Abstract

FilmEU is an alliance including Lusófona University, Portugal, Baltic Film and Media School, Estonia, LUCA, Belgium and IADT, Ireland. Together they are working to create a collaborative University of Film and Media Arts. This paper aims to elucidate their pilot project which consisted of a year-long Challenge Module designed for 2nd year film and media BA students in the consortium and represents the first test implementation of the Samsara pedagogical framework. Students came together to create mini-series from concept development to postproduction. This project asked students to incorporate and consider a societal challenge in their work. The first challenge topic launched by FilmEU concerned “Sexuality, Gender and Censorship”. By developing and producing a pilot for a short-form series or other media art projects in collaborative teams drawn from four of the Alliance institutions, the students posited their stories within a larger social sphere. This paper will document the process, challenges, aims and objectives of the first pilot project from the FilmEU alliance.

Keywords: Collaborative Filmmaking, Teaching Model, Social Challenge, Samsara, FilmEU

Introduction

This paper documents the implementation of the first pilot project of FilmEU. FilmEU is a European Alliance including Lusófona University, Portugal, Baltic Film and Media School, Estonia, LUCA, Belgium and IADT, Ireland. Together they implemented their pilot project where students from the four institutions engaged with a societal challenge and worked with their peers across borders both digitally and physically. This project was the first implementation of FilmEU’s Samsara Pedagogical Framework which will be the focus of theis paper, it was also a testing ground logistically for implementing a transnational module at undergraduate level. This paper documents the objectives of FilmEU, the conceptual framework of this project, and the methodologies used. It will go on to explain the reason behind using societal challenges and the integration of Challenge Based Learning into these practical projects. This paper documents the layout and outputs that were created within the 2021-2022 timeframe. Finally, it will briefly address the importance of mobilities to the FilmEU project and the impact that Covid-19 had on the delivery of this pilot challenge.

The first pilot challenge was concerned with “Sexuality, Gender and Censorship”. Participating students were chosen from second year and final year undergraduate BA courses from the Alliance. The students all worked together to create project concepts, pitches, scripts, finished productions and supplementary transmedia material. The transmedia outputs themselves (such as; games, Instagram accounts, alternative storylines from characters or world perspectives, blog) will not be addressed in this particular paper as at the time of writing the transmedia component has not been completed. Three of the successfully chosen mini-series are now in various stages of post-production and one project which was delayed due to Covid-19 is being filmed at the same time as writing this journal. The implications of Covid-19 and its effect on such a complicated transnational project will also be briefly examined. All four projects (web series, transmedia outputs and student presentations) will be presented publicly in July 2022 and the second FilmEU summit in IADT, Ireland.

FilmEU Objectives

At the Gothenburg Summit in 2017 European leaders announced that they wanted to strengthen the competitive nature of European higher education as well as integrating mobilities and trans national educational approaches by creating Alliances of universities in different disciplines. Encouraging a “bottom up” approach that, as described by the Council Conclusions on the European Universities achieves;

the ambitious vision of an innovative, globally competitive and attractive European Education Area and European Research Area, in full synergy with the European Higher Education Area, by helping to boost the excellence dimension of higher education, research and innovation, while promoting gender equality, inclusiveness, and equity, allowing for seamless and ambitious transnational cooperation between higher education institutions in Europe, and inspiring the transformation of higher education (Europa.eu)

One of the first priorities of the Alliance was to research and outline their core pedagogical and ethical approaches to Film and Media Arts education. The following FIVE principles are core to the success and sustainment of the FilmEU pedagogical framework:

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Equality and Equity

- Mobility

- Sustainability

- Technological Mediation

(FilmEU, 2021)

This paper documents the first pilot project termed “Challenge Pilot” which asks students to focus and produce artifacts that are not just sources of entertainment but go further and are also representative of the principles of this pedagogical framework. Some of this is within logistical implications of the project itself including Mobilities and Technological Mediation. However, the other pillars of Diversity and Inclusion and Equality and Equity are more complicated and are addressed by the “challenge” itself. The next section will articulate what a challenge is and why it is important to transcend the filmmaking process and engage students with ethical and conceptual approaches to their art.

