Abstract

This paper examines the revitalization of Hong Kong cinema in the post-pandemic era, focusing on the dynamic aesthetics, preservation of locality, and the emergence of a dehybrid style. By analyzing various contemporary Hong Kong films, this paper argues that the post-pandemic recovery period has facilitated new creative possibilities and a reconnection to the region’s unique cultural identity. The study also takes into account the historical trajectory of Hong Kong cinema, the impact of the global pandemic on Hong Kong film industry, and the sociopolitical factors that have shaped the industry’s response to these challenges.

Keywords: Locality, Dehybrid Style, Dynamic Aesthetics, Post-pandemic era.

Introduction

Hong Kong cinema is subject to a small market size, and the traditional and congenital population of its audience. Throughout its history, HK cinema has been nomadic, drifting between and incorporating various styles and market demands from nearby film industries; in particular, HK heavily depended on the Southeast Asian markets of Taiwan, Malaysia, South Korea, and Singapore during the 1950s and 1960s. By the 1980s, HK had entered its “Golden Period” of cinema, with some HK films (e.g., Jackie Chan films) reaching audiences as far away as Japan, Europe, and the United States.

Hong Kong cinema has also long been characterized by its distinctive blend of Eastern and Western influences, dynamic visuals, and a strong sense of local identity. However, the global pandemic caused significant disruptions to the film industry, leading to a period of uncertainty and decline. As the world enters the post-pandemic era, the Hong Kong film industry has shown signs of recovery, driven by a renewed emphasis on the dynamic aesthetics, locality, and a dehybrid style that diverges from the traditional East-meets-West paradigm. This paper aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of these trends while contextualizing them within the broader history of Hong Kong cinema and the challenges posed by the pandemic.

Reviewing the historical context and background of Hong Kong Cinema, Hong Kong Cinema has a rich and influential history that spans several decades. It emerged as a significant film industry in the 1950s and experienced its peak in the 1980s and mid-1990s, gaining international recognition for its unique style and diverse genres. Hong Kong Cinema has been known for its dynamic storytelling, innovative techniques, and blending of various influences from Chinese, Western, and other Asian film traditions. One of the defining characteristics of Hong Kong Cinema is its ability to adapt and evolve. Its success can be attributed to a combination of factors, including its talented filmmakers, movie stars, creative freedom, and a thriving local film market. The industry has been renowned for its prolific production, releasing a staggering number of films each year across a wide range of genres, such as martial arts, action, crime, romance, comedy, and supernatural. Hong Kong Cinema’s popularity grew exponentially in the 1970s and 1980s with the emergence of iconic actors and directors. Filmmakers like Wong Kar-wai, John Woo, Tsui Hark, and Jackie Chan gained international acclaim and brought Hong Kong Cinema into the global spotlight. Their distinct visual styles, narrative techniques, and innovative use of action choreography captured the attention of audiences worldwide. Moreover, Hong Kong Cinema has often served as a bridge between Eastern and Western cultures. It skillfully incorporated elements from both traditions, creating a unique hybrid style that appealed to a diverse audience. The combination of fast-paced action, intricate storytelling, and emotional depth made Hong Kong films highly popular not only in Asia but also in Western markets.

However, the industry faced challenges in the early 2000s due to various factors, such as the Asian financial crisis, rising production costs, and competition from Hollywood films. The industry experienced a great change in both local and international markets,

