Abstract

The paper analyses pictorial elements of composition and their use in films, taking Sergei Parajanov’s The Colour of Pomegranates (1969) as a case study, and comprises three parts. In the first chapter of the paper, different approaches to the term ‘pictorialism’ are explained; frontality and stillness derived from traditional art forms are discussed with examples of such references in paintings, architecture and films. The second part includes a brief introduction to the Soviet avant-garde cinema and follows the journey of the making of The Colour of Pomegranates. Upon reflecting on the theoretical part, the third chapter analyses frontality in the original Armenian cut of The Colour of Pomegranates by Sergei Parajanov and the references used from Transcaucasian Miniature art, Armenian culture, religion and traditions in assembling the filmmaker’s visual choices. The study is based on specific scenes from the film, presenting Parajanov’s use of frontality from a mosaic of perspectives, which the filmmaker applied to create the poetic world of ashugh Sayat-Nova.

Keywords: Pictorialism in cinema, Frontality, Stillness, Sergei Parajanov, The Colour of Pomegranates

Introduction

As a medium, cinema resembles the other visual art forms. Directors often use painting, literature, photography, music and dance to give form to their works. Filmmakers have been in pursuit of building exceptional visual narratives by creating stylized images that are based on personal vision shaped by cultural heritage and distinct ways of using art references. To achieve that they turn to the history of art to expose emotions, establish psychological context, and maintain identification between the viewer and the characters.

Using paintings as references is an effective tool that can place the viewer from the personal, isolated involvement to the unconscious collective engagement in the narrative. Another way of referring to art history is to shoot an entire film in the style of a particular artist or a movement contemporary with the film’s narrative and setting.

It is important to study the sources and art techniques used in films to understand the impact of the filmmakers’ choices. There are several reasons why filmmakers use traditional art media to build their films: they use art references as subplots, to maintain a psychological connection with the audience, to give clues about the story and enrich the narrative, to add emotional context, draw attention to specific details, and make the viewer identify and empathize with the characters.

Cinema inherited the codes of perspective from painting and literature, and this heritage demonstrates how we perceive reality from a cultural perspective. It becomes difficult for the viewer to observe a specific landscape outside his social context. According to Nietzsche (1968, p. 89), people mirror themselves in the objects and the surrounding world, thus comprehending “beauty” in the things that reflect them. Individuals see the surrounding world as a part of their identity, and by looking at a particular landscape, they transform it into a spiritual phenomenon. And the pre-cinematic heritage of social codes interprets how the photographers and filmmakers place things within the frame to comply with aesthetic values, human emotions and ideas. There are cultural codes homogeneous to everyone and those that are particular to people living in specific territories.

It is hardly possible to discuss Soviet Armenian filmmaker Sergei Parajanov’s The Colour of Pomegranates («Նռան Գույնը», 1969) outside the cultural context. The film follows the Armenian ashugh (troubadour poet) Sayat-Nova, revealing his life visually and poetically. Through a chaptered narrative (Childhood, Youth, Prince’s Court, The Monastery, The Dream, Old Age, The Angel of Death and Death), Parajanov presents multi-faceted pieces of contemporary life and takes the viewer into the character’s desires and dreams. The visual narrative is accompanied by music, sound and singing, but there is little dialogue in the film.

In the Preface of the book The Colour of Pomegranates (2018, p. 7) that accompanies the restoration of the film’s uncensored original Armenian version (restored by Cineteca di Bologna and The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project), Martin Scorsese asserts, “On a very basic level, it’s a biography of the Armenian poet Sayat-Nova, but before all else it’s a cinematic experience, and you come away remembering images, repeating expressive movements, costumes, objects, compositions, colours.”

Although Sayat-Nova lived in the 18th century, the visuals of The Colour of Pomegranates seem to be from the medieval ages. Parajanov applied Miniature art from the illuminated manuscripts when composing the elements within the frame. The artworks are used as sources for compositions, they also appear in the film (particularly in the first ten-minute sequence) in close ups and extreme close ups. And yet, the choice of citing the miniatures is not solely for visuals: in the third chapter, the protagonist of the story becomes a monk: the religious context is omnipresent in the film as are the hidden connotations of desire opposed to the sacrifice of the joys of life.