Conceptual Framework

The idea of Challenge-Based Learning (CBL) (Johnson, Smith, Smythe, Varon, 2009) is not an original one, but it is an important one. It engages students with the wider world and asks them to think of the reasons, ethics and stories inspiring their creative process. It asks them to to situate their work within a larger social sphere and to tell stories with purpose. Stories are how we see ourselves and how we comprehend the world around us (Andrews, 2010).

Challenge based learning as a constructionist approach is often attributed to Papert (1972), but can be seen in more recent applications by looking at tech giants such as Apple in their Apple Classroom for Tomorrow Initiative which was aimed at secondary level education, and has increased the visibility of CBL within the entire educational field.

FilmEU will annually choose a challenge that calls on students to consider a societal challenge throughout their work, whether it be fiction, documentary, transmedia, multimedia or indeed, in the films and media they consume. CBL has been incorporated into FilmEU’s Samsara Pedagogical Framework (see below) and when choosing a challenge the following considerations have been outlined, it should:

- have a social impact

- be explicitly linked to the development of key artistic skills and knowledge

- be significant and create a sense of urgency and relevance in learners and participants

- be broad enough in scope to provide multiple entry points for student growth & exploration and allow for an inclusive space for a great diversity of students who come from cultures in various stages of social transformation

- be curated by partner institutions: expertise and resources to develop and execute modules, activities and events

(FilmEU, 2021)

CBL and this pilot aim to engage students in addressing and perhaps even help solving urgent, real-world problems in a collaborative, multidisciplinary and practical way. Students should seek not only to critically evaluate the social impact and social implications of their creative work, but also to explore how creative work can actively and positively transform society. Students simultaneously explore a Challenge Topic while making a film/media art challenge-project.

Coupling purpose and production is a formidable pedagogical tool for media arts education because it provides opportunities to link meaning and making, a difficult concept for students to master. This parallel work constantly reminds students how content and form both contribute to meaning and encourages them to consider the different and important contributions of thinking, doing, and making in their work. This act of researching and making in tandem is one espoused by theorists such as Nelson (2013), Sullivan (2005, 2014) and Barrett and Bolt (2014), when describing ‘Praxis’ or having research inform practice, and practice cyclically informing research. The idea of praxis is often attributed to post graduate research and PhD and doctoral studies. As such, bringing in this concept at an undergraduate level in a simplified way also creates pathways that may lead students to contemplate further research.

Samsara Pedagogical Framework

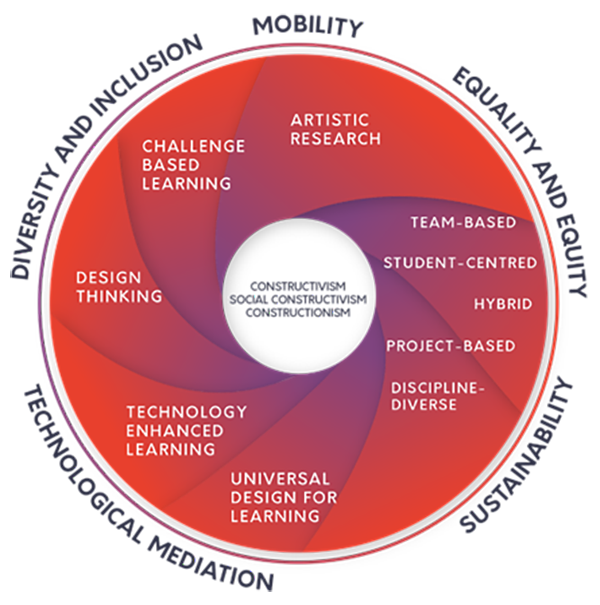

Figure 1 - FilmEU Samsara Pedagogical Framework (2021.12.01)