Data Analysis of Movie Box Office

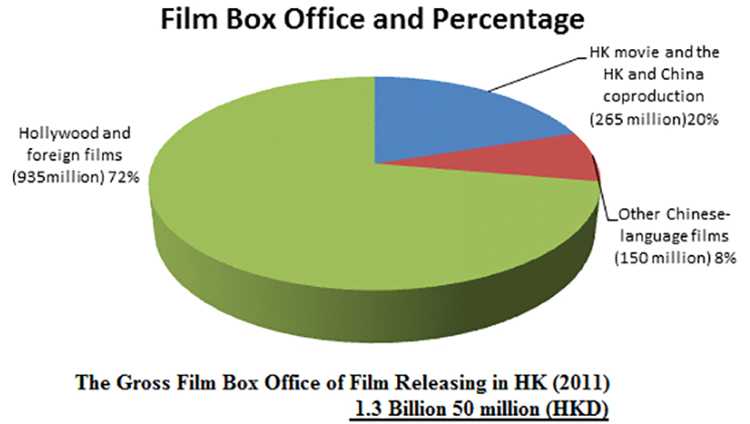

In 2011, Hong Kong (HK) cinema (including both HK movies and those coproduced with China) attained HK$265 million in total box office sales, of which HK$120 million (45%) was earned from “pure” HK films, and $145 million (55%) was earned from collaborative HK–China films. A quantity data analysis revealed that HK cinema produced 20 of 47 (43%) films released in 2011, and the remaining 27 (57%) were coproduced by HK and China. Furthermore, as 2011 closed, it was announced that You Are the Apple of My Eye (Ko, 2011) had grossed over HK$61,295,65,161 and became the all-time highest grossing Chinese film in the HK box office, a record previously held by Kung Fu Hustle (Chow, 2004), which had earned HK$61,278,697. 2 3 Additionally, the highest box office sales (HK$41,078,280) in 2011 were earned by 3D Sex and Zen: Extreme Ecstasy (Suen, 2011), a HK 3D erotic costume drama film; the lowest box office sales (HK$78,101) in 2011 were attained by Drugs 2 (HK–China film). Total box office sales earned from HK films (including both “pure” local HK movies and HK–China movies), was approximately HK$265 million (20%), and Hollywood and foreign films was approximately HK$935 million (72%) and other Chinese-language films was about HK$150 million (8%) of the gross box office sales (HK$ 1.35 billion) (see Figure 1).

Several implications can be drawn from the above data:

2011 was the first year that Taiwanese local films with small production budgets and scales broke the movie box office record in HK, indicating that fresh actors and new film directors were able to attract larger audiences; this was particularly true among the youth audience. For example, You Are the Apple of My Eye is a youth-oriented film with a healthy amount of romance and humor that tells a classic and typical love story about an odd couple who begin dating, quarrel, and lose each other but never forget their intimate relationship. By contrast, HK filmmakers remained dependent on the remakings of successful films from a variety of genres, including erotic films (e.g., 3D Sex and Zen: Extreme Ecstasy and The 33D Invader), costume romantic films (e.g., A Chinese Ghost Story, Mural, and Its Love), and martial arts and kung fu films (e.g., Wu Xia, Shaolin, and Overheard 2).

New HK filmmakers were not successful in 2011. For example, Lover’s Discourse (Tsang & Wan, 2011), The Way We Were (Ning & Ping, 2011), and Summer Love (Chin) only earned HK$2,075,832, HK$220,015, and HK$ 1,507,925, respectively. Notably, Chin had also produced Lan Kwai Fong, which earned HK$ 8,012,003. However, even established filmmakers who worked with new people performed badly in 2011, such as Wong Jing who worked with new filmmaker Patrick Kong. The sales of his four 2011 films are presented in Table 1).

| Film Title | Post | HK Box office (HK$) |

|---|---|---|

| Men Suddenly in Love 猛男滾死隊 |

Director, writer, producer | 4,699,651 |

| Treasure Hunt 無價之寶 |

Director, writer | 1,214,989 |

| Treasure Inn 財神客棧 |

Co-director with Corey Yuen, writer | 2,350,755 |

| Hong Kong Ghost Stories 猛鬼愛情故事 |

Co-director with Patrick Kong, producer | 683,991 |

So-called national celebration films, such as China 1911 and The Woman Knight of the Mirror Lake also performed badly in HK (HK$1,571,087 and HK$811,342, respectively). This was also true for HK–China coproduced films, including A Chinese Ghost Story (HK$4,344,324), Mural (HK$270,559), Its Love (HK$3,193,647), Wu Xia (HK$8,052,152), Treasure Inn (HK$2,350,755), Treasure Hunt (HK$1,214,989), White Vengeance (HK$1,292,756), Legendary Amazons (HK$42,000), East Meets West (HK$600,000), The Flying Swords of Dragon Gate (HK$5,047,574), Sleepwalker in 3D (HK$1,859,823), and Magic to Win (HK$3,000,000). Notably, several of these films earned substantially more in mainland China’s box offices, including The Flying Swords of Dragon Gate (RMB$412,200,000), Its Love (RMB$210,097,000), Shaolin (RMB$216,023,000), Mural (RMB$178,005,000), and White Vengeance (RMB$153,000,000), which reflects the difference of cinema taste and preference between Mainland China and HK film audiences. leading to a shift in production and distribution strategies. For examples, following its return to China, HK cinema producing “China and Hong Kong cooperation films” under the Closer Economic Partnership Agreement policy. Several film scholars and cultural critics have since commented that the contemporary HK Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) cinema industry has lost some degree of the original HK locality, spirit and creativity because of the over-dependance on China’s larger film market and the possibility of higher profit, and most HK filmmakers have moved their workshops and companies to Beijing to produce local films and forge relationships in China.