According to Parajanov, he has always been addicted to painting and has long been accustomed to the fact that he perceives the shot as an independent pictorial canvas. He also knows that his direction gets dissolved in painting and that is its first weakness and its first strength. Parajanov often turns to pictorial and not literary solutions in his works. “And the literature that gets close to me is the one that is a transformed painting in its essence.” (Parajanov. 2001, p. 40)

Soviet Armenian filmmaker Sergei Parajanov derives frontality from the miniatures of the Armenian and Persian illuminated manuscripts and medieval icons while making pictorial decisions and uses it as an expression of stillness, as a representation of duality, as a symbol of transformation, as a depiction of divinity, and as a means to guide the attention in his film The Colour of Pomegranates, which helps him convey the poetic world of ashugh Sayat-Nova. And with the use of the pictorial elements Parajanov emphasizes how the secondary characters become silent witnesses to the events happening on the screen and creates a special bond between the audience and Sayat-Nova.

As the basis for my research I will take the new 4K restored version that includes the original Armenian version of the film (Parajanov’s and Ponomarenko’s cut). While the most known version is the Yutkevich’s cut, released in different parts of the Soviet Union.

Chapter 1: Pictorialism & Frontality

1.1 Pictorialism in Art

Works of art mediate social assumptions and cultural patterns. To apprehend images, the viewer needs more than identification of the objects within the frame. It requires attention to the landscapes and spatial structures, recognition of the connection between the objects, analysis of the events and actions based on experience and knowledge and pictorial thinking.

Narrative in cinema is often dependent upon cultural codes to add layers of meaning to a film. When watching a film, audiences bring their cultural perspective to the picture. And while this may not change the meaning of a blockbuster film, the independent and avant-garde cinema often requires cultural knowledge as it can be key to understanding the film.

French film theorist and scholar Christian Metz (1986, pp. 38-39) distinguishes between specialized and cultural codes in cinema. According to him, the former is purely cinematographic, consisting for example, of camera movements, montage, optical effects. While cultural codes are perceptual and iconographical, they are well-incorporated in a certain culture or cultures and are considered natural. So, with the use of specialized codes filmmakers determine what we see, while the cultural codes help us interpret that which has been seen.

Filmmakers like Sergei Parajanov, Béla Tarr, Theo Angelopoulos, Andrei Tarkovsky pictorially present the images within their films which urges the viewers to use their experience to fill the frame with personal subjective feelings and thoughts, and find hidden connotations, which directs the spectator towards an extended perceptual experience of the piece. These images owe their existence to cultural codes as it is due to them that the viewer perceives similarities between a physical object and an iconic representation of it (Eco, 1972, p. 200).

Soviet Armenian filmmaker Sergei Parajanov uses cultural elements in abundance and produces pictorial works which function as a bridge between history, art and aesthetics. As a bearer of a Soviet culture, he presents the Ukrainian Hutsul society in Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1965) and the Armenian culture in The Colour of Pomegranates (1969). Parajanov uses elements of cultural heritage, like landscape and building, as well as costumes, distinctive behavioral patterns and narrative devices derived from history to recreate the identity of Ukraine and Armenia on screen. The iconography of the shots, their use of certain conventional correlations in artistic representation constituted a code, which was culturally specific to the artist’s society, and strange for the other cultures. So, the audience can recognize the cultural elements, though they will not connect with the films as natives do because they did not inherit the same codes.

Pictorialist filmmakers use both historical and contemporary filmmaking practices to construct the objects within the frame. The knowledge and understanding of history and art theory is central to understanding the development of pictorial processes. Part of understanding a film is recognizing the references used in them. Thus, films can be analysed in relation to painting, architecture, photography and theatre. Cinema is linked to traditional visual art forms with the use of pictorial stillness and composition, photographic movement and absence of it. Filmmakers make selective choices of using specific images in relation with audiovisual elements to complement their aesthetics.

According to film theorist Jarmo Valkola (2016, p. 31), the roots of pictorialism originate in the 16th century traditions of landscape painting by German, Dutch and Flemish artists. And the movie camera as if it is a human onlooker, inheriting the codes of perspective from literature and painting, provides a unique opportunity for landscape allegory. David Melbye (2010, p. 3) defines cinematic allegory as “[…] an assembled narrative mode, wherein the principal characters move beyond their normal protagonist or antagonist functions and into a symbolic dimension of meaning.” So, pictorialist filmmakers use locations not to merely support the setting: they can be the reflection of the inner state or the mental universe of the protagonist, have psychological dimensions, even be a character on their own.