The Samsara Framework (FilmEU, 2021) outlines approaches for teaching practiced based and creative topics including Film and Media Arts. Emphasis is put on learning through doing and it has emerged from a plethora of pedagogical approaches. Building on Constructivism (John Dewey 1934, 1938, Jerome Bruner, 1960) which espouses learning from experience, Social Constructivism (Vygotsky 1978) that promotes learning from collaboration and encounters with others and Constructionism (Papert, S. & Harel, I., 1991) which acknowledges creative outputs as sources of knowledge. The Samsara approach is placing the creative process in the centre of its pedagogical approach.

Surrounding them are the methodological approaches that could be taken in order to achieve this aim including CBL, Student Centred, Project Based and Technological Enhanced Learning, and Design Thinking all of which were utilised throughout this pilot project. Surrounding the Methodologies is the FilmEU objectives which are the pillars of the FilmEU project (see FilmEU objectives)

One focus of the Samsara Framework that was not dealt with directly in this pilot is that of Sustainability. Filmmaking along with many industries is at a time of change, embracing more sustainable practices this will change how we deal with every interaction in both filmmaking and in our work within film schools and universities. Using sustainability not just as a work ethos but as a challenge, will enable the students to interrogate it both as a methodology and as a conceptual framework. Sustainability will be incorporated in subsequent challenges and will be embraced as an essential part of all FilmEU endeavours.

In the following section the challenge for 2021/2022 “Sexuality, Gender and Censorship” will be expanded on.

Challenge Concept; Sexuality, Gender and Censorship

Gender is not something that one is, it is something one does, an act...a doing rather than a being.- (Butler, 1999, 42)

The challenge was purposely broad to allow for students to decide which part of the topic appeals to them. However, it was narrow enough to “challenge’ the students to engage and create within the confines of the societal theme. It facilitated coming at the topic from both a conceptual and technological approach. This section lays out a brief “state of the art” of the Challenge Topic and explores both the historical context of the theme as well as offering modern interpretations of the subject which were offered to students as a ‘jumping off point’ for discussions.

Figure 2 - Skam (Julie Andem, 2015 - 2017)

Figure 3 - Skam (Julie Andem, 2015 - 2017)

Shame, sexuality, gender, individual freedom, are topics that never cease to engage media audiences. Nevertheless, across the world, age classifications for media content are far from unified and can lead to bizarre situations, such as the one experienced by filmmaker Ken Loach, upon the release of his film Sweet Sixteen, in 2002. As stated in The Guardian newspaper, Ken Loach suggested that British teenagers should ignore the 18-certificate rating for this movie. Along with his screenwriter Paul Laverty, the veteran filmmaker dismissed the British Board of Film Classification, rating it as unfair and as sending a worrying message.

Can one survive professionally in the media without mainstream attention and the moral judgement that comes with it? Images, words, everything is up for grabs and subject to scrutinization under specific principles, and if the Internet can be a seemingly endless outlet for underground expression, young practitioners need to realise, sooner rather than later, that institutional funding will also obey certain moral codes, and that specific content can be censored at the very stage of fundraising.

Starting in 2015, the Norwegian series Skam hit the spot with young audiences worldwide. For many viewers it simply started as something flitted across Tumblr dashboards or Twitter feeds. As the Den of Geek explains, Skam, which translates to shame, in English, is a Norwegian teen drama that took the internet by storm, despite the fact that there are no legal English language-subtitled streams available (mostly it seems, due to music rights) and there was no official marketing push.

Since the birth of the moving image in the late 19th Century, the representation of sexuality and gender has attracted both viewers and animosity, freedom of expression and censorship, with silent film already embodying a profusion of daring renditions.

