Abstract

Queerbaiting is a topic that has become recurrent in contemporary discussions concerning Hollywood’s treatment of on-screen queer representation. Adopted by fan communities online to describe the phenomenon of baiting queer audiences with the promise of queer content, namely with queer subtext in film and television, it has not been sufficiently explored within an academic framework. This study revises literature done on Queerbaiting so far, updating it by proposing a structured approach to the different layers that compose this phenomenon - text, audiences, and authorship. By placing Queerbaiting within its historical context, its deep-seated roots in Hollywood become clear, as well as the way it has conditioned queer audiences through time. Furthermore, Queerbaiting’s most problematic aspect - establishing authorial intent - is dissected to find one possible solution, based on a moderate intentionalist framework.

Keywords: Queerbaiting, Queer Theory, Intentionality, Implicit Meaning, Active Spectator.

Introduction

Queerbaiting is a relatively recent term, scarcely academically explored, but increasingly relevant within fan forums and even film journalism and critique (Nordin 2019, 38). It is a wide-reaching, controversial and topical discussion at a time where representation in media and identity politics dominate the film and television discourse. Brennan (2019) defines Queerbating as a “form of “covert courting” of queer followings”, through “strategies opposed to open, or explicit, queer marketing” (p.4). Queerbaiting can range from audiences believing characters are being written as implicitly queer without ever being made overt; studios hinting at queer characters in promotion campaigns pre-release but the result being underwhelming or non-existent, and even giving overt queer characters unsatisfactory or harmful arc resolutions (Brennan, 2019; Nordin, 2019; Eve Ng, 2017). The presupposition of Queerbaiting as an intentional act by producers is a key element: when Brennan (2019) talks about “courting” he means conscious deceit of audiences, linking it heavily to marketing strategies. Intentionality is, therefore, the most central aspect of Queerbaiting. It is what the “baiting” half of the word is all about, and it is what made fans start this discussion in the first place - the idea that they are being tricked on purpose.

The target of this article is primarily the intratextual use of coding to hint at a character’s queerness without ever making it explicit. I argue that labeling a text as Queerbaiting is dependent on three main players: the text (the film or television show that does the baiting), the audience (the queer viewers who feel baited), and the author (the creator or producer accused of baiting). Concepts and theories addressed throughout are applied to the case study of Disney’s Frozen franchise (Chris Buck and Jennifer Lee, 2013, 2019).

Despite the growth in (explicit) LGBT+ stories and filmmaking in Hollywood and the rise of politically charged discussions about the exploitation of queer audiences (with Queerbaiting at its centre), coding a character as queer is still an effective way to get queer audiences to watch a film, without alienating the public that is not as receptive to these types of stories. This is true, especially if we consider Hollywood’s global market demands and the distribution of films to countries that are hostile to any non-cis-heterosexual identity expressions. This leads to the production of “‘texts’ that are highly ambiguous, or permeable when it comes to assigning meaning” (Elsaesser 2011, 247) with the end goal of appealing to as many people as possible.

For all these reasons, and because I believe that research on Queerbaiting in film has been relatively neglected when compared to its small-screen counterpart, this article was written primarily with cinema in mind. Nonetheless, I hope the research I have carried out can be applied to all media to some degree.

Riddle Me This: The Text

The Riddle: Historical Background And Relevant Concepts

Elsaesser (2011) brings forward the notion of Hollywood’s “access for all” based on the industry’s tradition of a “structured ambiguity”. Classical Hollywood, Elsaesser notes, “excelled in creating movies that were ambivalent and even duplicitous, without becoming incoherent” (p.248). This was done both so creatives could breach the stifling Motion Picture Production Code (MPPC) rules in inconspicuous ways and to ensure movies made as much money as possible at the box office, by being “emotionally and intellectually” accessible to audiences from all backgrounds, “in the form of identification and (self-)recognition” (p.248), despite the narratives being seemingly overwhelmingly conservative, white and heterosexual.

Film Noir, for example, particularly thrived under blurred lines, mystery, and the “feeling of not knowing” (Dyer 2002, 110), making it a fitting ground for ambiguous characters and themes, namely regarding sexual orientation. Furthermore, Noir started a tradition of sexually ambiguous criminals and villains that still has ripples in American film today.

Ambiguity in storytelling is, then, in Hollywood’s foundations, and its power, to this day, as the biggest cinematic industry on the planet, lies precisely in the careful administration and maintenance of this plurality of meanings (Elsaesser 2011, 256). Hollywood must cater to markets all over the world, with different and deeply sensitive cultural and moral differences.

Queer coding, as in implicit queerness in a film’s characters and themes, or what Benshoff and Griffin (2005) refer to as “connotative homosexuality” (p.17), is one of the most commonly used and most long-lasting strategies employed to achieve this duplicity. Queerness has been trapped in a “connotation” closet for “far too long”, which has allowed “straight culture to use queerness for pleasure and profit in mass culture without admitting to it” (Doty 1993, xi-xii).

For the purposes of this project, I anchor the term “queer” to personal identity, both of gender and sexual orientation, and use it to signify all that stir from the dominant cis-heterosexual ones. As an umbrella term, it encompasses several micro-identities, each with its own problematics.

Gayness on film and gayness in everyday life are linked in the sense that “the story of the ways in which gayness has been defined in American film is the story of the ways in which [gay people] have been defined in America” (Russo 1981, xii). The representations of the LGBT+ community on screen, implicit or otherwise, reflect society’s own perception of them and evolve through time.

Benshoff and Griffin (2005) offer a map for the definition of the “queer film” category: a queer film can be defined by its content when it has queer characters and touches on queer issues; it can be defined by its author if they are queer themselves; by its audience, in the event that, even if the film does not fit these first two categories, it still finds a place in queer culture through camp readings; by its genre - the authors give horror and musicals as an example of queer genres; or more generally by film’s specificities as a medium whose viewing experience is grounded in “identification with characters that are a different race, gender or sexuality”, thus becoming a queer experience in and of itself. Most often, though, “all these ways of defining a queer film tend to overlap and blur together” (pp. 16-18).

Queerness has, then, been part of film since its very creation, but Hollywood grew and developed in an environment that was against any overt expression of it, both on-screen and by its audiences. Explicit same-sex attraction fell under the aforementioned MPPC rule against “sex perversion”, which made it impossible for queer characters to exist on-screen. Although adherence was technically voluntary, producers had to abide by these rules if they wished to have a successful roll-out and “[stave] off pressure groups” (Brooke, n.d.). However, filmmakers would code their characters in ways that would result in them being read as queer by audiences, without having to explicitly state or show it.

