Abstract

This paper compares the different introductions of Miss Havisham’s character across prominent adaptations of Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations, including films by David Lean (1946), Alfonso Cuarón (1998), and Mike Newell (2012), as well as multiple recent television miniseries. While the adaptations differ, sometimes greatly, an integral moment in each story is the protagonist Pip’s introduction to Miss Havisham and, by extension, to her ward Estella. This scene, depicting Pip’s entrance into a new setting, often showcases each adaptation’s main themes and concepts. By focusing on this introductory scene, we compare framing, lighting, costuming, dialogue, and blocking to explore how various filmmakers have reinterpreted Miss Havisham’s character and what those choices reveal about shifting perspectives. By analyzing these various film and television adaptations from different eras and directors, this study examines how each portrayal reflects the cinematic trends and socio-cultural concerns of its time.

Keywords: Charles Dickens, Great Expectations, Adaptation, Literature, Staging.

Introduction

Charles Dickens (1812-1870) is perhaps one of the most celebrated English novelists of all time. His novels and short stories have long been part of school curricula and widely acclaimed by critics and scholars alike. His work has even led to the coining of the word “Dickensian”, now used to describe works reminiscent of his style and the grimness of the world his characters inhabit. Over the course of his life, Dickens published fifteen novels. Great Expectations, one of his final works, was originally published as a weekly serial in All the Year Round, a periodical he owned and edited, from December 1st, 1860, to August 3rd, 1861. The novel was initially intended as a means to remedy a drop in sales but due to its widespread appeal it quickly delighted readers and critics alike, making it an immediate success not only in England but also in the United States. The novel has since remained one of Dickens’ most beloved works (Hammond 2018, 275).

Set in early nineteenth-century England, Great Expectations follows Philip Pirrip, or “Pip”, a young orphan boy being raised by his sister and her blacksmith husband, Joe. The novel begins with Pip’s unsettling childhood encounter with, and subsequent helping of, an escaped convict, Magwitch. Soon after, Pip is summoned to the home of the wealthy and reclusive Miss Havisham to “play” with her ward, Estella, Pip’s future romantic interest. This formative visit sets the stage for Pip’s aspirations and marks his first foray into the unknown world that belongs to the upper class of society. Later, when an anonymous benefactor bestows Pip with the means of becoming a “gentleman”, he wrongly believes this to be Miss Havisham’s doing when, in fact, it is Magwitch. The novel then traces the transformation Pip undergoes to fulfill these new “great expectations” that have been placed upon him and follows how his relationships, such as with his brother-in-law or with Estella, are changed by his new status and understanding of the world.

The story is what is called a “Bildungsroman” as it traces Pip’s psychological and moral growth “in the passage from childhood through varied experiences – and often through a spiritual crisis – into maturity, which usually involves recognition of one’s identity and role in the world’” (Abrams 1999, 193). While Pip and his transformation are the central focus of the book, Miss Havisham’s presence, as Pip’s potential (but not actual) benefactor and Estella’s main influence, situates her as an essential narrative catalyst and causes her to encapsulate many of the novel’s main themes. With her decaying bridal dress, stopped clocks, and the all-consuming grief of her failed wedding, Miss Havisham has become a cultural archetype of lost time, unresolved trauma, and mad, scorned women.

Dickens’ work has lent itself to countless adaptations across various media over the years, making him one of the most frequently adapted authors in literary history. While A Christmas Carol remains the most frequently retold of his stories, Great Expectations has also seen its fair share of adaptations, each emphasizing different aspects of the characters.

The aim of this paper is not to provide a comprehensive comparison of all Great Expectations adaptations but rather to focus on one recurring key moment within the narrative: the introduction of Miss Havisham. This moment, beginning with Pip’s arrival at Satis House and ending with his “playing” with Estella, while relatively brief in the novel, serves as a critical moment in the story; it not only introduces two of the novel’s most important female characters: the eccentric Miss Havisham and Estella, but it also marks Pip’s entry into the world of the wealthy and sets in motion his fascination with the upper class. Therefore, by focusing on this one scene - and its choices of mise-en-scene, costume, performance, and tone - we can see how the novel’s two main female characters are depicted and which of their characteristics are highlighted in each film, as well as how each depiction chooses to present this image of luxury and degradation.

While many adaptations of Great Expectations exist, some are lost and some are inaccessible. This paper will focus on a close comparative analysis of the more renowned and widely circulated adaptations: David Lean’s highly acclaimed 1946 version, Alfonso Cuarón’s 1998 modernization, and Mike Newell’s 2012 return to the Dickensian style, alongside two of the more recent television miniseries from 2011 and 2023. Starting from a BBC adaptation in 1959 and all the way to the most recent one in 2023, there have been various retellings of Great Expectations in the form of a mini-series. With their extended runtime, these mini-series adaptations often reintroduce characters and backstories that the movies have skipped over. In this context, we will focus primarily on the two most recent adaptations and on the changes and additions, if any, they have made to the introduction of Miss Havisham. Overall, some adaptations show Miss Havisham as a bride, while others focus on her craziness, some show her as ethereal, and some as resembling a ghost. Similarly, some of the films discussed will immediately present Estella as a romantic interest, while others emphasize her arrogance or coldness. The directions taken can provide us with an insight into how a figure of an old, rich “spinster” is seen in comparison with a younger, more desired character and what these choices and reimaginings can reveal about the production’s time period and the director’s evolving visual styles and ideologies.

Literature Review

Adaptation Theory

Adaptation studies provide a framework to understand why various adaptations exist, what the incentive is for certain stories to be told and retold, and how each re-interpretation reflects political, cultural, and aesthetic concerns of the time. Audiences, likewise, engage with works depending upon the social and cultural context of the time and place they are set and viewed. According to Linda Hutcheon in her book A Theory of Adaptation, this engagement depends on matters “material, public, and economic as much as they are cultural, personal, and aesthetic” (Hutcheon and O’Flynn 2013, 28).