The representation of sexuality and gender in film has been a story of constant advancement and regress, more or less in line with societal cycles, local or global shifts towards conservatism or progressivism, and the continually shifting frontiers of the obscene. The implementation of the Hays Code, in 1934, had an impact that lasted decades, not solely in its country of origin, the USA, but internationally, across the western world. And in Europe, dictatorships and strict moral perspectives led to the establishment of systems of censorship on film production and distribution which, in several countries, lasted until the 1970s and sometimes beyond. But, resolutely, across most of the western world, film censorship progressively gave way to classification according to the content and the age group of the audience. An exceptional example of a filmmaker forbidding that an audience watches one of his films is Stanley Kubrick, with A Clockwork Orange, which he banned from the UK after audiences displayed anti-social behaviour following its screening.

Figure 4 - A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971)

The late 20th century witnessed a wave of international sexual revolution which, at its zenith, promised the utopia of both sexual freedom and gender equality. Filmmakers had the nerve to dare sexually once again, with new aesthetic and moral values that portrayed society and sexuality through a lens that felt real and provocative, with no intention of being consensual and conforming to conservative values.

Figure 5 - Midnight Cowboy (John Schlesinger, 1969)

Figure 6 - Blue Velvet (David Lynch, 1986)

Twenty years into the 21st century, values and notions concerning gender and sexuality still differ sharply across western democracies and the international movement “Me Too”, in particular, has put the spotlight on how far we still are from gender equality and sexual freedom. LGBTQ+ groups have to be fighting once again for basic rights that only recently could be taken for granted. Gender and personal freedom is a key social theme and filmmakers’ lenses are absolutely necessary to steer the debate, provoke and ultimately transform views of what is sometimes perceived as the other in a fellow human.

Figure 7 - Boys Don’t Cry (Kimberly Peirce, 1999)

Figure 8 - Blue is the Warmest Colour (Abdellatif Kechiche, 2013)

In the field of artistic film creation, freedom also seems elusive when film works are currently censored or severely criticised for transgressing the limits of what is considered decent or politically correct. Regardless, throughout the history of film, filmmakers from across the world have left us a legacy that ranges from the most sophisticated to the crudest, from the most obvious and sometimes violent to the most subtle and delicate. To delve into the proposed theme will enable us to consider key aesthetic and political concepts and how these can be expressed today, using film, across a multitude of transmedia platforms, raising important questions and validating how artististic expression promotes debate and manifests its relevance in the consolidation of democratic values.

It is indisputable the notion that media products can be agents of social transformation in and beyond democracy. It is vital to empower new generations of filmmakers with the right skills to fulfil their creative potential, whilst giving them a solid platform to enact their values and a springboard from which they can create social impact. Departing from the fact that practical experience is unteachable, the lecturers in this programme will always reach for innovative methodologies to undertake the task of working around this gap, always assuming that to teach creatively is to teach critically.

The ‘Challenge’ embodies the ‘what’ question that is often talked about when teaching film production now? The following section will detail the ‘why?’, the aims and objectives of students engaging with the module and what we hope they will gain from this process.

Challenge Aims and Objectives

The aims of the challenge itself differs from that of the FilmEU alliance as a whole, in that it was more specific to this particular project brief and that in it, we were outlining what we wanted of the students and therefore we could be more focused and detailed about what was expected and what could be achieved. In the following list of aims and objectives the goals of FilmEU are apparent alongside practical steps in how to deliver and undertake the module itself;

Aims:

- To empower students in the understanding of film and media history.

- To give students comprehensive tools to discern and discuss the ethics of gender, sexual representation, classification and censorship at an international level.

- The establishment of solid competences in digital film, providing students with key skills for contemporary film and media filmmaking.

- To train students to work in a team-based environment.

Objectives:

- The expansion and application of an interdisciplinary training program focusing on transmedia, providing students with the right theoretical and technical skills to succeed as transmedia creators.

- To promote a comprehensive mapping of contemporary media outlets.

- Students will learn how to discover and research differences and similarities between people with different cultural backgrounds, becoming proficient in understanding international projects.

