Abstract

Environmental degradation and one of its effects, global warming, have worsened the inequalities between the rich and the poor among people and nations. The Catholic Church has demonstrated its deep commitment to social justice visibly since the Vatican II, while the most recent Encyclical, Laudato Si1, offered by Pope Francis moves the Church in an unprecedented manner toward the coupling of sustainability and religion to address global inequalities.

This paper features a few important dimensions of inequalities to heighten the urgency of global social justice work. It then reviews documents connected to sustainability in Catholic social teaching, with an emphasis on Laudato Si by Pope Francis.

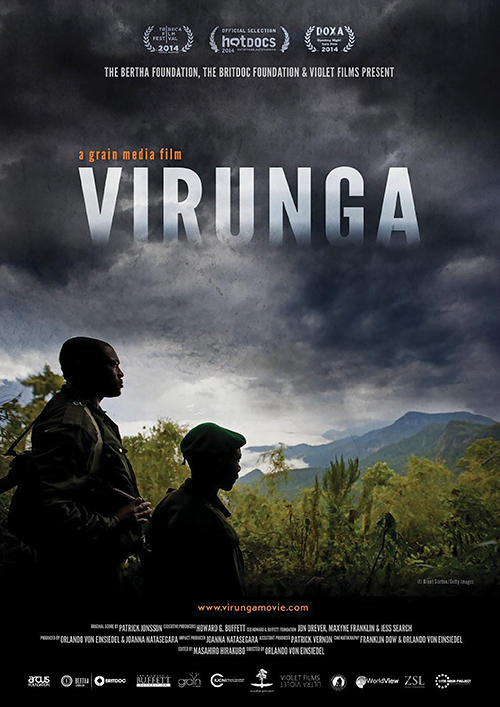

Finally, through a brief analysis of a contemporary documentary film, “Virunga” (2014),2 which focuses on a crisis that recently occurred in the Virunga National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo, this paper illustrates an impactful and effective way to articulate global inequality and mobilize coalitions to protect people, creatures and land against violence and environmental degradation.

Social documentaries, in general, represent voices for justice and the common good shared by all major religions, and the documents of the Catholic Church highlighted in the paper offer a concrete trajectory for global justice that we see in cinematic form.

Keywords: Catholic Social Justice, Documentaries for Social Justice, Virunga, Environment

Introduction

We live in a world where global inequalities between the developed and the developing countries are manifested in extreme gaps in food, water, shelter, access to energy, health care, education, and other sociopolitical and financial infrastructures.

For more than 50 years since Vatican II, the Catholic Church has been addressing these inequalities. However, environmental degradation and global warming have reached such an extent that they have not only worsened the gaps between the have’s and have-not’s, but also posed imminent threat to our common existence as human beings. To secure coalitions among communities who are committed to making a difference in bridging the inequality gaps with an emphasis on sustainability, in the first section of this paper, I will provide selective data to illustrate global inequalities. Next, I will reference some of the most impactful documents offered by the Catholic Church, touching on issues related to the environment and human development. In the third section of this paper, I will connect the Catholic teachings to an outstanding documentary film released in 2014, Virunga, illustrating an impactful and effective way to articulate global inequality and mobilize coalitions to protect people, creatures and land against violence and environmental degradation.

I. International Inequalities and Injustices

Before getting into the documentary and the catholic social justice documents, though, we must understand that they will have to be read against the backdrop of significant global realities, which appear to reflect deep inequalities and injustices.

Without meaning to be exhaustive, what is offered here highlights imbalance of power and uneven vulnerability between nations. Valuable information is provided on these and other issues by the monthly journal, New Internationalist, and by major development agencies such as the World Bank and the World Development Movement (WDM).

Energy and Infrastructure:

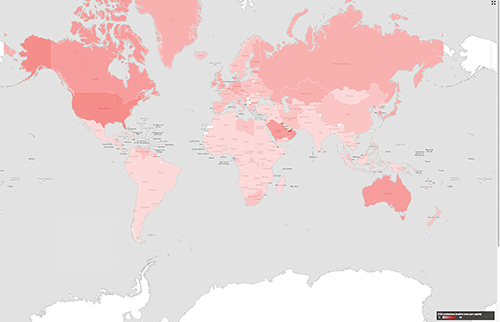

The three regions of the world, Asia, USA and Western Europe, which between them consume 71 per cent of the world’s oil, have only 6 per cent of the estimated reserves.3 If we compare CO2 emissions between the USA and a developing African country, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, the USA has 17.6 CO2 emissions (metric tons per capita - population, total 316.1 millions) and Congo has 0.0 CO2 emissions (metric tons per capita - population, total 67.51 millions).4 North America, Australia and most of Europe have the highest access to Internet. Comparing the US with Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo has 2.2 Internet users (per 100 people) meanwhile the US has 84.2 users (per 100 people) between 2010-2014.5

