Abstract

The film noir style is easily recognizable for its technical innovations and aesthetic choices, which represent a clear departure from the classical Hollywood style of the 1930s. This shift is also evident in the realm of film scoring, where a new generation of composers sought to reflect the emotional and moral ambiguity, as well as the shadowy atmospheres, of noir cinema through music that diverged from the traditions of 19th-century European Romanticism. This article focuses on the aural dimension of film noir, specifically examining the music that accompanies the first flashback sequences in three seminal films: Double Indemnity (1944), scored by Miklós Rózsa; Laura (1944), scored by David Raksin; and Sunset Boulevard (1950), scored by Franz Waxman. The analysis explores how each composer evokes memory through sound by examining harmony, rhythm, orchestration, and diegesis during these temporal transitions. By juxtaposing musical scores with the corresponding dialogue from key scenes, this study aims to deepen our understanding of the role of music and sound in film noir, inspired by the concept of the integrated soundtrack.

Keywords: Flashback, Film noir, Film score, Integrated soundtrack, Music analysis.

Prelude to the Past

In the Hollywood of the 1940s, the specific style or genre of films emerged, later designated as film noir. It was characterized by particular lightning techniques, high contrast, dark environment and themes, cynicism and existentialism, morally ambiguous heroes, femmes fatales, intricate plots, a frequent use of an all-knowing narrator, and a narrative style filled with flashbacks.

The common viewer is familiar with the notion of a flashback as a frequent narrative device in cinema, altering the temporal line, offering the historical context or diving into the memory of an individual character’s subjective experience. The approaches to creating a flashback in cinema range from camera movements, special effects, editing techniques to sound effects and musical cues. It is precisely in these sonic and musical characteristics of a flashback that this paper will be focused on, analyzing examples in three noir films – Double Indemnity (1944), Laura (1944) and Sunset Boulevard (1950).

The previously mentioned characteristics of film noir evolved hand in hand with new approaches to film scoring that brought about a more modern sound, further highlighting the ability of music to evoke emotion, memory and building of an atmosphere. Interestingly it is precisely this sound component, the holistic approach to the musical aspect of the film noir that is lacking in film studies. As Richard Ness bluntly puts it, the “critics who have defined the basic characteristics of noir films have failed to take into account that noir has a specific sound as well” (Ness 2008, 52).

One of the indispensable names in film scoring and redefining of Hollywood musical landscape in mid twentieth century, Miklós Rózsa, composed the score for Double Indemnity, the first film in our analysis. Here, the flashback is introduced almost right at the beginning of the film and the change in the music that comes with it opens the gate to the narration of past events. In similar manner, Sunset Boulevard starts in the darkest point of the story, and the flashback that happens in the first couple of minutes of the film takes us as far back in the narrator’s memory as to help us situate and understand the plot we are about to witness. Here, the musical gestures written by Franz Waxman trigger the passage to the past timeline. Finally, a more unique approach in usage of the flashback is visible in Laura, scored by David Raksin. Throughout the film, we are pushed back in time several times, and the different variations of the main theme work as an emotional and memory device to connect the narrative while it jumps between the present and the past. Thus, from the Franz Waxman’s high pitch string section trills, through Miklós Rózsa’s propelling melody in a violin section to David Raksin’s variations on a single theme1, all these approaches to aurally stimulate the spectator through a flashback will be at the center of this analysis, at the same time trying to identify the musical identity of the film noir.

The use of flashbacks can be traced back to the early years of cinema. It can be described as “an image or a filmic segment that is understood as representing temporal occurrences anterior to those in the images that preceded it” (Turim 1989, 1). With the advent of sound in cinema, we observe the steady evolution which multiplies the creative possibilities in design and implementation of these narrative devices, especially due to the introduction of voice-over narration and the incorporation and manipulation of sound elements which allowed different ways of creating narrative retrospectives. The decades of the 1940s and 1950s were particularly important, because flashbacks proliferated in a different number of iconic cinematic works that would later fall into the noir category.

