Abstract

The purpose of this study is to explore the magical nature of things, to investigate nonhuman entities, and to study from the philosophy of Object-Oriented Ontology. Rethinking Paul Wells’ scripted artefact based on the ontography concept of Alien Phenomenology, specifically for the transition of objects from real world objects to cinematic objects, Animators go through the found or made object and object as narrative stages. To explore the potential of things, we engage creators in co-speculation through Evocative Object Cards activity that evokes experience. By thinking about the theme of the secret life of things and experimenting with writing from thing’s perspective, we can realize the emotive narrative of things. Using the concept of “human-object” experience entanglement, this study conducted an experimental animation writing workshop to stimulate the tactile memory of the creators, so that they can understand how objects reveal their unique agency in the animation, and then understand the satisfaction of the participants through semi-structured qualitative interviews. The research results show that this activity has a positive impact on the creators’ creative writing of animation scripts, which not only puts forward alternative views beyond the mainstream animation stories, but also enriches the audience’s viewing experience.

Keywords: Alien Phenomenology, Thing’s Perspective, Emotive Narrative, Tactile Memory, Animation Script Writing.

1. Introduction

Experimental animation is often described with terms such as “non-objective,” “non-narrative,” “non-linear,” “non-normative,” and “unconventional” (Harris, Husbands, & Taberham, 2019, p. 1). To allow for a wide range of aesthetic, conceptual approaches, styles, techniques, materials, and media, it avoids restrictive definitions (ibid.). This study aims to further expand the imagination of animation creators by reflecting on the idea that objects may have a subjective consciousness different from human subjective thinking, or objects may have their own emotions, desires, joys, and sorrows, exploring evocative objects and the secret life of things through experimental creative thinking.

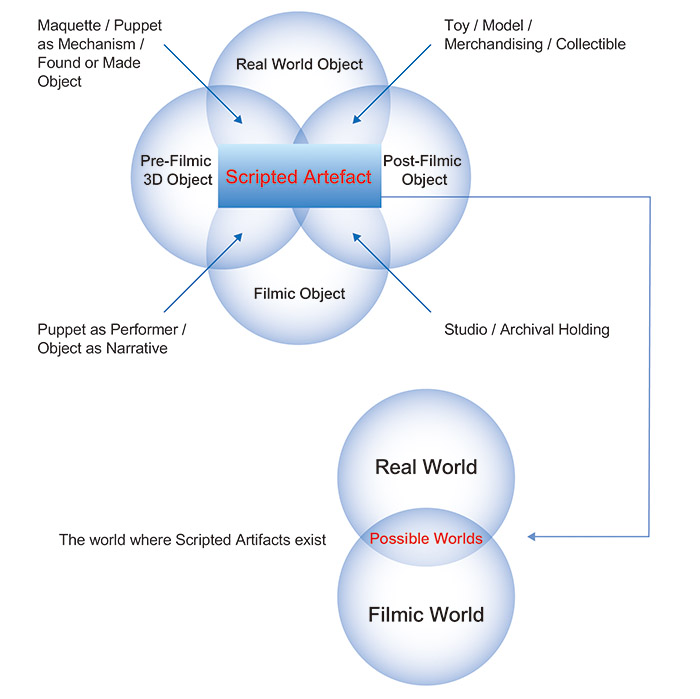

Simultaneously, this research is grounded in Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO) as its ontological foundation, drawing on contemporary speculative philosophy and related object-oriented philosophies as epistemology to explore creative methods in animation. It seeks to propose innovative perspectives in animation research by attempting to reverse traditional film theories centered on human subjects and emphasizing the significance of the material potential of things in animation creation. Animation theorist Paul Wells (2014, p.7) argues that scripted artefacts emphasize tactile memory and emotive narrative. Wells (ibid., pp.10-11) further points out the existence of scripted artefacts in different stages during the stop-motion production process, including “pre-filmic 3D objects,” “filmic objects,” “post-filmic objects,” and “real-world objects,” implying the potential for different agencies in scripted artefacts.

This paper poses the following research questions regarding the concept of scripted artefacts: 1. How can creators develop a specific emotional connection to objects as a speculative imagination of the inner life of non-human entities? 2. How can researchers apply Object-Oriented Ontology to enable creators to concretely apply these emotionally evocative experiences to the animation creation process? The following will further outline the relevant theoretical foundations and explain the exploration of these research questions.