Image 1 – CO2 Emissions in the World (metric tons per capita) – World Bank Indicators – 2014

Food production and distribution:

In developing countries the share of land that is arable is above 40% and the least developed countries are at 39.8% (according to the UN classification). Agriculture provides the main source of income for more than 2 billion people living in undeveloped countries6. However, large agricultural companies from developed countries control the world agricultural trade without supporting the economy of the undeveloped countries.

Water:

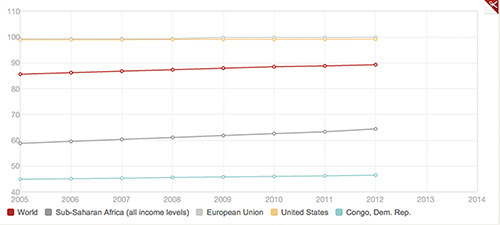

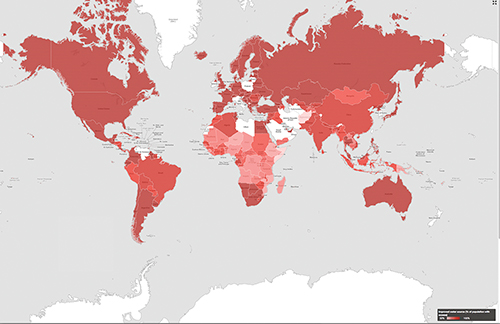

In 2014 more than 50% of the population in most of Africa did not have access to any source of improved drinking water. The lower percentages are in Papa New Guinea with 40% in 2010-14, the Democratic Republic of Congo with 47%, Mozambique with 48%, Madagascar with 50% and many others in Sub-Sahara Africa, with less than 60% having access to safe water supplies. By contrast the European Union and United States supply 99% of their population with access to clean water, with world totals at 89.3%7.

Image 2 – Improved water source graphic (% of population with access) – World Bank Indicators – 2014

Image 3 – Improved water source map (% of population with access) – World Bank Indicators – 2014

Gross Domestic Product, PPP:

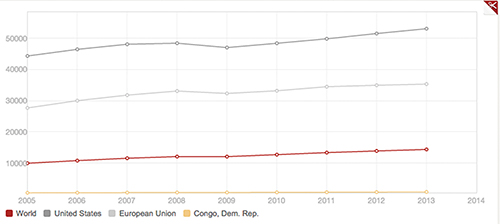

GDP per capita based on purchase power parity (PPP) rates gives us a good indication of the gap between developed and developing countries. The world average is $14,400 (WB, 2013), the European Community is $35,300, and the USA is $53,000 (see WB graph.) The majority of Sub-Sahara countries are under $2,000, with the Democratic Republic of Congo at $809 in 20138.

Image 4 – GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) – World Bank Indicators – 2014

What this brief review tells us is quite clear: less developed countries are excluded from full and meaningful participation in the life of the global community in ways that violate the common good and solidarity between nations all over the world. The data bear it out. But it is more than a simple fact. It is a deep violation of our most fundamental values. The toll it takes on life on this planet reaches beyond what statistics in isolation can communicate.

This is why, if we are to mount effective movements for social justice and reallocation of resources, we must find other, deeper, and more impactful ways to talk about real crises in the here and now. We must overcome real crises mobilizing solidarity among countries. This process could lead to the fostering of a sustainable environment where the sharing of natural resources among countries becomes the sign of the new social justice. Doing so can responsibly answer the “cry of the earth and the cry of the poor” as Pope Francis puts it in his latest Encyclical, Laudato Si.

Catholic Documents that address environment and development issues

Catholic social teaching on development has closely followed post-war theories of modernization, dependency, and global capitalism. Pope John XXIII was the first pope to seriously consider development issues and in the four decades since, there has been considerable advancement in Catholic teaching.