Analysis of flashbacks in three noir films

Double Indemnity (1944)

Later I was summoned to his [Musical Director] office where, in the presence of his assistant, he reprimanded me for writing “Carnegie Hall” music which had no place in a film (…) De Sylva [artistic director of the studio], however, began praising the music to the skies, saying that it was exactly the sort of dissonance, hard-hitting score the film needed. (Rózsa 1982, 121 - 122)

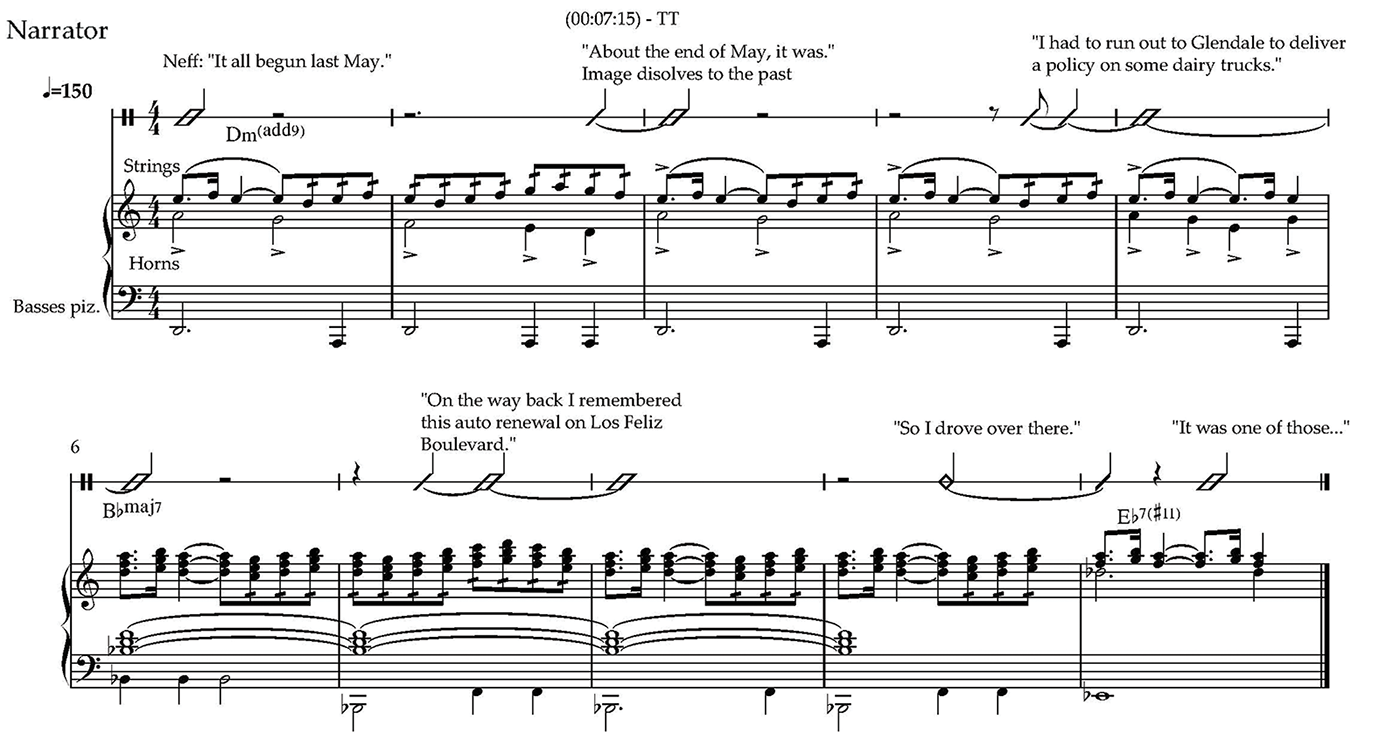

Walter Neff, an insurance salesman, badly injured – later revealed to be from a gunshot wound – is seated at his boss’s desk, recording a murder confession into a recorder (Figure 1). Likely seeking some form of redemption, he describes a series of events that led him to commit the crime. In Double Indemnity, the shift to another temporal line is made explicit through Neff’s words. After a long pause to grab a cigarette – seemingly to gather his thoughts – he continues: “It all began last May. Around the end of May, it was.”

This statement carries the weight of a once upon a time… moment. At that exact instant, Rózsa’s cue begins, propelling the narrative into memory, into a kind of fantasy world. No sound effects accompany the transition – no car engine, no children playing in the street, no ambient noise whatsoever, trying to mimic the reality of the new scene – only the narrator’s voice and the music.

Despite its relatively fast and energetic pace, the music remains “lightly textured” (Brown 1994, 125), resembling a minimalist score. It follows a repetitive pattern, built on the first five pitches of the minor mode, played by high midrange strings over a steady tonal center that remains static until the sixth bar, where it shifts to the sixth degree of the mode (Figure 2). The cue never “approaches anything resembling a musical closure” (Brown 1994, 125). As Schickel observed, Double Indemnity’s score is “artfully repetitive, it is insinuating rather than overpowering” (Schickel 1992, 65). The main character arrives by car at an old Spanish villa situated atop a hill, offering a panoramic view of a Californian town. After parking by the house, he walks toward the front door. It is only when the doorbell rings and Walter Neff’s voice ceases its narration – shifting instead to become diegetic within the new timeline – that we are pushed out of this dreamlike time-travel sequence.