2. Literature Review

This article conducts a literature review from two perspectives: (1) research on the Object-Oriented Philosophy, encompassing Object-Oriented Ontology and Alien Phenomenology, to acknowledge the subjective value of objects and to rethink them through new ontological and epistemological considerations. (2) A discourse on the issues of object and materiality in animation.

2.1 Research on the Object-Oriented Philosophy

2.1.1 Object-Oriented Ontology

Harman (1999, 2002) introduced Object-Oriented Philosophy (OOP), providing an alternative perspective on Heidegger’s tool analysis. It suggests that while objects serve as tools for humans to accomplish tasks, their withdrawal highlights an unknown, private inner depth beyond their functional aspect. Harman (2013, p. 7; pp. 126-127) indicates that the reality of things possesses inexhaustibility. This philosophical shift, known as the speculative turn, significantly influences contemporary art and design thinking. It subsequently developed into the widely cited Object-Oriented Ontology. As one of the pioneers of this theory, Harman (2005) asserts the following points:

- Each object has unique innate potential, supporting flat ontology— the equality of all things without privilege.

- Humans are no longer the center of philosophical thinking. Although things appear in relational contexts, humans cannot fully understand them. Therefore, one should accept the withdrawal nature of things.

- Emphasizing the importance of imagination, it encourages speculative approaches beyond empirical scientific thinking to depict the existence and interactive relationships of things.

2.1.2 Alien Phenomenology

Game designer and theorist Ian Bogost (2012a, p. 29) proposed Alien Phenomenology as a pragmatic form of Speculative Realism. This theory emphasizes the need for humans to investigate other entities in life to define the distinction between us and objects. Faced with the withdrawal nature of everyday objects as posited by Object-Oriented Ontology, Bogost (2012a, 2012b) suggests adopting an alien perspective to gain new insights into the world. This involves intentionally creating a sense of alienation and unfamiliarity to embrace unusual creative perspectives and speculate on the perceptual experiences and aesthetic judgments of objects. Bogost argues that “Make things for understanding things, not just for human use.” (Bogost, 2012b). Alien Phenomenology comprises four fundamental concepts (Bogost, 2012a):

- Ontography : Revealing the diversity and inner density of the existence of things. It involves recording basic information, purposes, and events related to things through “list” methods, indicating the internal interactions of things.

- Metaphorism : Humans can approach the inner experiences of things through speculative imagination using metaphors and analogies, achieving partial cognitive understanding even if full objectivity is impossible.

- Carpentry : A form of do philosophy, an operational practice. It is akin to a philosophical laboratory that can create a production mechanism to replicate how others experience the world. This aids in exploring the unknown and understanding the operational logic of how things construct the world.

- Wonder : Wonder is an attitude towards alien things, fostering respect for all others. It involves suspending trust in self-logic, valuing the need to evoke curiosity, create intriguing dramatic tension, and spark unexpected imagination in design.

2.2 Issues of Objects and Materiality in Animation

To delve into the discussion of objects and materiality in animation, Wells defines the objects in stop-motion animation as scripted artifacts. According to the animation production process, these scripted artifacts can be categorized into four states(Image. 1): (1) pre-filmic 3D objects, existing in the real world or created for the film, with material significance in the development of the film text; (2) filmic objects, playing roles both literally and symbolically within the film’s text or narrative; (3) post-filmic objects, often treated as work files and saved for management purposes; (4) real world objects, transformable into toys, models, commodities, or collectibles, and potentially recyclable materials (Wells, 2014, p. 10). This classification underscores that animated objects undergo different material states and meanings throughout the production process. Animators should emphasize the ways object’s function, their value in different stages, and the continuity of their meanings. By acknowledging the potential life cycle of objects and their transformations, creators can emphasize the materiality and presence of objects. This study suggests that the world of scripted artifacts encompasses possible worlds, residing between the real world and the filmic world (Lee, 2022), harboring diverse potentials of objects (Image. 1).

The exploration of objects and materiality in animation brings forth several important issues that significantly impact the art form. Firstly, the incorporation of objects and materials in animated films contributes to the visual dramaturgy by endowing inanimate objects with anthropomorphic qualities, transforming them into characters within the narrative. This anthropomorphism allows for emotional resonance and symbolic associations, adding depth and complexity to the storytelling process. Furthermore, the deliberate use of objects and materials in animation provides a rich visual dramaturgy for animation screenwriters, offering a diverse range of design forms, material associations, and narrative functions. This not only enhances the aesthetic appeal of animated films but also expands the storytelling possibilities, allowing for unique and engaging narratives.