All of the existing documents and encyclicals of the Catholic Church from 1961 up to the present link human development with sustainability. However with his latest Encyclical, Laudato Si, Pope Francis articulates a highly visible connection between human development, environment and spirituality in ways that go substantially beyond what remains opaque in the earlier Church documents. For the ease of reference, a summary of Catholic Church documents related to social justice and the environment is compiled in Appendix A. For the purpose of this paper, however, I shall address primarily Laudato Si through what Pope Francis offers as a global change project that emphasizes an integral ecology, a new lifestyle, and “a generous and worthy creativity which brings out the best in human beings” (§211).

The Encyclical, Laudato Si, is divided into six chapters. It begins with a presentation of the current situation based on the best scientific findings available today. Next, Pope Francis offers a review of the Bible and the Judeo-Christian tradition. The root of today’s problems in technocracy and in an excessive self-centeredness of the human being is analyzed. The Encyclical proposes an integral ecology, which clearly respects its human and social dimensions, however, such an ecology is inextricably linked to the environmental question. In this perspective, Pope Francis suggests to initiate an honest dialogue at every level of our social, economic and political life. Such a dialogue has the capacity to build a more transparent decision-making processes because no project can remain effective if it is not animated by a responsible conscience.

Laudato Si proposes that an authentic ecological study cannot exist without a social approach: “. . . it must integrate questions of justice in debates on the environment, so as to hear both the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor” (§ 49). The earth that we inhabit cannot be dissociated from the poor that live in it. The poor, in other words, should be the center of any environmental change projects. Pope Francis’s holistic approach re-signifies social teaching from a Church that for so long had studied creation from a purely ontological and theological perspective, which dissociates creation from nature, time and space and the eruption of sufferings in humans and the nature. The close coupling of the “cry of the poor” and the “cry of the earth” in the same sentence is remarkable. It urges that environmental justice and world peace can only be achieved when human beings are empowered to view the earth as our common home. Peace and justice can only be achieved when we include the care for ecology into our discourse on the common good (§225).

Pope Francis concludes his Encyclical ‘by calling attention to the special and essential significance of justice in the biblical message – that of protection of the weak and of their right, as children of God, to the wealth of creation’ and it called for the restoration of ‘social justice through a distribution of land ownership carried out in a spirit of solidarity’ (§§59-61).

Laudato Si reflects Pope Francis’s authentic concerns with global problems that plague humans, creatures and the nature. Informed by the best facts available to us, Pope Francis encourages that, when rightly understood, science, morality, ethics, and religion can and must join hands to care for an integral ecology now and into the future.

In the next section of the paper, I shall illustrate powerful ways holistic messages of need and hope as articulated by Pope Francis can be carried through a documentary film to audiences all over the world and enable us to rise above the abstractions of numbers and words to make deep and meaningful changes.

Developmental Sustainability in “Virunga” (2014)

Virunga (2014) is an Oscar nominated (2015)9 documentary that shines a bright light onto the intimate connections between world and domestic politics, the fragility of our eco-system and the hope for needed social change through powerful cinematic language / form.

Established in 1925, Virunga National Park10 is the first national park in Africa. It has been designated as an UNESCO world heritage site since 1979. The changes in sovereignty from Belgian colonization (1908-1960) to Congo’s independence, domestic political shifts from Zaire (1971-1997) to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (1997 – present), regional wars with the involvement from neighboring countries, and most recently the threat from SOCO11, a transnational oil and gas exploration/production firm, have contributed to the vicissitudes of Virunga’s well-being.

Image 5 – African map showing SOCO’s area of operations within Virunga N.P. – Virunga (2014)

The park’s rangers, in the midst of violent poaching incidents as well as recurring wars and the threat of oil exploration/production, thus have evolved into a special role the guardians and protectors for the wild lives and the ecological integrity of the park. Since 1996, because of their deep commitment, more than 140 Virunga rangers lost their lives.

The documentary features Virunga as one of the most bio-diverse regions in the world and home to half of the last 880 remaining critically endangered mountain gorillas12. Sadly however, in the beginning of the documentary, the viewers saw the bodies of 9 gorillas being carried by villagers into town for burial (some were over 400 pounds), having been slaughtered by poachers.

