Abstract

In the realm of musical performance, the role of a pianist extends beyond the mere execution of musical scores to become a pivotal contributor to artistic expression. This study delves into the auditory and visual imagination through the perception and performance of piano works by the Chinese-French composer Qigang Chen from the early 21st century, involving the performer’s meticulous response to the nuances of musical sound as well as the interplay of visual synaesthesia.

The study also explores the inherent conveyance chain within the performance process, experimenting with multimodal forms of expression. These creative choices not only enrich the narrative of the arts but also contribute to crafting a comprehensive, immersive concert experience for the audience. The principal aim of this research is to explore the prismatic view within Qigang Chen’s piano work, offering multiple possibilities of meaning and emphasizing the crucial role of the pianist in forming and elucidating the fusion of auditory and visual senses in performative action.

By transcending traditional performance boundaries, this exploration invites the audience to witness the multimodal interactions inherent in musical performances, providing a fresh perspective on dynamic exchanges between different sensory elements and cultural influences.

Keywords: Qigang Chen’s piano work, Multimodal perception, Audiovisual performance, Sensory and cultural exchange.

Introduction

In 2008, the Chinese-French composer Qigang Chen created the piano concerto Er Huang, which was commissioned by Carnegie Hall in New York. Since childhood, Chen has absorbed Chinese cultural and traditional elements, which have become an important part of his artistic expression, especially in his own musical language. As he noted in the preface of the edition to the score of Er Huang Concerto, “these tunes were an essential part of my childhood in Beijing, and always intertwined with memories of my family and the society I lived in at the time” (Chen 2009). Chen refines and reinterprets his beloved opera melodies to develop his personal repertoire of compositional materials (Chen 2023). In his music composition, Chen often imagines the specific characters and emotional qualities of his works. For instance, in another of his works themed around Peking Opera, Die Lian Hua 蝶恋花, Chen captures the delicate and reserved characteristics of the Peking Opera Qingyi role, translating these traits into the emotions and harmonic colours of the music (Chen 2023). Reflecting on the creative process of Er Huang Concerto, Chen stated that “the connection between Er Huang and its source of inspiration, Er Huang tunes1 from the classical Peking Opera repertoire, as with other works of mine, the way I applied musical elements from Peking Opera to my own writing” (Chen 2009).

In addition to the melodic element inspired by Peking Opera, Er Huang Concerto also contains a particular form that combines two structures, namely the classical concerto form and the typical form of traditional Chinese music. Er Huang Concerto is a single-movement composition centred around Er Huang melody as its main theme. In addition to its structure, which subtly outlines the exposition, development (with techniques of theme and variations) and recapitulation of the theme, Er Huang Concerto also aligns with ancient Chinese musical traditions. The pianist Xiao Ling Shao, in her doctoral dissertation, discusses the influence of the ancient Chinese musical form in Zhu Jian-Er’s 10th Symphony, Han Tang Da Qu 汉唐大曲, which integrates song, dance and instrumental performances into a comprehensive cycle of movements structured into three parts – San X散序, Zhong Xu 中序, and Po 破 2 (Shao 2010, 336). This ancient Chinese compositional style resonates in the structural design of Er Huang Concerto, which demonstrates a fusion of traditional Chinese elements within the framework of the Western concerto form.

Aside from this three-part structure, the concept of Qi Cheng Zhuan He 起承转合 (instruction, elucidation, transition and conclusion) from dramatic Chinese literature is also evident. Curiously, this cyclical structure is similar to the cyclical form of Beethoven’s sonatas, which emphasizes the introduction and coda sections and their respective connections with thematic and development materials. Many Chinese musicians have defined this traditional Chinese music concept (Li 2003; Tang 2001).

To demonstrate this musical structure and reveal the semantics behind the work, we propose a visual framework to offer the audience insights into the musical structure and help them appreciate its meaning. We formulate the visual structure in interaction with the introduction, elucidation, transition, and conclusion of the musical thematic materials, as well as the ternary form subtly shown in the macro-level layer.

Another key aspect to consider is the composer’s choice of matrix and its variations in tonal and harmonic planning. In terms of tonal arrangement, Chen adopts a combination of tonal colours, including pentatonic, diatonic, and chromatic, highlighting the fluency between purity and the collision of harmonic and timbrical colours.

The melodic design and its combination with tonal/harmonic colours embody specific personalities and emotions that, through the construction of visual patterns and shapes, can deliver a double dimension of musical feeling to the audience. In his autobiography, Chen elucidates his sources of musical inspiration, which are deeply rooted in his memories and life experiences and intertwined with profound reflection and personal emotions (Chen 2023). His musical experience reflects a synthesis of Peking Opera’s tradition and Western compositional techniques, resulting in a distinctive melodic design. The thematic melody of Er Huang Concerto is derived from Er Huang melodies. Typically, these tunes originate from a shared melodic repertoire within Peking Opera and are adapted according to different character types during performances. Chen reinterprets this melodic matrix to suit a wide range of dramatic and musical contexts. Er Huang melody is usually characterized by its smoothness and solemnity and is mostly used to express contemplative and sorrowful moods, often to convey a character’s inner monologue or profound emotional state (Gao 2001). For instance, the ethereal quality of the pentatonic theme that appears at the beginning of the Concerto sets a nostalgic tone for the musical expression. Then, the variation of the thematic elements, combined with harmonic and rhythmic tension in the middle of the piece, symbolize emotional turbulence and mark shifts in the musical narrative. Additionally, it is worth noting that within the development section of the Concerto, a dialogue emerges between a novel melodic line played by the cello and the Er Huang theme played by the clarinet. This newly introduced melody appears to diverge from the main theme, akin to a tree sprouting new branches. The new melody creates a warm colour and sensation, echoing the composer’s own description of this Concerto, which alludes to feelings of affection and warmth (Chen 2003, 199).

Regarding the metric and rhythmic aspects, Chen proves adept at intertwining traditional Peking Opera percussion such as Banshi (metric) and Luogujing (percussion system) with contemporary Western musical concepts. This combination in Er Huang Concerto offers a greater inventive scope for visual rhythm. On the one hand, there is a diversity of musical metrics that correspond to the dramatic emotions expressed, which can be perceived through the visual rhythm of the images. These metrics are revealed in the opening movement with free tempo (Sanban), in the variations of the development section that form a sequence from slow tempo (Manban) to fast tempo (Kuaiban), and in the coda with the return of free tempo (Sanban). On the other hand, the specific rhythms also mark a dynamic highlighted in the Concerto. Examples include the Luan Tan rhythm of Peking Opera or the “rhythmic characters” rhythm of Olivier Messiaen. The former is inspired by the traditional form of Luan Tan – an extroverted musical style of Chinese drama that originated around 1600. The latter features an extended duration that represents a form of psychological time.

Therefore, through a detailed analysis of Er Huang Concerto, this artistic work will create an audiovisual document that unveils scenes, figures, and movements, allowing the audience to perceive and experience them in synchrony with the music. For this purpose, we will review the theoretical aspects of the multimodal concept in performance and demonstrate the structuring of the audiovisual document linked to the musical elements described above, such as formal musical structure and visual framework, melodic design, pattern design and figures, musical timbrical/harmonic texture and visual colour/harmony, musical time/rhythm and visual tempo/rhythm.

