Abstract

While at first sight, there is not much in common between the genre of melodrama (or romance) and film noir, there are films that may fit into both categories. My presentation will focus on how is it even possible when, for instance, the requirements for the female characters are radically different between melodrama and nfilm noir. On one hand, we need a woman that – quite necessarily – suffers and is being manipulated by others (melodrama; as discussed, for instance by Sarah Kozloff in Overhearing Film Dialogue) while on the other we have a woman that is often a leading character and is the one that manipulates others (nfilm noir). Besides that, while melodrama is focused on romantic relationships and/or family life, it is something that is mostly missing from film noir. But still, we may argue that there are films that may be understood as “melodrama noir.” The following paper will focus mostly on two case studies: Beyond the Forest (King Vidor, 1949), and Leave Her for Heaven (John M. Stahl, 1945) that will prove different approaches to this unique mixture of two genres (provided we understand nfilm noir as a genre, that is problematic, and might be a presentation on its own).

Keywords: film noir, melodrama, hybrid genre, Leave Her to Heaven, Beyond the forest.

Introduction

Film noir, one of the most remarkable styles of the US cinema, falls usually into one of the following genres: detective film, thriller, spy, crime, or gangster film. However, there are also noir horrors, westerns, and melodramas. Several analyses of individual film noirs bordering melodrama have already been published, and this text intends to extend this list.

I will compare two film noirs with very similar plots, that are often referred to as melodramas: Beyond the Forest (BTF, King Vidor, 1949) and Leave Her to Heaven (LHTH, John M. Stahl, 1945). I am particularly interested in whether they may be understood as melodramas. To what extent do these films fit into this genre? And to what extent do they differ from it?

Melodrama as a genre is usually defined by a specific narrative, strikingly similar to films falling into this category. Therefore, I will focus as well on the narrative style of these two films and how it fits into the known definition of melodrama. However, films’ dialogues will also be of importance to me – as Sarah Kozloff argues: “melodrama has long been associated with excessive talk” (Kozloff, 2000, p. 235).

***

Traditionally, melodrama focuses on romantic or family relationships. However, the opposite is generally true of film noir: “[I]f successful romantic love leads inevitably in the direction of the stable institution of marriage, the point about film noir, by contrast, is that it is structured around the destruction or absence of romantic love and the family,” writes Sylvia Harvey (Harvey, 1989, p. 25).

What exactly is happening in those two films? In both, we follow the story of a married couple: in BTF, Rosa and Lewis Moline, and in LHTH, Ellen and Richard Harland. Both marriages are going through a crisis: Rosa plans to divorce her husband and marry her lover, a wealthy businessman from nearby Chicago. But his intentions do not match Rosa‘s, so she does not have any other option than to return to her husband. Eventually, she gets pregnant and when it seems that the marriage is saved, her lover reappears, and this time he proposes marriage to her, which causes a series of tragedies – Rosa shoots a family friend who is aware of her infidelity, then aborts her child by jumping off a cliff and dies as the consequences of the miscarriage.

Ellen and Richard’s marriage has a different dynamic: it seems idyllic at first. Ellen, however, loves Richard so much that she does not intend to share him with anyone and lets his younger brother drown under her watch. She plans to become pregnant to reattach Richard to her, but she hates the unborn child, miscarries by jumping down the stairs, and subsequently commits suicide, which she stages as a murder to be blamed on her sister Ruth, whom Ellen sees as her rival. The similar stories differ in their conclusion: while BTF captures the last shot of Lewis bending over his wife’s corpse in a bleak setting, next to the railway tracks, the final shot of LHTH shows Richard embracing Ruth, sister of the dead Ellen, against the idyllic backdrop of the lake and woods encircling Richard’s home, called Back of the Moon.