This type of coding falls under David Bordwell (1989)’s categorisation of “implicit meanings”. The author differentiates these from “symptomatic meanings”, i.e. unintentional or involuntary meanings, linked to notions of repressed trauma found in psychoanalysis, that end up manifesting themselves in an author’s creation. Considering that intentionality is a central aspect of the type of queer coding Queerbaiting entails, symptomatic meanings fall outside my object of study. Albeit remaining implicit, i.e. never actually confirmed through lines of dialogue or explicit physical affection, queer coding is usually, then, made quite obvious through other means.

The Clues: How Is Queer Coding Done?

Russo (1981) astutely points out that “homosexuality in the movies,” whether or not overt, “has always been seen in terms of what is or is not masculine” (p.4). This gives us our first, and one of the most obvious clues for queer coding: gender (or its reversal).

In the first half of the 20th Century, homosexuality was regarded as something inherently connected to gender - homosexual men were understood to be men that wished to be women and vice versa, and this was mirrored in the movies. One of the earliest ways to code a male character on film as queer was, thus, to present him as overly effeminate or what Russo (1981) categorises as “the sissy”. The sissy’s effeminacy was “used on-screen and off, as both scapegoat and weapon, to expose a mistrust of brightness or wit in men who were not also pushy or aggressive” (Russo 1981, 32).

Similarly, lesbians were defined by their excessive masculinity through the tomboy category. Their sexuality reduced to their wish to appear as men and act like men, essentially to be more like the “stronger sex”:

Tomboys (and the very idea of lesbianism) emerged as an exotic and often fascinating extension of the male myth, serving as a proving ground for its maintenance. True lesbianism, relationships defined by and in terms of women’s needs and desires, was not contemplated (Russo 1981, 6).

Neither sissies nor tomboys had identities of their own. Their existence on-screen served the heterosexual man always, either as a warning or as gratification, and their sexuality was never explicit or even there at all. However, this set the grounds for how gay men and women would come to be represented in film for the decades that followed, which leads to the second clue for queer coding: stereotyping.

By the mid-20th Century, these stereotypes founded on the confusion between sexual orientation and gender identity had become so ingrained in culture they were obvious means to identify queer characters on screen:

The males are fastidiously and just a little over-elaborately dressed, coiffed, manicured and perfumed, their speech is over-refined and their wit bitchy, and they love art, antiques, jewellery and cuisine. (...) Females are large, big boned or fat, have cropped or tightly drawn back hair, wear shapeless or else highly tailored clothes and generally work for a living (Dyer 2002, 97).

Other stereotypes that could be found in queer coded male characters were an excessive attachment to a mother figure and “the adoration of women”, “aestheticising them and treating them as beautiful creatures” (Dyer 2002, 100, 98).

Because queerness is not something that is inherently part of one’s physical attributes (like race or sex, for example), it is much harder to make visible. Stereotypes - generally shared by society - were, therefore, the easiest way to code (homo)sexuality (Dyer 2002).

However, as general audiences became more aware of what homosexuality was, they were quicker to associate these effeminate or masculine characters with it. The foregoing stereotypes became, then, too obviously homosexual to get censors’ seal of approval. One way to get implicitly queer characters through censorship was to turn them into something perverted and evil that fit the conservatie religious beliefs of the time:

It did not matter much to the censor that you could read Joel Cairo (Peter Lorre)’s homosexuality between the lines in The Maltese Falcon (John Huston, 1940) provided that Cairo was presented as a dangerous and/or ridiculous delinquent. Something similar can be said of Waldo Lydeker in Laura (Otto Preminger, 1944), the housekeeper in Rebecca (Alfred Hitchcock, 1940) or the prison matron played by Hope Emerson in Caged (John Cromwell, 1950) (Mira 2011, 20).

A third clue, then, for queer coding is villainy. Villains’ criminal or psychopathic behaviour was an advantageous trait to associate with queerness as something inherently wrong. This made Film Noir, for example, a queer-prone environment. Hitchcock, who was obsessed with the perverted, was a big fan of the gay coded villain: one can add Rope’s Phillip and Brandon (1948), Strangers On a Train’s Bruno (1951), or Psycho’s Norman Bates (1960) to previously mentioned cases.

Dyer (2002) argues that because Noir, as a B-genre in Hollywood, was less surveilled and controlled, aimed at mature audiences, more experimental, and especially interested in the sexual and decadent, it was common for it to be populated by queer coded characters. Gilda (Charles Vidor, 1946), Kiss Of Death (Henry Hathaway, 1947), The Big Sleep (Howard Hawks, 1946), or Dead Reckoning (John Cromwell, 1947) are mentioned by the author as examples.

Lesbian coded characters were, similarly, presented as “neurotic and cold”, “their behaviour (...) often pathological”, “seen as women trying to be men while in reality needing a man” (Russo 1981, 100). To complete previous examples there are two coded Sapphics put forward by Russo (1981): Amy North in Young Man With A Horn (Michael Curtiz, 1950) or Eve Harrington in All About Eve (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1950).

The villainous queer is one of the most ingrained queer coded tropes in Hollywood, and can still be easily found in contemporary mainstream culture. One such example is Disney’s array of stereotypical effeminate male villains such as Jafar from Aladdin (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1992), Scar from The Lion King (Rob Minkoff, Roger Allers, 1994), Ratcliffe from Pocahontas (Mike Gabriel, Eric Goldberg, 1995) or Hades from Hercules (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1997). Even Ursula from The Little Mermaid (Ron Clements, John Musker, 1989) was based on the real-world drag queen Divine.

If not psychopathic, then queer characters could also be identified by a fourth clue: self-hatred. Another effective way to make queerness more acceptable in the eyes of the censors was to make coded characters depressed and even suicidal as a way to show just how unacceptable being gay was. Paul Newman’s Brick Pollitt in Cat On A Hot Tin Roof (Richard Brooks, 1958) and Sal Mineo’s Plato in Rebel Without A Cause (Nicholas Ray, 1955) are two such cases. Much like the villain, the depressed queer remained a recurrent image in American film. From Children’s Hour (William Wyler, 1961) to Brokeback Mountain (Ang Lee, 2005), even as they became explicit, queer characters were almost always given storylines that dealt with extreme self-hatred and emotional and physical violence.

The aforementioned Plato is one of the most notorious implicitly queer characters in cinema and a good segway to a fifth clue: the buddy relationship. This is a complex dynamic, responsible for endless queer readings. Homoeroticism can come naturally in same-sex friendships - like Plato and Jim’s -, especially if characters of the opposite sex are less prominent in the narrative. Specific same-sex settings such as prison, the army, or boarding schools “can create a degree of same-sex eroticism (...) all of its own” (Brennan 2019, 6). This has been described as “situational homosexuality”, an outdated term that entails temporary homosexual attraction brought on by all these extraordinary conditions. Exactly because of this kind of natural occurrence of homoeroticism, buddy relationships are often read as queer.