Most HK-produced films also performed poorly in 2011. For example, Let’s Go (HK$194,235), Turning Point 2 (HK$3,871,162), Lover’s Discourse (HK$2,075,832), The Way We Were (HK$220,015), Summer Love (HK$1,507,925), Hong Kong Ghost Stories (HK$683,991), Summer Love (HK$1,507,925), Microsex Office (HK$3,411,062), and Big Blue Lake (HK$4,516) all garnered minimal earnings at the box office. The few HK films that the passed the box office, such as Love is the Only Answer (HK$6,242,996), Lan Kwai Fong (HK$8,012,003), The Detective (HK$6,142,939), The Fortune Buddies (HK$6,520,514), Overheard 2 (HK$24,010,055), and Life Without Principle (HK$8,426,223), reflect the decreasing creativity and production quality of HK films.

Conversely, Fan’s (2012) analysis indicated that the total number of films produced in mainland China in 2011 was 791. Of these, 558 were feature films, 24 were animations, 26 were documentaries, 76 were science educational films, 5 were special topic films, and 102 were digital films produced by the TV movie channel. The total box office earnings were approximately RMB$13.1 billion, which was an increase over the RMB$10.2 billion earned in 2010; of this total, approximately 53.61% (RMB$7.31 billion) was earned from mainland-produced films, and approximately 46.39% (RMB$6.84 billion) was earned from foreign films.

Data Analysis of Cinema Theatres and Silver Screens

According to the State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television (Table 2) and Fan’s (2012) analysis, 803 new cinema theaters and 3,030 silver screens were built in 2011 (8.3 screen increase daily); by the year’s end, mainland China was home to a total of 2,803 theaters and 9,200 screens.

| Year | The gross film box office (RMB) | Number of Cinema Theatre | Number of Silver Screens |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 13.115 Billion | 2,803 | 9,200 |

| 2010 | 10.172 Billion | 2,000 | 6,256 |

| 2009 | 6,206 Billion | 1,687 | 4,723 |

| 2008 | 4,341 Billion | 1,545 | 4,097 |

| 2007 | 3,327 Billion | 1,427 | 3,527 |

Source: The State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television.

According to Next Media, 2012, the net profit of movie theaters (uncalculated human resources costs) is approximately 15% of the ticket price; the remaining 85% is divided between government tax and film distribution (50%) and theater businessmen. (35%). Although audiences in the past viewed the pirated and illegally downloaded films freely, contemporary white-collar workers and couples prefer watching movies in theaters and consider the social and dating activity evidence of high class taste. Furthermore, long rental contracts (12–18 years) for theaters in mainland China provide investors with a longer profit-making and return period (i.e., the first 5 years is the investment period). Compared with the short rental periods (8–12 years) and high rent in HK. Therefore, the profitability of China Film Market can be combined with a low labor salary, high RMB exchange rate, and high ticket prices, it is much more promising to invest in movie theaters in mainland China than in HK (see Table 3).

| Year | Number of Movie Theatre | Number of Silver Screen | Seats |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 119 | 188 | 121,885 |

| 1996 | 100 | 181 | 95,468 |

| 1999 | 70 | 185 | 75,092 |

| 2002 | 60 | 179 | 57,376 |

| 2005 | 75 | 207 | 50,686 |

| 2008 | 47 | 189 | 39,934 |

| 2011 (till July) | 47 | 204 | 39,674 |

The number of movie theater seats in HK in 2011 was 39,674, which was 3 times fewer than the 121,885 in 1993; additionally, the number of movie theaters decreased from 119 in 1993 to just 47 in 2011 (Cheuk, 2011). Conversely, the number of silver screens increased from 188 in 1993 to 204 in 2011. However, the overall theater industry in HK is dwindling, with the net profits earned by theaters from movie tickets only 5% of the total cost of the ticket, compared with the 15% net profits from movie tickets on the mainland. Furthermore, the 18-year-old UA Time Square theater closed on January 31, 2012; other theaters only schedule blockbuster and popcorn movies during golden screening periods to maintain profit, whereas small budget films, art films, and independent films struggle to gain any screening time.