There are many ways of looking at adaptations and understanding retellings. Adaptation is not merely translating from one medium to another; if that were the case, one version would suffice to get the story across. With each adaptation, “stories evolve and mutate to fit new times and different places” (Hutcheon and O’Flynn 2013, 176). Changing the story’s context, drastically impacts how adaptations are read, both narratively and conceptually.

This study is not concerned with the adaptation’s “fidelity” to Dickens’ novel. Rather, we focus on what each adaptation brings to the foreground. As Brian McFarlane notes in Novel to Film, fidelity criticism “depends on a notion of the text as having and rendering [...] a single, correct ‘meaning’” (McFarlane 1996, 8), which is a subjective approach. Fidelity criticism also ignores those who are unfamiliar with the source material and underscores other aspects of the film’s intertextuality, such as current industry trends and the sociopolitical climate of the time (McFarlane 1996, 21).

Finally, as Robert Stam argues, we must ask whether we can even achieve or strive for fidelity as, changing the format, already alters the material (Stam 2000, 55). Therefore, this paper will favor comparisons between adaptations over comparisons to the novel and will avoid passing judgement on their “fidelity” or “success” in meeting audience’s expectations; instead, we ask why each of these adaptations exist and what cultural and aesthetic visions they realize.

Charles Dickens on Screen

Charles Dickens is among the most highly adapted authors in history. Sergei Eisentein’s writings on the connection between Dickens and motion pictures showed the writer’s influence has made its way into cinema through the director D.W. Griffith, whose montage technique was derived from the parallel action present in Dickens’ texts (Eisenstein 1977, 205). Apart from providing the inception for a technique that would propel cinema forward, Dickens’ writings are described by Eisenstein as having “extraordinary plasticity“ and “optical quality”, rendering characters similar to what would be seen on screen (Eisenstein 1977, 208). As such, Dickens’ grim narratives, vivid characters, and serialized structures have made his novels particularly suitable for film and television.

Great Expectations has seen a wide range of screen versions. As Brian McFarlane outlines, these include: an American silent film (1917, now lost), a Danish silent film (1922), the first American “talkie” (1934), David Lean’s adaptation (1946), a made for TV UK version (1975), an Australian animation (1980), and a modern retelling (1998). In addition, he also notes multiple mini-series from 1959, 1967, 1981, 1989, and 1999 as well as multiple radio, stage, and graphic novel adaptations, and spin-offs (McFarlane 2008, VI). Since McFarlane’s book was published, an additional movie (2012) and two additional TV shows (2011, 2023) have been released.

As mentioned, Great Expectations was published in thirty-six weekly installments, a structure that mirrors that of a serialized show. Jeffrey Sconce mentions that the narrative form in television is greatly inspired by Dickens and his (and other nineteenth-century novels’) focus on episodic storytelling (Sconce 2003, 183) while McFarlane goes as far as to say that “the mini-series was invented for the visual realisation of Dickens” as Dickens was known for the concept of keeping audiences hooked via weekly installments (McFarlane 2008, 63).

As Mary Hammond explains in The Oxford Handbook of Charles Dickens, Dickens wrote with “what we now call multiplatform publishing” (Hammond 2018, 275) in mind. His desire to increase profits led him to structure the novel and shape the text to make it work on different levels simultaneously; meaning that not only did every three-chapters need a small cliffhanger but also that it needed comic potential for caricatures in the American version while having the “verbal colour and complexity to enable it to work without them [...] for the British” (Hammond 2018, 276). Dickens even anticipated the need to appeal to audiences abroad as well as the possibility that the book would be read aloud to groups of listeners and so he adapted the novel to a reading version that was never performed (Hammond 2018, 276).

Rachel Malik describes the novel as having a capsular mode of narration or “capsularity”, meaning there are multiple plots worked in such a way to create “relatively autonomous stories”. This characteristic allows for faster “multiform publishing” such as abridgements, anthologizations, and adaptations to other forms of public performances, which aligns with Dickens’ publishing intentions (Malik 2012, 485).

This flexibility has made Great Expectations highly adaptable in a way that “various segments of the novel have offered themselves for dramatization and rewriting ranging from the reverential to the parodic” (Hammond 2018, 277). While the book highlights Pip’s relationships with male characters such as Joe and Magwitch, film adaptations often aim to appeal to female audiences and, as such, focus on the romantic subplot between Pip and Estella. In doing so, they bring Estella, and by extension Miss Havisham as an antagonistic force against the romance, to the foreground (Hammond 2018, 281).

Miss Havisham

In a structural analysis of narratives, Roland Barthes distinguishes between two categories of narrative units: Cardinal Functions, on which the narrative hinges and which “opens (or maintains or closes) an alternative directly affecting the continuation of the story” and which “either initiates or resolves an uncertainty” (Barthes and Duisit 1975, 247), and Catalyses, which complement and mainly “fill in” the space between those functions. If we are to split Great Expectations into different Cardinal Functions, as McFarlane has done, we arrive at 54 key moments in the story (McFarlane 2008, 9-11). One of the most pivotal early moments, kept intact in almost all adaptations, is Pip’s first meeting with Miss Havisham. This scene operates as a narrative hinge as it initiates Pip’s entry into a different social setting and plants the emotional seeds of his ambitions and desires.

Therefore, although Miss Havisham is not the protagonist, she has become one of Dickens’ most iconic characters. Her imagery is unmistakable: a woman in a bridal dress who is frozen in time and surrounded by dust, cobwebs, and decay.