Once Neff, from the past timeline, gains his own voice, what initially seemed predetermined, begins to feel unpredictable. The spectator witnesses a series of actions and consequences that, while inevitable, remain surprising.

This theme, titled The Conspiracy, recurs several times throughout the film, reinforcing Neff’s narration and providing “affective support of sorts to mark the transition between Neff’s voice in sync with the visuals and his narration as a voice-over” (Brown 1994, 126). It also appears, underscoring events marked by “a dissolve in the visuals marking the transition from one sequence to the next” (Brown 1994, 126). For these reasons, The Conspiracy is oftentimes referred to as the narration theme.

Laura (1944)

The theme is never allowed to come to a resolution, which maintains its sense of mystery: like the woman it describes, it is, in some sense, a wandering ghost, musically diaphanous, shimmering, ever-changing. (Kirgo 2013)

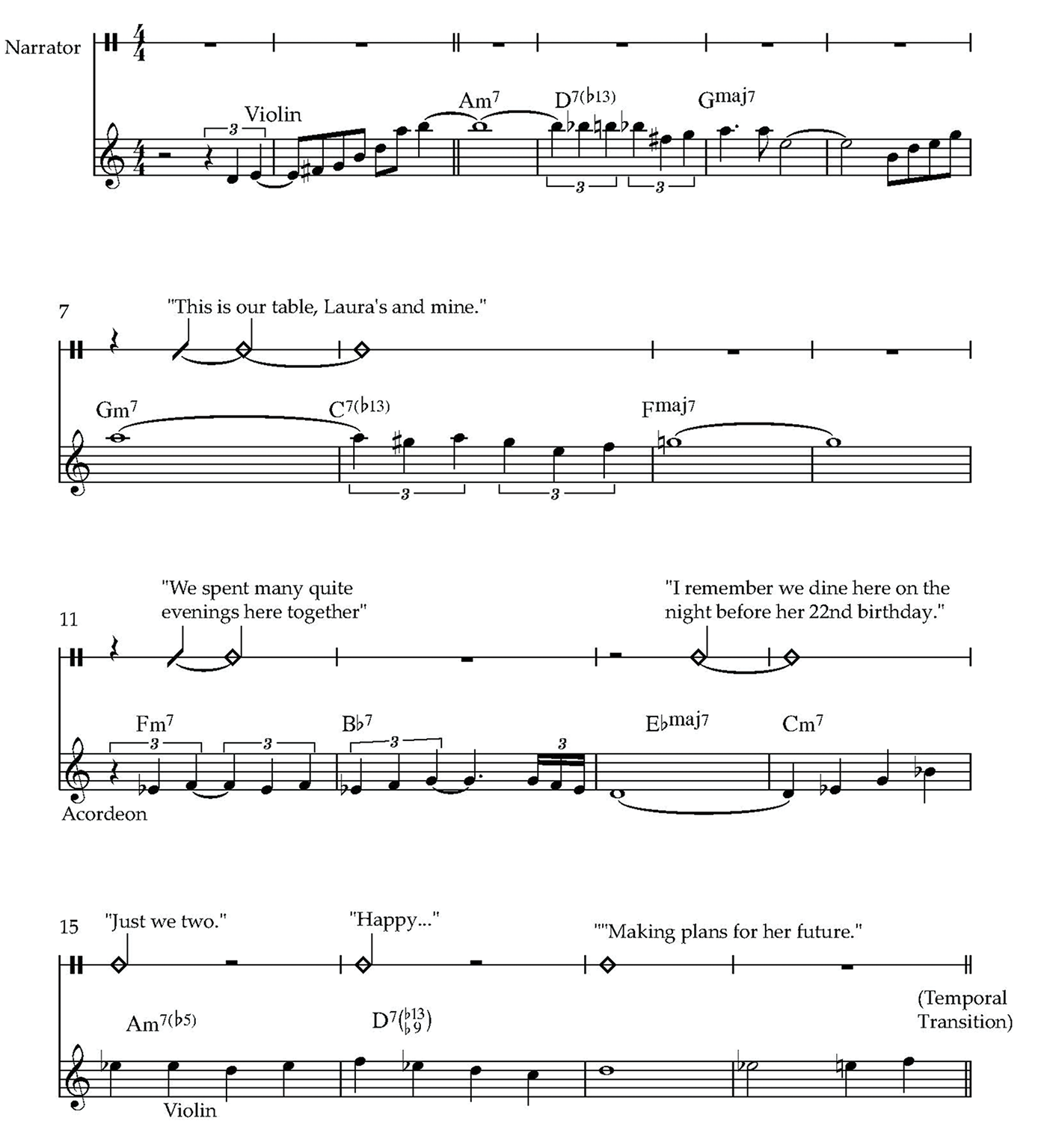

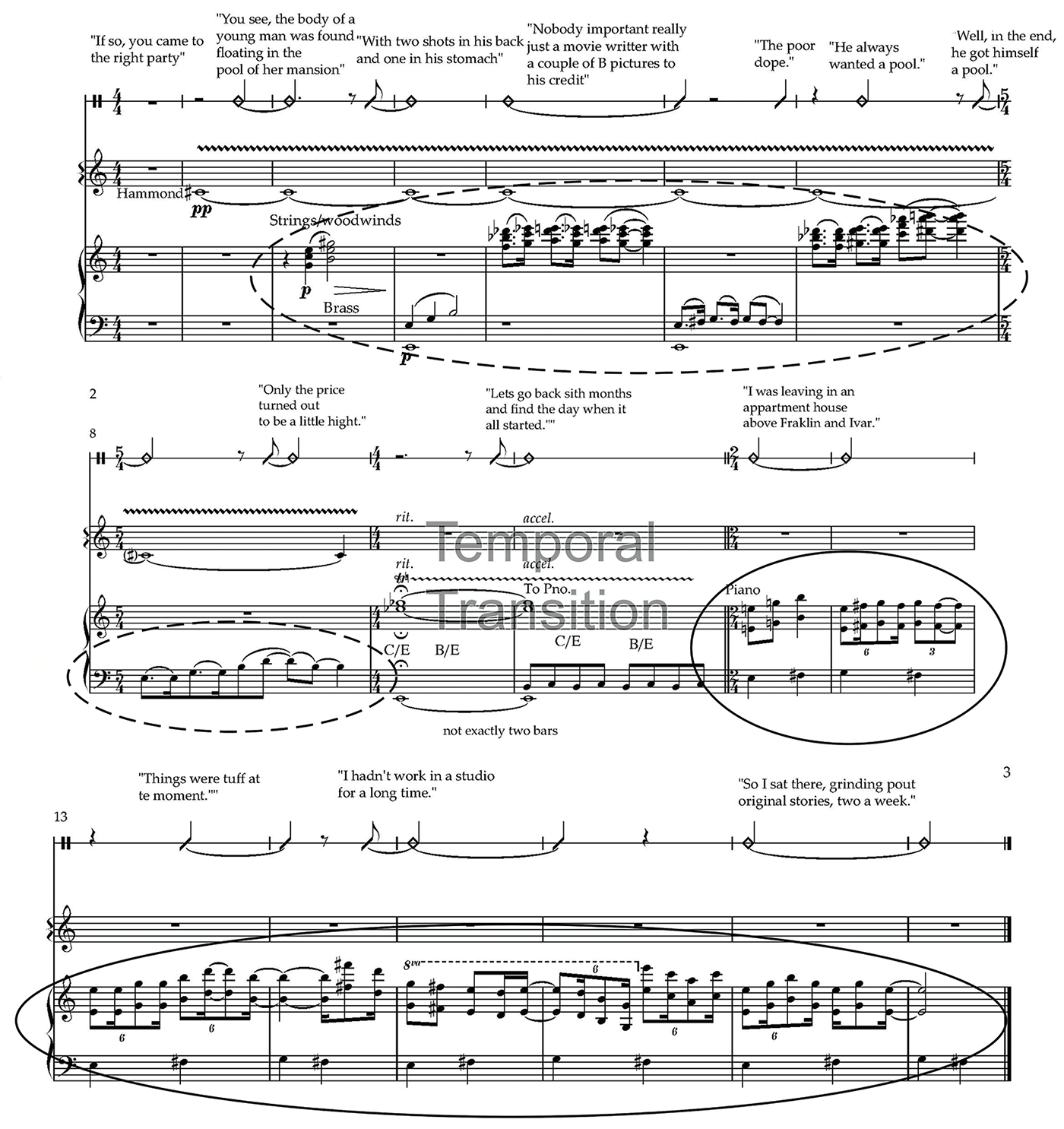

“This is our table. Laura’s and mine.” – says the newspaper columnist Waldo Lydecker to detective McPherson when they meet in a restaurant (Figure 3). The scene starts by showing a small ensemble composed of piano, violin and accordion, they are performing the main theme of the movie, and this music appears to us as source music or diegetic. While the band plays, the camera travels through the restaurant until we are back to the protagonists.