A gorilla orphanage was subsequently shown, a place where four young gorillas that had survived different incidents of slaughter, were housed. Andre Bauma, a Virunga ranger and the caretaker of the gorilla orphans, became one of the protagonists of the documentary. In fact, he was the gorilla orphan’s father, friend, and keeper. He embodied Saint Francis’s “original innocence” (p. 28) in total harmony with creatures. He embodied the paradigm of love over greed. As the M23, a rebel group, approached the Virunga National Park, Bauma refused to leave, to abandon the gorilla orphans. He eloquently put it: “You must justify why you are on this earth - gorillas justify why I am here, they are my life. So, if it is about dying, I will die for the gorillas.13” In other words, he chose to die for life if necessary.

Image 6 – André Bauma with one of the orphan gorillas in the documentary – Virunga (2014)

In Laudato Si, Pope Francis touches on the appreciation of beauty as an essential component of education to foster the mindsets for deep change, “If someone has not learned to stop and admire something beautiful, we should not be surprised if he or she treats everything as an object to be used and abused without scruple” (§ 215).

Virunga’s cinematography brings beauty to the beholders – elephants roaming along river banks in quiet joy, cranes pushing away silvery reeds to fly towards the clouds, the night sky - black velvet dotted with limpid stars as God’s eyes, and the ever expanding majestic landscape that humbles humans and creatures alike.

The beauty of connections between humans and creatures was epitomized in one of the film’s last scenes: After a dangerous armed conflict with the M23, the rangers hiked to the gorilla habitat to assess the carnage; they breathed a sigh of relief to find a gorilla family, lying in tranquility together in the bush; and a three-month old baby gorilla on its mother’s bosom, out of curiosity, stretched to touch the tip of the park director’s shoe. The trusting touch by the infant gorilla inspired a profound sense of purpose in the director, in the rangers and in the audiences.

Nourished by such divine beauty in nature and between creatures around the Virunga National Park, viewers could no longer stomach the violence against creatures and humans on the land, and the imminent degradation of this sanctuary inflicted by the SOCO International. Changes -- deep, real and global in scale -- became the obvious and fitting solution to the crises documented by Viruga’s beautiful, raw and investigative reporting.

This was consistent with Laudato Si’s call for change: “An interdependent world not only makes us more conscious of the negative effects of certain lifestyles and models of production and consumption which affect us all; more importantly, it motivates us to ensure that solutions are proposed from a global perspective, and not simply to defend the interests of a few countries. Interdependence obliges us to think of one world with a common plan” (§ 164).

The release of Virunga in major film festivals and its official screenings on the Capitol Hill, the British and the EU Parliament, the African Union and the UN, unleashed not only outcries but also concerted global efforts to stop SOCO’s prospecting in the park.

The film’s persuasive power was further enhanced, sadly, because Prince Emmanuel de Merode, the Director of the Virunga National Park, whose shoe was touched by the baby gorilla, was seriously wounded in a roadside ambush on April 15, 2014. Thankfully, Emmanuel survived the attack. He encouraged the film director, via a phone conversation, to continue with the global distribution of the movie.14

Image 7 – Emmanuel de Merode with mountain gorillas at Virunga N.P. – Virunga (2014)

Using investigative reporting through undercover footage, this documentary shows the determination and courage of these few park rangers who protected the National Park from poachers, regional wars, and life threats from SOCO contractors who intended to drill inside the park. These life threats were later reported and substantiated by different Human Rights organizations, such as the World Wild Fund (WWF) and Human Rights Watch (HRW). HRW wrote a 40-page report at the conclusion of their investigation15 and WWF took SOCO to court and then legal mediation in London in order to stop their oil exploration at the Virunga National Park. They were successful in their litigation and on June 11, 2014 SOCO, in a joint statement with WWF, said, “The company commits not to undertake or commission any exploratory or other drilling within Virunga National Park unless UNESCO and the DRC government agree that such activities are not incompatible with its World Heritage status” 16.

The Virunga documentary film succeeded in bringing to light a new social awareness of the mountain gorillas and their courageous guardians, the park rangers. Their environmental struggle reached the governments of Europe, Africa, and the US and many high-profile people, such as Bishop Desmond Tutu of South Africa, and Howard Buffet in the U.S. Leading nature conservation / non-profit organizations, as a consequence, were able to collect more than 700,000 signatures in order to halt oil exploration in this UNESCO world heritage site. The international online distribution of Virunga through Netflix17 further disseminated this work of environmental social justice and its message calling for a delicate balance and sustainable economical development in one of the poorest regions on earth.

