Abstract

The Communication technologies spectacular advance in the last decade has led to the emergence of a whole new movement of social media based on a philosophy of collaborative and horizontal work. The sharing economy represents the world consumer revolution. The digital push that has happened since the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin-American countries has rethought the way in which business are done and have fully digital administrative processes. This article is a journey through the concepts of the platform economy, the digital economy, the collaborative economy and the Long Tail Theory applied to the creative industries and the film industry.

Keywords: Collaborative, Platform economy, Digital economy, Long tail, Creative industries.

Introdução

El espectacular avance de las nuevas tecnologías de la comunicación ha propiciado el surgimiento de todo un movimiento de nuevos medios ciudadanos basados en una filosofía de trabajo colaborativo y horizontal. La economía colaborativa representa la revolución del consumo mundial. El empujón digital que ha sucedido a partir de la pandemia del COVID-19, ha replanteado la forma en cómo se hacen negocios y tener procesos administrativos totalmente digitales.

Internet as a catalyst for the platform economy

The social, political, economic, and technological transformations that are taking place make it necessary to rethink those socially accepted postulates from the 20th century so they can be adapted to the reality of the new millennium.

The information age is the name given to the period in human history that is linked to information and communication technologies.

The enormous potential of information and communication technologies (hereinafter ICT) has evolved from the rudimentary version of the web 1.0, through the social change that meant the power of the crowd in the web 2.0 and the hash tag (#), until we reach the incipient web 4.0, in which smart devices fulfill our orders: request a taxi, buy flights or order food at home. Some of those issues that 30 years ago were utopias have come true over time.

Web 1.0 was static, in Web 2.0 the social took center stage, in 3.0 the content and knowledge were related more efficiently. Web 4.0 focuses on offering a smarter, more predictive behavior, so that we can, just by giving an order, launch a set of actions that will result in what we are requesting.

The normalization in the internet use, ICT and social networks, has been changing the face of internet portals, from traditional web pages, which only provide information, to applications, which have made life easier since the appearance of the smartphones. All kinds of platforms have emerged, individuals interact with web pages for various reasons, such as paying taxes, shopping in the supermarket, accessing video on demand systems or receiving a free course to learn a language.

If the Industrial Revolution was organized around the factory, today’s changes are organized around platforms, algorithms applied to enormous databases running in the cloud. The salience of these digital platforms suggest that we are in the midst of a reorganization of our economy in which the platform firms are developing power roughly equivalent to that of Ford, General Motors, and General Electric of earlier eras. (Kenney, M y Zysman 2015,7)

New economy / Digital economy

The internet consolidation as an extensive window of consumption, information and entertainment has made communication companies adopt new models for the industry, which has been forced to renew its analogous routines, redefining the traditional processes of content audiovisual creation, commercialization and even reinventing business models.

In a digital consumer environment characterized by timelessness, ubiquity, connectivity, multimodality and interactivity in the relationship between creator and user, today new dynamics are imposed in which not only value, originality and treatment are important content, but also its adaptability to new devices.

In fact, the most relevant and decisive change in the contemporary media ecosystem is the consolidation of the smartphone as a mass device for online consumption. Although originally conceptualized as a more or less elitist instrument that could also be used to support management in political and economic areas, the mobile phone has spread so strongly on a global scale that the figures regarding its possession and use determine the communication and planning strategies at an informative, persuasive and commercial level.

Since the smartphones appearance, a great innovation arises in terms of mobility and interconnectivity between telephones and computers; Thanks to this, a new economic order has been born led by these technologies, which allow the consolidation not only of new products but also of new industries and new economic dynamics, as Varela (2005) mentions in his essay Internet as Platform of the New Economy: “the most important thing for this new area is the interconnection capacity that develops between communication nodes, huge networks that transmit information.”

From these transformations the concept of New Economy was coined, which is fundamentally based on the rapid development of applications of the thriving information and communication technologies.

However, the term New Economy rests on the same paradigms, the same concepts and the same theories as the “Old Economy” studies; the author José Ignacio López Sánchez proposes the concept of Digital Economy.