- Any group which, at the start, includes individuals with different levels theoretical and technical know-how should, at the end, express a more balanced level of proficiency.

- The blossoming of co-production enterprises between all institutions involved in the FilmEU Alliance.

- To create a solid platform for discussion and consolidation on the topic of citizenship and democracy when applied to an author’s social impact.

The above aims and objectives allow for what would be expected in many practical modules that deal with film or media production. However, peppered through those aims and objectives are elements of the core values of FilmEU. Having students engage with topics that reflect the dynamic and complicated world they live in, giving them space to investigate their own world view and above all else giving them the means and the platform to produce a web series that reflects that interrogation and allows their voices to be heard.

Barr & Tagg (1995) assert that the emphasis of learning within the educational sphere has moved in the past few decades from the teacher to the student. Or as an adage that King (1993) points out; “from the sage on the stage, to the guide on the side”. These projects are student led and student focused, they have the capacity to create and then they are helped with skills and advice that would allow them to complete each stage of this process.

Pilot Challenge

Figure 9 - Students and teachers from all institutions meeting on 2021-10-29

In the 2021/2022 academic year FilmEU implemented a Pilot Challenge to test the Samsara Pedagogical Framework. This was built upon an existing Lusófona University, Portugal (ULHT) module that teaches transversal web series that has been expanded to encompass challenge-based methodologies and to include an international cohort of students.

During the first semester, all students met online for Masterclasses that would immerse them in the topic. They had the following four masterclasses that asked them to engage with the topics from different perspectives

- Érica Faleiro Rodrigues

- Rory O’Neill and Conor Horgan

- Elen Lotman

- Wim Forceville

Figure 10 - Q&A attended by teachers and students on 2021-11-26 With Rory O´Neill - Panty Bliss - (pictured) and Conor Horgan, protagonist and director from The Queen of Ireland.

Students and teachers watched and discussed both the film and LGBTQ+ civil rights.

These masterclasses worked both as a tool for exploration but it had added value as the students began to understand the lens in which their fellow students saw the world. They could learn from filmmakers who came before them and ask questions about what it is to create films that address topics that effect people’s lives. These stories are often emotionally charged and important for both the storyteller and the audience to comprehend. By researching the topic in depth, the students can reach audiences on both on a personal, narrative and emotional level and therefore they can address the affective register. As Plantinga (2018, 39) states:

“(a)ffect and emotion are the key to the rhetorical nature of storytelling. They not only enable our full understanding of the story but also provide an incentive to follow the story intently - to become and remain immersed and absorbed”.

The students at the same time as attending virtual masterclasses with their fellow students were working in their own campuses conceptualising and writing their own web series, either in writing teams of three students or in some cases, all students were tasked with creating a concept and original draft. Either way, the students then voted to see which projects they would like to collaborate on and put forth to the Team Building Week in the second semester.

At Team Building Week teams of two to three students presented a Team Pitch to all the students and staff working on the Pilot. Each idea was interrogated and at the end of the session four projects were chosen. One project from each member of the Alliance. After the four chosen projects had emerged international crews were put together and the rest of the week was spent in pre-production. This was the first time the students had been working on the same project with their international colleagues. Throughout the week they reimagined scripts, discussed production design, cinematography, soundscapes and pacing. They became the film crews that would be needed to realise the major outputs of this Pilot Project; the web series.

Figure 11 – Birth of Helena (Hana Mohamed, 2022).

Web Series

The projects pitched had fascinating insights into not only the topic but the Technological Mediation that students wanted to engage with. There were stories that dealt with religion, family dynamics, ageing, relationships, parental challenges and LGBTQI+ narratives. Students pitched both traditional formats, Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality. This pitch showcased the power of storytelling and the rich tapestry that using CBL can create.