Waldo Lydecker goes on saying “We spent many quite evenings here together…” and, as nostalgia takes over Waldo’s words, the camera moves towards and the image dissolves. It is accompanied by a slight accelerando in the chromatic melody played by the violin, almost like trying to gain momentum for the temporal transition, where it will modulate to a key of a perfect fifth above (Figure 4). We may speculate if this modulation was chosen by Raksin on purpose, but it is interesting to note that we travel five years to the past. Simultaneously, the orchestration becomes more present and richer. And ironically, the last word Mr. Lydecker says before we jump to the past is “future.”

Now, entering the world of Waldo’s memories, the full orchestra continues the rendition of the theme, adding a lot of new colors as the melody is being carried mostly by the strings. David Raksin, also used uncommon sound editing techniques to achieve a dreamlike and unworldly sound – “certain chords have a very mysterious quality – an odd quavering quality which was done by using off-center bearings in the playback machines.” (Raksin 1974, 69) – perfect for the transition into the realm of memories, adding a dreamy effect. The music is no longer diegetic; it is there not only welcoming us into the imagination of a past event, but also gives the spectator clues about how the character that evokes these memories feels about Laura.

Raksin’s approach to composing this score is expressed by a single theme that keeps travelling between diegetic and non-diegetic, changing in texture, color and key to serve the film’s narrative. Laura’s theme appears frequently throughout the picture which contributes to an “obsessive atmosphere built up around the film’s heroine” (Brown 1994, 86). It has a chromatic melody moving on top of a typical jazz harmony that never resolves, keeping a constant downward motion that never settles, creating a mood of mystery and obsession that goes hand in hand with romance and desire.

Sunset Boulevard (1950)

One might call Franz Waxman’s Sunset Boulevard score a sonata in noir. (Staggs 2002, 141)