Another crucial issue pertains to the significance of animation process materials as archival objects. The materials utilized in the creation of animated films, such as puppets, maquettes, and other physical components, serve as tangible records of the animation production process. These materials hold intrinsic value as they document the technical and artistic aspects of animation, providing insights into the creative techniques, design processes, and material choices employed in the development of animated works. As archival objects, these materials offer invaluable resources for the study and preservation of animation as an art form, contributing to the understanding and continuation of animation practices.

Moreover, the concept of the scripted artefact in animation introduces a compelling issue, emphasizing the transformative nature of objects within the animated film context. The scripted artefact exists in multiple states, transitioning from a pre-filmic 3D object to a filmic object within the narrative, and eventually as a post-filmic object or a real world object, such as merchandise or collectibles. This dynamic evolution of the scripted artefact highlights the intricate relationship between the materiality of objects and their roles in storytelling, shedding light on their significance as both narrative devices and tangible artifacts with cultural and commercial implications. The issues surrounding objects and materiality in animation encompass the visual, archival, and narrative dimensions of animated filmmaking, underscoring their multifaceted impact on the art form’s aesthetics, historical documentation, and storytelling capabilities. These considerations are pivotal in understanding the intricate interplay between objects, materials, and the animated narrative, shaping the discourse and practice of animation as a dynamic and evolving creative medium.

In summary, it is evident that contemporary philosophical trends and researchers in the field of animation recognize the significance of objects. With the aim of expanding human understanding and embracing possibilities beyond human imagination, this study asserts that the philosophy of Object-Oriented Ontology and the concept of scripted artifacts can both be applied to scriptwriting and visual creation in animation.

3. Research methods and implementation

3.1 Workshop Concepts

Sociologist Sherry Turkle (2007, p. 9) believes that Objects are able to catalyze self-creation. Certain objects in life evoke rich memories and emotions. Drawing from Wells’ concept of scripted artifacts, encompassing the found or made object stage and the object as narrative stage, this study explores how to release the material potential in animation, opening various imaginative considerations within the possible worlds of objects. In the scripted artefact context, the specifics are detailed as follows:

1. Found or Made Object Stage

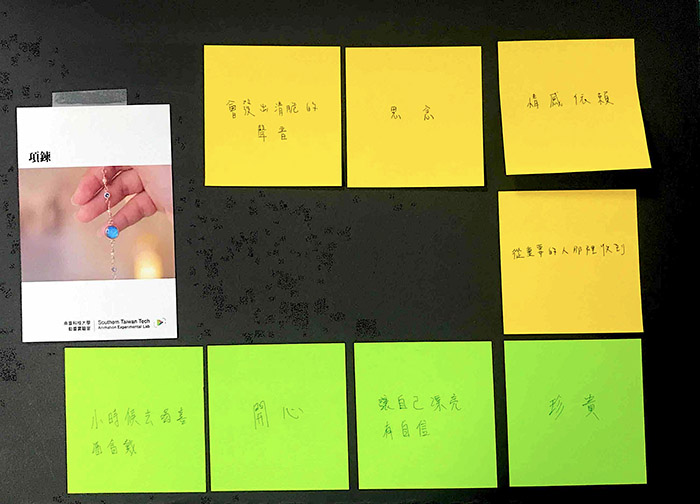

Between “real world objects” and “pre-filmic objects,” the researcher pre-collects various objects capable of evoking human memories, crafting them into Evocative Object Cards, as shown in (Image. 2).

Firstly, group participants select object cards with emotional connections, associating different creators’ memories of everyday objects. Using sticky notes within the group, they engage in co-speculation, annotating and brainstorming keywords associated with different objects (Image. 3). Subsequently, individuals share unique experience stories about their chosen evocative objects within the group.

Finally, participants compare keywords with individual stories, selecting an interesting evocative object as the group’s thematic item, then summarizing and organizing textual interpretations belonging to the object.

2. Object as Narrative Stage

Between “pre-filmic objects” and “filmic objects,” in this stage, groups can conceptualize the selected object with the theme the secret life of things. Contextualizing the object in terms of time, space, location, social relationships, etc., participants imagine the subjective perspective of the object, its subjective experiences, memories belonging to the object, and the object’s desires for the future. Groups create interactive scenario pictures depicting the object’s interaction with people, develop thing’s perspective narrative writing, and extend these concepts into the production of animated storyboards, giving shape to the animation story concept.