Multimodal Concept in Musical Experience

Musical experience can be seen from a multimodal perspective, communicating through elements such as rhythm, melody and harmony, and interacting with other modes of expression, such as lyrics, images and colour to convey meaning. As Lorin Lachs explains, it is natural for people to perceive audiovisual phenomena in a multimodal way because the public experiences events as a combination of sensations, and multimodal phenomena involve stimuli that generate multiple sensory modalities almost simultaneously (Lachs 2021). Gunther Kress argues that multimodality offers a range of mode choices depending on the media involved and requires careful selection and arrangement within multimodal combinations (Kress 2009). The musician can construct a perception of the world by integrating visual and auditory information, which is particularly evident in the performing arts. Nicholas Cook presents a cross-modal relational analysis based on correspondences between media, emphasizing the role of music in the construction of audiovisual meaning. Cook argues that new meanings are created when different media layers work in concert, resulting in emergent meaning (Cook 1998):

….. both music and pictures can be understood in terms of distributional analysis, and the relationship between them can be understood as an interplay of structurally congruent media: this more or less amounts to saying that the pictures can be analysed musically. (Cook 1998, 159)

Andrew Knight-Hill (2020) further elaborates on spatiality and experience in audiovisual art by proposing a reconceptualization of the sound–image relationship as a complementary dimension that unifies audiovisual space.

The defining features of multimodal performances are their immediacy and interactivity. Rosemary Klich and Edward Scheer (2012) stress this in their book Multimedia Performance, noting that the live experience is shaped by the real-time interaction of different elements. Constantin Basica (2021) also highlights that, although performances can be analysed from the perspectives of music, theatre, and performing arts, immediacy is essential for audiovisual works. The vividness of multimedia or audiovisual performances is particularly intriguing as it involves long-term technologies associated with recording and reproduction. This viewpoint suggests that one of the key values of multimedia performance is found in the complexity and richness of live interactions among various elements.

Audiovisual Imagery in Music Performance

This study focuses on elucidating the relationship between auditory and visual imagery from the perspective of the performer. A musical work’s colours, harmonies, rhythms, melodies, textures and structure are translated into visual material through synaesthesia and multisensory imagery, which is then communicated to the audience through multimodal performances.

Numerous examples demonstrate the synaesthesia of auditory and visual sensitivities and their interaction in creations. Composers such as Alexander Scriabin included clavier à lumières (keyboard of light) in his symphonic work Prometheus: The Poem of Fire to combine music with visuals (Peacock 1985). Similarly, Painters such as Wassily Kandinsky attempted to translate musical rhythms, forms and textures into his paintings. He believed that colours resonate with each other, creating visual chords that affect the soul (Brougher et al. 2005). The pianist Håkon Austbø created a visual part for Messiaen’s piano cycle Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus, presenting and visualizing Messiaen’s colours and sounds to the audience in the live performance (Austbø 2015). These examples show the long history of efforts to combine musical and visual elements to create multisensory experiences.

In contemporary creative endeavours, the utilization of video as a medium enables the attainment of audiovisual synchronization at the production level. Michel Chion (1994) introduced the concept of added value audiovisual illusion, asserting that the amalgamation of sound and image yields more potent and expressive effects than those presented individually. When sound and image are experienced holistically, they collectively engender a novel, cohesive audiovisual domain, augmenting the overall sensory encounter. Holly Rogers (2013) further explains this phenomenon by stating that video gives artists a platform for experimentation that is unencumbered by traditional artistic conventions, allowing them to repair visual material by combining and juxtaposing images from different sources. This combination of audio and visual not only expands the artist’s creative means but also provides the viewer with a richer and more multilayered sensory experience.

Experimental Research and Technical Modals

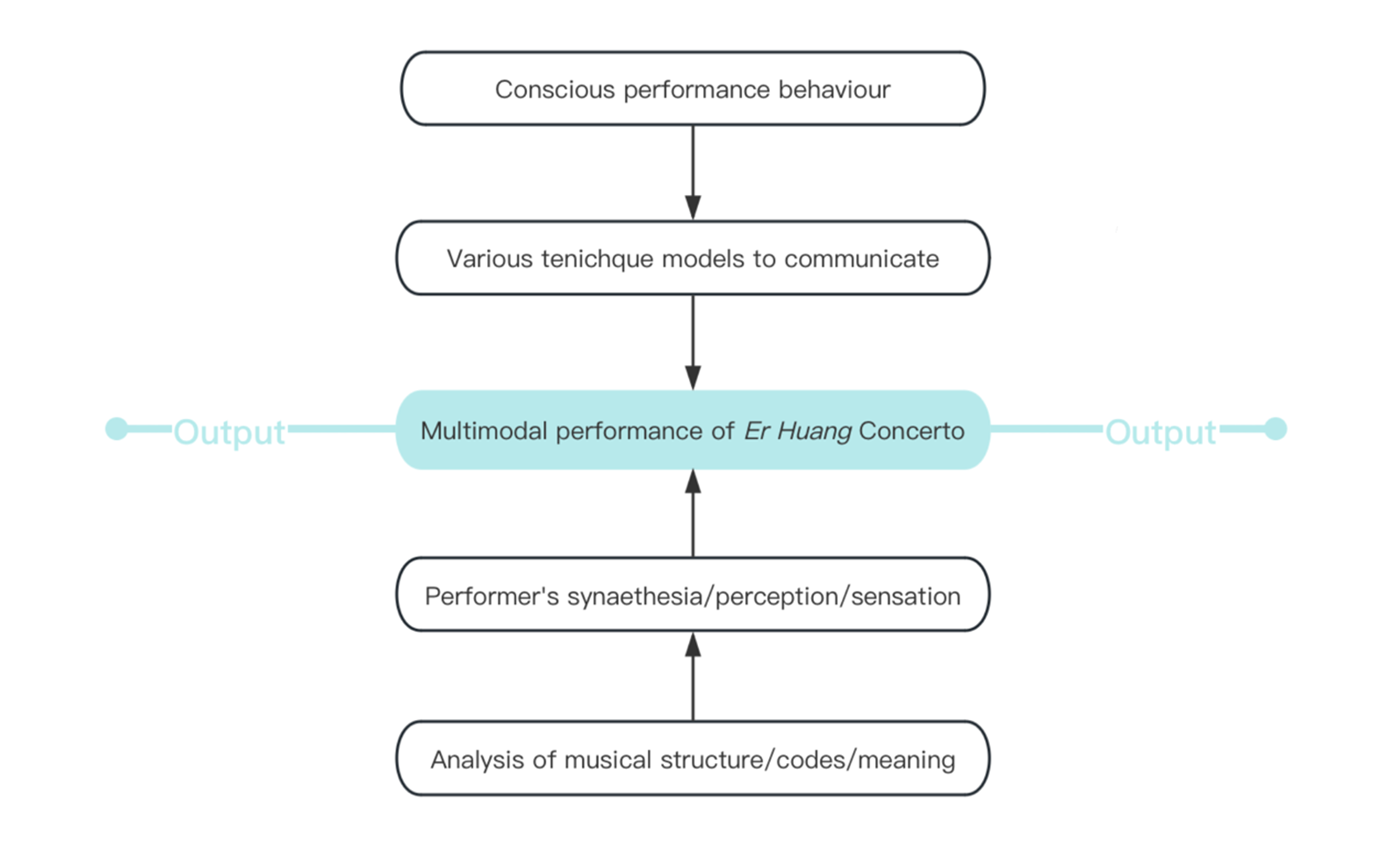

The diagram below depicts this experimental research process, starting with an in-depth analysis of the musical structure, codes and meanings of Er Huang Concerto to establish foundational insights. Subsequently, the performer’s synaesthesia and perception are examined to understand their impact on musical and artistic interpretation. The research prioritizes thoughtful analytic and artistic decisions to maintain alignment with the music’s original intent. Insights from these phases are then incorporated into multimodal performances, aiming to provide a comprehensive and immersive experience for the audience. Various technical modes will be explored and experimented with to effectively communicate the musical intent and artistic expression of the piece.