The following projects were chosen and created as the premiere pilot projects for FilmEU Challenge 2021/2022;

- Live and Let Live

- The Birth of Helena

- Reflections

- High Entropy

Projects and scripts presented at the Team Building Week were at various levels of completion. Some were fully formed and were ready for pre-production, while, others, gave the opportunity for collaboration much earlier within the creative process. This was a learning experience for staff and students alike. A major part of this pilot project is to begin to work together as an Alliance and as the four partner institutions often have different approaches to both modules and the creative process, the pitch panel was an opportunity to understand each other’s methodologies and to begin discussions on harmonisation going forward.

One of the important pillars from this project however, for both Team Building Week and the productions themselves was mobilities for students and staff, which allowed for all the collaborations needed. This will be discussed in the next section.

Mobilities

As previously outlined mobilities - which is the movement of students and staff both physically to different member states of the Alliance and digitally by working together online is an important pillar for both the FilmEU objectives and the Samsara Pedagogical Framework. Outside of FilmEU it is also a main priority for the EU commissions vision for University Alliances, and as such is integral to all European Alliances.

Digital mobilities occurred when students came together online using Microsoft Teams and Zoom to have classes and workshops that addressed the Challenge Topic. They were also invaluable for collaboration in pre and post production. Physical mobilities occurred three times across the project during; Team Building Week, the production of the web series in four countries and the presentation of projects at the FilmEU summit.

Creating mobilities at doctoral research level has been highlighted by ELIA’s Vienna Declaration on Doctoral Research in the Arts which asserts that mobilities are important in order to broaden the scope of the artistic work being created as well as embedding an international scope at all stages of the creative process. This is reflected within the vision of this pilot project which wants students to engage in a wider community and build a European cinema that is multifaceted and informed. However, it is embedding this transnational approach in early filmmakers during their undergraduate study.

Mobilities are important not just for the students and the institutions but for the creation of knowledge by providing a space for collaboration. It becomes a place for pushing the boundaries of what is possible. For filmmakers it allows them to see through a different lens, and to articulate new stories and perspectives. Within collaboration various frameworks of knowledge can exist including motivations, judgements and various creative outlooks (O’Toole, 2019, Shanahan et al., 2016), This collaboration may well be the most important output of this Challenge Project.

Figure 12 – Live and Let Live (Jaka Prosenik 2022).

Implications of Covid-19

An impacting factor for this project as well as everything within the years 2021-2022 was Covid-19 and the various subsequent Covid variants. For the FilmEU project as a whole which started during the height of Covid the digital communication used solidified the importance of Technical Mediation and new workflows for collaboration not just on this pilot project but for all aspects of the Alliance. At that time, in late 2020 there was no alternative to digital communication as lockdown had removed the possibility of in person collaboration not only internationally but within each institution as well.

Covid-19 delayed many meetings and deadlines during this pilot. During the Team Building Weeks special covid protocol were implemented including antigen testing and wearing masks. The final shoot for the web series was rescheduled after students contacted Covid 19 in Ireland, leading the original shoot week to instead be an isolation week. Overall, Covid has caused many hurdles and inconveniences throughout this project. However, the pilot challenge continued despite these complications and as an Alliance it is important to note that many efficient workflows and communication tools were implemented to achieve our aims and objectives. During this historic time when we all learnt how to isolate mobilities such as this one show how important it is to come together.

Conclusion

The premier Challenge project Sexuality, Gender and Censorship” gave a platform for four web series to emerge and be showcased. It became a space for debate and discussion for various issues that arose from such a personal and often hard to talk about topic. It allowed students to engage with cinematic history and contemporary filmmakers. Peer to peer learning, mobilities and working with international crews was all facilitated. From an institutional perspective it allowed for the testing of the Samsara Pedagogical Framework, for learning from the logistical implementation of such a large project and showcased successes and problem areas to be addressed in future iterations. This is the first Challenge and future iterations may be very different in both methodological, creative and conceptual approaches, however, learning from the pilot and disseminating the work flow and decision making process is vital for its success and future success.