Companies from the most diverse sectors are incorporating the technological aspect into their commercialization, through online sales portals, application development, among other ways; they are also trying to achieve a positive effect on economic growth and to increase their productivity. The European Union itself, through the calls of the Media Creative program, seeks to promote new distribution models to allow the development of new online-oriented business models.

The most important aspect of the new economy is not, therefore, the obvious growing weight of the information technology sector or the proliferation of dot-coms and other start-ups that have found a new channel to reach the final consumer, but the way in which ICTs allow the development of economic exchange. (Pampillón, 2001, 46)

The digital economy focuses on the accumulation capacity and knowledge application acquired by the agents, in addition to the information administration they possess.

María García and Celia Saras, from the “Catedra Telefonica”, propose a definition of the digital economy that we will adopt for the purposes of this study. It is based on using some or all of the technological resources available to apply them to a business idea in order to optimize all processes and increase profits, that is, to migrate to an economy where the use of information technologies is generalized in all economic, cultural and social activities.

The digital economy has provided opportunities for new forms of economic practice, forms that entail a very different kind of moral economy than market capitalism. At their purest, there forms deliver economic benefits as gifts and depend on cooperation without authority. [..] However, the digital lifeworld economy has been steadily colonized by capitalist business, which has frequently found ways to incorporate forms of gift and cooperation into profit-oriented business models. (Elder-Vass 2017, 2)

Collaborative Economy

The digital economy is closely linked to the concept of the collaborative economy. There are some texts where digital economy and collaborative economy are used interchangeably, when in reality they are not the same.

The term “collaborative economy” refers to the new systems of production and consumption of goods and services that have emerged thanks to the advances in information technology to exchange and share said goods and services through digital platforms. “Collaborative economies are new forms of association of individuals connected to each other, who create, distribute and consume goods and services without the need for intermediaries.” (Bocanegra y Ernesto 2017, 4)

In the collaborative economy, agents tend to act simultaneously as very small consumption and production units. It must be taken into account that this type of economy is very difficult to carry out without a network such as the Internet, since it requires many agents to be connected simultaneously.

The terms shared economy, collaborative economy, collaborative consumption, participatory consumption, circular economy, refer to the new economic models in which activities are facilitated by collaborative digital platforms, creating an open market for the temporary use of goods or services that are usually provided by individuals. Their central axis is the active participation of citizens and their ability to influence the market in a more horizontal relationship between the parties. (Vilalta 2018, 267)

It is a growing and innovative economic model based on the purchase, sale, rental, loan, gift or exchange of goods and services through the new uses of the Internet, mobile technologies and communities. It is a model that is based on mutual aid and collaboration between individuals. Vassilis Hatzopoulos in his book The Sharing Economy and the laws of the European community mentions that:

… From online marketplaces, to distribution platforms like APP to social networks wikis and even online dating platforms, almost all the products, services and knowledge one could be looking for are just a click away. […] The most recent advances in digital technology, such as the Internet of Things (IoT), the 5G network, the cloud storage service, data analytics and robotics, have created the ideal place for you to use the most varied online platforms for various functions proliferate. All this development has led us to the era of the 4G Industry and we are becoming prosumers, co-producers of what we consume, by actively participating in digital platforms and exploiting technological progress. (Hatzopoulos 2018, 2)

The collaborative economy is an access to new professional activities, since it allows both the appearance of new types of providers that offer services until now restricted to companies and that of new business models that years ago seemed impossible. According to the Sharing Spain report, this type of economy has more presence in the tourism, transport, artisanship sector, and in all kinds of goods that can be rented or resold.

Basic activities in the collaborative economy

Regardless of the purpose pursued by collaborative economy companies, some authors distinguish four basic activities:

The first of these is collaborative consumption, which provides access to goods and services through the following legal-economic instruments: barter, rental, loan, trade, leasing, exchange, resale and exchange. It includes both redistribution markets - where goods are resold or redistributed from where they are not needed to where they are; product and service systems, in which you pay for access to goods and not for their acquisition—, such as collaborative life systems, where intangible assets such as time, skills and space are shared and exchanged.