Analysis of Asian Film Awards

As summarized in Table 4, three South Korean films (The Host, Secret Sunshine, and Mother) won the Best Film award in 2007, 2008, and 2010, respectively; in addition, the Japan–The Netherlands–HK film Tokyo Sonata (2009) and Thai film Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2011) won the Best Film award in their respective years. No HK film director received the award for Best Director between 2007 and 2011, and only one Best Actor award (Tony Leung for Lust, Caution, 2008) and two Best Supporting Actor awards (Nicholas Tse and Sammo Hung for Bodyguards and Assassins (2010) and IpMan 2 (2011) respectively have been won by HK films. This suggests that the artistic and cultural quality of HK films is not up to par with other films produced in Asia. Whereas HK film dominated the Southeast Asian market in the past, however, South Korea and mainland China films are now notably more popular and successful.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asian_Film_Awards#Major_award_winners

Sex, Gambling, and Drugs in Hong Kong Cinema during the Post CEPA

The continued downfall of HK cinema has critically damaged the creative and production abilities of HK filmmakers. Contemporary HK cinema can be regarded as the era of sex, gambling, and drugs, with the production of local, small-budget films, such as The Way We Dance (Ping, 2013), nearly extinct in the HK film industry. Without a big-name cast, box office guarantee, or famous film director, a movie is considered too risky to invest in; instead, HK filmmakers focus on special effects, action, and sex to garner and entertain audiences and ensure a profit. Hence, common film genres and topics in HK today can be classified into sex and eroticism, gambling, and drugs and the underworld society. Recent sex- and erotica-themed films include Lan Kwai Fong (Chin, 2011), Sex Duties Unit (Mak, 2013), 3D Sex and Zen: Extreme Ecstasy (Suen, 2011), Due West: Our Sex Journey (Wu, 2012), Girl$ (Bi, 2010), May We Chat (Yung, 2013), Whispers and Moans (Yau, 2007), True Woman for Sale (Yau, 2008), Golden Chicken 3 (Chow, 2014), AV (Pang, 2005), Naked Ambition (Lam & Chan, 2003), Enthralled (Tsao, 2014), and Men Suddenly in Love (Jing, 2011). Recent gambling-themed films include Kung Fu Mahjong 3 - The Final Duel (Jing, 2007), Mr. and Mrs. Gambler (Jing, 2012), and From Vegas to Macau (Jing, 2014). Finally, recent drug- and underworld-themed films include Protégé (Yee, 2007), Drug War (To, 2012), and The White Storm (Chan, 2013).

Notably, the rise of these sex-, gambling-, and drug-centered films, to the detriment of other genres, can be linked with the implementation of the CEPA policy. Post-CEPA, the HK cinema industry has experienced substantial economic pressure and cultural marginalization, facilitating the emergence of a market that embraces female exploitation, and tasteless storylines. The cultural values and human literacy of the Wenyi film tradition (i.e., literature and art films) no longer receives commercial value; therefore, the few persistent HK filmmakers (e.g., Ann Hui, Mabel Cheung, Alex Law) have largely shifted to mainland China’s film ecology to continue creating Wenyi films. For example, Ann Hui’s film The Golden Era is currently in production, starring Tang Wei and Feng Shaofeng; the story follows Xiao Hong, a 1930s author who was one of the most influential female writers in contemporary China.

Furthermore, this film cultural shift has generated another problematic phenomenon: most problematic roles and negative situations on screen are played by HK actors and occur in HK society. For example, Overheard (Mak & Chong, 2009) is the dirty inside story of a stock exchange market in HK. Drug War follows a police captain, Zhang Lei (played by Chinese actor Sun Honglei), who partners with drug lord Timmy Choi (played by HK actor Louis Koo) after he is arrested. To avoid the death penalty, Choi agrees to reveal information about his partners, who operate a methamphetamine ring; however, Lei quickly grows suspicious of Choi’s honesty after several police officers conduct a raid on the drug ring. The Patriot Yue Fei (2013), a mainland China TV series, tells the story of a treacherous Song minister, Qin Hui (played by HK actor Gallen Lo Ka Leung) who had a prominent role in the death of Yue Fei (played by Chinese actor Huang Xiaoming), a Song general who was known for resisting invaders during the Jin Dynasty.