Image 8 – Virunga documentary, a Netflix release – Virunga (2014)

De Merode, the Director of the Virunga National Park, was able to affect change through a series of initiatives relying on a diverse coalition among127 local institutions from the private sector, civil society and government agencies committed to the sustainable development of the park’s resources through tourism, electric power infrastructure in rural areas, sustainable fisheries and agriculture. These initiatives aim to generate employment for 80,000 to 100,000 people in the post-war communities living around the national park.

Virunga is an effective example of how a documentary can raise the level of awareness and social consciousness in matters of ecological and sustainable human development. World distribution through film festivals and Netflix allowed news media organizations to report on the story18. The environmental organizations from the British, Belgium and French governments facilitated the documentary’s screening to the European, African and US governments, furthering the insight into Congo’s environmental and developmental issues among the political leaders of these nations.

Image 9 – André Bauma with one of the orphan gorillas in the documentary – Virunga (2014)

Conclusion

Pope Paul VI concluded his encyclical Populorum Progressio with the idea that, “the new name for peace is development” (§87). Without balanced and authentic human development we’ll be in the presence of social injustice, which could lead to unrest, conflict and in extreme cases, war. Pope Francis in his encyclical Laudato Si presents a similar and focus conclusion when connects ecological development with a social approach. We must integrate the questions of justice in conversations on the environment “so as to hear both the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor” (§49). A fair and equitable economic and human development leads to stability and community growth in our “common home” (§232).

Virunga shows that the exploration of natural resources in the Virunga National Park, without respecting the delicate eco-system of the region could lead to conflict, population displacement, violence and potentially to a regional war. However, if local and regional organizations respect their own environment, it could lead to authentic and sustained human development. De Merode, the Director of the National Park, was able to prove through his initiatives that balanced economical development that respects the vulnerable eco-system brings employment to the region while still ensuring the safety of local animals and a period of regional peace.

One of the important roles of documentary films is to feature voices for justice issues, shared by all major religions that humanity is valued as part of the common good. The written documents of the Catholic Church on the Environment as well as documentaries with social justice themes, like Virunga, express environmental and developmental concerns. They both pose ethical questions and propose kindred solutions.

The Catholic Church proposes a concrete trajectory for global justice on Environmental sustainability in written form while social documentaries use cinematic forms, yet they both seek the same goal of social justice.

Image 10 – Virunga National Park – Democratic Republic of Congo.

Appendix 1

1. Mater et Magistra (John XXIIl, 196I)

John XXIII was the first pope to insist that ‘with the growth of the economy, there occurs a corresponding social development’ (§73). He urged that justice and humanity required that ‘richer countries come to the aid of those in need (§161) without seeking to dominate with new forms of colonialism (§§171-172).

2. Pacem in Terris (John XXIII, I963)

Pope John’s encyclical letter ‘on establishing universal peace in truth, justice, charity and liberty’ spoke, for the first time, to ‘all men of good will’. He insisted on the equal dignity of all and that there was no justification for racial discrimination (§44).

3. Gaudium et Spes (Vatican II, I965)

The Council Fathers noted that while economic development ‘could diminish social inequalities’ if properly guided and coordinated, ‘all too often it serves only to intensify the inequalities ... (and) the very peace of the world can be jeopardized in consequence’ (§§63, 83).

4. Populorum Progressio (Paul VI, 1967)

Pope Paul’s encyclical was the first to focus specifically on the theme of ‘the development of peoples’. While acknowledging some of the benefits brought by colonizers in the past, the Pope was alarmed at the widening of the gap between rich and poor peoples, that some have food surpluses while others hunger, that the hardships experienced by many farmers were ‘undeserving’, and that ‘there is also the scandal of glaring inequalities not merely in the enjoyment of possessions but even more in the exercise of power’ (§§7-9).

5. CELAM II at Medellin (1968)

The Latin American bishops developed Pope Paul’s vision in the particular circumstances of Latin America.19 They affirmed the importance of both individual conversion and structural change. ‘We will not have a new continent without new and reformed structures, but, above all, there will be no new continent without new men, who know how to be truly free and responsible according to the light of the Gospel’. Among such new structures must be those promoting the participation of all people, especially the lower classes. The bishops denounced both liberal capitalism and Marxist collectivism because ‘both systems militate against the dignity of the human person’.