Mira (2011) mentions a term coined by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick (1990) that expresses this duality more accurately: “homosociality”. This extends queerness beyond just sexual acts, encompassing other expressions of same-sex attraction. This concept expanded the way queer representation, as well as the role of audiences and authors in its creation, started being studied (Mira 2011, 26).

The buddy relationship is, precisely, at the source of most media accused of Queerbaiting today. Making two friends of the same sex intentionally more-than-platonic (without actual realisation) is easy to deny through the “inherent homoeroticism” justification and it does not rely on reductive stereotypes, which makes it more tolerable to a modern audience. It is a successful way to keep a conservative audience, whilst simultaneously maintaining queer spectators, who are invested in these friendships. Therefore, longing stares, sexual innuendos, or suspiciously long or gentle touches became common practice in queer coding. Pitch Perfect’s Beca and Chloe (Jason Moore, 2012) are weirdly sexual with one another - even sharing a scene naked in the shower - whilst simultaneously both being very straight with very straight love interests. Signature quote from the Steve and Bucky pairing in the Captain America Franchise (2011, 2014, 2016)2, “I’m with you ‘till the end of the line”, has become a landmark for quotes that would undoubtedly be considered romantic if they had been shared between characters of the opposite sex. Poe and Finn from the Star Wars sequel trilogy (2015, 2017, 2019)3 stare at each other for a little too long with a little too much intensity, and in Ocean’s 8 (Gary Ross, 2018), Debbie and Lou feed each other breakfast lovingly and keep mentioning an undefined shared past that sounds like something slightly more serious than just a partnership in crime. The queer coding strategy is, then, far from recent but, what has changed with the Queerbaiting discussions that are happening today is that audiences are holding authors accountable for keeping their queer characters implicit. They believe, with society becoming increasingly accepting of LGBT+ expressions, that there is nothing holding creators back from giving the viewers the representation they are looking for in an explicit manner.

Solving The Puzzle: The Audience

The Scavenger: Specificities Of The Queer Spectator

As implicature, coding presupposes a reader on the other side that can decipher clues, read between the lines, and generally see beyond the explicit, immediate messages in the text.

Hollywood’s use of queer coding previously exposed is telling of what has been the queer spectator’s place and relationship with Hollywood movies, historically - that of a scavenger for clues.

Michael DeAngelis (2001) refers to the psychoanalytical melodramatic mode of fantasy, and the associated processes of identification and desire, to explain the gay spectator’s experience when appropriating certain characters or celebrities. The particularity of the gay spectator as the subject of the fantasy lies in the fact that the processes of identification and desire when relating to the object (character/actor) tend to overlap. Because they are attracted to people of the same gender, the queer viewer can see themselves in a particular character and relate to their experiences, but they are also more likely than the heterosexual viewer to sexually desire that same character, thus creating a more passionate bond.

Ambiguous characters with ambiguous sexualities sustain accessibility for queer fans to construct their fantasy accordingly, be it based on processes of identification or desire, or both. Due to a history of invisibility in media and society, the gay fan develops an ability to find pieces of themselves throughout different texts, appropriating them to form a sense of their own selfhood.

David Bordwell (1985)’s model of the active spectator can also be applied here. The queer spectator’s schemata from “everyday experience” will make them significantly more attuned to a text’s latent homoeroticism, whilst their schemata derived from “other artworks” (p.32) will manage their expectations that it could ever be resolved on screen.

The 21st Century queer (western) spectator, though, has a different set of schemata derived from their experiences in a more accepting society as well as a background of (explicit) queer cinema. This is helpful in understanding the difference in reactions to unresolved queer coding or homoeroticism from throughout the 20th Century to the present day.

LGBT+ viewers of the 2010s and 2020s were the first demographic to grow up on a significant number of explicit queer representations in popular culture. Audiences who now knew that overt gay representation was a possibility, started developing a much lower tolerance for subtext, especially if they felt that it was being built into narratives intentionally, as a means to get them to watch a particular production. The Queerbaiting debate emerges from this collective displeasure with Hollywood’s insistence on maintaining their characters’ queerness in the subtext.

Concurrently, the internet brought changes to the way content is distributed and appropriated by audiences and facilitated direct contact with creators. It became a vehicle for participant fan culture, actively engaged with the works they consumed, as well as a growing forum for political and social activism. Queerbaiting was born out of the combination of both these tendencies, allowing queer audiences to carry out a form of activism through the television shows or movies they were consuming, by demanding better treatment of queer representation. The queer fan begins demanding accountability from producers and creators in Hollywood who they believe no longer have a reason to keep their queers hidden and coded, shining the spotlight back on them as the ones that hold the power to create representation and visibility.

It is worth noting, nonetheless, that the ambiguity that results from queer coding is a big reason as to why queer audiences, at the same time as they criticise them, seem to flock to productions that keep any expression of homosexuality in the shadows, at a time where they do exist, explicitly, elsewhere. Contradictory texts elicit a bigger “ontological commitment” from fans when deciphering them, thus creating a stronger “affective bond” (Elsaesser 2011, 260) and leading fans to ferociously defend their view as the right view. The process of defending their own particular interpretation of a text, as well as the motivation to change it, paradoxically create a more ardent fanbase.

Todd Berliner (2017), however, mentions the importance of keeping “spectators motivated to continue the search for understanding” (p.57), meeting them in the middle. Hollywood’s complete inability to confirm queer fans’ expectations so as to preserve mass appeal led to viewers’ saturation and subsequent backlash, thus originating the Queerbaiting conversations.

Can The Culprit Be Found?: Authorship

The Source: The Issue Of Authorial Intent In The Queerbaiting Debates

Queer fans’ growing frustration with Hollywood’s sidelining of queer meaning to subtext led them to enact what Nordin (2019) describes as a revival of the author (p.28). She uses this expression in contrast with Barthes’ The Death Of The Author (1967) essay where he defends an anti-intentionalist position, placing the power over meaning on the reader exclusively. This revival of the author is a layered, complex process, though, that does not simply place the power over meaning back on the author. Audiences maintain a certain entitlement over a text’s meaning, but they also become acutely aware of the power creators have to manipulate the process of interpretation.