In the experimental process of creating video materials, an innovative approach is involved. Initially, an in-depth study and analysis of the musical score is carried out to understand its structure, rhythm and colour and uncover the composer’s intentions. This analytical basis allows for the identification of visual elements that closely align with the music, including visual images, motif designs and colour schemes. Based on the performer’s personal experience and synesthetic perception, the video content contains a reflection of musical sensations and stylistic qualities. The integration of advanced AI tools, specifically QiyuAI and Dreamina, plays a crucial role in this creative endeavour. Under personal guidance and model training, QiyuAI generates still images that help determine desired scenes and visual patterns. Subsequently, Dreamina enables the transformation of static images into dynamic visual materials, ensuring that the visual elements evolve in harmony with the rhythm and timbral and dynamic colours of the music. This process requires meticulous editing to synchronize the visual materials with the music, representing a significant challenge and requiring ingenuity in audiovisual production. Navigating the complexities and potentialities of the relationship between algorithmic processes and artistic intent requires iterative experimentation and model refinement to align the outcome with the performer’s perception and creative vision. The visual outcome redefines the creative path while preserving the performer’s artistic intent and interpretative stance. This dual role – musical interpreter and visual creator – enriches the performer’s imagination as well as the sensitivity of the auditory image. In terms of output, it improves the performance experience by integrating video elements, thus contributing to a more immersive and collaborative presentation. This approach also opens new avenues for artistic exploration with a multimodal perspective, combining traditional practices with contemporary technological advances.

Audiovisual Document Editing with Music Synchronization

The defined visual framework corresponds to the musical structure of Er Huang Concerto mentioned above. The introduction and the coda sections are linked with nostalgic feelings, which are reflected in Video I through the presence and absence of the female Qingyi青衣 character in Peking Opera. While the elucidation (exposition) part presents the entire theme of the Concerto, its hybrid characteristic is conveyed in Video II through the combination of two painted faces, Qingyi and Hualian, transitioning from serenity to tension. To emphasize the main musical characteristics of the transition (development) section, another three videos are edited with distinctive meter, rhythm and expression. Video III displays a slow tempo to explore the state of contemplation and thinking. This state begins to flow in Video IV, moving with spinning ripples and running water. The tempo accelerations and changes in feeling reach a climax in Video V, which reveals agitation and accumulated force.

Video I:

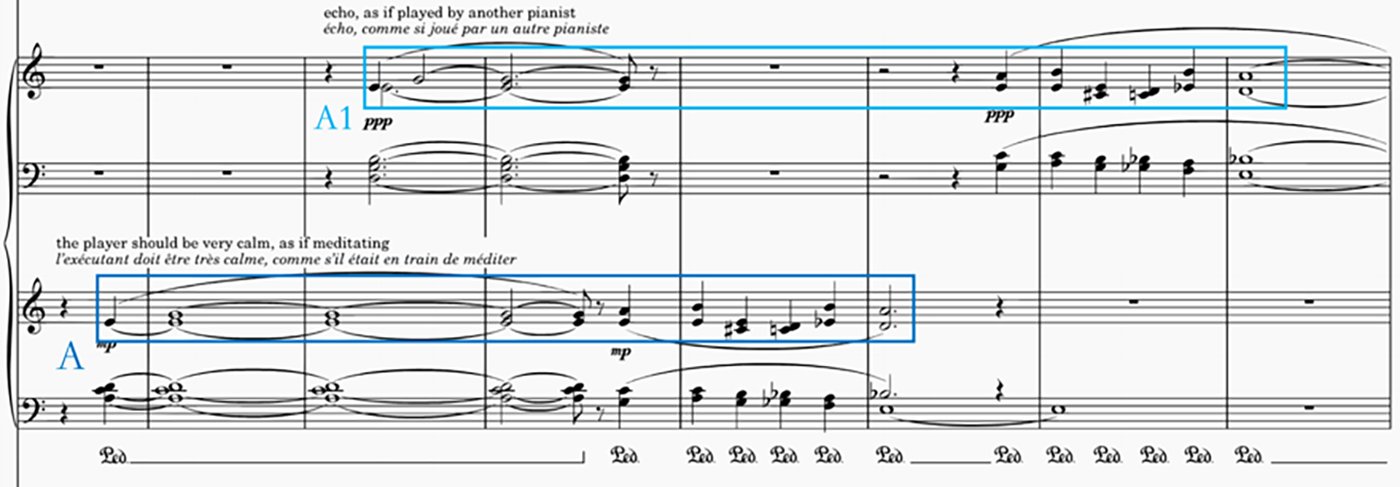

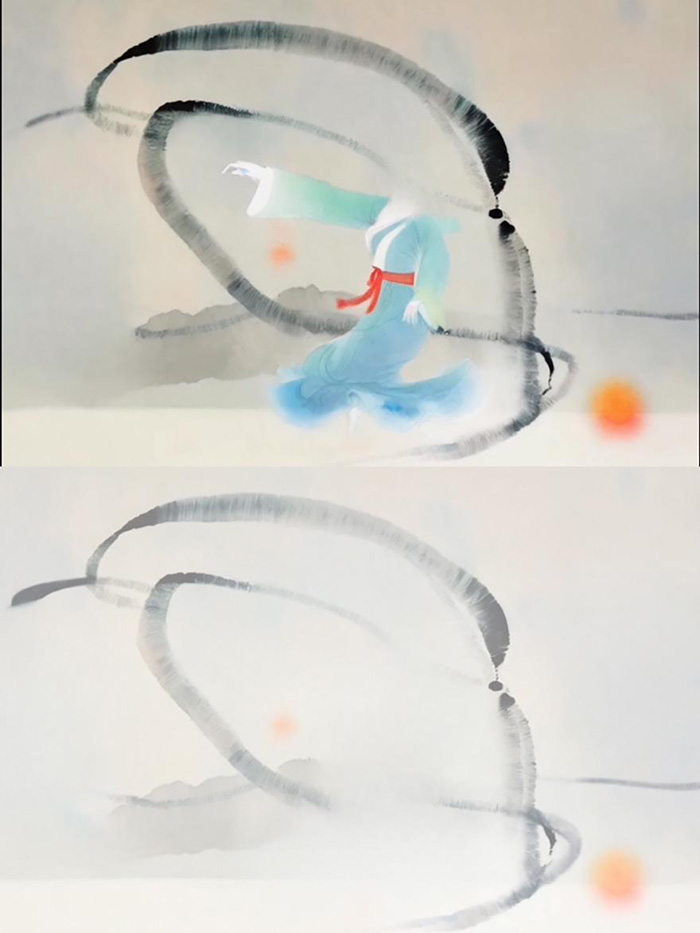

The Concerto begins with an introduction that highlights two characteristics. On the one hand, a temporal distance between present and past is depicted through the sound and echo effect of the broken theme, which is inspired by the Er Huang melody of Peking Opera. On the other hand, Chen combines the pentatonic, diatonic and chromatic modes to create a hybrid theme, thus offering several possibilities for changes in harmonic colours. This generates sensations between meditative melancholy, tension and brightness. In the first six measures of the introduction section (Example 1), the motif from the theme is expressed using pentachords, creating a pure and ethereal auditory effect. A dialogue unfolds between two musical layers, the first (A) sounds calm and melancholic, and the second (A1) generates a subtle meditation under the effect of echo.