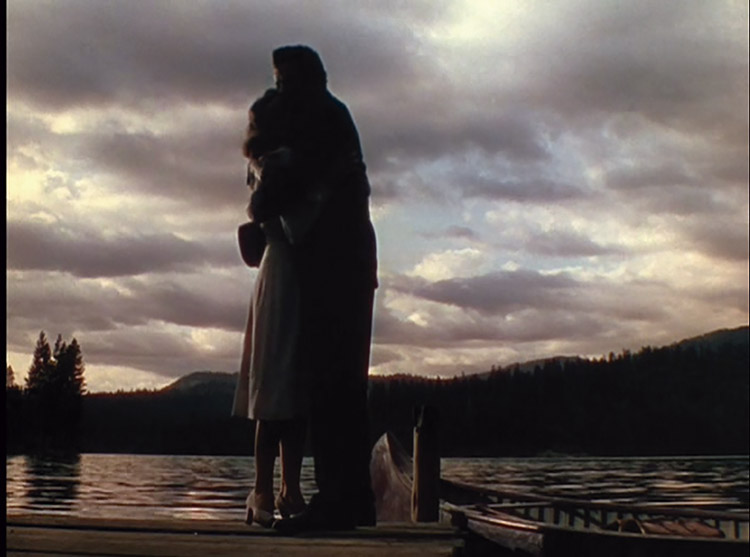

There is an apparent difference in the mood of the endings, but it is not only the content of the shot that matters, but also its composition: the final shot of BTF reminds us by its bleakness plenty of film noirs: it is a close-up of the heroine’s corpse and her husband standing helplessly over it. There are shadows present, as well as the typical chiaroscuro effect (almost half of the shot is hidden in darkness). The ending of LHTH is by no means noirish: unlike BTF, it captures the couple from a low angle, revealing a sky with a low sun and a romantic landscape in the background (the fact that LHTH is shot in Technicolor, of course, plays a role here, making it one of the few color film noir).

Here we see the first contradiction between seemingly almost identical plots – namely, whose story we are following. While the protagonist of BTF is Rose – the film ends with her death – the protagonist of LHTH seems to be rather Richard. Ellen dies 16 minutes before the end of the film, and although the following minutes are also planned by her (the trial of Ruth, accused of Ellen’s murder, takes place), she is physically absent, and the audience’s attention is thus focused on the relationship between Richard and Ruth. Moreover, we see Richard in the very first shot of the film – he approaches the pier on a boat – while Ellen does not appear until couple of minutes later, at the moment when the film’s flashback begins. The flashback is framed by the narration of Richard’s attorney, who is speaking from the position of his client rather than Ellen.

Rose’s privileged position in BTF is also confirmed at the very beginning of the film – It begins with the heterodiegetic narrator’s account of the trial of Rose Moline; in a calm, slow voice, the narrator is recounting the circumstances of the trial when suddenly Rose “bursts in” (as if from another time and space) in her strong, high-pitched voice: “Why should I kill him?” The sudden interruption of the narrator’s voice is accompanied by a distinct change in movement. In the opening three minutes of the film, multiple shots are capturing the peaceful life of the town; if there is any movement, whether it is the camera‘s movement (panning, tracking shot) or movement of something in the frame (train, smoke, children), it is movement from right to left or vice versa. However, during the narrator’s words, Rose suddenly rises from under the bottom edge of the screen, apparently getting up from her chair (however, we don’t see Rosa’s position at the beginning of the shot, we only understand it in retrospect). Her movement is therefore perpendicular to the movements we have seen so far in the film. The long shot of the courtroom audience is instantly transformed into a medium shot, and Rosa, with her movement, striking make-up, extravagant blouse, deep cleavage, and frightened, albeit determined expression, draws our attention to her. We may claim that BTF is the story of Rosa, and LHTH, as a whole, is the story of Richard. However, the flashback in LHTH is, like BTF, the story of the heroine, that is, Ellen.

Another question to ask is, whether the heroines of these two films are active or passive. When comparing melodrama with film noir, it is the different presentation of the female character that is apparent at first sight. While film noir is characterized by the femme fatale, the mysterious woman who is active, enchants the hero, and manipulates him, melodrama is mostly characterized by the passive female character who is heavily influenced by the hero and acts only as she is allowed to by him. Our sympathies are usually with the victim; in film noir, it is sometimes a man, but in melodrama, it is usually a woman. As Jonathan Norton states in his thesis on three films on the borderline between film noir and melodrama: “In the noir film, a male character is often victimized by the steely, cold-hearted femme fatale; in the family or maternal melodrama, it is often the opposite case, with the female character depicted as a self-sacrificing victim of emotionally detached family members” (Norton, 2004, p. 11). Kozloff also states that melodrama is about self-sacrifice (Kozloff, 2000, p. 237) and that women are “mistreated and silenced by patriarchal strictures” (Kozloff, 2000, p. 244). However, the heroines of the two discussed films are most certainly not abused and are the only ones who are “emotionally detached”. To achieve their goal, both murder their relatives or friends without hesitation (brother-in-law Danny in LHTH and family friend Moose in BTF). Neither Rosa nor Ellen is passive; both act actively, to the point of breaking the rules of the society in which they live. For example, they both propose marriage to their lover. Rosa clearly says: “I want you to marry me.” and Ellen even formally proposes to Richard: “Darling, will you marry me?”