Notas Finais

1Dr Deirdre O’Toole

Bibliography

Andrews, Molly. “Beyond narrative.” Beyond narrative coherence (2010): 147-166.

APPLE Apple Classrooms of Tomorrow – Today Whitepaper. Access at: https://www.apple.com/ca/education/docs/Apple-ACOT2Whitepaper.pdf (2008).Last accessed (12-05-22)

APPLE Challenge Based Learning: A classroom guide. Access at: https://images.apple.com/education/docs/CBL_Classroom_Guide_Jan_2011.pdf (2010). Last Accessed (31-12-21)

Barrett, Estelle, and Barbara Bolt, eds. Practice as research: Approaches to creative arts enquiry. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014.

Bruner, Jerome S. The process of education. Harvard university press, 2009.

Butler, Judith. Gender trouble. routledge, 2002.

Dewey, John. “The supreme intellectual obligation.” Science 79, no. 2046 (1934): 240-243.

Dewey, John, and Is Experiential Learning Authentic. “Experiential learning.” New Jersey: Pentice Hall (1938).

Europe Univesities Initiative, https://education.ec.europa.eu/education-levels/higher-education/european-universities-initiative, Last access on 22 Apr 2022)

Harel, Idit Ed, and Seymour Ed Papert. Constructionism. Ablex Publishing, 1991.

Johnson, Laurence F., Rachel S. Smith, J. Troy Smythe, and Rachel K. Varon. Challenge-based learning: An approach for our time. The new Media consortium, 2009.

King, Alison. “From sage on the stage to guide on the side.” College teaching 41, no. 1 (1993): 30-35.

Nelson, Robin. Practice as research in the arts: Principles, protocols, pedagogies, resistances. Springer, 2013.

Plantinga, Carl. Screen stories: Emotion and the ethics of engagement. Oxford University Press, 2018.

O’Toole, D (2019). Translating The Experience of Drowning To Film Form, Doctoral Diss, Queens University Belfast

Papert, Seymour. “Teaching children thinking.” Programmed Learning and Educational Technology 9, no. 5 (1972): 245-255.

Plantinga, Carl. Screen stories: Emotion and the ethics of engagement. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Shanahan, Ann M., Prudence A. Moylan, Betsy Jones Hemenway, Bren Ortega Murphy, Jacqueline Long, Susan Grossman, Hector Garcia, and Mary Dominiak. “Performance: An Approach to Strengthening Interdisciplinarity in Women’s Studies and Gender Studies.” PARtake: The Journal of Performance as Research 1, no. 1 (2016).

Sullivan, Graeme. “The art of research.” Studies in Art Education 55, no. 4 (2014): 270-286.

Sullivan, Graeme. “Research acts in art practice.” Studies in art Education 48, no. 1 (2006): 19-35.

Vygotsky, Lev Semenovich, and Michael Cole. Mind in society: Development of higher psychological processes. Harvard university press, 1978.

Filmography

A Clockwork Orange. (1971), Directed by Stanley Kubrick., USA: Blinder Films.

Birth of Helena (2022) Directed by Hana Mohamed, Portugal, FilmEU

Blue Is The Warmest Colour. (2013)., Directed by Abdellatif Kechiche, France, Belgium, Spain: Quat’sous Films et al.

Blue Velvet. (1986)., Directed by David Lynch, USA: De Laurentiis Entertainment Group (DEG).

Boys Don’t Cry. (1999)., Directed by Kimberley Peirce., USA: Fox Searchlight.

Queen of Ireland. (2015)., Directed by Conor Horgan., Ireland: Blinder Films.

Live and Let Live (2022) Directed by Jaka Prosenik, Belgium, FilmEU

Midnight Cowboy. (1969)., Directed by John Schlesinger., USA: Jermome Hellman Productions et al.

Skam. (2015)., Directed by Julie Andem., Norway: Norsk Rikskringkasting (NRK).