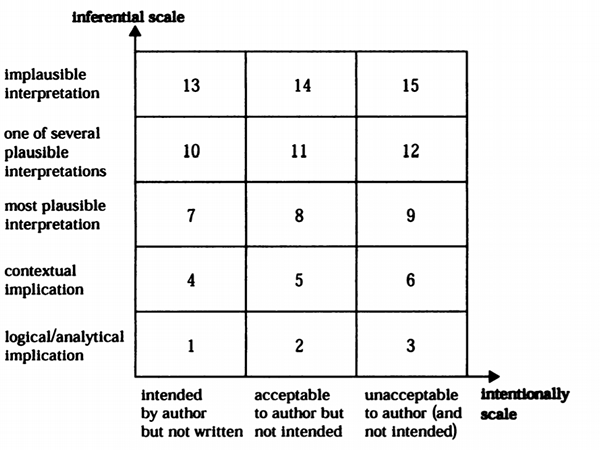

This is what Livingston (1998) defines as “moderate intentionalism,” which distributes meaning-making between author and reader. In this same vein, Gert Helgesson (2002) delineates two dimensions that intersect in deciding what is implicit in a determinate text: the reader’s interpretation and the author’s intention. I argue that Queerbaiting falls under the 10th category in Helgesson (2002)’s analytical scheme which describes “one of several plausible interpretations”, “intended by author but not written” (p.47). She argues that “we should assume that [the author] is right” when attributing meaning to their work, “unless we can show that what [they say] on the particular matter is inconsistent or otherwise does not fit with the rest” (p.41), provided proof used is well enough founded.

Figure 1. Helgesson (2022)’s “two-dimensional analytical scheme of the meanings of “implicit”” (p.47).

As mentioned, the reasons behind keeping queer meanings coded (financial consequences, social disapproval) keep authors from ever stating their deliberateness. This makes establishing intent, a vector that is so central to the entire Queerbaiting discourse, a particularly difficult task.

Doty (1993)’s conceptualisation of queer authorship also sheds some light on queer spectators’ specific kind of authority over meaning. Queer authorship is born out of an “interplay of creators, cultures, and audiences” (p.24). This means that, due to the particularities of queer history in cinematic productions (i.e. closeted creators and closeted audiences operating within a hetero-patriarchal society), deciding what artworks are or are not queer can not, pragmatically, come down to a single authority. Instead, affirming that something is of queer authorship combines not only auteurs but every person or institution who interferes with production (screenwriters, stars, studios, etc.), the predominant culture it is produced within, and the subculture of the spectators who appropriate it as queer. Queerbaiting as a discursive phenomenon is heavily based on this notion of queer authorship.

In addition, queer audiences who engage in the Queerbaiting discourse, and put its activist goals into motion, do so through a particular mode of reception - that of fandom. Jenkins (2012) describes fandom as a type of “participatory culture” that sees fans negotiate the meanings of different texts with their makers, “seeking to influence [it] where they may” (p.xxi). As groups, this process of meaning-making within fandom is “deeply social” (p.xiv), abiding by conventions and based on communal discussions. Fandoms’ wide-reaching interpretations of a piece of media, albeit popular and non-academic, are very much valid because of their shared character.

The authority over meaning in Queerbaiting debates is, thus, paradoxical. Fans feel they are entitled to their say over the text’s meaning but also actively pursue confirmation of their readings from creators, primarily in order to establish the exploitative nature of the Queerbaiting strategy. De Certeau’s “poaching” analogy, as adopted by Jenkins (2012), highlights the conflicting interests of producers and consumers, by borrowing from the power differential between “landowners” and “poachers”. However, it also acknowledges ways fans may challenge constraints over the production and circulation of popular meanings (p.32).

Queerbaiting is a symptom of fandoms’ general movement towards balancing the producer/consumer dynamic, by asking that their opinions be considered in the production process as the source of a work’s commercial and cultural success. With the advent of social networks, fandoms now have a direct line to creators and their criticism becomes harder to ignore, especially when mobilised towards a common, greater goal, such as the improvement of LGBT+ representation in media. As Jenkins (2012) notes, this democratisation of media consumption and discussion has basically forced media industries “to embrace more participatory strategies” (p. xxii), adding that “the ‘digital revolution’ has resulted in real, demonstrable, shifts in media power, expanding the capacity of various subcultures to access the means of media production and circulation” (p.xxiii).

A Proposal

I argue that the issue of authorial intent in the Queerbaiting discourse can be somewhat resolved by considering that queer audiences picking up on queer themes in a piece of film or television can be deemed as enough authority over the meaning of said text, in accordance with Doty (1993)’s concept of queer authorship; and under the condition that their interpretations contend to Helgesson (2002)’s standard of providing sufficient proof within the text. Additionally, because they are discussed and accepted on a broad scale within the specific social organisation of fandom as theorised by Jenkins (2012), Queerbaiting debates are valid and legitimate collective readings, as opposed to idiosyncratic interpretations. This then evolves towards a conversation with creators carried out by the proximity that social media presently allows, and based on fandoms’ historical desire to influence production, which originated and boosted the Queerbaiting debate in the first place.

Furthermore, I posit that a case can be made against Queerbaiting when it comes to a finished isolated film with queer undertones, if there is no proof of the author’s intention to “bait” or explore queer audiences.

When it comes to franchises, though, in the current media landscape, it is almost impossible for creators to be unaware their work is being interpreted as queer, and that audiences are invested in a possible confirmation of their reading (and even demanding it). If they choose to capitalise on that investment by feeding into these readings (that, once again, they cannot deny they know of) in subsequent instalments, through either the same type of coding being used before or even stronger connotations, without ever making these meanings explicit, then that is Queerbaiting. This is true regardless of whether the author admits to it, due to the implications, primarily financial, that doing so would have.

Thus, I argue, that only in continued narratives, after the discussion is started by fans and reaches such magnitude it cannot be ignored by producers, can a work be undeniably accused of Queerbaiting, with no need for confirmation from its creator.

Queer readings are valid for isolated films, but the exploitive aspect present in Queerbaiting is very hard, and sometimes unfair, to establish in those cases. An exception can be made, though, for isolated films that explicitly promise queer content in their promotional paratexts, which is not present in the finished text or considerably less important than it was made out to be. A famous example of this is Disney’s 2017 Beauty and The Beast (Bill Condon).

Following a “moderate intentionalism” stance (Livingston 1998), in this proposed approach, authorial intent is still a defining feature of what makes something Queerbaiting, but the confirmation of this intent is no longer needed, since there are enough reasons to assume producers know exactly what they are doing, without them ever having to clearly state it.

Finally, I believe this approach also engages with Livingston (1998)’s notion of “artistic implicature” as the process of inferring a work’s implicit meaning through its explicit content, but also through “assumptions shared by artists and their audiences’’. These assumptions include “contextual beliefs’’ as well as “beliefs about the nature of the artist/interpreter interaction” (p.835). Throughout this article, I have laid out how both these dimensions guide Queerbaiting debates. The “contextual beliefs” include the reluctance by authors to admit to queer coding their works, due to possible homophobic backlash, together with Hollywood’s century-long tradition of keeping their queers implicit. The “beliefs about the nature of the artist/interpreter interaction” are based on queer audiences’ historical readiness to pick up on implicit meanings in texts, the power of fandom over the definition of a text’s meanings, and the impossibility of authors being unaware of queer readings (and the demand for their confirmation) based on present day’s use of technology and online social forums.