3.2 Workshop Implementation

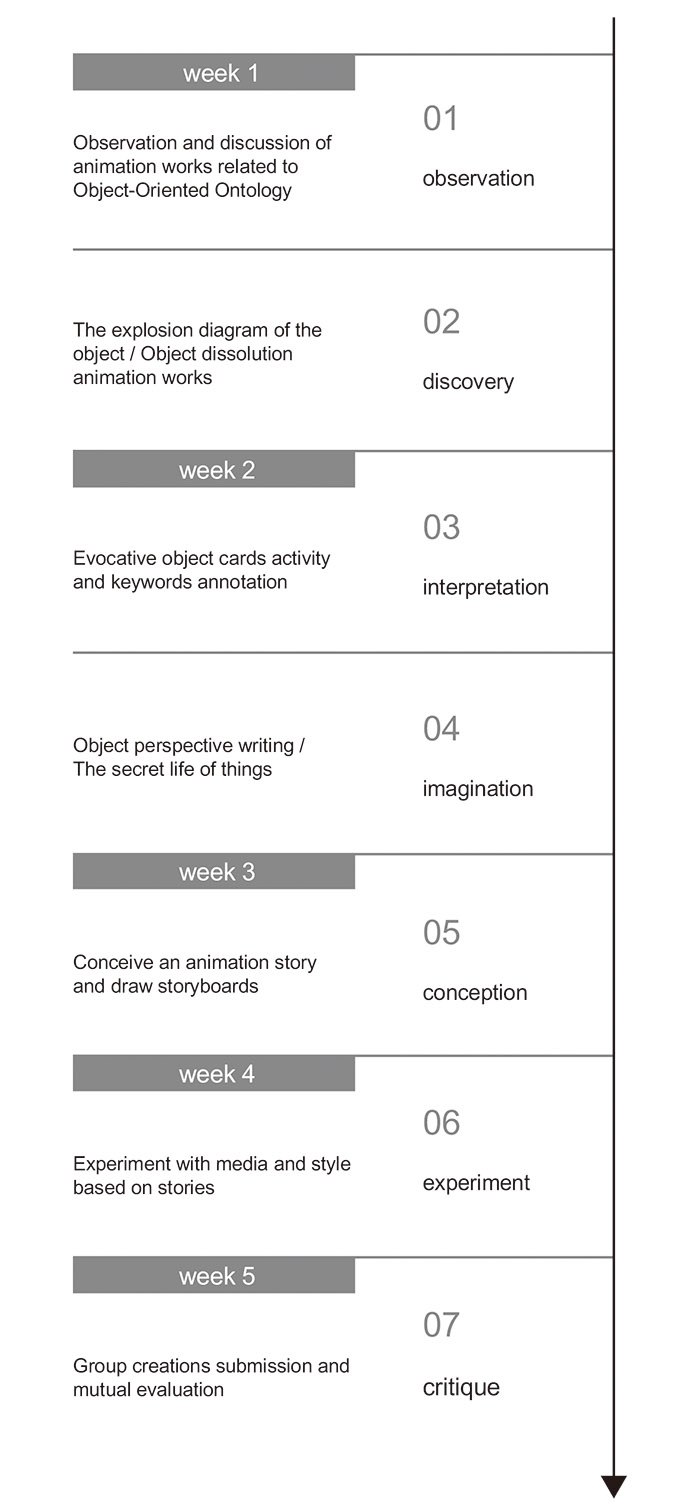

This workshop is targeted at second-year students majoring in animation from the design department of a technological university. The participants are in the age range of 20-21 years old, with a total of 8 students, comprising 2 males and 6 females. The workshop is structured into four groups, with each group consisting of two students. The entire workshop spans five weeks, with each session lasting three hours. The content is designed about a thing perspective (Giaccardi, Speed, Cila, & Caldwell, 2016), utilizing a combination of creative appreciation and practical exercises with interaction.

The workshop integrates the guidance provided in a handbook developed by this research. The sessions include instructional explanations during the creative appreciation activities, and relevant learning materials from the handbook are used to guide thinking processes. The students’ experiential process is divided into seven stages: “observation, discovery, interpretation, imagination, conception, experiment, and critique,” as shown in (Image. 4).