The second activity refers to collaborative production, in which groups, networks or individuals collaborate in the design, production or distribution of goods. It includes collaborative design - we work together in the design of a product or service through an open call to the public, a design report or a challenge -, the collaborative elaboration of products or projects and the collaborative distribution, where the distribution of goods is organized and carried out directly between individuals.

Collaborative learning, that is, constitutes the third by learning experiences open to anyone, resources and knowledge are shared to learn together. It includes free access to courses, readings and educational content, it also opens the option to teach or share skills. This has been greatly enhanced by the conditions of the pandemic. Taking classes online has become the new normal.

Finally, the fourth has to do with collaborative finance, or financing, loan or investment services, which are provided outside of traditional financial entities. This is the case of crowdfunding or direct and mass financing of a specific project; peer-to-peer lending, which connects those who want to invest with those who need a loan; the complementary currencies or alternative currencies to those of legal use, to which certain groups recognize value for certain purposes; and group insurance policies.

Characteristics of this economy include the following abilities:

- Responds positively to high demand levels without long-term commitments.

- It grows or decreases depending on the demand for products and services.

- Trade anytime, anywhere, under any conditions

- The amount of goods and labor depends on the unit of production.

- Provides transparency of both operations in real time, both external and internal visibility.

Peer to peer (P2P)

The sharing economy has gained relevance thanks to collaboration between peers. It is also known by the acronym P2P, where the exchange of products and services is carried out between equals and not from traditional structures, in which people consume in a business and that business buys from another large corporation. In the network between equals, finding and making transactions has been made easier thanks to ICT and the proliferation of platforms that allow this exchange.

The germ of this model is in the social networks, a connection system between computers, that is, from computer to computer. This allows the vertical connection between individuals through the Network, without the need to use fixed servers. What was originally used to quickly and efficiently share documents at work, has become a popular method of sharing all types of files between people around the world through so-called P2P programs. (Celaya y Vázquez 2016, 40)

Onset of the new millennium, a series of P2P pages allowed music and software to be shared over the internet, later known as Torrentso as P2P programs.

Bauwens, in his text The Political Economy of Peer Production, makes some distinctions:

P2P does not refer to all the processes that take place in distributed networks: P2P specifically designates those processes that seek to increase the participation of equipotential participants. The overall P2P processes characteristics are:

1. They produce value through the free cooperation of producers who have access to distributed capital: this is the P2P mode of production, a ‘third mode of production’ different from profit-oriented or public production by state-owned companies. Your product does not exchange value for a market, but uses value for a community of users.

2. They are led by the community of producers itself, and not by market distribution or the corporate hierarchy: this is the P2P mode of government, or ‘third mode of government’.

3. Make use value freely accessible on a universal basis, through new common property regimes. This is their distribution or ‘mode of ownership between equals’: a ‘third mode of ownership’, different from private property or public (state) property. (Bauwens 2014, 16)

The traditional economy is driven by markets and by hierarchical firms or state organizations, but Bauwens saw a third possibility, which he called “commons-based peer production.” “Production between equals” and “based on the commons” because the result is not owned by anyone. Those who take part do so on egalitarianism.

The exchange has been gaining place over purchase. Collaboration and the exchange of roles between producers and managers is more fluid with the intensive use of technological resources.