The active roles of the heroines are related to their desire to achieve their goals at any cost. But what is their goal? As Thomas Elsaesser puts it, “another recurrent feature [… is] that of desire, focusing on the unobtainable object” (Elsaesser, 1994, p. 62). Indeed, the goals of both Rosa and Ellen are unattainable, albeit for different reasons: Ellen, in fact, longs for her father, Rosa for life in the city.

The incestuous nature of Ellen’s relationship with her dead father (Electra complex) is often mentioned in analyses of LHTH. Ellen’s longing for her father cannot be fulfilled – It is a social taboo. Moreover, her father is dead and Ellena is looking for a replacement. She likes Richard precisely because he resembles her father. Jonathan Norton reminds us how this desire for her father motivates all of Ellen’s actions (Norton, 2004, pp. 19-20): she murders Danny, for whom Richard functions in a role of an absent father because she feels that she is being pushed into the position of Danny’s mother, i.e. Richard’s partner, which is contrary to what she desires (him functioning as her father). For the same reason, she has to get rid of the unborn child, as Richard would become the father of a child, not of her. It is worth mentioning that the scene of the abortion is preceded by a scene in which Ellen discovers that her room which was later rebuilt into her father’s laboratory is now being rebuilt again by the members of her family into a room for the unborn child. She is very frustrated by this discovery. The place that once was her room should be a space for a child who will replace her in her relationship with Richard. Ellen clearly sees Richard as a replacement for her dead father, which may be confirmed by the fact that Ruth originally transformed her father’s laboratory into Richard’s study.

Rosa’s goal in BTF is unobtainable from the beginning of the film. Rosa longs to leave the small town where she lives, and we learn this fairly early in the film. She asks her lover to help her leave the town. When he wonders why she doesn’t leave on her own, she replies, “What as? A telephone girl? A stenographer? A waitress? You could get me out.” Just as in LHTH, it seems that Ellen would marry anyone who reminded her of her father, here it seems that Rosa is willing to marry anyone who would enable her to live in the city. She is aware that she can’t stay alone in the city, and that she needs someone to make her position easier. Rosa’s desire to leave the small town is demonstrated in her frequent walks to the train station, from where the trains to Chicago regularly leave. At the end of the film, despite her poor health (the result of a deliberately induced miscarriage), she decides to finally go to Chicago and dies near the tracks where the train to Chicago is incidentally passing right at that moment. She lives up to her words from earlier in the film: “If I don’t get out of here, I’ll die. If I don’t get out of here, I hope I die. And burn.”

* * *

Sarah Kozloff has researched the dialogue in melodramas and has defined what dialogue in melodrama looks like. To what extent does the dialogue in films we discuss here are resembling melodramatic dialogue?

Kozloff states that “Dialogue in melodramas functions to reveal feelings, and it does so through a heightened, even overblown, rhetorical style” (Kozloff, 2000, p. 239). Peter Brook, in his study of melodrama in the theater, similarly argues, “The desire to express all seems a fundamental characteristic of the melodramatic mode” (cited in Kozloff, 2000, p. 238). Indeed, in both films under study, the characters express their feelings quite openly – everything they feel, they openly state. In LHTH, Ellen clearly says what she feels. After she breaks up with her fiancé, the following conversation takes place between her and Richard:

Ellen: “Darling, will you marry me?”

Richard: “I mean, you quirky little...”

Ellen: “And I’ll never let you go. Never, never, never.”

Another time, Ellen says, “I love you so I can’t bear to share you with anybody.” Not only does Ellen express her feelings with words, but she also affirms them with her actions. Indeed, she has no intention of sharing Richard with anyone: she resents having a helper, Thorne, on the Back of the Moon estate, and when her mother and adopted sister Ruth come to visit her, she is desperately trying to make them leave as soon as possible. Her desire to have Richard all to herself culminates in letting his brother Danny drown – it is clearly a punishment for him refusing an offer to move into Ellen‘s mother’s house (that is, leaving her and Richard alone). When Richard distances himself from her after his brother’s death, she takes Ruth’s advice and becomes pregnant. However, she soon realizes that the unborn child is only another rival, therefore she decides to abort a child by jumping down the stairs. She soon notices that Richard is spending a lot of time with her sister Ruth and decides to get rid of Ruth as well. She does so unexpectedly – she poisons herself and arranges everything so it appears that it was Ruth, who has murdered her.