In the book, she is first referred to in preparation for Pip’s visit and then further described in haunting detail when Pip finally sees her:

I saw that the dress had been put upon the rounded figure of a young woman, and that the figure, upon which it now hung loose had shrunk to skin and bone. Once, I had been taken to see some ghastly waxwork at the fair, representing I know not what imposible personage lying in state. Once, I had been taken to one of our old marsh churches to see a skeleton in the ashes of a rich dress, that had been dug out of a vault under the church pavement. Now waxwork and skeleton seemed to have dark eyes that moved and looked at me. (Dickens 2014, 52)

In a 2014 survey of 2,000 British adults, Miss Havisham was selected as “the most haunting female character from dramatised literature” (Mitchell 2014). She embodies arrested development and is often seen as a gothic figure despite Great Expectations not being classified as gothic. Elizabeth MacAndrew describes gothic fiction as “a literature of nightmare” featuring “dream landscapes and figures of the subconscious imagination” in which the story often revolves around “concepts of the place of evil in the human mind” (MacAndrew 1979, 3). By contrast, Great Expectations, falls under the category of sentimental fiction which “educates the reader’s emotions” (MacAndrew 1979, 24) and aims to make them “weep with and for the afflicted characters” while gothic stories tend to “inspire pity and terror” (MacAndrew 1979, 26). Miss Havisham’s story of the woman who hasn’t seen the sun since before Pip was born reads less like a realist character and more as a gothic apparition within the larger context of Pip’s sentimental story. Therefore, she stands out in the novel as not belonging to the world the story is set in which further sets her apart and adds to her image of disconnect.

Camilla Nelson’s study on female rage defines Miss Havisham as a spectral spinster “that haunts the western imagination [...], a repository for masculine fears and fantasies about women, age, sexuality, and power” (Nelson 2019, 224). Her fury is framed as the “product of a nineteenth-century capitalist society that constructed women as irrational and unstable creatures, and kept them legally, economically, and socially powerless” (Nelson 2019, 225). Hammond echoes this view by stating Miss Havisham is seen as “monstrous” because she is “a rich, powerful, and influential woman too old to be a sex object” while “bearing the deep scars of a previous male rejection” (Hammond 2018, 280).

Miss Havisham’s image as the “scorned bride” has evolved over time, reflecting the cultural shifts in such depictions. In a study on her costuming, Regis and Wynne view her wedding dress as a distortion of “all of the cultural meanings surrounding the bride, especially those linked to notions of hope, fertility, and renewal” (Regis and Wynne 2012, 37). The failed bride trope is used to “signal the failure of femininity and the uncanniness of the ageing woman’s body in an era when health, beauty and youth are presented to cinema audiences as the desirable norm” (Regis and Wynne 2012, 39)

While Dickens’/Pip’s description of Miss Havisham heavily relies on imagery of the macabre and decaying, as a figure that had “shrunk to skin and bone” or the mixture of “waxwork and skeleton” (Dickens 2014, 52), the character is not as old as traditionally depicted and is estimated to be in her forties in the novel. However, in most adaptations, she is usually played by older actresses in their sixties and seventies, and is one of the main iconic roles available to this age range (Nelson 2019, 4)

This paper now turns to how different adaptations have chosen to interpret Miss Havisham’s introduction. We focus on 3 main film adaptations along with the two recent mini-series (2011 and 2023). The focus will be on what each adaptation chooses to highlight and we will look at the mise-en-scene, costuming, dialogue, tone, and framing of the scene in question. By situating each film within its production context, from post-war Britain to late-90s America, we will look at the bigger picture to fully understand the shifts Miss Havisham’s image has gone through over time.

David Lean’s Great Expectations (1946) and Miss Havisham: The Spider

David Lean’s 1946 adaptation remains one of the most critically acclaimed and cinematically influential versions of the story. At the time, Lean had already established himself as a director, and his reputation would only grow with later films, including another Dickens adaptation, Oliver Twist (1948). The British Film Institute’s 1999 list of the top 100 British films includes seven by Lean, making him the most represented director, with his Great Expectations ranked 5th. This adaptation was directly inspired by a theatrical staging of the novel by Alec Guiness. (Hammond 2018, 279) and even cast the same actress, Martita Hunt, in the role of Miss Havisham with her performance setting the standard for future portrayals.

The film follows the core arc of Pip’s journey from humble origins to “great expectations” while trimming subplots and characters to fit within its 118-minute runtime. A significant change is the addition of a happy ending. The film’s release in post-war Britain is especially significant. As McFarlane notes, British cinema during this period was focusing on themes of national identity and the attempt at creating a national voice through a return to classic literature as a source of pride (McFarlane 2008, 129).

In this version, as in the novel, the scene begins with Pip observing Estella at the window. She then meets him at the gates and plays the role of an arrogant guide, leading Pip through the darkness of the house and preparing him for his meeting with Miss Havisham by belittling him. “Pip follows Estella in nearly every shot; [...] She is the artificial light of the cloistered, nightmare environment created by Miss Havisham” (Barreca 2003, 42). The light belongs to Stella and when she goes away, so does the light (Barreca 2003, 42). This aspect symbolizes her as both the guide and the bait.

Lean establishes Satis House as a place suspended in time, using the imagery of the book. A large external clock and a hallway clock, both stopped, are remarked on by Pip. A third stopped clock is later seen behind Miss Havisham, reinforcing the theme. The mise-en-scène is dominated by heavy cobwebs in the foreground of both the staircase and inside the room, evoking the image of neglect in a house that, otherwise, appears mostly empty.