The Answer: Frozen, A Case Study

The Text

Frozen is a product of one of the biggest studios in the world, Walt Disney Studios, whose output is consumed virtually in every corner of the world, with an immeasurable cultural impact. Due to these massive international demands and heterogeneous audiences, Disney is a fitting example of the “access for all” policy (Elsaesser 2011) , making it also one of the companies most commonly accused of Queerbaiting. Within its long list of queer coded villains, its misleading promotion of queer characters, or its dubious narratives (Pixar’s Luca (Enrico Casarosa, 2021) for one), Frozen and its lead character Elsa stand out as the closest Disney has ever been to its first gay protagonist in a major feature film. Furthermore, Frozen is particularly relevant as one of Disney’s most popular outputs: Frozen (2013) was only dethroned as the highest grossing animated movie worldwide of all time by Frozen II (2019) (Rubin, 2020) and, in 2014, Time Magazine named Elsa the most influential fictional character of the year (D’addario, 2014).

Elsa is the heiress to the throne of the fictional Scandinavian kingdom of Arendelle. As the only person in the kingdom with powers, her ability to create and manipulate ice gets her into trouble when she accidentally freezes the nation over. Frozen (2013) and Frozen II (2019) tell Elsa’s journey towards controlling these abilities and, eventually, accepting and celebrating them. Hers is a story of difference, alienation, self-love and empowerment.

Most notably, queer readings of Frozen lean into Elsa’s powers as a metaphor for queerdom - her arc as an outsider with different abilities that people around her reject strongly mirrors the queer experience. Elsa’s parents attempt to stifle her powers from an early age, enclosing her so that she does not hurt her sister. Analysis on Frozen by Matte-Kaci (2019) and Farris (2020) parallel this confinement to the “closet” LGBT+ people find themselves in before they publicly announce their sexualities. Elsa is literally taught to “conceal, don’t feel, don’t let them know” (Let It Go, Anderson-Lopez and Lopez 2013), a mantra that has long been employed by the LGBT+ community as both a safeguard to keep themselves out of harm’s way but also as a legitimate mindset within the community, rooted in homophobia, as the only way to be successfully accepted into a cis-heterosexual society (DeAngelis 2001, 35). The process of coming to terms with one’s sexuality and effectively coming out of the closet is not at all different from what is depicted across both Frozen films. In the first instalment, Elsa can not hide any longer, her powers have become too strong now that she has grown up (much like one’s sexuality becomes unavoidable during puberty (Matte-Kaci 2019, 61)). In her isolated ice castle, she finds a safe place to be her true self, but just as long as no one can see her. Here, Elsa’s self-hatred - one of the ways mentioned to queer code a character - is prevalent.

It is only in the second film, where she truly gets to know her magic, its source, and history, and finds, in the Northuldra people, a community that not only accepts her but celebrates her special powers, that Elsa finally comes into her own. By the end of Frozen II (2019), Elsa has fully come out of isolation and escaped the entrapments of her title as Queen, which she abdicates in favour of her sister. Furthermore, in this film, Elsa makes her first friendship outside of her family circle, Honeymaren, a young Northuldra girl, with whom she shares an intimate scene by the fire (a setting with known romantic connotations in film). The reading of Honeymaren as more than a friend is also supported by the online movement #GiveElsaAGirlfriend, which emerged after the announcement of the sequel and will be explored ahead. Ambiguous buddy relationships, like Elsa and Honeymaren’s, that almost cross the line from platonic but never do, are yet another previously highlighted sign of queer coding.

It should be noted that Frozen is loosely based on Hans Christian Andersen’s 1844 tale Snow Queen. The title character, of which Elsa is an adaptation, was the villain of the origin story, with just as many queer undertones (Matte-Kaci 2019, 28). Villainy is also one of the codes brought up as a way to identify implicit queer characters in film, as well as Disney’s tradition of queer-coded villains. However, as a true sign of its times, Frozen subverts this trope, making the kingdom’s most feared character its protagonist and offering her understanding, empowerment, and heroism instead of punishment. Elsa cleverly “tows the line between being a powerful Disney villain and a feminine Disney princess” (Farris 2020, 36). Something similar happens in Luca, a story about sea monsters (keyword “monsters”) that seek comprehension from humans. The Disney of recent years rights its historical wrongs by giving its outwardly dangerous characters, feared by all, an empowerment arc of self-acceptance and celebration (versus fear) of difference.

Some of the stereotypes of the coded lesbian character that I previously indicate can still be found in Elsa - she is cold, as in a literal ice queen, neurotic, and closed off to the world and to (heterosexual) love. However, instead of being met with an untimely death, or otherwise punished, as typically happens to implicit lesbians on film, Elsa finds a community that celebrates her powers and gets a happy ending.

The Audience

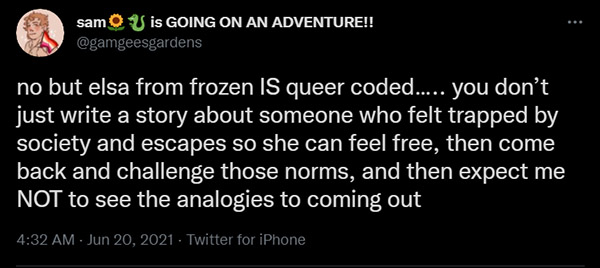

In a search through online platforms Twitter, Tumblr, and Youtube, it is clear that many fans link Elsa’s storyline to queer experiences (Figure 2). As such, despite Elsa’s sexuality not being explicit in the movies, she has become a queer icon nevertheless (Haasch, 2019).

Figure 2. Twitter user @gamgeesgardens’s post on Elsa being queer coded.

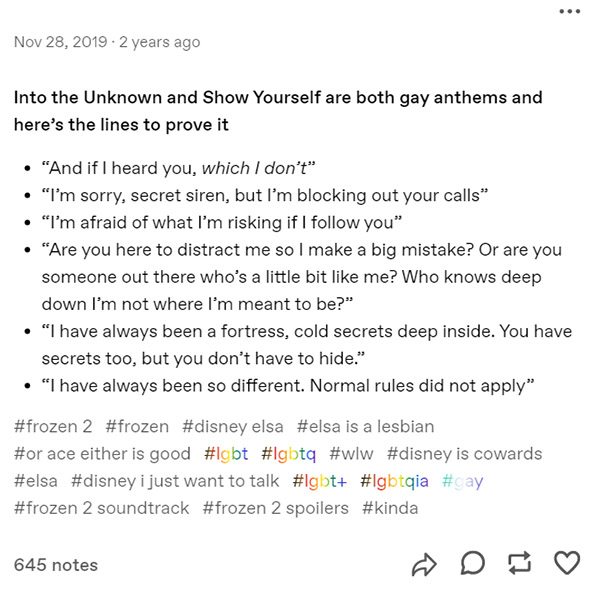

Songs from the franchise such as Let It Go (2013), Into the Unknown (2019) and Show Yourself (2019) were likewise received by the public as queer anthems. With their lyrics being adopted by queer viewers to convey their own experiences (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Tumblr post on the Frozen II (2019) songs Into The Unknown and Show Yourself.