The word ‘pictorial’ can be used in relation to visual arts and to literary writings (Pearce, 1983, p. 5). Painters, sculptors, writers, photographers, filmmakers and performance artists all deal with object, time, space, character, relations with the use of similar set of values; as a novelist creates the vision of the world with describing the elements, also establishes the point of view of the story. The same way that we look at the screen and view objects, characters, their actions and relations from a specific perspective. Literary critic Viola H. Winner (1970, p. 70) has a similar perspective, defining pictorialism as the practice of describing people, places, details in the scenes as if they were paintings.

In stage pictorialism dominates the setting and defines the relationship between the set, the actors and scenic transformations (Brewster & Jacobs, 1997, p. 212). Certain characteristics from painting are transported to theatre, namely the placement of the contrasting elements across the stage and stillness which gives the audience time to read the scene. So, in theatre performances pictorialism helps the creators direct the spectator’s gaze towards the key objects, characters and actions in the scene. They draw attention through the way they position the objects on stage, creating geometric lines and figures when the actors are in motion or motionless, and with lighting.

Within the filmic universe stylized tones, schemes and expressions help to form pictorial images. Literary scholar Jean Hagstrum (1958, pp. 54-56) asserts that an image or a description is ‘pictorial’ if it can be translated into a visual art. He argues that this doesn’t mean that images or descriptions have to include solely painterly elements, merely that the leading details should be pictorial.

Pictorialism is “… an audiovisual endeavour, and a cinematic tableau that connects diverse forms of art, architecture, photography, cinema and painting.” (Valkola. 2016. p. 1) It is applied to expand and heighten the power of images and sound, and the diverse combination of cinematic and non-cinematic codes with art references and personal aesthetics and expressiveness of a filmmaker transports the effects of the contemporary cinema into higher dimensions.

Pictorialism can be used to describe works of different art forms: painting, literature, cinema, architecture, photography, theatre. In cinema it unites temporal and spatial elements and with the use of stillness and through presenting images as symbols and signs, enhances the visual story and creates an extended perceptual experience for the spectator. So, the compositional force in pictorialism is born out of the use of lighting, slow and minimalistic movements, orderly positioning of the objects and characters, and stillness and perspective.

1.2 Frontality and Stillness

In classical cinema the screen is regarded as a plate-glass window where with the two-dimensional camera, filmmakers create the illusion of depth by using different depth cues. When a character moves in the space within the frame s/he creates an ongoing succession of overlapping shapes and planes and with the camera sliding through the mise-en-scène, the perception of the screen as a two-dimensional flat surface gets shattered. The filmmakers add texture, pattern, colour to specify the objects in the space and guide the attention of the viewer using the selective focus. With silhouetting, side lighting, contrasting, diffusing, backlighting filmmakers separate the figure of the characters and objects from the background, as a result, creating depth. Thus, the proper use of lighting and contrasting, the application of texture, colour, pattern, the adjustment of focal length, and movement are the key indicators of the representation of depth in cinematic space. At the same time, filmmakers often use stillness to suppress the illusion of kinetic depth in avant-garde films and create pictorial images by using art works as references to construct the space.

Cinema uses intermediary approach when compared to traditional visual art forms, where “[…] the architectural, photographic, painterly and pictorial dimensions are united and dialogically composed in moments of pictorial stillness during the narrative” (Valkola, 2016, p. 20). A still photograph or a painting comes along as a frozen moment in time that lacks motion though implies it. While the features of cinematic motion in combination with a static scenery produce an image with pictorial quality filled with stillness and slow tempo.