Detailed descriptions of workshop activities for each stage are as follows:

1. Observation

Engaging students in the observation and collective discussion of animation works that focus on a thing perspective, providing guidance to facilitate their exploration of this thematic approach.

2. Discovery

Participants observe everyday objects closely, drawing an explosion diagram of the object. Groups brainstorm how to use stop-motion techniques to disassemble, animate, and reassemble various objects, shooting an animation themed Dissolution of Things to showcase the fun of animation.

3. Interpretation

Using Evocative Object Cards, group members brainstorm emotional keywords related to each other’s chosen objects. Individuals share experience stories about their selected evocative object. Groups choose a thematic object, compare its experience story with the keywords, and generate related textual interpretations for the object.

4. Imagination

Participants engage to imagine the secret life of the thematic object, delving into intricate details of its subjective experiences in quotidian affairs. This involves articulating the object’s nuanced preferences, desires, and emotional responses in daily life.

5. Conception

Groups collaboratively conceptualize an animation narrative intricately woven around the thematic object. Employing their imaginative prowess, they delineate the storyline’s contours and subsequently translate these conceptualizations into tangible storyboards, outlining the visual and narrative progression. This process involves a fusion of creative ideation, visual representation, and narrative structuring.

6. Experiment

Groups delve into diverse materials and artistic styles intricately tied to the thematic content of their animation narratives. This stage involves hands-on exploration and creative process, pushing the boundaries of conventional approaches to uncover novel expressions. The participants need to refine their technical skills, test innovative methods, and infuse unique artistic elements into their projects.

7. Critique

Through group presentations and peer reviews, students engage in self-reflection during feedback reception, fostering self-assessment. When providing feedback to peers, students enhance their verbal expression skills and develop independent critical thinking abilities.

4. Research results and discussion

4.1 Main Outcomes of the Workshop

The workshop process combines two aspects: Creative Appreciation and Practical Exercises, using an interactive approach for the observation of thing’s perspective works and animation practices. It is divided into three main themes:

1. Dissolution of Things:

Aligning with Ontography of the Alien Phenomenology, drawing inspiration from NHK’s Japanese program “Design あ.” Students create explosion diagrams of objects based on personal observations. Engaging in group impromptu creations inspired by the concept of the dissolution of things, emphasizing the design aesthetics of presenting the overall and unit relationships of objects using stop-motion animation.

2. Writing from a Thing Perspective:

Observing works like Pixar’s animation The Blue Umbrella (2013). Students rewrite the textual script of their animation work using a first-thing perspective. Speculating on the personality, preferences, and subjective thoughts of an object enriches its worldview. It also allows creators to practice empathy with things.

3. The Secret Life of Things:

Observing animations by artists like Jan Švankmajer (Meat Love, 1989), Paul Bush (Furniture Poetry, 1999), and Adam Pesapane (PES) (KaBoom! 2004, The Deep, 2010). Inspiring students to expand their imagination on the theme of the secret life of things. Conducting group storyboard drawing and experimenting with materials and styles.

4.2 Workshop Feedback

Most students showed positive interest in the theme of the secret life of things, expressing that this unit facilitated imagination about everyday objects and contributed to creative animation storytelling. Sharing and discussing evocative objects received favorable responses. Most students appreciated how it helped establish connections with daily familiar items, aiding in creative animation scriptwriting:

“I find it interesting to think from a different perspective, using a different way to write a script. Usually, it’s from a human perspective. It’s the first time writing a script from thing’s perspective. I would anthropomorphize objects, like in Toy Story, imagining objects having emotions and their own thoughts.” (Student A)

“Thinking from a thing perspective, provides more directions for consideration. Usually, scripts are focused on a culture or a person, but this experimental animation is different, focusing on objects.” (Student B)

“Previously, stories were always thought from a human-centered perspective. Now, shifting to a thing perspective is indeed a different angle, making humans secondary, and the objects themselves become the protagonists. It’s a novel perspective.” (Student G)

“In my practice, I tried to create something out of nothing, giving characters personalities, their own desires, and goals.” (Student H)

Regarding evocative objects, the opportunity for mutual exchange of personal and others’ experiences was helpful for imagining animation stories:

“Listening to others’ different opinions about an object can help with scriptwriting.” (Student I)