Bordwell’s aforementioned theory of the spectator’s use of personal schemata “derived from everyday experience” (1985, 32) can be applied here in the way queer spectators have related Elsa’s struggle with her powers to the process of dealing with homosexual feelings.

Queer readings of Frozen gained even bigger traction with the spread of the hashtag #GiveElsaAGirlfriend on Twitter (Mettler 2016), echoing audiences’ longing for queer representation in film, especially in animated, Disney movies, due to the impact it could have particularly on children and their families (Hunt 2016). This hashtag is “not only the act of uttering a grievance but a way of trying to affect the product” (Nordin 2019, 30) - in this case, the Frozen sequel - thus reflecting queer audiences’ previously mentioned galvanising intentions.

When the trailer for Frozen II (2019) was released and Elsa did not seem to have been given a girlfriend, fans took to Twitter once again (Watercutter 2019).

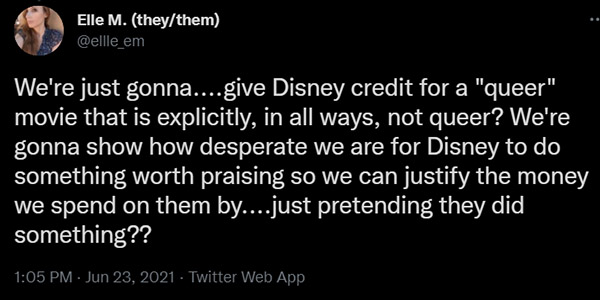

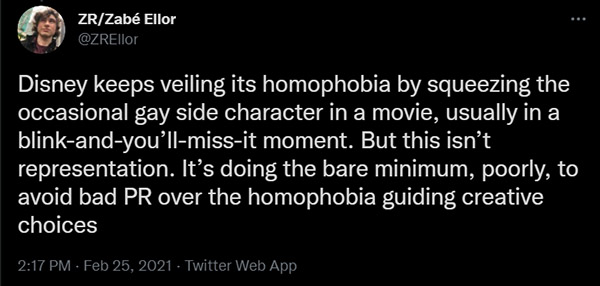

This discussion around the Frozen films, though, is part of a bigger ongoing debate about Disney’s handling of queer representation which reflects viewers’ activist objectives (Figures 4 and 5).

Figures 4 and 5. Viewers criticise Disney’s treatment of queer characters.

In the fanfiction repository Archive of Our Own, fans publish their own stories about Elsa, pairing her with Honeymaren or Anna. The most popular Elsa/Honeymaren fanfiction has over 57 thousand hits, meaning the number of times a work has been accessed, whereas the most famous Elsa/Anna story, dated back to 2016, amounted to 85 thousand.

The impact of Frozen’s queer readings was so massive even the popular comedy showcase Saturday Night Live (2020) included a sketch where Elsa and Anna talk about the former’s lack of romantic interest in the movies, referencing a “Twitter storm”, with Anna saying “we all know” and that she does not care what Disney says.

Authorship

A queer reading of the first Frozen film (2013) does not necessarily mean that the queer subtext was put there intentionally by its creators to speak directly to queer audiences.

However, as shown above, these queer readings became widespread knowledge and the production of Frozen II (2019) had to have been aware of them, making every choice in the film, namely the inclusion of Honeymaren’s character, conscientious of its queer double meaning and, therefore, intentionally queer coded.

Once this intentionality can no longer be denied, audiences have a good basis on which to accuse producers of Queerbaiting. Thus, whilst Frozen (2013) might have been accidentally queer, Frozen II (2019), which dives deeper into the thematics that audiences read as gay in the first installment, is perfectly aware of its implicit queer meanings. Therefore, it is fair to accuse producers of using them to “bait” queer audiences.

Bringing back Helgesson (2002)’s “two-dimensional analytical scheme of the meanings of “implicit”” (p. 47) (Figure 1), a Queerbaiting reading of the first Frozen film, I argue, could fit category 11 (“one of several plausible interpretations, acceptable to author but not intended”) and therefore not implicit. In this first film, there is no sufficient grounds in which to found an argument for queer subtext being written into the work intentionally with the purpose of attracting queer viewers in an exploitative fashion.

Like most creators accused of Queerbaiting, the question of intentionality and the prospect of explicit queer representation was cleverly dodged by writer and co-director of the films Jennifer Lee. In reaction to a possible queer storyline for Elsa in the sequel, Lee said that once the sequel had been released, “it [belonged] to the world”. Lee preferred to not police fans’ opinions and leave it “up to them” to create their own ideas about her films (Hunt 2016). This response is apparently open and accepting of queer readings without ever taking the risk to properly validate them, and thus not shunning conservative viewers and markets. This is often the case with works accused of Queerbaiting, and is exemplary of why the author’s word is not trustable enough in establishing their true intent. However, it is also proof that Lee is aware of queer readings of the first movie and, considering the sequel doubles down on the same subtext that these readings were based on, it is possible to form a strong argument for Queerbaiting in Frozen II (2019), regardless of authorial confirmation. It can, thus, be placed in category 10 of Helgesson (2002)’s scheme (Figure 1), as “one of several plausible interpretations, intended by author but not written” and, therefore, implicit.

Doty (1993)’s concept of queer authorship leads us to consider aspects beyond the themes and on-screen behaviours that viewers have interpreted as queer. Frozen had a particularly gay-friendly cast with Idina Menzel’s “status as an LGBT icon” (Matte-Kaci 2019, 36) and Jonathan Groff’s openly gay star persona favoring camp readings of the films. This “crossover appeal” (DeAngelis 2001, 4) of the films’ cast permits varied access points for gay viewers and makes queer readings more robust.

Furthermore, Queerbaiting discourses around Frozen happen in the context of fandom which gives these queer readings validity and power, based on their shared communal character. With the Queerbaiting debate extending to all of Disney and their recurrent exploitative treatment of queer audiences, this case study also exemplifies how it contributes to the “ongoing struggle [between audiences and producers] for possession of the text and for control over its meanings” (Jenkins 2012, 24). Queer fans who engage in the Queerbaiting debate are actively defining the standards these big media companies should be held to with the work they produce and how they choose to market it.

Conclusion

Research done on Queerbaiting in the past offered an important general background, introducing this concept to academic standards and encouraging more work to be done on the subject. In this article, I have broken down the different processes at play in Queerbaiting discourse, thus proposing a more systematic and detailed look into a relatively recent fan-born phenomenon.