As Pip opens the door, he unveils Miss Havisham and the room in a wide shot. She sits stiffly and appears to be absorbed by the furniture, gathering dust and cobwebs so it takes a moment for us to register her presence. Her veil blends seamlessly with the cobwebs, adding to the concept of her being part of the room. The space is both her domain and a manifestation of her emotional state. The room itself, though devoid of sunlight, is brighter than the dark corridor Pip waited in. Sitting in the middle of cobwebs, Miss Havisham (image 1) brings to mind the image of a spider setting a trap for Pip and Estella. She is “a predatory spider in a web of dilapidation, a malign web in which both Estella and Pip are caught” (McFarlane 2008, 140).

Since the image of a bride is mainly associated with youth, this vision of an older lady in an old bridal dress is as off putting to Pip as the cobwebs are. The dress itself is an “Empire-line gown” which dates her and places her outside both the audience’s contemporary fashions and the film’s own inner historical setting; thus making her “a relic of the past twice over” (Regis and Wynne 2012, 45).

Miss Havisham remains seated, beckoning Pip closer. He doesn’t seem afraid, but trepidation is felt in his reluctance to get near her and the camera, moving in stages with him, emphasizes this. Miss Havisham’s one dramatic movement is when she gives a theatrical pronouncement of the iconic “broken heart” line, adding an eerie gravitas to the moment.

Lean also makes symbolic use of props, particularly drawing our attention, via close-up, to a cobweb-covered prayer book (image 2), implying Miss Havisham’s loss of faith. In contrast, the other items on the vanity table (the mirror and comb) have no cobwebs and suggest a continued attention to her self-image.

When Estella returns, the dynamic between the three solidifies and Miss Havisham’s image as a spider playing with her prey is augmented as she beckons Estella to her with the promise of jewels. Estella smiles warmly at Miss Havisham and only resumes her tone of haughtiness when addressing Pip. Prompted by Miss Havisham, Pip describes Estella as “proud”, “pretty”, and “insulting”, just like in the book. While this first encounter may hint at romantic tension, the main focus is on Pip’s discomfort and timidity.

From a feminist lens, this depiction is a reflection of the somewhat conservative values and the dynamics of the time. Post-war Britain saw women ushered back into more domestic roles after being brought into the workforce during wartime. As such, Miss Havisham, a wealthy unmarried woman is portrayed as a cautionary tale of what occurs when a woman is left abandoned. This version of Miss Havisham is unlike any other in that it is “replete with both conventional and subversive images of women” (Barreca 2003, 39). Ultimately, Lean’s Havisham becomes both a symbol of lost femininity and a haunting reminder of the dangers of female autonomy left unchecked.

Alfonso Cuarón’s Great Expectations (1998) and Miss Dinsmoor: The Hippie

Alfonso Cuarón’s 1998 adaptation is perhaps the version that differs the most from the source material. Known today for films such as Gravity (2013) and Roma (2018), Cuarón was still in the early stages of his international career and, for him, this project marked a challenge in the attempt to place a classic British novel within contemporary American culture. Although Cuarón loved the novel and dreamed of exploring its class themes, he felt studio preferences prevented him from fully realizing that vision (Katz 2003, 97).

Judged through a fidelity lens, this is the least “loyal” adaptation as the setting, time, and even character names have changed. Pip becomes “Finn”, Miss Havisham becomes “Miss Dinsmoor”, and the story takes place now in Florida and Manhattan. Finn aspires to be an artist rather than a gentleman, “replacing the arbitrary wealth of the nineteenth century with the twentieth-century equivalent: celebrity success” (Katz 2003, 97). Estella is a socialite, and Miss Dinsmoor’s eccentricity reads as more unhinged than tragic. Of McFarlane’s 54 cardinal functions, this adaptation retains “no more than 19” (McFarlane 2008, 115). Yet, despite these changes, the core of the story remains, allowing it to qualify as an adaptation.

The backdrop of 1990s America influences all the decisions here. In this setting, being an unmarried woman no longer carries the stigma it once did. The atmosphere of the film, therefore, embraces a more sexual tone and showcases “an attitude to sexual matters that Dickens’s characters could not have dreamed of” (McFarlane 2008, 121). Cuarón himself said that “if Dickens were writing today, he would have more sex in his own novels too.” As a result, the script focuses on the theme of unrequited love or “erotic obsession” since, according to Pamela Katz, Cuarón knew that he needed to include a “steamy romance, or the budget would go way down” (Katz 2003, 96-97).

In this vein, Estella is reimagined and introduced earlier, in a standalone scene focused on romantic intrigue so that when Pip visits to “play”, it is their second meeting. In that second meeting, she plays a know-it-all tour guide and retains her usual snobbery while showing off the house’s faded luxury. Though everything is beautiful, it seems mausoleum-like and neglected. There is gold and ornaments everywhere but nothing is “clean”.

Miss Dinsmoor, played by Anne Bancroft, diverges significantly from earlier portrayals. Gone are the cobwebs, clocks, and bridal imagery. Instead, she is shown as an aging, eccentric with an overly white made-up face who is introduced dancing alone with her back to us, framed through a birdcage. Instead of cobwebs holding her in place, the cage becomes a metaphor for her entrapment with the bird symbolizing either Estella or Pip, her playthings. She appears mentally adrift as she only registers Pip’s presence mid-dance. This detachment is later hinted at through her alcohol consumption. She aligns more with modern-day stereotypes of a “crazy cat lady” than a jilted bride.

Instead of stopped clocks, her stagnation is shown through the constant repetition of the old song Bésame Mucho (meaning Kiss Me a Lot). Adding to the image of being stuck in time is her outdated fashion of the 1960s. She does not wear a bridal gown as, in this new setting, weddings no longer carry the same weight as the sole rite of passage into womanhood.