Pandemic Impact on Hong Kong Film Industry

The global pandemic has had significant effects on the production and distribution of Hong Kong cinema. Here are some of the key ways the pandemic impacted the industry: from perspective of film production, Delayed or halted projects: Many film productions were delayed or halted due to the pandemic, as lockdowns, social distancing measures, and travel restrictions made it extremely difficult for film crews to work together and film on location. This disruption led to a decrease in the number of films produced during the pandemic. Health and safety protocols: Filmmakers had to adapt to new health and safety protocols to protect the cast and crew from the virus. These measures included regular testing, wearing personal protective equipment (PPE), and implementing strict hygiene practices on sets. This added complexity and additional costs to film productions. Budget constraints: The pandemic’s economic impact led to a decrease in funding and investment in the film industry. Filmmakers had to navigate budget constraints, which may have affected the scope and quality of some projects.Casting and crew challenges: Travel restrictions and quarantine requirements made it difficult for filmmakers to secure international talent or crew members for their projects. This may have resulted in more localized productions or creative workarounds.

From the film distribution angle, Theatrical releases: With temporary closures of cinemas and social distancing measures in place, theatrical releases became challenging. Many films were postponed or released with limited screenings, which significantly impacted box office revenues.Film festivals and markets: The pandemic forced the cancellation or rescheduling of many film festivals and markets, which are crucial for promoting and selling films to international buyers. This disruption affected the visibility and reach of Hong Kong cinema on a global scale. Shift to online platforms: With the decline of theatrical releases, there was a notable shift towards online platforms and streaming services. Many films were released directly on streaming platforms or held online premieres. While this provided a new avenue for film distribution, it also led to increased competition with other content available on these platforms.Hybrid distribution models: The pandemic has accelerated the adoption of hybrid distribution models, where films are released simultaneously in theaters and on online platforms. This approach allows filmmakers to reach a wider audience and potentially maximize revenues, despite the challenges posed by the pandemic. In summary, the pandemic has had a significant impact on the production and distribution of Hong Kong cinema, leading to delays and disruptions in the filmmaking process and the way films are released and consumed. However, the industry has shown resilience and adaptability, with filmmakers finding new ways to produce and distribute their work in the face of these challenges.

The Post-Pandemic Recovery of Hong Kong Cinema

In 2019, the rising of global pandemic even worse HK film industry. the research examines the impact of the global pandemic on Hong Kong cinema, with a focus on the temporary closures of cinemas, disruptions to film production and distribution, and the financial challenges faced by the industry. It also highlights the role of the pandemic as a catalyst for change, prompting a reevaluation of the industry’s priorities and creative direction.

The most significant aesthetic is the Locality: Reconnecting with Hong Kong’s Cultural Identity. the increasing emphasis on locality in post-pandemic Hong Kong cinema, with a focus on the judicial themes and legal system that resonate with Hong Kong audiences with the unique social issues and concern. For examples, The Sparring Partner is a 2022 Hong Kong legal affairs crime thriller film directed by Ho Cheuk Tin in his directorial debut. The film stars Yeung Wai Lun, Mak Pui Tung, Louisa So, and Michael Chow with Jan Lamb and Gloria Yip listed as special performers. The story is adapted from the 2013 Tai Kok Tsui double parricide and dismemberment case. The film was premiered at The 46th Hong Kong International Film Festival. It was approved by the Film Development Fund with a financing amount of HK$2.5 million. and released by Golden Scene and Mei Ah Entertainment. The film was officially released in Hong Kong on October 27, 2022. It earned HK$43 million and becomes the tenth highest-grossing movie of 2022 in Hong Kong. A Guilty Conscience is a 2023 Hong Kong mystery crime comedy film written and directed by Jack Ng, in his directorial debut. It stars an ensemble cast including Dayo Wong,Louise Wong and Tse Kwan-ho. The plot follows a court of a single mother (Louise Wong) charged with the murder of her daughter, and an attorney (Dayo Wong) vows to clear her name after a mistake resulted the mother’s wrongly sentence. A Guilty Conscience was released on 21 January 2023, coinciding with the Chinese New Year’s Eve. It received acclaim for its screenwriting, direction and acting, particularly that of Dayo Wong, Louise Wong and Tse. The film grossed HK$114,293,675 and became the highest-grossing Chinese film in Hong Kong till now, surpassing 2022 film Warriors of Future.

These two films address issues such as legal system, equality, fairness, the class struggle and difference between the rich and the poor, etc. which have contributed to this renewed focus on locality, including the ongoing debates surrounding Hong Kong’s identity and the influence of external forces on the region’s cultural landscape. The story of films are also based on Hong Kong true events symbolizing the rising of social realism after the post-pandemic era. As Hong Kong society faces significant social and economic changes, filmmakers may turn to social realism as a means to explore pressing issues and reflect the dramatic experiences of everyday people. Films in this genre often address topics such as social inequality and identity struggles within the context of Hong Kong’s unique cultural landscape.