Even though the traditional visual art forms don’t move and cannot produce motion, the notion of implied movement is essential to their aesthetic. And the stillness in a painting, a sculpture or a photograph ‘freezes’ the moment to make room for deep reflection. Traditional art forms often require the viewer to spend some time staring and examining the artwork to appreciate it, identifying the techniques, the actions and events, the concept, possible hidden connotations, etc. Unlike film, theater or new media, paintings do not consider time an active dimension of the piece; on the contrary, they provide us with several timeless moments. “The works of both painter and sculptor are created not merely to be given a glance but to be contemplated - contemplated repeatedly and at length.” (Lessing, 1984, p. 19)

In The Monk by the Sea (Figure 1.1) by a 19th -century German Romanticist Caspar David Friedrich three quarters of the canvas comprises a wide, empty landscape which depicts a blue-gray sky and green sea. There is an uneven strip of yellowish brown in the bottom part of the painting, and on the left part the piece depicts a small figure with an identifiable dark robe of a monk. The landscape is a piece of minimalism and stillness, and with the lack of depth and details the artist avoids disruption of the pictorial restraint and fills the canvas with large expanses of colour, emphasizing the mystery of the unknown, nature and the divine (Wolf, 2003, pp. 31-34). In fact, the man is in stillness himself: while he stands alone and motionless with his face away from the viewer, we look at his solitude and share the feelings of humility and awe. Caspar David Friedrich juxtaposes his lone figure to the vastness of his surroundings and by hiding his face, he keeps the spectator in suspense and guides the attention towards the space within the frame. He prefers to transfer the sensorial information so that the viewer experiences a range of emotions rather than feels the temptation to invent a narrative story, so the latter becomes of secondary importance.

Figure 1.1 - Caspar David Friedrich. (1808-1810). The Monk by the Sea, oil painting, Alte Nationalgalerie (Berlin)

Artists apply art elements and principles (shape, form, colour, texture, rhythm, etc.) to determine the place of frontally oriented planes in pictorial space and to make depth relations visible. According to art and film theorist Rudolf Arnheim three-dimensional space offers complete freedom with “[…] shape extending in any perceivable direction, unlimited arrangements of objects, and the total mobility of a swallow.” (1974, p. 218) Visual imagery relies on these three spatial dimensions, and the level of perception can go beyond the observed information through imagination and intellectual construction. When looking at a painting or a still photograph the viewers exercise their knowledge of physical space to interpret spatial relations in an art piece.

In film cinematographers construct the shot using the principles of filmmaking that directly echo those of academic painting. Classical narration in cinema often needs image composition and editing to create a meaningful representation of three-dimensional space. In the classical Hollywood cinema narrative causality is often given dominance while the setting is subordinated and coherent with the story, and is used as a complimenting tool to help the narrative evolve. Whereas pictorialist filmmakers position the objects and actors within the frame in a way that creates new dimensions and strengthens the narrative visually, reflecting upon the ongoing actions, showing the psychological state of the characters, foreshadowing the upcoming events, initiating subplot. For example, in Comrades (1987) Bill Douglas positions his main character within the setting in a way as if putting him in a “box” which intensifies the dilemma and shows the irremediable situation.

Figure 1.2 - B. Douglas, Comrades, 1986, Loveless in the Church, 01:08:51

The representation of space is essential for understanding a film. The arrangement and positioning of props, actors within the frame in relation with the location; the size, depth and proportions of the objects manipulated by lighting and camera’s placement and angles help convey the mood of the film and determine relationships between the elements of mise-en-scène.

Centering, balancing and frontality are used to shape the narrative, personalize the setting and help the viewer read the filmic space as a story space. Centered compositions became common in classical Western cinema of the 20th century. When framing a shot, the filmmaker places the character in the center of the composition, creating horizontal and vertical lines. Edge-framing is not common, frontally positioned figures or objects are put in the center of visual narrative, and the shot is rarely cut by either of its vertical edges. Using centralized composition, the authors of the film direct the gaze and attention of the viewer. It is hard to read a scenery as three-dimensional as we are aware of the boundaries of the image, and the vertical and horizontal lines give the image two-dimensional look. Centered compositions, still or moving, draw the concentration away from the edges and distract the spectator. With frontal positioning, both sides of the picture get in balance with one another. In a balanced composition shape, direction and location are in such a relation with each other that they seem to be mutually determined. In the classical cinema in a shot with movement, an emptiness in the frame space is reserved for the entry of a character, and the composition becomes complete and balanced after the character enters the shot.

David Bordwell (1997, p. 171) describes cinematic frontality as a powerful tool for directing the viewer’s attention within the frame. Frontality deals with the staging of elements in classical filmmaking and refers to the positioning of figures in a way that they face the camera. When filmmakers apply cinematic frontality the actor’s face “[…] is positioned in full, three-quarter, or profile view; the body typically in full or three-quarter view.” (Bordwell, 1985, p. 50). In a frontal composition the characters are arranged with the use of horizontal and diagonal lines, and people seldom close ranks as they would in real life. This approach to staging and composition is inherited from traditional Western painting and drama which hitherto inherited it from the Greek and Roman theatre and Egyptian art.