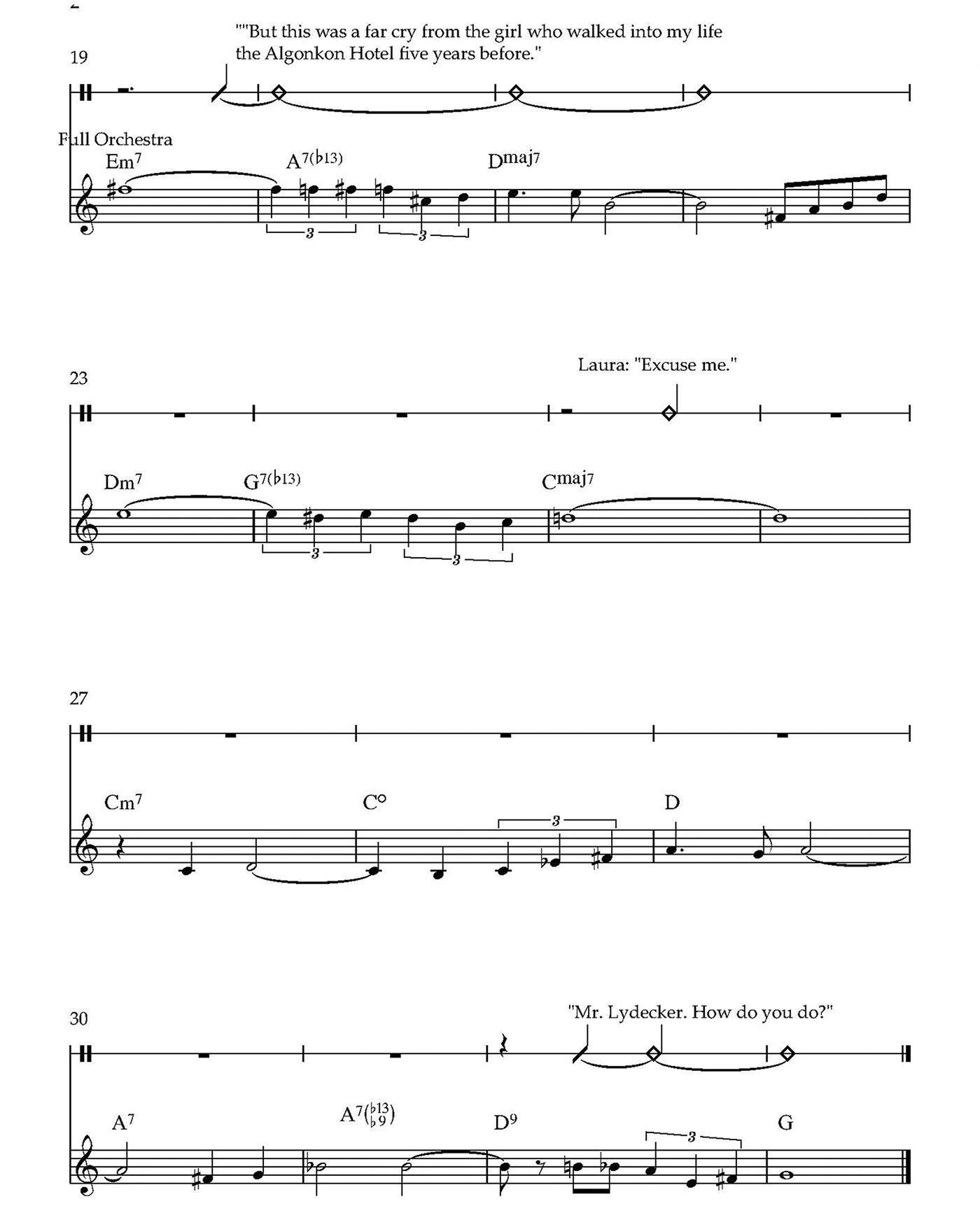

The opening credits scene of Sunset Boulevard sets the tone for the rollercoaster of events that follow, establishing a world of unpredictability, obsession, and danger. We may argue that the primary force in creating this mood is Franz Waxman’s score, with its driving rhythms, dynamic energy, insistent irregular patterns, and sharp contrasts. As the credits end, the “Stravinskyian throbs and thrusts” (Staggs 2002, 141), which characterize Waxman’s score, are joined by police sirens sounds, the narrators voice and images of police cars speeding through roads ornamented with tall palm trees.

The narrator tells us that this scene is taking place in Sunset Boulevard, Los Angeles, and that “a murder has been reported from one of those great big houses in the 10 000 block”. Soon, we see the body of a man floating in the swimming pool of a mansion, surrounded by policemen and reporters. The man has been shot.

The narrator captures audience’s attention with the following words: “Maybe you’d like to hear the facts. The whole truth. If so, you came to the wright party.” Immediately after, the music changes completely, and the audience is no longer observing from afar. They are invited to come closer and learn the truth, to become intimate with the facts. The big orchestra gives place to a single note (c#4), most likely played on a theater or Hammond-style organ. The way it is played for this purpose, and the soundwave it creates, showcases almost no harmonics, rather a pure, almost a sine wave with ethereal and hollow timbre, and a strong wavy vibrato that creates pitch fluctuations contributing to an unstable feeling. This electronically generated tone is very distinctive from all the sounds that we’ve been listening to, its otherworldly, eerie and hypnotic quality will play a crucial role signaling the temporal transition. It makes it feel dreamlike, yet unsettling, reinforcing the idea that we are being pulled into a distorted memory.

The sustained note is joined by a low brass melody in E minor. The high strings and woodwinds answer with the same melody transposed a major sixth above harmonized in triads, mostly in the second inversion. The music appears in perfect balance with the monologue, filling its gaps and underscoring the tragic, yet humorous lines of the narrator (Figure 6, bars 1 to 8). Here, we see the floating body from the underwater perspective (Figure 5). We can see the protagonist’s face for the first time and the underwater footage transfigures the group of policemen and reporters gathered around the pool, hereby forecasting the dissolve in the image.

The temporal transition occurs in bars 8 and 9 (Figure 6), where the dissolving image and the narrator’s line – “Let’s go back about six months and find the day when it all started” – are accompanied by high-pitched trills in the strings and woodwinds. These musical gestures, often used in classic film noir to signal unease and suspense, create a sense of instability and anticipation in this moment. The rapid alternation between two notes a half-step apart produces dissonance, evoking movement and acceleration, which makes the temporal shift feel uneasy, rather than nostalgic. This flashback is not a warm recollection but a fatalistic retelling of events, drawing the protagonist, Joe Gillis into a world of decay, delusion, and obsession.

The flashback takes us to a street in the middle of the city surrounded by buildings and palm trees. Two major shifts happen as the camera travels to the window of one of the apartments. Firstly, the narrator who has been talking in the third person, suddenly changes to the first person – “I was living in an apartment house above Franklin and Ivar” – only then we learn that we have been listening to the dead man’s voice from the start. And secondly, the music changes mood dramatically. Although it stays in the same minor key as the first played low brass melody, it is now lively played in octaves with a swing feel in the medium-high register of the piano. There is not much harmonic movement, the bass line “walks” up and down on the first three pitches of the minor mode steady and repeatedly (Figure 6, bars 11 to 18). This theme reappears throughout the film in different keys and variations, cleverly manipulated by Waxman as a leitmotif for the character Joe Gillis. It is an “aimless, nonchalantly syncopated melody” (Palmer 1990, 105) primarily played on the piano expressing “not just exuberance or heroism, but also downright destitution and mediocrity” (Lawson & MacDonald 2018, 266).