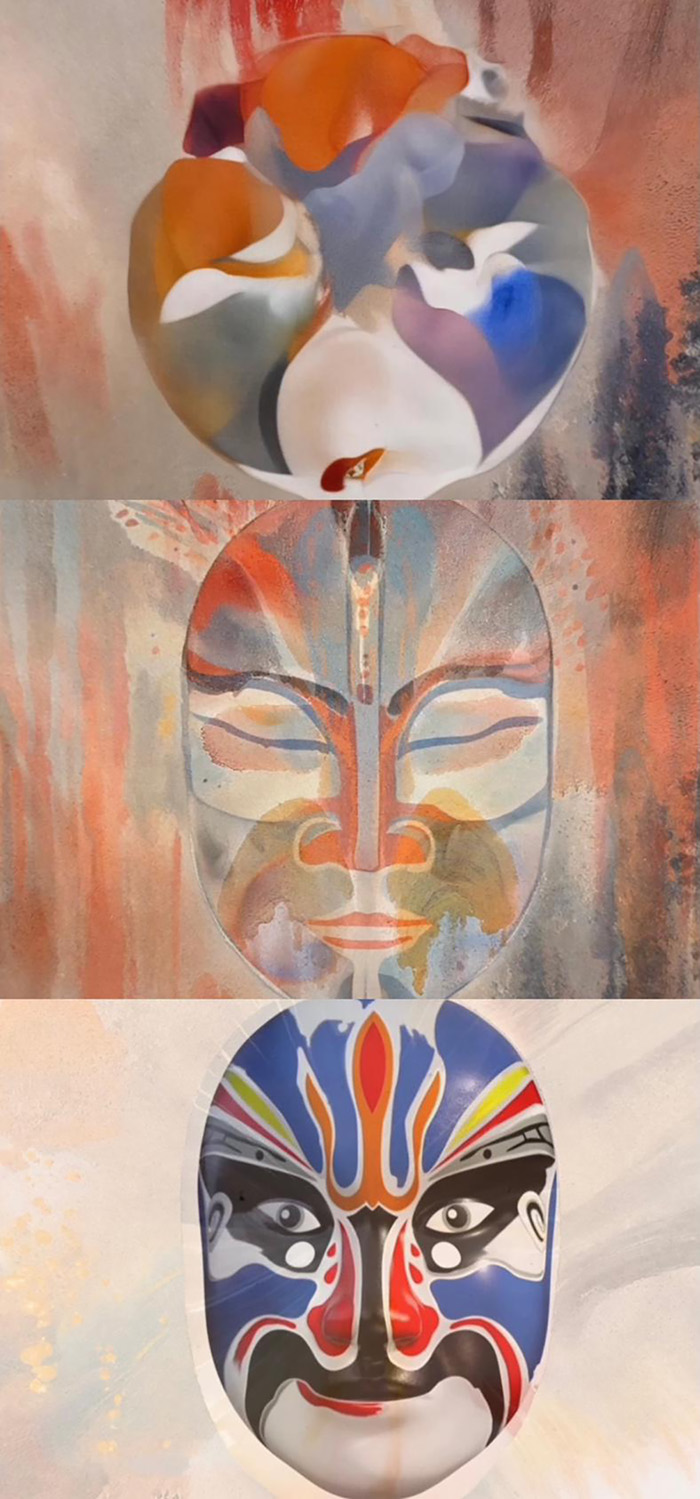

To complement this effect, the visual imagery begins with the figure of the Peking Opera female character, Qingyi, whose soft colour tones align with the contemplative nature of the introduction. As the theme has not yet fully emerged, the Qingyi character’s facial details are intentionally blurred to convey an abstract quality, as shown in Image 1. The black ink lines in the image represent the abstract form of the water sleeves, a common costume prop for Qingyi characters. As the music transitions to the echo section, the video retains the same background but conceals the figure of the Qingyi character, leaving only the lines of the water sleeves to create the impression of an echo, highlighting the qualities of recollection.

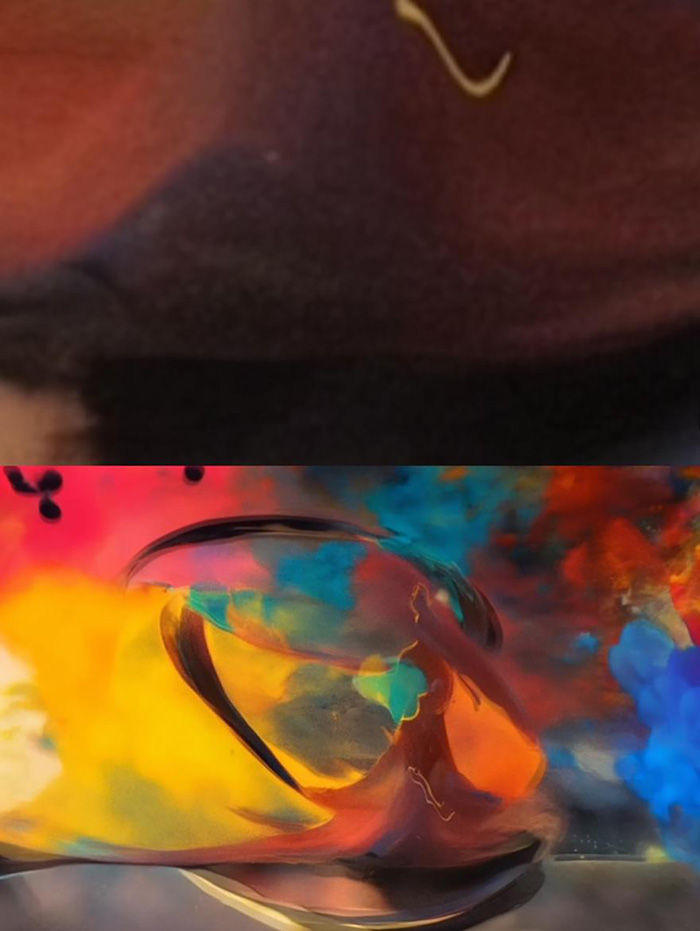

From measure 21 onwards, the chords are juxtaposed into tense heptachords with the augmented fourth interval within, and as the harmonic complexity increases to cluster-like, the texture becomes thicker and more aurally intense. This transition in the music effectively prepares the escalation of visual dynamics and the degree of saturation and warmth of the colours.

To reflect the transition from the soft and simple pentatonic scales to the rich chromaticism and dynamic intensity of the sections, bright and contrasting colours were chosen for the visuals, including deep red, bright orange, intense blue and rich green, thereby visually conveying the intensification of the music.