Dehybrid Style: Breaking Away from the East-meets-West Paradigm, The emergence of a dehybrid style in post-pandemic Hong Kong cinema is characterized by a deliberate move away from the traditional East-meets-West paradigm. The reasons behind this stylistic shift includes the desire to assert a distinct cultural identity and the influence of new creative forces in the industry. for instance, some emerging young filmmakers, Oliver Chan Siu-kuen: Oliver Chan is a promising young director who made her feature debut with “Still Human” (2018). The film tells the story of a disabled man and his domestic helper, exploring themes of empathy, humanity, and social prejudice. Chan’s sensitive portrayal of her characters and their struggles is indicative of a new voice in Hong Kong cinema that focuses on intimate, character-driven stories. Wong Chun: Wong Chun is another emerging talent in Hong Kong cinema, having directed the critically acclaimed film “Mad World” (2016). The film addresses the issue of mental illness and its impact on individuals and their families, showcasing Wong’s ability to tackle complex social issues with nuance and insight. Their film style tends to be indie and art-house films, with the innovative narrative structures, visual styles, and subject matters that may not fit into the mainstream commercial cinema, but showcasing the ways in which these films incorporate elements that are uniquely Hong Kong, such as local dialects, folklore, and cultural references. It also considers the potential implications of this dehybrid style for the future of Hong Kong cinema, in terms of both creative possibilities and audience reception.

Conclusion

Despite the varied challenges, the industry continues to produce critically acclaimed films, demonstrating its resilience and creativity. Today, Hong Kong Cinema stands at a crucial juncture as it faces the recovery period after the COVID-19 pandemic. The industry must navigate the changing landscape of film production, distribution, and audience preferences while preserving its unique identity and cultural heritage. By understanding the background and evolution of Hong Kong Cinema, we can appreciate its significance as a vibrant and influential film industry that has left an indelible mark on global cinema. With the role of government support and industry collaboration in facilitating the recovery and future growth of Hong Kong cinema, with a focus on the policies and initiatives that have been implemented to support local filmmakers, encourage investment, and promote the industry both locally and internationally.

Moreover, the recovery of Hong Kong cinema in the post-pandemic period has been characterized by a revitalization of dynamic aesthetics, a reemphasis on locality, and the emergence of a dehybrid style. These trends not only signal a rebirth of the industry but also reflect a broader desire to reconnect with and preserve Hong Kong’s unique cultural identity. As the world continues to grapple with the long-term effects of the pandemic, the resilience and adaptability demonstrated by Hong Kong cinema serve as a testament to the region’s enduring creative spirit. Moreover, the industry’s ongoing evolution in terms of new voices, genres, and distribution models suggests that Hong Kong cinema is well-positioned to navigate the challenges and opportunities of the post-pandemic world, ensuring its continued relevance and vitality for years to come.

Final notes

1Dr. Chan Ka Lok Sobel, Senior Lecturer and the Best Director in London Film Award.

2《那些年》香港票房超《功夫》成華語片最高” (in Chinese). mtime Movies. 2012-01-01. http://news.mtime.com/2012/01/01/1479092.html. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

3“You are the Apple of My Eye: Hong Kong Box Office Surpasses Kung Fu, Becoming the Highest Grossing Chinese Film.” Mtime Movies, January 1, 2012. http://news.mtime.com/2012/01/01/1479092.html (accessed January 3, 2011).

Bibliography

卓伯棠( 2011 )。〈國內電影院銀幕高速增加. 香港戲院業前景則令人憂心〉。《傳媒透視》( 2011,12 月號 )。

Cheuk, Pak-tong. 2011. “Rapid Increase of Cinema Screens in Mainland China, But the Outlook for Hong Kong’s Theater Industry is Worrisome.” Media Digest, December 2011 issue.

范麗珍( 2012 )。〈 2011 十大影片院綫地區票房普增十大影城變陣〉。載於《中國電影報》 ( 2012 年1月19日第8-10版 )。

藝恩網站。http://column.entgroup.cn/12682.shtml

Fan, Lai-zhen. 2012. “Top Ten Films of 2011: Box Office Increases Across Regional Theatrical Circuits and Changes in the Top Ten Cinemas.” China Film News, January 19, 2012, pages 8-10. EntGroup website. http://column.entgroup.cn/12682.shtml

Next Media. 2012. “Cinema Business in Mainland China.” In Next Media, 60-62. Hong Kong: Next Media, February 2, 2012.

Webgraphy

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asian_Film_Awards#Major_award_winners