However, it is not only Ellen who expresses her opinions and feelings, even when other characters primarily talk again about Ellen’s feelings, instead of their own – with one notable exception – her sister Ruth, see below. Based on the dialogue we thus understand Ellen’s psychological profile long before it is fully revealed when she kills Danny. Her mother, for example, explains to Richard in the twelfth minute of the film why they decided to scatter Ellen’s father’s ashes exactly here: “It was his favorite place. He used to come here a lot with Ellen.” Her words suggest an unusually strong bond between Ellen and her father. Ellen’s affection for her father is, in fact, the driving force of the plot – Richard even bears a striking resemblance to Ellen’s father. Ellen decides that she will “never, never, never” let Richard, her father’s substitute, go.

At the nineteenth minute of the film, Richard wonders why Ellen has been out so long. Her mother tells him, “Nothing ever happens to Ellen.” This sentence also says a lot about Ellen: it implicitly depicts Ellen as an active woman, it is she who controls the course of events around her. When, at the twenty-ninth minute, Richard and family friend Glen watch a swimming race in which Ellen is participating, Glen states, “Ellen always wins.” Indeed, Ellen always wins and her first loss comes only after her death, when Rose is not accused of her murder.

In the scene preceding Danny’s murder, Ellen’s mother tells Richard: “What’s wrong with Ellen? There’s nothing wrong with Ellen. It’s just that she loves too much. Perhaps that isn’t good. It makes outsiders of everyone else. But she can’t help it. You must be patient with her. She loved her father too much.” Her speech thus becomes a foreshadowing (and indeed an explanation) of the murder that follows.

The only supporting character who talks about her feelings is Ellen‘s adopted sister Ruth. Not long before Ellen decides to commit suicide, she tells her, “I don’t envy you, Ellen. All my life I’ve tried to love you, done everything to please you. All of us have… Mother, Father, and now Richard. And what have you done? With your love, you wrecked Mother’s life. With your love, you pressed Father to death. With your love, you‘ve made a shadow of Richard. No, Ellen, I don’t envy you. I‘m sorry for you. You are the most pitiful creature I’ve ever known.” Towards the end of the film thus Ruth outspokenly sums up what has been so far delivered only in hints.

Even in BTF, the characters clearly express what they want. Rosa tells her lover that she wants him to marry her; he tells her sometime later that he intends to marry another girl; and after some time he changes his plans again, comes to a small town, and proposes to Rosa. Not only protagonists are outspoken: when Moose’s daughter comes to visit the Molines with her father, she recounts the whole family history:

Carol: “I always knew I had a real father somewhere.”

Moose: “I ran away and left her, imagine that.”

Carol: “And by the time he started to look for us again, my mother had divorced him and remarried. And now that I’ve found him, that’s all that matters.”

According to Kozloff, another essential characteristic of dialogue in melodrama is that it is “ornate, literary, charged with metaphor” (Kozloff, 2000, 239). In both films, we can find passages where the characters use metaphors. In BTF, for example, a “flowery” conversation occurs when Rosa and her husband are resting at a clearing in the woods while lumberjacks are cutting down trees around them:

Rosa: “Funny, isn’t it? All these trees standing here feeling so tall and so strong. And then someone comes along and says: it’s your turn. And they get the mark of death on them... I wonder if they know?”

Lewis: “People don’t, at least most people don’t. It’s not always death, though. Sometimes it’s a disability or an ordeal of some sort.”

Rosa: “See any mark on me?”

Lewis: “Rosa, of course not.”

Rosa: “Don’t you see it, Lewis?”

Husband: “No, why?”

Rosa: “I always thought you were a rotten doctor. I‘m going to have a baby.”

This dialogue occurs approximately at half of the film and foreshadows the further development of the plot... Rosa feels “marked” in the same way as trees that are destined to be cut down. Her “marking” (i.e. her pregnancy) is a sign of inevitable death. Lewis, without knowing what he is talking about, calls this “mark” a disability or an ordeal of some sort. And that is exactly how Rosa perceives her pregnancy. It is not surprising, therefore, that Rosa successfully attempts to miscarry her unborn child – she jumps off a cliff. Her health issues after the miscarriage then lead inevitably to her death.

We find similar “literary“ speeches in LHFH as well. Richard, for example, tells Ellen at the beginning of their relationship, that he used to go to the docks, watching the ships being loaded:

Richard: “She looked good to me and she smelled good. I didn’t know where she was going, but I knew I was going with her. And I did”

Ellen: “Why did you come for me tonight?”