“What the other person says is always something I haven’t thought of. It prevents getting stuck in one place with an object; there can be different logical thinking and different directions.” (Student A)

“Because everyone looks at things from different angles, thinks different things, and then exchanging with them gives a feeling like, ‘Ah! I can think like this too.’ And I also like hearing about my group members past experiences.” (Student G)

Finally, concerning the idea of incorporating a thing perspective into future animation story ideation exercises, most students expressed a willingness to try this innovative approach, while a few preferred to stick to traditional writing methods:

“In the future, when writing a script, I will probably think more about objects. It might not be limited to humans. This way, there will be more directions, and I can think of more interesting scripts.” (Student C)

“Maybe it’s about the style of writing, I don’t usually think about using an object as the main character in a script. But during the ideation process, it was quite fun.” (Student J)

“Non-human things can also be used as creative material. This starting point will be different from others.” (Student D)

“For a story to be told from different characters’ perspectives, it’s considered a good story. So, if you want to tell a story from the perspective of an object or an animal, it will make the completeness of the story higher.” (Student G)

For future implementations of this workshop, further exploration and discussion will be encouraged through more in-depth observations and guidance using various works. This will allow students to observe and think from different types of works, understanding how the concept of a thing perspective thinking resonates with and connects to practical examples. This approach aims to make students’ concepts in exploration and experience clearer.

4.3 Workshop Review

The overall workshop includes the observation of theme animation works, the evocative objects card activity, relevant creative thinking on the theme, animation planning and implementation, as well as experimentation with media and styles. The workshop concludes with the theme secret life of objects as the subject of the group’s animatic storyboard. During the workshop, each group also needs to undertake practical exercises with different media, as they attempt to create experimental short videos. This could be challenging for some students as the time may be relatively tight. Additionally, a single week of the workshop sometimes involves activities like observing works, discussions, and practical shooting. For students, the shooting time during the workshop may be insufficient, and it might be necessary to complete it over two weeks. In the actual execution of the workshop, students tend to initially think in terms of personification, presenting the dynamics of objects through animated character performances. Sometimes, they lean towards realism in their performances, and initially find it challenging to break away from mainstream styles. It is suggested to expose students to a variety of animation works with different styles to further challenge different modes of expression and encourage experimentation with various types of scriptwriting.

5. Conclusions and future work

5.1 Conclusions

The interview results indicate a positive reception of the experimental animation workshop applying a thing perspective. It has been affirmed by participants and shown positive impacts on animation story writing, successfully achieving the goal of aiding creative inspiration in animation. Summarizing this research, three aspects can be highlighted:

1. Designing an Experimental Animation Workshop with a Thing Perspective:

The workshop, spanning five weeks, was designed based on the core philosophy of Object-Oriented Ontology. The process was highly experimental in nature. Core works for analysis included NHK’s “Design あ” program, Pixar animation, and animations by Jan Švankmajer, Paul Bush, and Adam Pesapane. These served as case studies for viewing and guidance, fostering a unique aesthetic experience distinct from mainstream animation narratives. Analysis and practical exercises were interwoven to allow students to actively discover issues and practically implement the concept of incorporating a thing perspective.

2. Expanding Material Memory and Imagination Through the Evocative Objects card activity:

The selection of thematic object cards during the evocative objects card activity aimed to connect participants with emotional experiences related to objects. Through collaborative brainstorming using sticky notes, different emotional keywords were generated, and participants shared experiences and ideas about objects. This activity facilitated a deeper exploration of the “human-object” relationship and expanded imaginative thoughts about things.

3. Promoting Animation Story Creativity Through a Thing Perspective Writing and The Secret Life of Things Topics:

Presenting animation stories by using a first-thing viewpoint allowed creators to shift their thinking from the mainstream human perspective to considering stories from a thing perspective. This provided a different approach to character development. The secret life of things prompted creators to imagine aspects of objects beyond their everyday functionality, revealing unknown facets. Writing exercises and discussions in this regard contributed significantly to stimulating creative storytelling.

In conclusion, the workshop design and activities effectively applied a thing perspective, fostering creativity and exploration of different dimensions of animation storytelling. The positive response from participants suggested the potential for further development and implementation of such workshops to enhance creative thinking in animation.