Cuarón and Bancroft don’t reference Lean’s gothic portrayal, but another reimagining of Miss Havisham: Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950). While not a direct adaptation, that films bears striking thematic parallels and, is “a cynical homage to the mythic power [...] of “that Dickens novel,” in which a boy first came to “play” for an aging woman’s pleasure, in a decrepit mansion” (Marsh 2001, 215). In this vein, Norma Desmond and Dinsmoor (even similar in name), both share the habit of cigarettes and cigarette-holders, “mirrored costumes” and “long, glamorous headscarves”. Both are also depictions of an aged woman who seems to be clinging to her youth through an emphasis on multiple mirrors, beauty products, and heavy make-up (Regis and Wynne 2012, 49).

Dinsmoor’s room, though messy and said to “smells like cat piss” (reinforcing the “crazy cat lady” idea), is alive and shows clear wealth (image 3). Unlike Miss Havisham, who is frozen in one specific day (her wedding), Dinsmoor is stuck in a bygone era. Further removing her from the wedding motif is the fact that the wedding items are all outside the house and, thus, physically distanced from her.

The tone of this scene is more comical overall. A telling moment is how Miss Havisham’s line about her broken heart is reinterpreted. Rather than touching her own chest and asking what she’s touching, as she normally does, Dinsmoor takes Pip’s hand and places it on her chest, prompting the irreverent response of “your boob” instead of “your heart” and undercutting the emotional weight of the moment (image 4).

Visually lush and stylized, Cuarón’s version favors camp and spectacle over gothic tragedy and this Miss Dinsmoor is not necessarily traumatized but rather a relic of the past, haunted more by her irrelevance and age than by her heartbreak.

Mike Newell’s Great Expectations (2012) and Miss Havisham: The Haunted Bride

Released during the bicentenary of Charles Dickens’ birth, Mike Newell’s 2012 adaptation was part of a wave of renewed interest in Dickens by the BBC and British media, including a Great Expectations TV show that premiered at the same time (December 2011) which will be discussed in the next section. In this context, Newell’s return to the heart of the text and his attempt at “fidelity” can be seen as a celebration of the Dickensian legacy as well as an attempt to (re-)introduce modern audiences to the novel. Rather than being entirely realistic, his adaptation finds a balance in the neo-Gothic aesthetic of the original Victorian era.

Helena Bonham Carter is this version’s Miss Havisham, building on her established persona as a gothic eccentric as depicted through her roles in the Harry Potter franchise (2001-2011), Corpse Bride (2005), and Sweeney Todd (2007). Her casting allows us to read this Miss Havisham within the archetype of the “mad woman” that she normally portrays.

As in Lean’s version, Estella greets Pip at the door (this time inside, not at the gate) and guides him up a dark staircase holding a candle. Though this time, the cobwebs are less pronounced and there seems to be no sense of luxury or grandeur in this dark empty house.

Miss Havisham is introduced gradually through tight POV close-ups of objects as observed by Pip: an unlit candle chandelier, boarded windows with sun rays seeping through, a stopped clock, and torn book pages scattered on the ground. Finally, Miss Havisham’s reflection appears suddenly in a close-up on the mirror and is accompanied with a dramatic sound cue in a visual jump scare meant to echo Pip’s fear. She sits alone in a room that looks to have lost the impressiveness it once had.

Noticeably absent from the dialogue is the line about her broken heart. This Miss Havisham is less sorrowful and more unhinged than other depictions. She has a very pale face that is accentuated by white-ish contact lenses. Her main prop is a monocle she repeatedly uses when looking at Pip, a possible visualization of her limited and distorted worldview. Fully adorned in bridal wear, this version also leans in heavily to the wedding imagery. At one point, when beckoning Pip closer to her, she puts her bridal veil on, drawing further attention to this element.

Despite her claim to have “not seen the sun” since before Pip was born, the film’s attempt at realism and realistic lighting seems to contradict that by having visible rays of sunlight coming in through the cracks in the boarded windows (image 5) to the point that Pip, and later Estella, are illuminated by the sunlight with the proper exposure, signifying sufficient light has made its way inside. It is unclear whether this is meant to draw attention to Miss Havisham’s loss of touch with reality or if it is a case of the stylistic inconsistency.

When Estella re-enters the room, she lays her head on Miss Havisham’s lap as a sign of devotion but also potential temptation for Pip. In one move, Miss Havisham dangles a necklace in front of Estella (image 6) while also metaphorically dangling Estella in front of Pip.

However, even the necklace lacks the apparent opulence of earlier depictions, reflecting a shift in portrayals of wealth and class. We could read this choice as a hint that, while she may not appear wealthy to our modern standards, even this level of wealth was, at the time, unattainable for someone like Pip; thus, adding to the tragedy of his situation.

A standout moment in this adaptation occurs when Miss Havisham brings Pip into her veil when asking her usual question of what he thinks of Estella (image 7). We then see Estella through Pip’s eyes, literally veiled as sinister music plays. This is the first of the movie adaptations so far to showcase this level of proximity between Miss Havisham and Pip and it seems to hint at a layer of unsettling sensuality. As seen in this moment, she is physically and figuratively entrapping Pip.