Video II:

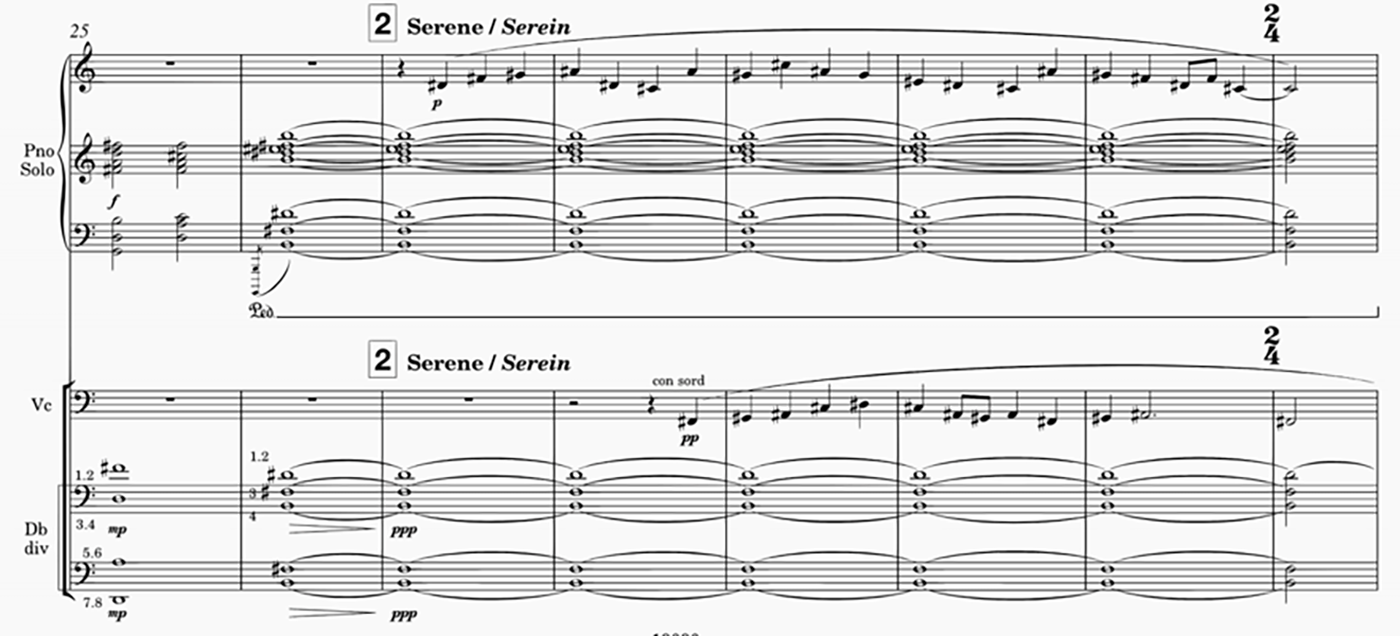

From measure 27 to measure 32, the piano part presents the complete main theme for the first time without breakdown. This theme appears in the D-sharp Zhi pentatonic mode, which gives the music an atmosphere of purity and serenity. This is clearly demonstrated by the music term Serene in Example 3.

Thus, when editing the video images, a soft and refined portrait of the Qingyi character’s painted face was utilized, due both to the pertinence of the theme’s integrity and the emphasis on the emotion (serenity) behind the music.

From measure 33 to measure 39, the progression of overlapping chords quickly transitions the serene atmosphere of the music to one of greater tension. The string sections, in coordination with the piano, feature a layered cluster of eleven notes. This tense and dissonant sound significantly alters the final purity of the theme, introducing a more intense auditory image.

The gradual intensification of visual elements aligns with the musical dynamic and timbrical palette. As depicted in Image 4, the painted face of the gentle Qingyi character transitions to the painted face of Hualian, which is masked with bright colours and angular lines.

Video III:

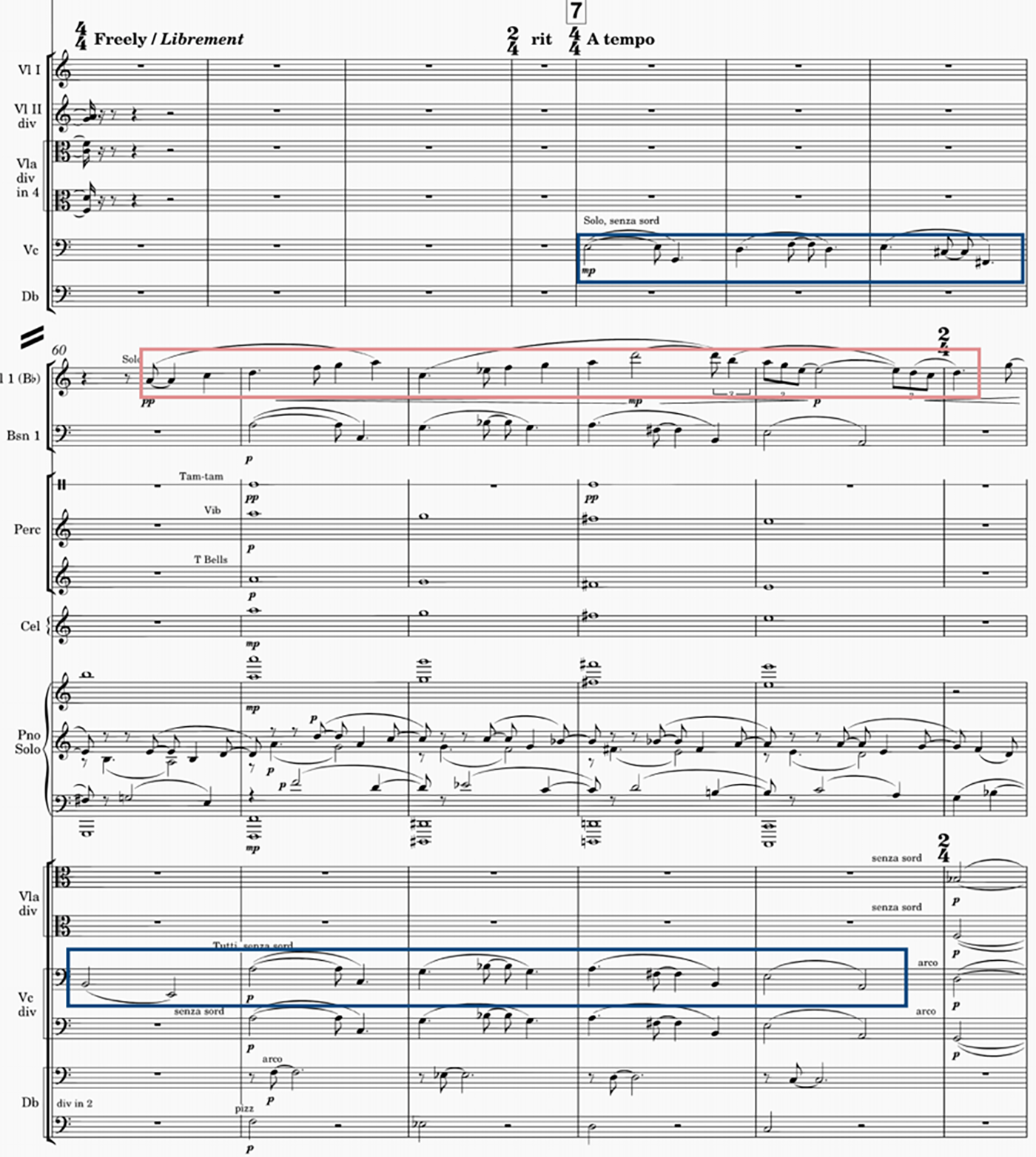

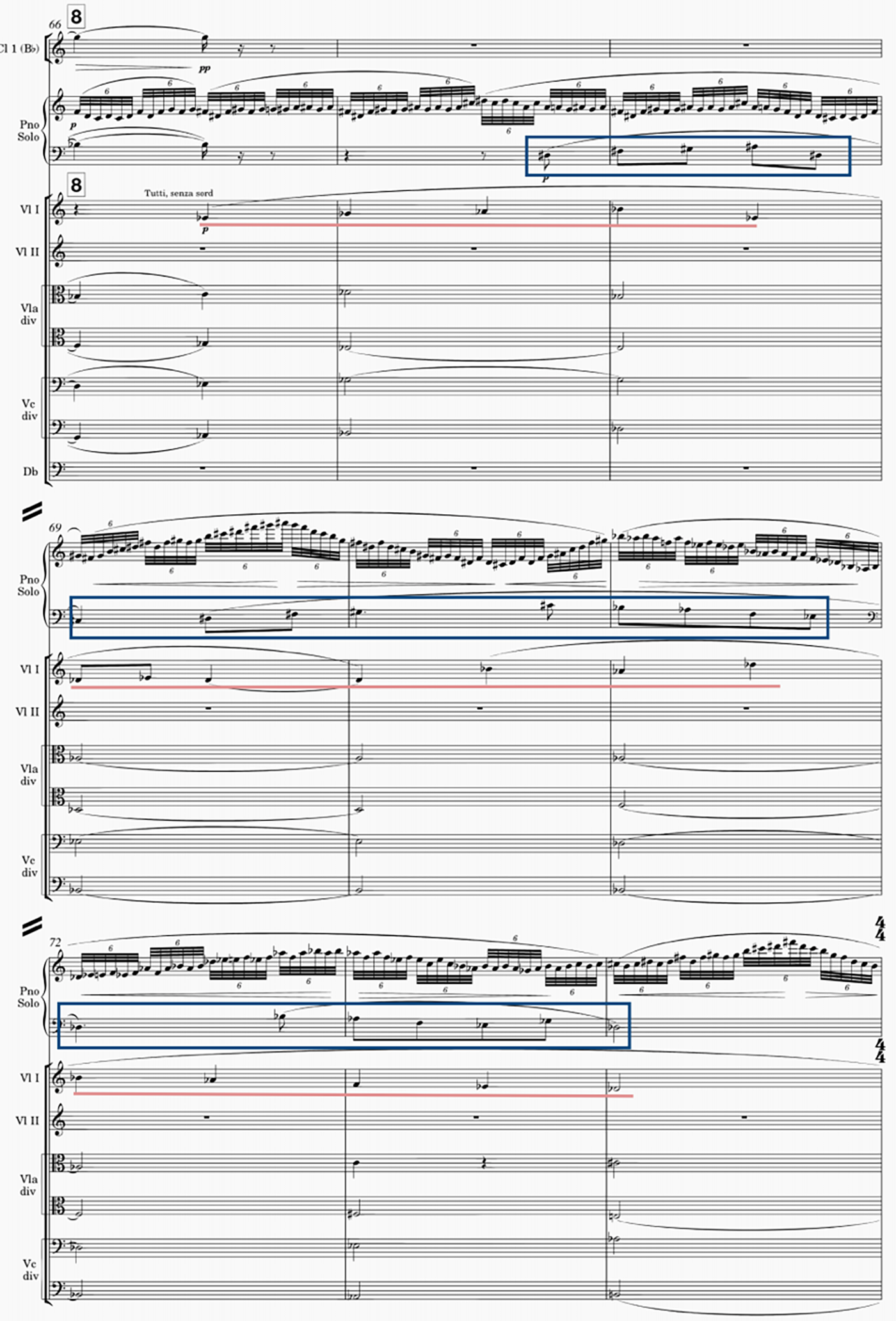

In this first variation of the transition (development) section of the Concerto, new melodic material appears in the cello line (as illustrated by the part circled in blue in Example 5), together with the harmonic texture of the piano, creating the tonal colour of the mixolydian mode (Greek mode). This new auditory sensation creates a contemplative lyricism, with an inner spiritual depth. The cello’s melodic line unfolds gradually and dialogues with the main theme played in the clarinet voice (circled in red in Example 5), symbolising a thought seeking a flowering of life. As the music progresses, it evokes a gentle yet deeply expressive feeling.

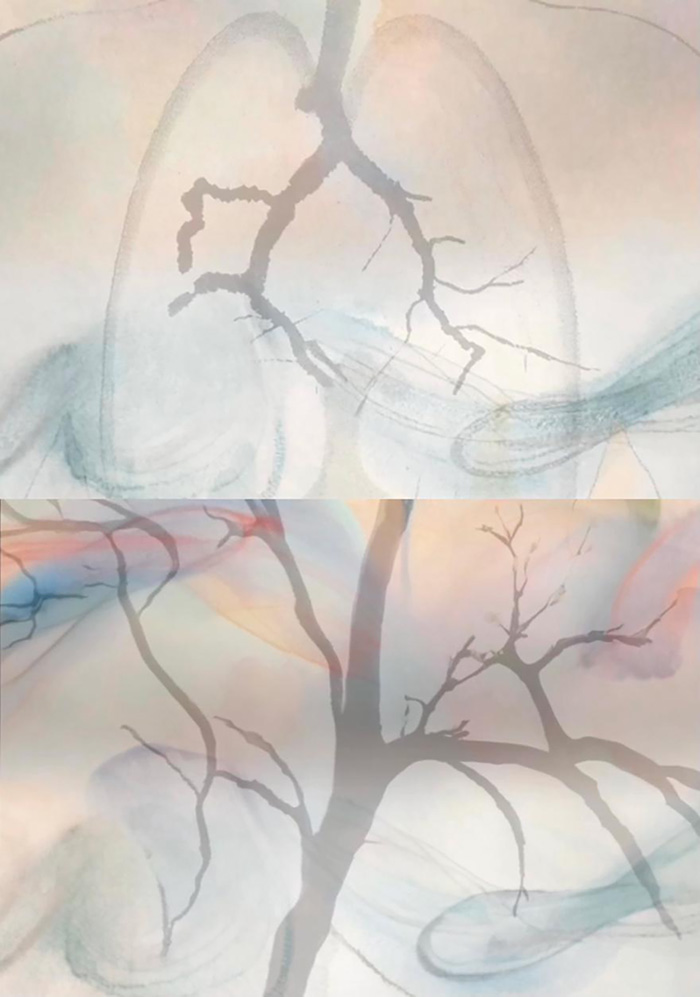

To complement this contemplative sensation, the accompanying video imagery portrays the palpitations of blood vessel branches slowly emanating from a heart, synchronized with the rhythm of the melody (Image 5). The gentle colour effects and pronounced branching patterns visually resonate with the unfolding and contemplative lyricism of the cello voice. Furthermore, the video introduces a dialogue between the cello and clarinet voice, depicted through the opposing flow of lines in different colours. The lower section of the image features dark-coloured lines that embody the cello’s deep timbre, while the vibrant hues of the upper lines reflect the clarinet’s rich and expressive tonality. The branching of the blood vessels becomes increasingly distinct against a backdrop of soft, flowing colours, enhancing the visual narrative and its alignment with the musical dialogue.