Several conclusions can be drawn from the research I have conducted. Chiefly, I posited that Queerbaiting primarily combines three components - text, audiences and authorship -, each with their own problematics that intersect and affect one another.

In inspecting the component of the filmic text, I found that Queerbaiting is based in implicit meanings, more specifically coded queerness. To this end, I referred to different works concerning queer representation in film to draw out a list of queer coding’s five main clues - (performance of) gender, stereotyping, villainy, self-hatred and the buddy relationship.

Regarding the component of the audiences, I concluded that as spectators of film, queer viewers have distinct characteristics that influence the way they read and interpret film. Particularly, an historical predisposition towards the search and interpretation of implicit meanings in texts, the tendency to appropriate characters when explicit representation can not be found, and the uniquely passionate bond they form with them.

When it came to the third and most problematic component - authorship -, I proposed a model to establish intent based, amongst others, on Helgesson (2002)’s notion of implicit meaning and Livingston (1998)’s notion of artistic implicature, both within a moderate intentionalism framework. Thus, I argued that, safe for exceptions that I specified, single films cannot be accused of Queerbaiting in a well-founded way. Sequels, and other continuations of a work, however, produced after queer readings of the first installment surge, and that capitilase on this audience engagement by maintaining coded queerness in their text without ever offering confimartion, can be accused of Queerbaiting, wether or not the author admits to doing so.

A secondary observation made throughout this article is that Queerbaiting has roots in a long tradition of ambiguity in Hollywood storytelling, with the intent to maintain varied access points, in order to ensure mass engagement (Elsaesser 2011, 248). Queer fans that started the Queerbaiting debate are, then, a product of a long history of spectators that have been conditioned to search for implicit queer meanings in film and television. They are also, however, the first generation of media consumers to grow up with a (limited) number of explicit queer representation on screen, which has increased their standards and decreased their tolerance for implicit queerness. They are likewise the first generation to have the tool of social media bring them significantly closer to the people who have historically held the power of decision over mainstream culture.

Finally, by applying the concepts and theories compiled throughout this article to the case study of the Frozen franchise (2013, 2019), I have suggested a workable and adaptable model to establish whether or not a particular film is an example of Queerbaiting, by breaking it down into the aforementioned three components, and examining them separately and systematically.

Future research done on this topic can consider aspects of the phenomenon that have been left underdeveloped here, such as a more detailed look into socioeconomic factors that lead media companies to practice Queerbaiting, or the state of explicit queer representation in Hollywood in the sense of if and how it can influence said practice.

Final Notes

1This article is an adaptation of a Master’s Dissertation of the same title.

2Captain America: The First Avenger (Joe Johnston, 2011), Captain America: The Winter Soldier (Anthony Russo, Joe Russo, 2014), Captain America: Civil War (Anthony Russo, Joe Russo, 2016).

3Star Wars: The Force Awakens (J. J. Abrams, 2015), Star Wars: The Last Jedi (Rian Johnson, 2017), Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker (J. J. Abrams, 2019).

Bibliography

1934. A Code to Govern the Making of Motion and Talking Pictures: the Reasons Supporting It and the Resolution for Uniform Interpretation. [Pamphlet] Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Core Collection Pamphlets.

Andersen, Hans Christian. 1844. The Snow Queen. In: New Fairy Tales. First Volume. Second Collection. Denmark.

Barthes, Roland. 1967. The Death of the Author. Aspen, (5-6).

Benshoff, Harry and Sean Griffin. 2005. Queer images: A History of Gay and Lesbian Film in America. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield.

Berliner, Todd. 2017. Hollywood Aesthetic: Pleasure In American Cinema. New York, USA: Oxford University Press.

Bordwell, David. 1985. Narration In The Fiction Film. Routledge.

Bordwell, David. 1989. Making meaning : inference and rhetoric in the interpretation of cinema. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard Univ. Press.

Brennan, Joseph. 2019. Queerbaiting and Fandom : Teasing Fans Through Homoerotic Possibilities. Iowa City: University Of Iowa Press.

Brooke, Michael. n.d. BFI Screenonline: The Hays Code. [online] Screenonline.org.uk. Available at: <http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/592022/> [Accessed 5 June 2021].

Butler, Judith. 1988. Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory. Theatre Journal, 40(4), p.519.

China Daily, 2017. China has become important market for Walt Disney International. [online] Available at: <https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2017-07/14/content_30114149.htm> [Accessed 9 September 2021].

D’addario, Daniel. 2014. These are the 15 Most Influential Fictional Characters of 2014. [online] Time. Available at: <https://time.com/3612615/influential-characters-2014/> [Accessed 9 September 2021].

DeAngelis, Michael. 2001. Gay Fandom and Crossover Stardom. Duke University Press Books.

Doty, Alexander. 1993. Making Things Perfectly Queer: Interpreting Mass Culture. Minneapolis u.a.: Univ. of Minnesota Press.

Dyer, Richard. 2012. The Culture of Queers. London: Routledge, pp.90-115.

Elsaesser, Thomas. 2011. James Cameron’s Avatar: access for all. New Review of Film and Television Studies, 9(3), pp.247-264.

Farris, Molly. 2020. Into The Unknown: A Queer Analysis Of The Metaphors In Disney’s Frozen Franchise. Master of Arts in Communication Studies. University of North Carolina.

Haasch, Palmer. 2019. Frozen 2’s ‘Show Yourself’ reads like the queer anthem fans want. Polygon, [online] Available at: <https://www.polygon.com/2019/11/27/20985979/frozen-2-elsa-show-yourself-queer-anthem-giveelsaagirlfriend-gay-lbgqt-representation-disney?utm_campaign=polygon&utm_content=chorus&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter> [Accessed 13 September 2021].

Helgesson, Gert. 2002. What Is Implicit?. Crítica: Revista Hispanoamericana de Filosofía, 34(100), pp.33-54.

Hunt, Elle. 2016. Frozen fans urge Disney to give Elsa a girlfriend in sequel. The Guardian, [online] Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/may/03/frozen-fans-urge-disney-to-give-elsa-girlfriend-lgbt> [Accessed 13 September 2021].

Jenkins, Henry. 2012. Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture. 2nd ed. London: Taylor & Francis Group.

Livingston, Paisley. 1998. Intentionalism in Aesthetics. New Literary History, 29(4), pp.831-846.

Matte-Kaci, Leila. 2019. Thawing The Snow Queer: Queer Readings Of Frozen’s Elsa. Master of Arts in Children’s Literature. University Of British Columbia.