Great Expectations (2011) and Miss Havisham: The Ethereal Ghost

The 2011 BBC adaptation, written by Sarah Phelps, is a three-part miniseries, each episode an hour long, with Gillian Anderson cast as Miss Havisham. At 43, Anderson was the youngest actress to take on this role. In a Telegraph review of the first episode, she is called a “pale yet still beautiful wraith [...], speaking in insidious singsong instead of the usual dotty dowager tones”, a version of the character “who has never really grown up” (Billson 2011). Anderson herself has noted that the character’s perceived age may be a misconception “because of course it’s written from Pip’s perspective, and when I was 12, anybody above the age of 25 looked ancient”. She also draws attention to the presumed fact that Miss Havisham’s heartache, which occurs 25 years prior to Pip’s meeting her, happened when she was 18 or 20, thus placing her in her mid-forties. She suggests that a younger Miss Havisham could be “more provocative when older Pip shows up” (Gordon 2011). Series writer, Sarah Phelps has echoed this sentiment, stating she “‘didn’t want her to be a gargoyle or a grotesque or someone who is a bit nuts for the sake of it” and chose to imply that her broken heart happened in the not so distant future and that “she was still in the white heat of rejection” in order to make the audience relate to her and empathize with her situation (Williams 2011).

We meet Miss Havisham around minute 19, a third of the way into episode one. Right from the start of the scene, a notable change is the removal of Estella from the initial tour of the house. Rather than greeting Pip and setting the stage for Miss Havisham through her behavior, she is replaced by a maid who admits him. This shifts the focus entirely to Miss Havisham as she is the first to be introduced while also reserving Estella’s entrance for a more dramatic, romantic effect.

Estella’s later introduction is dramatized by a slow dolly-in and heightened emotional music. She’s shown in a more favorable light as she’s introduced after this softer version of Miss Havisham. She’s also called Miss Havisham’s “adopted daughter” (not “ward”) and she likewise calls her “mother”, humanizing both characters. This version foreground’s Pip’s immediate emotional reaction to Estella and sets up the love subplot early.

Before meeting Miss Havisham, we see the usual stopped clock, preserving Dickens’ motif of a place lost in time, at the bottom of a staircase where Pip waits for Miss Havisham. A major change is that she comes to him, descending gracefully, lit from behind like an apparition (image 8). Her white hair truly sells the image of her as a ghost and further enhances her disconnect from the living world. She even speaks in an otherworldly soft tone, and already knows Pip’s name. Miss Havisham’s appearance is so awe-inspiring that Pip immediately removes his hat when he sees her as a sign of reverence rather than fear

While her white dress may be a bridal outfit, it lacks traditional markers such as the veil or jewellery. More than appearing bridal, she seems ghostly as the emphasis is on her paleness and fragility (image 9). She is also barefoot, a fact Pip remarks on, asking if she’s cold, to which she replies, “all of me is cold” emphasizing her physical delicacy. Her lips and the back of her hand also speak of an illness and frailty.

Miss Havisham then leads Pip to another room, offering a second visual introduction as he now observes her in this new lived-in setting (image 10). Here too, like in Cuarón’s version, there are no visible wedding remnants; instead, the room feels like a cluttered museum that she invites Pip to explore freely.

Anderson’s Miss Havisham is more talkative, speaking openly about her thoughts on beauty and the lives of men. Another notable addition is her story about her brother who, in this version, travelled the world seeking beautiful things (specifically butterflies) only to kill them; offering us an allegory for destruction through possession and evoking a counterpoint to Miss Havisham’s own entrapment in the pinned and framed butterflies. This backstory replaces the usual “broken heart” speech and alludes to a shift in focus toward familial trauma, placing the damage caused by her brother as the cause of her suffering rather than her romantic abandonment. In the book, the cause of her broken heart is tied to money and deception but here, the emphasis is on this deeper psychological pain implied to be a result of her being wronged by her family.

Anderson’s relative youth and the fact that she’s mobile and moving around a bright house subverts the audience’s expectations in some ways. It can disappoint audiences that are accustomed to the image of an older lady that lives protected from sunlight and it presents us with a somewhat sadder understanding of this character. Her mobility removes any kind of visibly physical limitation to her leaving the house and attributes her solitude to her incapability to emotionally deal with her failure rather than a physical obstacle due to her age. The image we’re presented with solidifies the understanding and entraps the imagination of a woman who is depressed rather than crazy. She can go out but decides not to.

Overall, considering her increased lines of dialogue, her movement within the space, and this slight shift from a broken heart to a deeper sorrow, this Miss Havisham feels like a more modern take in line with the types of complex female characters audiences were accustomed to in 2011 and more grounded in her emotional fragility rather than melodrama.

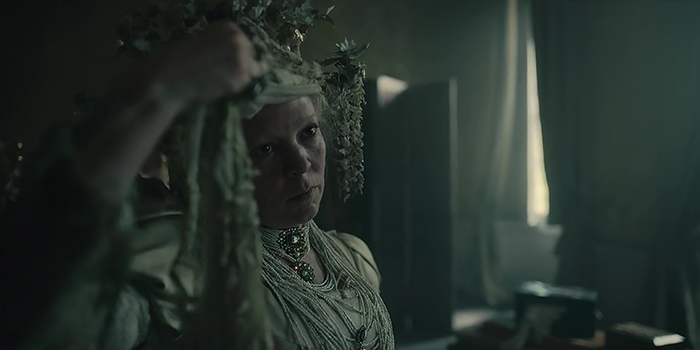

Great Expectations (2023) and Miss Havisham, the Sinister Tyrant

The most recent adaptation, a co-production between the BBC and FX, aired in 2023 and was written by Peaky Blinders creator Steven Knight. It spans six episodes with each episode roughly being an hour long. Miss Havisham’s first appearance marks the end of the first episode and heightens her impact. Here, Pip arrives at the house at minute 47 of 56, and his meeting with Miss Havisham lasts until the ending cliffhanger, to be resumed in the second episode. Played by Olivia Colman, this Miss Havisham is cold, commanding, and more sinister. A review on The Guardian referred to Colman’s Miss Havisham as having “a creepier, more predatory, vibe than we are used to seeing” and posed the question of whether we are supposed to “read her as a proto-groomer” in this “deliberate reflection of our times”, potentially influenced by the prevalence of predators existing in our society (Mangan 2023).

