus Editora.

Oettermann, Stephan. 1997. The Panorama: History of a Mass Medium. Translated by D. L. Schneider. New York: Zone Books.

Pellerin, Denis. 2021. Stereoscopy: The Dawn of 3D. Edited by Brian May. London: London Stereoscopic Company.

Pritchard, Michael. 2015. A History of Photography in 50 Cameras. London: Bloomsbury.

Resende, Nuno, Nuno Falcão, and Ana Castro. 2021. Photography: Institutions, Archives, Projects and Training. In Luísa Castro, ed., and Laura Sebastian, coord. ed. Porto: Direção Regional de Cultura do Norte – Ministério da Cultura.

Ribeiro, Fernando. 1993. Films, Figures, and Facts of Portuguese Cinema History 1896–1949. Lisbon: Cinemateca Portuguesa.

Serén, Maria do Carmo. 1998. Citizen’s Manual of Aurélio da Paz dos Reis. Porto: Centro Português de Fotografia / Ministério da Cultura.

Serén, Maria do Carmo, and Maria Teresa Siza, eds. 2001. Porto and Its Photographers. Porto: Porto Editora.

Serén, Maria do Carmo. 2010. The Photographic Image in the Perception of Space: Landscape and Urban Space in Portuguese Photography. Vila Nova de Famalicão: CITCEM.

Siza, Teresa. 1996. Aurélio da Paz dos Reis, 28 July 1862 – 19 September 1931 [Exhibition Catalogue]. Lisbon: Portuguese Commission for the Centennial of Cinema / Cinemateca Portuguesa.

Videira Santos, António. 1964. Paz dos Reis: Filmmaker, Merchant, Revolutionary. Rio Maior: Portugália Editora.

Videira Santos, António. 1990. For the History of Cinema in Portugal. Lisbon: Cinemateca Portuguesa.

Zone, Ray. 2007. Stereoscopic Cinema and the Origins of 3D Film, 1838–1952. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky.

Theses and Dissertations

Almeida, Cláudia Daniela Alves Barros Fernandes. 2017. Protagonists, Practices, and Knowledge Circulation Networks: The Dissemination of Photography in Nineteenth-Century Portugal. PhD diss., University of Évora.

Almeida, Vítor. 2015. Memory—Illusion: Formation and Continuity of the First Gaze in Cinematography. PhD diss., University of Porto.

Maschio, André Vieira. 2008. Stereoscopy: Investigation of Acquisition, Editing, and Exhibition Processes of Moving Stereoscopic Images. MA diss., São Paulo State University “Júlio de Mesquita Filho.”

Journal Articles

Aulas, Jean-Jacques, and Jean Pfend. 2000. “Louis Aimé Augustin Leprince, Inventor and Artist, Pioneer of Cinema.” Mille huit cent quatre-vingt-quinze 32: 9–74. https://doi.org/10.4000/1895.110.

Corcy, Marie-Sophie. 2009. “The Evolution of Photographic Capture Techniques (1839–1920): Revealing a Sociotechnical System.” Documents pour l’histoire des techniques 17: 57–68. https://doi.org/10.4000/dht.494.

Peixoto, Raquel. 2017. “A Certain Image of a World: Stereoscopy and Visual Education in Early 20th Century; A Study Based on the Pestalozzi Collection.” RCL – Revista de Comunicação e Linguagens 47: 34–52.

Peres, Inês M. 2020. “Photography, Science and Heritage: Photomicrography in Lisbon in the Early 20th Century.” Revelar 5. Centro Português de Fotografia.

Roque, Ricardo. 2021. “Aurélio: Photographer Citizen, Flâneur, Photojournalist?” Revelar 6. Centro Português de Fotografia.

Wade, Nicholas J. 2025. “Non-Stereoscopic Stereoscopy.” International Journal on Stereo & Immersive Media 8 (1): 4–19. https://doi.org/10.60543/ijsim.v8i1.94415.

Conference Papers

Bandeira, Maria da Saudade de Mello. 2007. “Readings of Landscape through Illustrated Postcards: Toward a Sociosemiotics of Image and Imaginary.” Paper presented at the conference Image and Thought, Museu Coleção Berardo, Lisbon, December.

Boisset, Francisco, and Stella Ibáñez. 2023. “Stereoscopic Cameras in the Francisco Boisset–Stella Ibáñez Collection.” In III Conference on Research in the History of Photography, 81–96.

Borges, Paulo A. 2016. “The Vision of the City in Marques Abreu.” Revelar, 1. IHC-FCSH, Universidade Nova de Lisboa.

Luz, Francisco C., and Raquel Peixoto. 2015. “Stereoscopic Photography of the 19th Century: Spectacle-Effect Experiences in the Origins of Photography and Cinema.” In Avanca | Cinema 2015, 28–34. Aveiro: Universidade de Aveiro / Cineclube de Avanca.

Carvalho, Daniel C. 2022. “Chronicles of the Cinematograph: João do Rio and Alberto Pimentel.” In O. Levin and G. Santos, eds., João do Rio Plural: Centennial of a Luso-Brazilian Collection, 253–271. Viveiros de Castro Editora.

Filmography

Paz dos Reis, Aurélio da, dir. 1896. Exit of the Factory Workers from the Confiança Factory. Portugal: Cinemateca Portuguesa.

Web Sources

Centro Português de Fotografia. n.d. Photographic Archive of the Collection of Aurélio da Paz dos Reis. https://digitarq.cpf.arquivos.pt/results?t=Hilda.

Cinemateca Portuguesa. n.d. Stereoscopic Photographs by Aurélio da Paz dos Reis [Inventory]. Lisbon: Cinemateca Portuguesa – Museu do Cinema.

Cunha, Pedro, and Michelle Sales, eds. 2013. Portuguese Cinema: An Essential Guide. https://www.academia.edu/5720305/Cinema_Portugu%C3%AAs_um_Guia_Essencial_2013_ed._com_Michelle_Sales.

Egan, John J. ca. 1850. Panorama of the Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Valley. Saint Louis Art Museum. https://www.slam.org/explore-the-collection/conserving-the-panorama/.

Simskultur. n.d. The Tirol Panorama with Kaiserjäger Museum. https://simskultur.eu/en/das-tirol-panorama-mit-kaiserjaegermuseum/.

Tyrol.tl. n.d. Tyrol Panorama with the Museum of the Imperial Infantry. https://www.tyrol.tl/en/highlights/museums-and-exhibitions/tyrol-panorama-with-the-museum-if-the-imperial-infantry/.

Ulusófona University – Cinema and Arts. 2023. The Congo Panorama: Unrolling the Past through Virtual Reality (Project led by Prof. Victor Flores, Universidade Lusófona de Lisboa). https://cinemaeartes.ulusofona.pt/pt/noticias/3085-o-panorama-do-congo-desenrolar-o-passado-atraves-da-realidade-virtual.

Vanderlyn, John. 1818–1819. Panoramic View of the Palace and Gardens of Versailles. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/13052.