Mettler, Katie. 2016. #GiveElsaAGirlfriend in Frozen 2 asks new Twitter campaign. The Washington Post, [online] Available at: <https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2016/05/03/giveelsaagirlfriend-in-frozen-2-asks-new-twitter-campaign/> [Accessed 14 September 2021].

Mira, Alberto. 2011. Nuevas perspectivas, nuevas cartografías: de los Gay Studies a la teoría Queer. Secuencias. Revista de historia del cine.

Ng, Eve. 2017. Between text, paratext, and context: Queerbaiting and the contemporary media landscape. Transformative Works and Cultures, 24.

Nordin, Emma. 2019. Queerbaiting 2.0 From Denying Your Queers To Pretending You Have Them. In: J. Brennan, ed., Queerbaiting and Fandom: Teasing Fans Through Homoerotic Possibilities. Iowa City: University Of Iowa Press.

Rubin, Rebecca. 2020. ‘Frozen 2’ Becomes Highest-Grossing Animated Movie Ever - Variety. [online] Variety.com. Available at: <https://variety.com/2020/film/box-office/frozen-2-biggest-animated-movie-ever-disney-box-office-1203456758/> [Accessed 13 September 2021].

Russo, Vito. 1987. The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies. New York: Harper & Row.

Filmography

Aladdin. 1992. Directed by R. Clements and J. Musker. United States: Walt Disney Pictures.

All About Eve. 1950. Directed by J. L. Mankiewicz. United States: 20th Century Fox.

Avatar. 2009. Directed by J. Cameron. United States: 20th Century Fox.

Beauty and the Beast. 2017. Directed by B. Condon. United States: Walt Disney Pictures.

Brokeback Mountain. 2005. Directed by A. Lee. United States: River Road Entertainment.

Caged. 1950. Directed by J. Cromwell. United States: Warner Bros.

Captain America: Civil War. 2016. Directed by A. Russo and J. Russo. United States: Marvel Studios.

Captain America: The First Avenger. 2011. Directed by J. Johnston. United States: Marvel Studios.

Captain America: The Winter Soldier. 2014. Directed by A. Russo and J. Russo. United States: Marvel Studios.

Cat On A Hot Tin Roof. 1958. Directed by R. Brooks. United States: Avon Productions.

Children’s Hour. 1961. Directed by W. Wyler. United States: United Artists.

Dead Reckoning. 1947. Directed by J. Cromwell. United States: Columbia Pictures.

Frozen II. 2019. Directed by C. Buck and J. Lee. United States: Walt Disney Pictures.

Frozen. 2013. Directed by C. Buck and J. Lee. United States: Walt Disney Pictures.

Gilda. 1946. Directed by C. Vidor. United States: Columbia Pictures.

Hercules. 1997. Directed by R. Clements and J. Musker. United States: Walt Disney Pictures.

Kiss Of Death. 1947. Directed by H. Hathaway. United States: 20th Century Fox.

Laura. 1944. Directed by O. Preminger. United States: 20th Century Fox.

Luca. 2021. Directed by E. Casarosa. United States: Walt Disney Pictures.

Ocean’s 8. 2018. Directed by G. Ross. United States: Warner Bros.

Onward. 2020. Directed by D. Scanlon. United States: Walt Disney Pictures.

Pitch Perfect. 2012. Directed by J. Moore. United States: Gold Circle Films.

Pocahontas. 1995. Directed by M. Gabriel and E. Goldberg. United States: Walt Disney Pictures.

Psycho. 1960. Directed by A. Hitchcock. United States: Shamley Productions.

Rebecca. 1940. Directed by A. Hitchcock. United States: Selznick International Pictures.

Rebel Without A Cause. 1955. Directed by N. Ray. United States: Warner Bros.

Rope. 1948. Directed by A. Hitchcock. United States: Transatlantic Pictures.

Star Wars: The Force Awakens. 2015. Directed by J. J. Abrams. United States: Lucasfilm Ltd.

Star Wars: The Last Jedi. 2017. Directed by R. Johnson. United States: Lucasfilm Ltd.

Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker. 2019. Directed by J. J. Abrams. United States: Lucasfilm Ltd.

Strangers on a Train. 1951. Directed by A. Hitchcock. United States: Transatlantic Pictures.

The Big Sleep. 1946. Directed by H. Hawks. United States: 20th Century Fox.

The Lion King. 1994. Directed by R. Minkoff and R. Allers. United States: Walt Disney Pictures.

The Little Mermaid. 1989. Directed by R. Clements and J. Musker. United States: Walt Disney Pictures.

The Maltese Falcon. 2021. Directed by J. Huston. United States: Warner Bros.

Young Man With A Horn. 1950. Directed by M. Curtiz. United States: Warner Bros.

Videography

Saturday Night Live, 2020. Frozen 2 - SNL. [video] Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tKvDw6cfR3c> [Accessed 15 September 2021].

Social Media Posts

2019. This is what we hope every one of you will get to experience at some point (soon!). [Twitter] Available at: <https://twitter.com/lezhangoutpod/status/1199714496815783936> [Accessed 14 September 2021].

2020. Disney: “We are PROUD to announce a LGBT character in our next movie!”. [Twitter] Available at: <https://twitter.com/Saberspark/status/1231379949937971201> [Accessed 14 September 2021].

Ellor, Zabé. 2021. Disney keeps veiling its homophobia by squeezing the occasional gay side character in a movie.... [Twitter] Available at: <https://twitter.com/ZREllor/status/1364942495495434242> [Accessed 14 September 2021].

Maruska, Elle. 2021. We’re just gonna....give Disney credit for a “queer” movie that is explicitly, in all ways, not queer?. [Twitter] Available at: <https://twitter.com/ellle_em/status/1407671162990206976> [Accessed 14 September 2021].

Margolin, Jamie. 2019. THREAD ABOUT LGBT MEDIA REPRESENTATION. [Twitter] Available at: <https://twitter.com/jamie_margolin/status/1154890611020816385?lang=en> [Accessed 14 September 2021].

hot leaf content. 2019. “Show Yourself” brought me to tears in the theater. [Tumblr] Available at: <https://space0utlaw.tumblr.com/post/189968290366/show-yourself-brought-me-to-tears-in-the-theater> [Accessed 14 September 2021].

This blog is dead. 2019. Into the Unknown and Show Yourself are both gay anthems and here’s the lines to prove it. [Tumblr] Available at: <https://moth-sword.tumblr.com/post/189351291793/into-the-unknown-and-show-yourself-are-both-gay> [Accessed 14 September 2021].

Music

Anderson-Lopez, Kristen and Robert Lopez. 2013. Let It Go. Walt Disney Records.

Anderson-Lopez, Kristen and Robert Lopez. 2019. Into The Unknown. Walt Disney Records.

Anderson-Lopez, Kristen and Robert Lopez. 2019. Show Yourself. Walt Disney Records.