The Long Tail

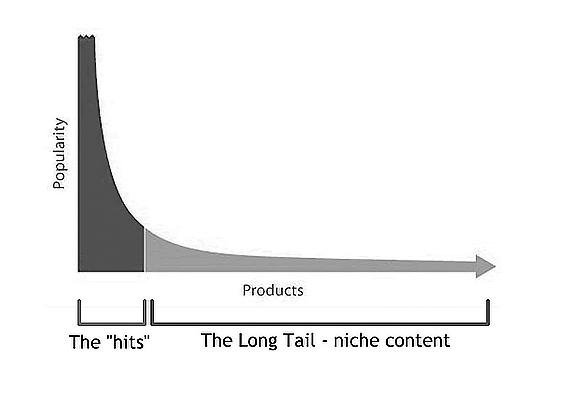

The long tail theory predicates that the Internet has spawned an unlimited number of retail sites that are quickly, easily and cheaply accessible to consumers. Likewise, on the supply side, the Internet provides a parallel level of accessibility to an unlimited array of vendors and their products/services. Anderson’s theory argues that because of this unlimited distribution and total supply/demand accessibility, a huge paradigm shift has occurred.

By lowering production and distribution costs, especially online, there is now less need to crowd products and consumers into one-size-fits-all containers. In an era without limitations of the physical space of the shelves and other bottlenecks of the distribution, the products and services with a very defined target can be as economically attractive as those of popular consumption. (Anderson 2006, 87)

Figure 1 – The Long Tail, made by Milosz Krasinki

The Long Tail Theory is nothing more than the abundance of infinite options. In these times, in which it is no longer essential to have a physical point where consumers get to make their purchases, since they can do them from the virtuality of the Internet, distribution becomes cheaper and consequently it becomes more varied and abundant. This applies to everyday products and also for cultural consumption; from the most standardized entertainment industry, it is seen as a struggle between the traditional and online consumption.

In 2020 during the pandemic, the film industry has had an unprecedented setback. Big film studios like Disney and Warner finally understood that their business models migrated from the big movie theaters to the small television screens in the home. This fight embodied between the small and the big screen, seems to finally have a winner. The abundance of options is the most attractive thing for the audience and has been a key part of Netflix big success.

The first force of the Long Tail is the democratization of the tools of production. The personal computer, which has put everything from print shops to film and recording studios within the reach of anyone. The power of the personal computer means that the categories of “producers” have multiplied by the millions. This is the force that extends the tail to the right, multiplying the number of goods available.

The shift from the generic to the specific does not mean the end of the existing power structure or a total shift to a return to fully amateur culture. Today, it is simply a shift in the equation, an evolution from the ‘O’ era to an era of successes or niches (standardized culture vs. subculture) to the ‘Y’ era. Today, our culture is more and more a mixture of head and tail, institutions and individuals, professionals and amateurs, mass culture will not fall, it will simply have less mass. And the niche culture will be a less underground culture. (Anderson 2006, 125)

The platforms at Web 2.0 promised to create a more egalitarian world in which artists could connect directly with global audiences, but at the end they have come to offer best sellers. What the Long Tail Theory proposed is very interesting, but the vast majority of revenue is at the head of the tail. And it is a lesson that companies must learn. Even if you have a long-tail strategy, it is better to have a head, because that is where all the income are.

Anderson’s theory, although hopeful about what would come in this new millennium, time has shown that businesses are not really in the niche, the long tail is not what generates the great sales, whilst it is true that the sum of Efforts have been the key to the success of companies such as the Mexican cinema chain Cinepolis, which not only opens in theaters, but also through its streaming platform Cinepolis Klic; or like the recent case after the pandemic, where studios like Warner or Disney have decided to make their blockbuster premieres on streaming platforms. In other words, the sum of the old efforts plus the use of information technologies, this is the main Long Tail Theory dogma that has ended up becoming a reality.

Gig economy

The new panorama created by digital platforms, especially those for employment or crowdsource applications, has brought the GIG ECONOMY concept.

Gig is slang for a musical engagement in which musicians are hired. Originally coined in the 1920s by jazz musicians, the term, short for the word “engagement”, now refers to any aspect of performing such as assisting with performance and attending musical performance. More broadly, the term “gigging” means having paid work, being employed.

About the gig economy, Donovan, Bradley, & Shimabukuro, (2016) mention in their work What Does the Gig Economy Mean for Workers?:

Prospective clients request services through an Internet-based technological platform or smartphone application that allows them to search for providers otr to specify jobs. Providers (workers) engaged by the on-demand company provide the requested services and are compensated for the jobs. (Donovan et al. 2016, 7-8)

This type of economy can serve as a kind of “meanwhile” in the world of employment, of temporary employment, of course. It provides opportunities to generate income when circumstances do not accommodate a traditional full-time job.