Notably, before the temporal transition into the past – when Joe is already dead – his theme is fragmented (Figure 6, dotted circles), played at a very slow tempo, in two different tonalities simultaneously, and spread across a large register. This reflects the disjointed nature of memory, Joe’s death, and his role as a narrator caught between past and present, reality and illusion. After the transition, however, the theme appears in its complete form (Figure 6, full circles), played at a faster tempo with more pronounced syncopation, symbolizing Joe’s youth and vitality.

Coda

The soundscape analysis of these three short film fragments, representing the first flashbacks in each of the above mentioned films, is able to provide a lot of detailed information regarding how composition (i.e. fast repetitive melody in minor mode – Double Indemnity), orchestration choices (i.e. high register trills – Sunset Boulevard), and creative manipulation of musical diegesis (i.e. Laura’s theme obsessively moving between the diegetic and the non-diegetic worlds), voice-over narrator, visual elements and both sound and image editing techniques can affect and transport the viewer through the flashbacks. For this analysis I was taking into consideration the concept of the integrated soundtrack (Kulezić-Wilson 2020; Motazedian 2024) which tends to eliminate the hierarchy between the original score, dialogue and sound effects by looking at them as a whole.

However, although the soundtrack elements were observed as a whole, the analysis evolved around the short fragments of flashbacks. It should be noted that it left out the macro dimension of the same themes and their variations, and the role they play in different parts of the films in question. Specifically, in Laura, with its monothematic approach, the composer “strongly contributes to the obsessive atmosphere built up around the film’s heroin, Laura Hunt.” (Brown 1994, 86). And in Double Indemnity, where the analyzed cue – The Conspiracy – which underscores the first flashback, is also used frequently throughout the film to “highlight the presence of the narrative Neff is creating, along with the transitions between sequences” (Brown 1994, 125).

We may ask if there is a model for a musical gesture that sustains the flashback in film noir? In Sunset Boulevard, the trills on the upper register during the dissolve in the image, can be interpreted as a blur in the audio, mimicking the visuals with the shimmering and quivering quality of the musical gesture. In Laura, the music becomes non-diegetic, modulates to a different key and a small restaurant combo suddenly turns into a big and colorful orchestra. In Double Indemnity, the music doesn’t seem to be affected by the temporal transition but certainly anticipates it.

These three flashbacks apparently don’t have a musical gesture in common, rather, they are left to composer’s imagination and creativity. However, careful balance and constant communication between the music and the voice-over of the narrator are noted throughout the chosen films. It’s noticeable how the composer was reacting to the cinematic text and its meaning, responding to it by emphasizing some words and filling the gaps by adding more layers of meaning. The intertwined narrator’s voice and music thus help producing the “real” effect of the temporal transition. Finally, in order to assess these approaches to these films’ aural elements and their scores by Miklós Rózsa, David Raksin and Franz Waxman respectively, in Doble Indemnity, Laura and Sunset Boulevard respectively, we may observe the following schematization (Table 1). It offers a brief overview of important interconnected elements such as the timing of the scene, or the cue, place and space, temporal transition, visual description, and the sound, considering both the dialogue and the music.

Finally, the transcriptions made for this article were inspired by the concept of integrated soundtrack which intends to analyze the totality of the sound elements present in a specific scene and hence highlights the necessary fusion and balance of different sound elements in order to aid the storytelling and add different layers of mening.

However, this analysis leaves space to be further deepened by enlarging its scope, encompassing not only the other scenes within the three analyzed films, and the eventual differences between the chosen flashbacks and their scores as a whole, but also looking at other important titles from the film noir corpus, to understand the novelty and particularity in sonic approaches in this cinematic genre.

Notes

1For a detailed description and systematization of different instrumentation techniques, genre and style that will be mentioned throughout the paper, see Table 2.

Bibliography

Brown, Royal S. 1994. Overtones and Undertones: Reading Film Music. University of California Press.

Kirgo, Julie. 2013. Laura. Liner Notes. Kritzerland. http://www.kritzerland.com/KL_Laura_Notes.pdf.

Schickel, Richard. 1992. Double Indemnity. BFI Publishing.

Saggs, Sam. 2003. Close-Up on Sunset Boulevard: Billy Wilder, Norma Desmond, and the Dark Hollywood Dream. Macmillan.

Turim, Maureen. 1989. Flashbacks in Film: Memory & History. Routledge.