Richard: “Well, I… I don’t know exactly. Everybody assured me you’d be perfectly all right. I guess it was just an impulse.”

Ellen: “Like the time you took the freighter?”

Richard: “Yes... You knew I was coming up there tonight. You were waiting for me, weren’t you?”

The comparison between Ellen and the ship (both of which attract him so much that he can’t resist) is particularly striking in this film, as the boat is here an important means of transportation. Richard’s mansion, Back of the Moon, is on a lake and is accessible only by boat. Ellen’s mother and her adopted sister Ruth arrive at the estate by boat, and at the end of the film, Richard takes the boat to meet Ruth. But above all, it is on the boat that Ellen decides to kill Danny. This scene has been seen by some as a turning point – as a break between the melodramatic and noir parts of the film (Norton, 2004, p. 20), as may be suggested by the dark sunglasses Ellen puts on at the very moment she realizes the necessity of getting rid of Danny to achieve her own goals. With a single movement, Ellen becomes a femme fatale.

According to Kozloff, “in most melodramas, the driving tension of the plot stems from one character keeping some secret, a secret that the viewer knows” (Kozloff, 2000, p. 242). Kozloff emphasizes that “in no other genre is the viewer’s superior knowledge of the narrative so influential” (Kozloff, 2000, p. 242). Indeed, in both films, we can speak of unrestricted narrative, in the sense how Bordwell and Thompson define it. The viewer knows more than any other character in the film. Only the viewer knows that Ellen lets Danny drown and that she does not fall down the stairs, but jumps on purpose. Only the viewer (and Rosa’s lover) knows that Rosa is having an extramarital affair; when her secret is revealed to Moose, only the viewer knows that Rosa shoots him on purpose. In both cases, however, all the secrets are revealed towards the end of the film. Ellen confesses to Richard both: that she killed Danny and that she deliberately induced an abortion, and Rosa confesses to Lewis that she has a lover and that she murdered Moose. In LHTH, it is only the viewer who is aware of Ellen’s precise plan to commit suicide in a way that will make Ruth look guilty of murder. Only the viewer knows that Ellen went to the basement, where her father’s lab supplies are collected, to get the poison. Ellen and her father’s fate is thus reunited, and the fact that Ellen wishes to be scattered in a place called Heaven, where the ashes of her father are also scattered, only confirms the pathological nature of their relationship, a relationship that lasts beyond the grave.

Through the prism of several texts on “pure” melodramas, we have discussed two films, understood by many as film noirs, Leave Her To Heaven and Beyond the Forest. These two films certainly fulfill some of the features of melodrama: the narrative focuses on a love relationship, the dialogues are straightforward, even when sometimes flowery, and both heroines long for an unattainable goal and have their secrets. However, the heroine does not suffer in silence (that is usually the case of melodrama‘s heroine) but acts. Of course, this difference is to be expected, given that one of the basic features of film noir is the femme fatale character. Her presence is almost a necessity for film noir. Both films are, therefore, above all, films noir. However, as can be seen, other features of these two films show a clear resemblance to “pure” melodramas. We may conclude, that both of these films can safely be called melodrama noir.

Bibliography

BORDWELL, David – STAIGER, Janet – THOMPSON, Kristin: The Classical Hollywood Cinema. Film Style & Mode of Production to 1960. New York : Columbia University Press, 1985. 513.

ELSAESSER, Thomas: Tales of Sound and Fury: Observations on the Family Melodrama. In: GLEDHILL, Christine (ed.): Home is Where the Heart is. London : BFI, 1994. p. 43 – 69.

HARVEY, Sylvia: Woman’s place: the absent family of film noir. In: KAPLAN, E. Ann (ed.): Women in film noir. London : BFI, 1989. p. 22 – 34.

KOZLOFF, Sarah: Overhearing Film Dialogue. Berkeley, Los Angeles : University of California Press, 2000. 332 p.

NORTON, Jonathan: Between the Violence and Virtue of Desire: Film Noir and Family Melodrama in the Transgeneric Cinema of Hollywood’s Late Studio Era. Ottawa (Ontario): Carleton University, 2004. (thesis). URL: curve.carleton.ca/system/files/theses/27324.pdf (visited 22nd of October 2022)

SCHRADER, Paul. Notes on Film Noir. In SILVER, Alain – URSINI, James (eds.): Film Noir Reader. New York : Limelight Editions, 2001. p. 53 – 63.