6. Octogesima Adveniens (Paul VI, 1971)

In this apostolic letter Pope Paul wrote that he was appalled by the ‘flagrant inequalities (which) exist in the economic, cultural, and political development of the nations’ (§2) and appealed for more justice globally. He presented a valuable checklist for action.

7. Justice in the World (Synod of Bishops, 1971)

In their document the Synod bishops produced what is probably the most quoted statement about the centrality of “justice seeking” in the lives of Christians:

Action on behalf of justice and participation in the transformation of the world fully appear to us as a constitutive dimension of the preaching of the Gospel, or, in other words, of the Church’s mission for the redemption of the human race and its liberation from every oppressive situation.

8. Evangelii Nuntiandi (Paul VI, 1975)

Reflecting the emergence of liberation theology, Pope Paul taught that Jesus’ mission was ‘liberation from everything that oppresses man which is above all liberation from sin and the Evil One, in the joy of knowing God and being known by Him’. He required struggle and ‘a radical conversion, a profound change of mind and heart’ (§§9- 10).

9. Economic justice far All (US Bishops, 1986)

While this pastoral letter primarily addressed domestic economic issues it also recognized that ‘the pre-eminent role of the United States in an increasingly interdependent global economy is a central sign of our times’ (§10). They viewed exclusion created by unjust elites and unjust governments as ‘forms of social sin’ (§77).

They concluded by calling ‘for a U.S. international economic policy designed to empower people everywhere and enable them to continue to develop a sense of their own worth, improve the quality of their lives, and ensure that the benefits of economic growth are shared equitably’ (§§288, 290-292).

10. International Debt (Pontifical Justice and Peace Commission I986)

This document offered an ethical approach to the international debt question and a framework for the consideration of the responsibilities of all the relevant actors. In particular it advocated seeking solutions to the debt crisis ‘in a spirit of dialogue and mutual comprehension’ according to the ethical principles of solidarity, which recognized interdependence and equal dignity, the sharing of responsibility, the equitable sharing of the necessary sacrifices, and the requirements of social justice. In emergency situations, the document urged ‘an ethics of survival’ and was critical of some IMF solutions ‘imposed in an authoritarian and technocratic way without due consideration for urgent social requirements’.

11. Sollicitudo Rei Socialis (John Paul II, I987)

Pope John Paul II insisted that authentic development ‘would respect and promote all the dimensions of the human person’, social, political, cultural and spiritual as well as economic (§§1, 9, 15). Apart from poverty, John Paul II also drew attention to the prevalence of illiteracy and discrimination, the housing crisis, unemployment and underemployment, and the question of international debt (§§15, 17-19).

12. Centesimus Annus (John Paul II, 1991)

This encyclical celebrated one hundred years of Catholic social teaching since Rerum Novarum. Written two years after the collapse of Soviet totalitarianism in Central and Eastern Europe, it analyzed the spiritual inadequacies of atheistic Marxism, regretted the post-war division of Europe and called for ‘assistance from the countries of Europe which were part of that history and which bear responsibility for it, (since this) represents a debt in justice’ (§28).

13. Tertio Millennia Adveniente (John Paul II, 1994)

This encyclical looked forward to the third millennium and offered a spiritual reflection and invitation to Catholics. It focused on the biblical theme of jubilee and emancipation from debt and slavery and the restoration of equality and social justice (§§11- 13). In this spirit John Paul II called on ‘the European nations to make a serious examination of conscience, and to acknowledge faults and errors, both economic and political, resulting from imperialist policies carried out in the (nineteenth and twentieth) centuries vis-a-vis nations whose rights have been systematically violated’ (§27).

Endnotes

1 Francis, Pope 2015, On Care for our Common Home (Laudato Si), http://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclica-laudato-si.html

2 Virunga (2014) takes up issues of inequalities in matters of energy, eco-system and human development. It uses media language to focus on social justice issues in a microcosm, the Virunga National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

3 New Internationalist 355, June 2001: 14; 36I, October 2003: 12, 18-19.

4 World Bank, 2014. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.ATM.CO2E.PC.

5 World Bank, 2014. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.P2/countries?display=default.

6 World Bank, 2014. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.AGR.EMPL.ZS/countries/1W-US-CD-XC?display=default.