Kulezić-Wilson, Danijela. 2020. Sound Design is the New Score: Theory, Aesthics, and Erotics of the Integrated Soundtrack. Oxford University Press.

Lawson, Matt and Laurence MacDonald. 2018. 100 Greatest Film Scores. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Motazedian, Táhirih. 2024. “Tonal Analysis of Integrated Soundtrack: Music Sound and Dialogue in Baby Driver.” In Film Music Analysis: Studying the Score, edited by Frank Lehman. Routledge.

Ness, Richard R. 2008. “A Lotta Night Music: The Sound of Film Noir.” Cinema Journal 47 (2): 52–73. https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2008.0011.

Raksin, David. 1974. “Raksin on Film Music.” Journal of the University Film Association 26 (4): 68-70.

Rózsa, Miklós. 1984. Double Life. Tunbridge Wells.

Schickel, Richard. 1992. Double Indemnity. BFI Publishing.

Saggs, Sam 2002. Close Up on Sunset Boulevard: Billy Wilder, Norma Desmond, and the Dark Hollywood Dream. St. Martins Griffin.

Turim, M. (1989). Flashbacks in Film: Memory & History. Routledge.

Filmography

Double Indemnity. 1944. By Otto Preminger. United States of Ameria: 20th Century Studios.

Laura. 1944. By Billy Wilder. United States of America. Paramount Pictures.

Sunset Boulevard. 1950. By Billy Wilder. United States of America. Paramount Pictures.

| Double Indemnity (1944) | Laura (1944) | Sunset Boulevard (1950) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cue start | 00:07:15 | 00:15:45 | 00:02:43 | |||||

| Place | From an insurance company office (indoors) to a Californian hill next to a big mansion (outdoors). | Same restaurant (indoors). | From a big mansion’s swimming pool (underwater) to an urban area of Los Angeles (outdoors). | |||||

| Temporal transition (TT) | From July 16th to the end of May in the same year. | From the main timeline to five years before. | From the morning after the murder to “about six months” before. | |||||

| Visual description | Walter Neff is in his boss’s office, recording a murder confession into a dictaphone. The scene happening in this temporal line crossfades to a past one. We are transported to Californian hill watching a car arriving at a big mansion. | Mcpherson and Lydecker are seated in a restaurant, the image dissolves while the camera does a close-up on Lydecker changing to his past memory in the same restaurant. We can now see Laura for the first time, with her back turned to us getting up from a restaurant table. | A corpse is floating on a pool, we see it from below as if we were underwater. Above the water level we see several policemen next to the pool edge and a reporter taking photographs. The image starts blurring and getting out of focus, the temporal jump takes us also to a different place, a street in the middle of a city with palm trees on both sides of the road. Camera travels to the left and we enter Joe’s apartment through its window. | |||||

| Sound | Dialogues | Character’s voice becomes narrator’s voice | Character’s voice becomes narrator’s voice | Narrator’s voice | ||||

| Music | Repetitive, lightly textured strings create a dreamlike, fatalistic mood. No ambient sounds enhance the surreal transition. The “Conspiracy Theme” recurs, reinforcing shifts between narration and action. | Lush orchestral theme with chromatic melody and unresolved jazz harmonies. Sound editing techniques create a dreamlike, obsessive atmosphere. The music moves from diegetic to non-diegetic, reflecting Waldo’s idealized memory. | Fragmented, slow Joe’s theme before transition symbolizes death and fractured memory. High-pitched trills mark the shift. After transition, the theme becomes complete, faster, and syncopated, reflecting Joe’s past vitality. | |||||

| BTT | ATT | BTT | ATT | BTT | ATT | |||

| Diegetic | X | |||||||

| Non-diegetic | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Director | Billy Wilder | Otto Preminger | Billy Wilder | |||||

| Composer | Miklós Rózsa | David Raksin | Franz Waxman | |||||

| Double Indemnity (1944) | Laura (1944) | Sunset Boulevard (1950) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instrumentation |

Woodwinds Brass Percussion Keyboard & Harp Strings |

Woodwinds Brass Percussion Keyboard & Harp Strings |

Woodwinds Brass Percussion Strings |

| Genre | Neo-Romantic, Modernistic Elements. | Classically arranged 1940s pop, Jazz and Tango Influences. | Neo-Romantic, Expressionist Elements. |

| Style | Repetitive, lightly textured string motif; static tonal center; unresolved phrases reinforcing fatalism. | Lush orchestration; chromatic melody over jazz harmonies; seamless diegetic/non-diegetic transitions; obsessive, dreamlike quality. | Fragmented leitmotif; sharp contrasts in tempo and register; trills and dissonances heightening surrealism. |