In this scene, as is common, Estella greets Pip at the gate and takes him on the tour of Satis House but there are two main elements added to Pip’s entrance that appear in no other adaptation that we’ve seen so far. First, it relies more on the depiction of coldness by using a dark blue atmosphere in the exterior alongside the presence of light snow (image 11). The second addition is Stella’s treatment of Pip like a dog who is commanded around and whistled to. Though these elements can be traced to the source material where light snow is described in Pip’s second visit to the house (Dickens 2014, 72) as well as the dog-like treatment he receives from Stella (Dickens 2014, 56), these characteristics are highlighted here to support the somber depictions of the inhabitants of Satis House.

Another uncommon approach comes right after when we have a momentary break from Pip’s first-person narrator role as the camera offers Miss Havisham’s perspective observing the two of them through the window (image 12). This shows Miss Havisham as an all-knowing character but also adds to the tension since it hints at control and surveillance.

The interior of the house, while neglected and dusty, is grand and luxurious in its architecture. Shown first through a wide crane shot, when Pip enters, we sweep with the camera and see a full view of the space which emphasizes how ample it is. Estella and Pip walk slowly up the stairs and through the corridor with Estella mentioning that ghosts are afraid to come to this house. This mention of ghosts is also unique to this adaptation and the music used adds to the feeling of horror, suggesting a dark layer underneath it all since even ghosts fear the skeletons in the closet. When we approach the door to Miss Havisham’s room, the camera floats eerily as if one of the aforementioned ghosts.

Miss Havisham herself is shown in a wide-shot, from behind as she stands perfectly still, almost statuesque (image 13). Before fully seeing her, we first see a reflection of her silhouette on the stopped clock, further emphasizing the image of her being stuck in time in the most literal depiction of the concept (image 14).

Finally, she turns and moves her face to us; however, as she’s wearing a thick veil, no features are clear until Pip, followed closely by the camera, walks towards her and she unveils, urging him to “look on what remains of me”. Visually, this Miss Havisham is more adorned in bridal jewels with excessive ornamentations of lace, veils, and pearls (image 15). As a result, she may be the most visually wealthy depiction of Miss Havisham thus far. She is harsher, more expressive, and less fragile than Anderson’s depiction and overall seems much more sinister than all previous versions, often intense in her vocal delivery.

Here too, like the Newell version, there is sunlight streaming in through the window; however, the line about Miss Havisham having not seen the sun has been cut. Instead, Estella makes a reference to “eternal winter” which, combined with the snow outside, adds to the coldness of the moment and of the setting in which the adaptation takes place.

Another change is in Miss Havisham being the one who makes the comment about Estella being “pretty”, something often offered by Pip. She is, so to speak, putting words into his mouth and luring him into following the path she envisioned for them both. The episode ends right before Estella and Pip’s usual “playing”; however, not before Miss Havisham makes a pronouncement about the two of them, letting the audience understand that the “play” Pip was brought to do does not refer to any sort of game but to toying with their lives. This is then confirmed in episode 2 which shows not the usual card game but rather a manipulative game of hide and seek which clearly showcases Miss Havisham’s intentions and depicts her as a puppeteer planning on throwing them towards each other while also impeding their relationship.

As pointed out by a critic for the The New Yorker, Knights’ adaptation updates certain aspects of the story’s backdrop and decides to bring to the fore “allusions to the sins of the British Empire” such as the slave trade and opium. While the source of Miss Havisham’s riches is not clearly defined in the novel, we will come to find later in the show that these are the very lines of business that sponsored her wealth in this version. These changes come to update the adaptation to modern expectations and to portray aspects of the Victorian Age that are not the focus of Dickens’ novel but Knight chose to emphasize here. According to the same article, this would serve to bring a reminder to viewers about “where much of England’s wealth in this period came from, and at whose expense” (Kang 2023).

This introduction relies heavily on horror-like elements such as low-key cinematography and eerie sound design and, in doing so, reflects the overall desire to update the classic character with a more modern approach to class-struggle. Knight presents us with a revision of the Victorian Era backdrop presented by Dickens and largely focuses on how unethical certain fortunes can be. This Miss Havisham comes to represent the corrupt rich and presents a more palpable understanding of how improbable it was to move up the social ladder at the time of the novel and nowadays. This crueler, more fear-inducing depiction of Miss Havisham is then a result of not just a broken heart but generational cruelty.

Conclusion

Adaptations of Great Expectations go beyond direct recreations of the novel and into the realm of popular culture where the relationship between Pip and Miss Havisham has taken on a life of its own. Over the years, Miss Havisham has become a widely recognized symbol, representing the dangers of an unfulfilled romantic fantasy and the fear of female emotional excess.

There is, for instance, an entire South Park episode titled “Pip” (2000) which was a parodic retelling of Great Expectations. Similarly, shows like The Simpsons have also referenced Miss Havisham, both visually parodying her crumbling bridal gown and referring to her eternal “spinsterhood” in dialogue. In general, it seems Miss Havisham has come to be seen in the public eye as a classic example of failed femininity, and is often the butt of jokes about loneliness and the mad woman archetype.

Across the five adaptations analyzed here, we can trace shifting understandings of Miss Havisham in relation to depictions of class, gender, and trauma through the changes in visual aesthetics and central themes. Lean’s version portrays her as a tragic, gothic, spider and a relic of post-war cautionary women. Cuarón’s Miss Dinsmoor is a campier, Sunset Boulevard-inspired eccentric who signals American anxieties of age and madness. Newell’s depiction leans heavily into the neo-gothic tragedy of a mad woman while, at the same time, the 2011 version presents a more youthful yet fragile woman locked in her intimate grief. The 2023 version, meanwhile, provides us with the most overtly theatrical and sinister of the Miss Havisham’s we have seen, a cold and terrifying result of generational evil. These differences demonstrate how each era’s cultural sensibilities and production values shape not only the character’s visual representation but also her symbolic role in society.