Video IV:

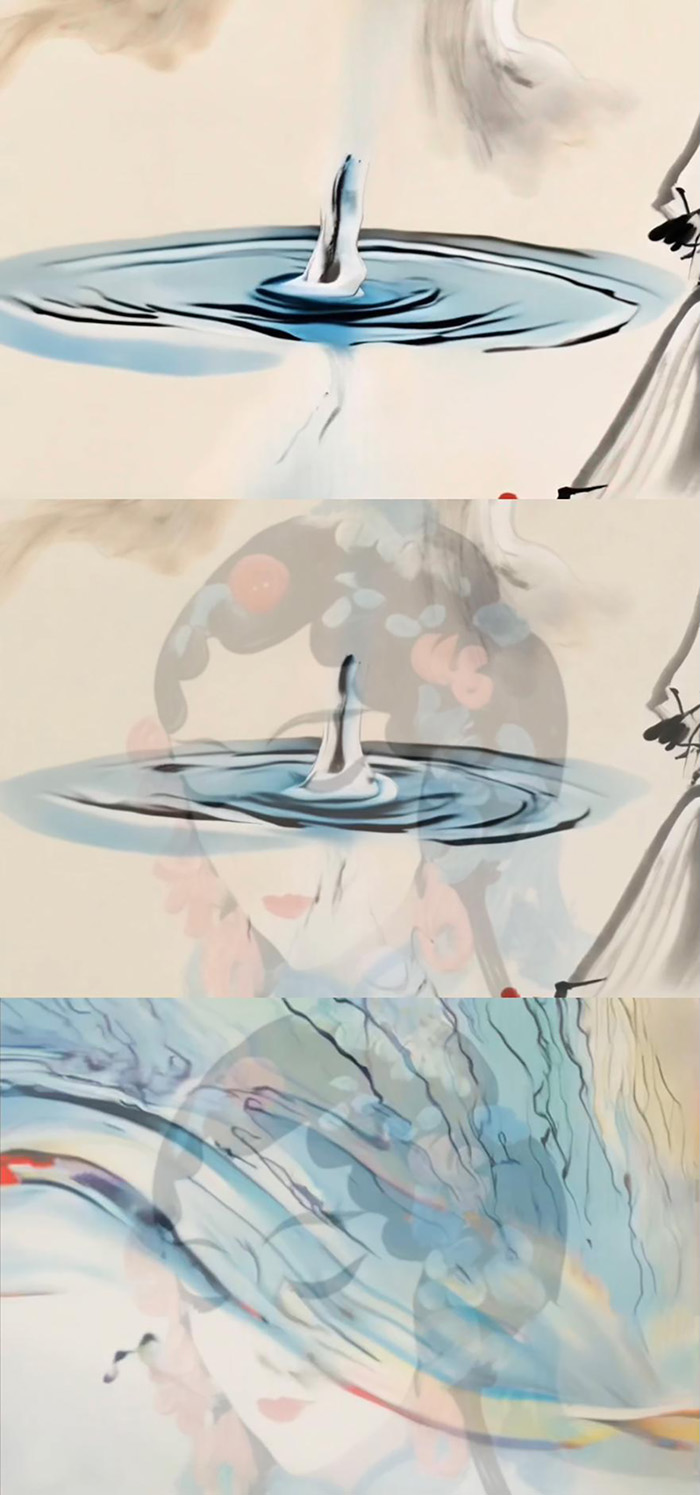

In the second variation of the transition section, the melodic shape becomes broader. The lyrical quality of the main theme appears in the first violin at measure 66 (highlighted in red in Example 6) and in the piano at measure 67 (highlighted in blue in Example 6). Notably, from measure 71, the key changes from sharp to flat due to the use of the mixolydian mode with the lowered seventh, which evokes a sensation of floating between the pentatonic scale and the mixolydian mode. Simultaneously, the rhythm in the piano part accelerates with thirty-second note sextuplets spread over nine measures, which is comparable to the rhythmic effect of liushui 流水 in Peking Opera. This rhythmic fluting effect also stands out through the combination of pitch sets between pentatonic and chromatic.

Considering the spiral fluidity of the initial musical texture, the initial content of the image was chosen to show the ripples of the water. However, the scene changes from measure 67. On the one hand, the fluidity of the melody increases in amplitude (covers a larger register), so that the image changes from calm ripples to the relatively intense flow of water. On the other hand, the addition of the theme melody creates a more layered video image. By superimposing thematic elements to activate the visual content, editing software was used to manipulate the image and colour harmonies to ensure that the image of Qingyi character and the element of flowing water were blended into one dynamic scene, as shown in Image 6.

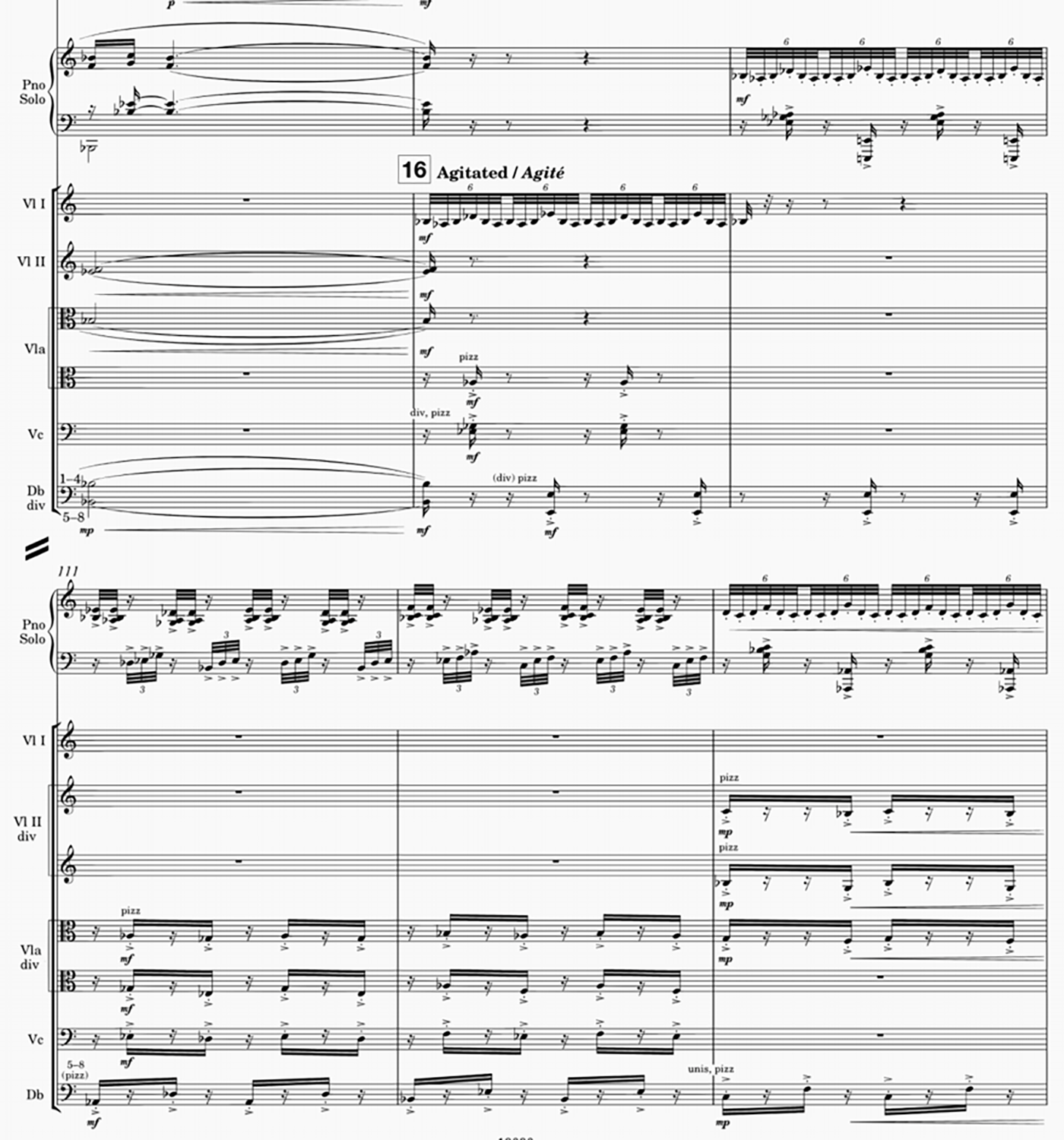

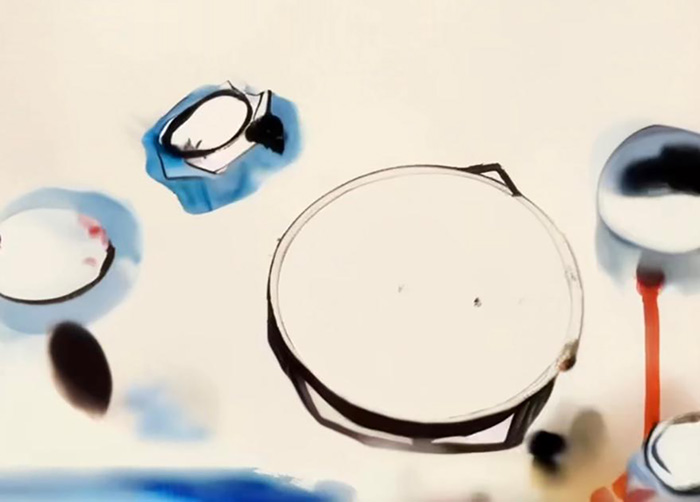

Video V:

In the third variation of the transition section, the tempo becomes more agitated and the rhythmic organization seems more irregular and ragged. At the same time, various articulations are used in both the piano and string playing to achieve shifts in timbrical colours. The first violin part in this section features dense and rapid sequences of notes, as shown in Example 7, primarily in thirty-second note sextuplets and triplets that contribute to a highly agitated atmosphere. The piano part then repeats the same melody. Meanwhile, attacks such as staccato, small accents and pizzicato, along with the staggered entries between the piano and string parts, form a pointillist effect, which creates a more scherzando and dramatic sensation.

Therefore, the corresponding visual material is closely associated with the dynamic visual elements in Peking Opera. The first image depicts a scene of Jinghu, the principal string instrument in Peking Opera, highlighting the fast bowing techniques and rapid bow changes.

To reflect the percussive qualities, Peking Opera percussion instruments, such as gongs and drums, are included in the video. The rhythms of the appearance of the gongs and drums in the video are synchronized with the pointillistic rhythms of the music and their auditory vivacity.

Additionally, to emphasize the lively dancing nature of Peking Opera, the chosen visual element include multiple overlapping, fast-moving fans, which are most-used props in Peking Opera performances. These fans are arranged in a circular motion, creating a sense of dynamism and energy. The use of blurred edges and dynamic lines enhances the perception of rapid movement, evoking a sense of excitement and fluidity.

Additional examples could be illustrated and discussed; however, due to the length of the article, we chose the five most prominent examples.

Conclusion

This study meticulously examines Qigang Chen’s Er Huang Concerto from the perspectives of audiovisual imagery and multimodal perception. The performer’s synaesthetic perception and creative decisions play a pivotal role in this process. The concerto is structured as a single movement that fuses classical concerto elements with traditional Chinese musical styles. This cohesive structure, such as instruction–elucidation–transition–conclusion, guides the visual storyboard, ensuring that the progression of musical themes corresponds to the visual transitions and narrative chain. The theme melody, based primarily on a pentatonic scale, creates a specific modal atmosphere that can be visually represented through colour schemes and corresponding images. The hybrid character of the theme, developed by diatonic and chromatic tonalities, also provides visual creation with a greater range of colours and patterns/figure designs. Harmonic progressions within the Concerto facilitate visual transitions, deepening the emotional resonance through colour changes that mirror the music’s shifts in tension and release. Furthermore, analysing metric and rhythmic patterns enable the identification of rhythms in the images that remain synchronized with the music, thus maintaining a visual consistency that complements the dynamic rhythm of the music.

In this experimental research, the multimodal performance method begins with the performer’s conscious behaviour, reflecting deliberate actions informed by an understanding of the piece. This leads to diverse technique models to effectively communicate the music’s nuances. Subsequently, the performer’s synaesthetic perception – interpreting sounds as visual and tactile sensations – deepens their engagement with the music. This perception is supported by a detailed analysis of the musical structure, codes and meanings, enhancing the performer’s interpretation. Finally, all these elements converge in the multimodal performance of the Concerto, which integrates auditory and visual expressions, enriched by continuous feedback and refinement throughout the process. In addition, by employing advanced artificial intelligence tools and video editing technologies, the research demonstrates how technological advancements can create dynamic visual materials that closely synchronize with musical elements.

The study also underscores the critical role of the performer in multimodal interactions, which is essential for defining and clarifying the fusion of auditory and visual senses. By transcending traditional performance boundaries, this research enhances our understanding of the sensory and cultural interactions that define new musical experiences. Future research will explore the dynamics between multimodal performance and audience engagement, aiming to enhance and deepen artistic expression and introduce multiple layers of meaning through this interaction.

End notes

1 Er Huang is an important singing style in Peking Opera music. Characterized by relative calmness, slowness and depth, it is ideal for expressing contemplation and sadness (Gao 2001).

2 San Xu features flexible rhythms, Zhong Xu introduces fixed time with slow, lyrical melodies transitioning into dance rhythms, and Po concludes with a fast and agitated tempo associated with a major climax.

Bibliography

Austbø, Håkon. “Visualizing Visions: The Significance of Messiaen’s Colours.” Music & Practice, Volume 2. https://www.musicandpractice.org/volume-2/visualizing-visions-the-significance-of-messiaens-colours/. Accessed May 5, 2024.

Basica, Constantin. 2021. Audiovisual Performance. Music Technology Online Repository. https://mutor-2.github.io/HistoryAndPracticeOfMultimedia/units/05/. Accessed May 25, 2024.

Brougher, Kerry, Jeremy Strick, Ari Wiseman and Judith Zilczer. Visual Music: Synaesthesia in Art and. Music Since 1900. London: Thames & Hudson.

Chen, Qigang. 2009. ER HUANG for piano & orchestra. London: Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd.

Chen, Qigang. 2023. “悲喜同源:陈其钢自述” Sorrow and Joy from the Same Source: Chen Qigang’s. Autobiography. Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company.

Chion, Michel. 1994. Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen. New York: Columbia University Press.

Cook, Nicholas. 1998. Analysing Musical Multimedia. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Gao, Xin. 2001. Introduction to Chinese Beijing opera. Qingdao: Shandong University Press.

Klich, Rosemary and Edward Scheer. 2012. Multimedia Performance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Knight-Hill, Andrew. 2020. “Audiovisual Spaces: Spatiality, Experience and Potentiality in Audiovisual. Composition.” In Sound & Image: Aesthetics and Practices, edited by Andrew Knight-Hill, 49–64. London: Routledge.

Kress, Gunther. 2010. Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. London: Routledge.

Lachs, L. 2024. Multi-modal perception. In Noba textbook series: Psychology, edited by R. Biswas-Diener. and E. Diener. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers.

Li, Jiti. 2004. “中国音乐结构分析概论” Introduction to Structural Analysis of Chinese Music. Beijing: China. Central Conservatory of Music Press.

Peacock, Kenneth. 1985. “Synesthetic perception: Alexander Scriabin’s color hearing.” In Music. Perception 2(4): 483–506.

Rogers, Holly. 2013. Sounding the Gallery: Video and the Rise of Art-Music. New York: Oxford University. Press.

Shao, Xiao Ling. 2010. Diálogo entre tradição e contemporaneidade na música erudita do século XX: a. obra sinfónica do compositor chinês Zhu Jian-ER. Doctoral Diss., University of Aveiro.

Tang, Zhechi. 2001. A Dictionary of Chinese Proverbs. Jilin: Yanbian People’s Press.