7 World Bank, 2014. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.H2O.SAFE.ZS/countries/1W-EU-US?display=graph

8 World Bank, 2014. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD/countries/1W-US-EU-CD?order=wbapi_data_value_2013%20wbapi_data_value%20wbapi_data_value-last&sort=asc&display=default.

9 Virunga received 17 nominations and won 15 awards - IMDb. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt3455224/awards?ref_=tt_awd.

10 Virunga National Park official site: https://virunga.org

11 SOCO International: http://www.socointernational.com/home

12 WWF report on Mountain Gorillas: http://www.worldwildlife.org/species/mountain-gorilla

13 http://www.imdb.com/title/tt3455224/trivia?tab=qt&ref_=tt_trv_qu.

14 http://moveablefest.com/moveable_fest/2014/11/orlando-von-einsiedel-virunga.html.

15 http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/06/04/dr-congo-investigate-attacks-oil-project-critics.

16 http://www.socointernational.com/virunga-related-press-releases. Also many International news agencies as the Gardian posted the conclusion of the litigation: http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/jun/11/soco-oil-virunga-national-park-congo-wwf.

17 http://www.netflix.com/WiMovie/80009431 .

18 Reuters report: http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/11/07/us-film-netflix-virunga-idUSKBN0IQ2OB20141107. TheGardian: http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/jun/11/soco-oil-virunga-national-park-congo-wwf . Global Witness: https://www.globalwitness.org/blog/10-questions-uk-oil-company-soco-international-must-answer-virunga-documentary-nominated-oscar/

19 CELAM II 1979: Justice, §§3, 7,10; Poverty §§9-10.

Bibliography

CELAM II, 1979, The Church in the Present-Day Transformation of Latin America in the Light of the Council: II Conclusions (Medellin). Washington, DC: USCCB.

Francis, Pope 2015, On Care for our Common Home (Laudato Si), http://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclica-laudato-si.html

John XXIII, Pope 1961, Christianity and Social Progress (Mater et Magistra), in O’Brien, David and Shannon, Thomas (Edit.), Catholic Social Thought, Maryknoll, New York, 2010, pp.85-134

John XXIII, Pope 1963, Peace on Earth (Pacem in Terris), in O’Brien, David and Shannon, Thomas (Edit.), Catholic Social Thought, Maryknoll, New York, 2010, pp.137-170

John Paul II, Pope 1981, On Human Work (Laborem Exercens), in O’Brien, David and Shannon, Thomas (Edit.), Catholic Social Thought, Maryknoll, New York, 2010, pp.378-421.

John Paul II, Pope 1987, On Social Concern (Sollicitudo Rei Socialis), in O’Brien, David and Shannon, Thomas (Edit.), Catholic Social Thought, Maryknoll, New York, 2010, pp.424-468.

John Paul II, Pope 1991, On the Hundredth Anniversary of Rerum Novarum (Centesiums Annus), in O’Brien, David and Shannon, Thomas (Edit.), Catholic Social Thought, Maryknoll, New York, 2010, pp.471-523.

Paul VI, Pope 1967, On the Development of People (Populorum Progressio), in O’Brien, David and Shannon, Thomas (Edit.), Catholic Social Thought, Maryknoll, New York, 2010, pp.253-277.

Paul VI, Pope 1971, A Call to Action on the Eightieth Anniversary (Octogesima Adveniens), in O’Brien, David and Shannon, Thomas (Edit.), Catholic Social Thought, Maryknoll, New York, 2010, pp.280-303.

Paul VI, Pope 1975, Evangelization in the Modern World (Evangelii Nuntiandi), in O’Brien, David and Shannon, Thomas (Edit.), Catholic Social Thought, Maryknoll, New York, 2010, pp.321-368.

Second Vatican Council, 1965, Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et Spes), in O’Brien, David and Shannon, Thomas (Edit.), Catholic Social Thought, Maryknoll, New York, 2010, pp.174-250.

Synod of Bishops, 1971, Justice in the World, in O’Brien, David and Shannon, Thomas (Edit.), Catholic Social Thought, Maryknoll, New York,2010, pp.305-318.

U.S. Catholic Bishops, 1986, Economic Justice for All, in O’Brien, David and Shannon, Thomas (Edit.), Catholic Social Thought, Maryknoll, New York, 2010, pp.689-806.

Filmography

Virunga. (2014). Directed by Orlando von Einsiedel, UK: Grain Media. Netflix