Work is being reformatted. For many, traditional employment – a single organization providing long-term engagement, usually with some form of social benefits — is giving way to gig and contract arrangements. Not surprisingly, business strategies shape job quality. Even in low-margin, low-price business there are “better” job strategies that can provide workers higher wages and benefits and contribute to a strengthened competitive position for the firm. In the aggregate, the shifting place and character of entrepreneurship and the reorganization of work may powerfully alter the distribution of wealth and income in societies. (Kenney y Zysman 2015, 4)

Some platforms that offer these types of jobs can work from and for the local market and others globally. This concept is relevant because in the film industry temporary work and the “meanwhile” are among the most abundant. The gig economy would not only serve as an option to generate income, but also as a learning bridge between the more amateur sectors.

Cultural industries and creative economies

Speaking of cultural industries and the advances that technology has brought to economic revolutions, there are several studies that speak about the creative economy. Diverse institutions have defined the cultural industries and the creative economy. The following definitions appear at La Economia Naranja book1

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO)

“Cultural and creative industries are those that combine the creation, production and commercialization of creative content that is intangible and cultural in nature. These contents are normally protected by copyright and can take the form of a good or service. They also include all artistic or cultural production, architecture and advertising.”

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)

“Creative industries are at the center of the creative economy, and are defined as cycles of production of goods and services that use creativity and intellectual capital as the main input. They are classified by their role as heritage, art, media, and functional creations.”

Organisation Mondiale de la Propriété Intellectuelle (OMPI)

“The industries protected by copyright are those that are engaged in, are interdependent, or that are directly or indirectly related to the creation, production, representation, exhibition, communication, distribution or sale of material protected by copyright.”

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (CEPAL)

“The content industries are: publishing, film, television, radio, record company, mobile content, independent audiovisual production, web content, electronic games, and content produced for digital convergence.”

The Green Paper2 published by the European Commission, define the cultural industries as:

Cultural industries are those industries producing and distributing goods or services which at the time they are developed are considered to have a specific attribute, use or purpose which embodies or conveys cultural expressions, irrespective of the commercial value they may have. Besides the traditional arts sectors (performing arts, visual arts, cultural heritage – including the public sector), they include film, DVD and video, television and radio, video games, new media, music, books and press. This concept is defined in relation to cultural expressions in the context of the 2005 UNESCO Convention on the protection and promotion of the diversity of cultural expressions.

Creative industries are those that use culture as a material and have a cultural dimension, although their production is mainly functional. These include architecture and design, which integrate creative elements into broader processes, as well as subsectors such as fashion design or advertising.

At a more peripheral level, many other industries rely on the content production for their own development and therefore exhibit a certain degree of interdependence with cultural industries. These are, among others, tourism and the ICT sector.

The creative economy also proposes a different social and ecological model. More than a conservative speech on cohesion and equity says Richard Florida in UV Creative Industries; the key values are diversity and tolerance.

The so-called Knowledge Economy operates in areas with specific development schemes, so that new areas of competence generally referred to as intangible assets or Digital Assets, replace the principles on which traditional competitive advantages are based. (Varela 2005, 25)

This is how the companies producing intangibles will try to create a vast network of users, that is, they will seek that their products are installed in the largest number of devices, since their value lies in the number of users, in the dissemination and in the use on a large scale.

The cultural and creative industries face a rapidly changing context characterized, in particular, by the speed of development and implementation of digital ICTs on a global scale. This driver has a major impact on all sectors of the entire value chain, from creation to production, distribution and consumption of cultural goods and services.