5.2 Future Work

The implementation of this workshop began with a thing perspective, extending into considerations and practical exercises involving the dissolution of things, a thing perspective writing, and the secret life of things. This approach allows students to gradually become familiar with Object-Oriented Ontology thinking and animation expression methods. The interactive process between the creative appreciation and practical exercises phases helps students establish conceptual foundations, master technical skills, and provides an alternative creative perspective, expanding their repertoire beyond mainstream animation.

For future improvements, particularly in imparting life to objects and showcasing different degrees of agency, the research could collect more diverse animation cases. This would enable students to delve deeper into observing varied expressions in animations, allowing them to explore different dynamic styles alongside realistic performance approaches. Additionally, in the realm of a thing perspective writing, incorporating text prompts along with AI text generation technologies like ChatGPT could stimulate and expand participants’ imagination and story writing capabilities concerning a thing perspective. Finally, the model of this themed animation workshop could be extended to semester-long courses or be implemented for the public. This would not only facilitate further quantitative validation but also allow a comparison of creative thinking and expression involving a thing perspective among creators from different professional backgrounds. Overall, these recommendations aim to enhance the workshop’s effectiveness, encouraging a more in-depth exploration of animation creativity from a thing viewpoint.

Acknowledgments

This study is grateful for the support from the Ministry of Education’s Teaching Practice Project (PHA1110216). Special thanks are extended for the collaboration of the research team members, including Hong-Xian Lee, Wei-Hsin Chen, Yi-Ting Liu, for their assistance in class recording, curriculum development, and the production of teaching materials and aids, as well as the compilation of research data. Appreciation is also expressed to the participants of this teaching practice research course and the committee members who reviewed this paper.

Bibliography

Bogost, Ian. 2012a. Alien Phenomenology, or What It’s Like to Be a Thing. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Bogost, Ian. 2012b. “The New Aesthetic Needs to Get Weirder.” [Web blog post] The Atlantic, April 13. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2012/04/the-new-aesthetic-needs-to-get-weirder/255838/. Last access on 20/06/2019.

Giaccardi, Elisa, Chris Speed, Nicola Cila, and Mark Caldwell. 2016. “Things as Co-Ethnographers: Implications of a Thing Perspective for Design and Anthropology.” In Design Anthropological Futures, edited by Rachel Charlotte Smith and Kasper Tang Vangkilde, 235-248. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Harman, Graham. 1999. Tool-Being: Elements of a Theory of Objects. Doctoral Diss., DePaul University.

Harman, Graham. 2002. Tool-Being: Heidegger and the Metaphysics of Objects. Chicago: Open Court.

Harman, Graham. 2005. Guerrilla Metaphysics: Phenomenology and the Carpentry of Things. Open Court of Carus Publishing Company.

Harman, Graham. 2013. Bells and Whistles: More Speculative Realism. Hants, UK: Zero Books.

Harman, Graham. 2018. Bells and Whistles: More Speculative Realism. Translated by Fu-Rong Huang. Chongqing: Southwest Normal University. Original work published 2013.

Harris, Malcolm, Lee Husbands, and Philip Taberham, eds. 2019. Experimental Animation: From Analogue to Digital. London: Routledge.

Lee, Wan-Chen. 2022. “Exploring Aesthetic Experience of Material Imagination from the Perspective of Metaphorism: A Case Study of Adam Pesapane’s Animation Creations.” Communication presented in the International Conference on Innovation Digital Design - the New Paradigm for the Future of IoT and Digital Media (ICIDD2022), Tainan, Taiwan, 27 May.

Ryan, Marie-Laure. 2013. “Possible Worlds.” In The Living Handbook of Narratology, edited by Peter Hühn et al., Hamburg: Hamburg University. [Web blog message] https://www.lhn.uni-hamburg.de/node/54.html. Last access on 06/03/2020.

Turkle, Sherry, ed. 2007. Evocative Objects: Things We Think With. MIT Press.

Wells, Paul. 2014. “Chairy Tales: Objects and Materiality in Animation.” In Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media – Special Edition: Animation at the Cutting Edge, edited by Laura Rascoroli and Yiman Chen, University College, Cork. Forthcoming.

Filmography

Design あ 解散 ! PV. (2013). Directed by NHK. Japan.

Furniture Poetry. (1999). Directed by Paul Bush. UK.

KaBoom! (2004). Directed by Andrea Pesapane. USA.

Meat Love. (1989). Directed by Jan Švankmajer. USA.

The Blue Umbrella. (2013). Directed by Pixar. USA.

The Deep. (2010). Directed by Andrea Pesapane. USA.