As one of Dickens’ most symbolically rich characters, Miss Havisham offers directors a chance to showcase their motifs, ideologies, and tones all within a single scene. Whether ethereal or grotesque, her first appearance is consistently staged as a critical moment in Pip’s narrative arc as it lingers in Pip’s memory and grants him entry into a different world while introducing him to two of the most important women in his life.

Dickens has undeniable staying power and his adaptations are not going anywhere. It is likely that future adaptations will continue to reimagine Pip’s story and reinterpret Miss Havisham’s eccentricities, loneliness, and bitterness in line with the concerns of the time.

This study mainly focused on three key film adaptations and two major television miniseries but there is still a world of other films, series, animations, inspirations, and parodies as well as many non-English language reinterpretations to look into. Further research into these global retellings, as well as a look at stage and transmedia versions could deepen our understanding of how this narrative continues to evolve across cultures and platforms.

Bibliography

Abrams, Meyer H. 1999. A glossary of literary terms. N.p.: Harcourt Brace College Publishers.

Barreca, Regina. 2003. “David Lean’s Great Expectations.” In Dickens on Screen, edited by John Glavin. N.p.: Cambridge University Press.

Barthes, Roland, and Lionel Duisit. 1975. “An Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative.” New Literary History 6, no. 2 (Winter): 237-272. https://doi.org/10.2307/468419.

Billson, Anne. 2011. “Great Expectations, BBC One, review.” The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/tvandradio/8975722/Great-Expectations-BBC-One-review.html.

Dickens, Charles. 2014. Great Expectations. N.p.: Bloomsbury USA.

Eisenstein, Sergei. 1977. Film form : essays in film theory. Translated by Jay Leyda. N.p.: Harcourt, Brace.

Gordon, Bryony. 2011. “Gillian Anderson: ‘When he was just 30, my brother was prepared to die.’” The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/tvandradio/8971145/Gillian-Anderson-When-he-was-just-30-my-brother-was-prepared-to-die.html.

Hammond, Mary. 2018. “Great Expectations.” In The Oxford Handbook of Charles Dickens, edited by Robert L. Patten, John O. Jordan, and Catherine Waters. N.p.: Oxford University Press.

Hutcheon, Linda, and Siobhan O’Flynn. 2013. A Theory of Adaptation. N.p.: Routledge.

Kang, Inkoo. 2023. “Victoriana Drenched in Red Bull, in FX’s “Great Expectations.”” The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/04/03/great-expectations-review-fx.

Katz, Pamela. 2003. “Directing Dickens: Alfonso Cuaron’s 1998 Great Expectations.” In Dickens on Screen, edited by John Glavin. N.p.: Cambridge University Press.

MacAndrew, Elizabeth. 1979. The Gothic tradition in fiction. N.p.: Columbia University Press.

Malik, Rachel. 2012. “Stories Many, Fast and Slow: Great Expectations and the Mid-Victorian Horizon of the Publishable.” ELH 79 (2): 477-500. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23256762.

Mangan, Lucy. 2023. “Great Expectations review – Olivia Colman is mesmerisingly sinister.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2023/mar/26/bbc-great-expectations-review-olivia-colman-is-mesmerisingly-sinister.

Marsh, Joss. 2001. “Dickens and film.” In The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens, edited by John O. Jordan. N.p.: Cambridge University Press.

McFarlane, Brian. 1996. Novel to Film: An Introduction to the Theory of Adaptation. N.p.: Clarendon Press.

McFarlane, Brian. 2008. Screen Adaptations: Great Expectations: A Close Study of the Relationship Between Text and Film. Edited by Imelda Whelehan. N.p.: A&C Black.

Mitchell, Laura. 2014. “Heathcliff, Miss Havisham, Dracula: Most haunting characters in litera.” Daily Express. https://www.express.co.uk/entertainment/books/477078/Haunting-book-characters.

Nelson, Camilla. 2019. “Miss Havisham’s Rage: Imagining the ‘Angry Woman’ in Adaptations of Dickens’ Famous Character.” Adaptation 13, no. 2 (November): 224-239. https://doi.org/10.1093/adaptation/apz027.

Regis, Amber K., and Deborah Wynne. 2012. “Miss Havisham’s Dress: Materialising Dickens in Film Adaptations of Great Expectations.” Neo-Victorian Studies 5 (2): 35-58.

Sconce, Jeffrey. 2003. “Dickens, Selznick, and Southpark.” In Dickens on Screen, edited by John Glavin. N.p.: Cambridge University Press.

Stam, Robert. 2000. “Beyond Fidelity: The Dialogics of Adaptation.” In Film Adaptation, edited by James Naremore. N.p.: Rutgers University Press.

Williams, Sally. 2011. “Mud, dust and Dickens: Great Expectations at BBC One.” The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/tvandradio/8940068/Mud-dust-and-Dickens-Great-Expectations-at-BBC-One.html.

Filmography

Great Expectations. (1946) Directed by David Lean. UK: Cineguild

Great Expectations. (1998) Directed by Alfonso Cuarón. USA: 20th Century Fox

Great Expectations. (2011) Executive Producer Anna Pivcevic. UK: BBC

Great Expectations. (2012) Directed by Mike Newell. UK: BFI / BBC.

Great Expectations. (2023) Executive Producer Steven Knight. Featuring Olivia Colman. UK: BBC / FX.