Technological innovation

Technology and the availability of broadband infrastructure in urban and rural areas open up new opportunities for creators to produce and distribute their works to a wider audience and at a lower cost, regardless of physical and geographical limitations. Thanks to this, and as long as the providers of cultural content make full use of ICT and the traditional patterns of production and distribution are reexamined, creators will be able to have larger audiences and markets, and a more diverse cultural offer will be provided to citizens. At the same time, the implementation of ICTs depends on the availability of diversified and high-quality cultural content. Consequently, cultural content plays a leading role both in the acceptance of these new technologies by the general public and in the development of e-skills and the improvement of the media literacy levels of European citizens.

In his book Media and Participation, Nico Carpentier has a section dedicated to technology, where there are meanings about how technology has been associated with progress, since it is seen as a driving force: a linear process of social improvement.

The new demands of the digital economy and globalization are changing the relationship between the economy and culture. The Internet, digitization and technological innovation are influencing the creation, production, consumption and distribution of a variety of cultural services, objects and products. This new economy, through the market, drives the accelerated conversion of culture into a business, and, through a wide range of cultural services, is demanding the digital reconversion of companies and agents involved in cultural production. (Canclini 2012, 112)

The extraordinary circumstances that the COVID-19 pandemic has brought, is precisely a “digital push” to the digital transformation of Latin American countries, accelerating their process of adopting technology, for teleworking, electronic commerce and in general, the digitization of various productive and even administrative processes.

This helps Creative Industries to also find in this digitization a hope to survive and do business. And as for the film industry specifically, which has been hit hard by the pandemic; this digital revolution allows the search for new production and distribution models more in line with the current situation.

Final Notes

1Felipe Buitrago e Iván Duque, La economía naranja: una oportunidad infinita (Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo, 2013) 37.

2European Commission, Green Paper: Unlocking the potential of cultural and creative industries (Bruselas, 2010), 6.

Referências bibliográficas

Anderson, Chris. 2006. The Long Tail: Why the future of business is selling less of more, New York, Hyperion Books.

Bawens, Michael. 2014. La economia política de la producción entre iguales. Hypertexto (enero-junio): 15-29

Bocanegra, Ossa, Camilo Ernesto. 2017. Economías colaborativas: regulación y competencia. Revista de Derecho Privado (enero-junio): 1-22

Buitrago, Felipe e Iván Duque. 2013. La economía naranja: una oportunidad infinita. Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo. https://publications.iadb.org/publications/spanish/document/La-Econom%C3%ADa-Naranja-Una-oportunidad-infinita.pdf

Canclini, Nestor, Francisco Cruces y Maritza Urteaga Castro Pozo. 2012. Jóvenes, Culturas Urbanas y Redes Digitales, Madrid, Fundación Teléfonica.

Celaya, Javier e José Antonio Vázquez. 2016. Consolidación de los modelos de negocio en la era digital. Dosdoce.com. http://blogconlicencia.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Consolidacion-de-los-modelos-de-negocio-en-la-era-digital-2016.pdf. Accedido el 20 de octubre de 2017.

Comisión Europea, 2010. Libro Verde: Liberar el potencial de las industrias culturales y creativas. Bruselas. https://oibc.oei.es/uploads/attachments/68/Libro_Verde_-_Liberar_el_potencial_de_las_insdutrias_creativas_y_culturales.pdf

Donovan, Sarah, David Bradley, Jon Shimabukuru. 2016. What does the Gig Economy Mean for Workers? Cornell University ILR School (Mayo): 1-16

Elder-Vass, Dave. 2017. Lifeworld and system in the digital economy. European Journal of Social Theory. 1-18.

Hatzopoulos, Vassilis. 2018. The Collaborative Economy and EU Law, Oregon. Bloomsbury.

Kenney, Martin, John Zysman. 2015. Choosing a Future in the Platform Economy: The Implications and Consequences of Digital Platforms in Kauffman Foundation New Entrepreneurial Growth Conference (Draft) 1-23.

Pampillón, Rafael. 2001. La Nueva Economía: análisis, origen y consecuencias. Economía Industrial 340: 43-50

Varela, Mauricio. 2005. Internet como la plataforma de la Nueva Economía El Cotidiano 130 (marzo-abril): 24-30