Compositions in Egyptian art are arranged by the use of vertical, horizontal and diagonal lines to maintain correct proportions. In paintings singular or grouped figures of humans or animals are presented in a two-dimensional flat space, as a composite of profile and frontal views, landscape and architectural details are sometimes overlapped and combined. An extensive number of Egyptian art display axiality and frontality. Figures and objects are presented with their most characteristic aspect and are placed on an axis, with their faces vacant of emotional expression, both shoulders front facing and one of the eyes visible. At the same time their face, waist, limbs are in profile.

The size and placement of figures in Egyptian art was determined by their importance and by the social hierarchical system, political and religious order and not based on their distance from the painter’s point of view. So the composition of the scene is designed to demonstrate the relationship of the figures and elements to each other. The Pharaoh is usually the largest figure, while the servants and animals are drawn in smaller scale, the greater gods are shown bigger than lesser gods. Important figures are presented separate from the groupings and are not drawn overlapping unlike the servants.

In art history frontality has been used in different cultures, from China to Syrian-Mesopotamian desert area, from Byzantium to Rome, developing and gaining new connotations. The artists of Renaissance inherited from their predecessors a tendency towards presenting a work of art as a unity of time, space and movement, so that a single composition shows a certain event that takes place in a particular setting at a certain moment in time (Dillenberger, 2005, p. 89).

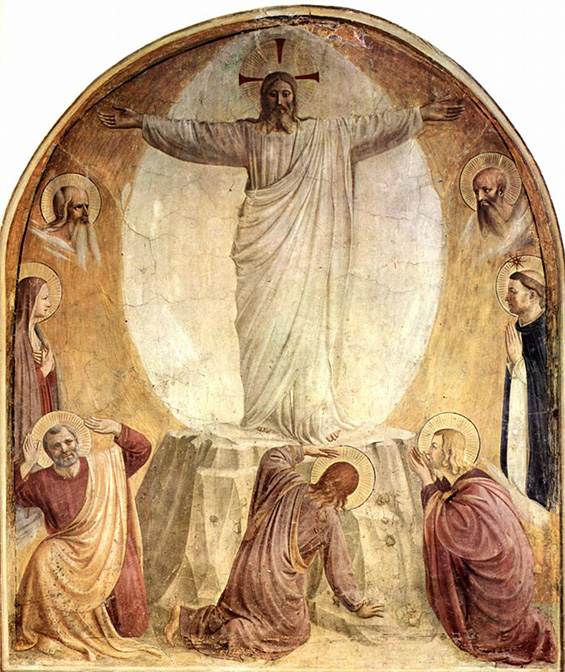

The Renaissance paintings rarely have frontal view: profane figures are usually presented in profile or three quarter-profile, while in the majority of paintings of the same era frontality is used to represent Jesus Christ as God and the Savior (Christ as the Sufferer and the man of Sorrows is usually shown in profile). With frontality, an all-seeing eye of the Savior follows the beholder however s/he moves and from whichever perspective s/he is looking at the Holy Face, creating an impression of Christ’s almightiness, omnipotence and omnipresence. In frontal icon the artists achieve a manifestation of the Savior’s dominance and an intensification of the dependence of the beholder with the all-seeing gaze (Kippenberg, 1990, p. 47). Though the gaze does not communicate a particular emotion.

In Transfiguration, a fresco dated to 1440-1442, Fra Angelico adds an aureole behind the Christ’s head and a white luminous cloud surrounding his body. The frontal pose of the body and the frontal position of his head give a commanding stillness and prominence to the figure and communicates a transcendental feeling. The details and features of Christ’s face are the same on both sides of the fresco, creating balance and opposing the asymmetry of the human face. This frontal stillness becomes more visible when in contrast with other apostles who are depicted ‘frozen’ in movement and are smaller in size.

Figure 1.3 - Fra Angelico. (1440-1442). Transfiguration, fresco, Basilica di San Marco (Florence)

In cinema frontal positioning of objects opposes to oblique staging which is the diagonal arrangement of figures along axes that are oblique to the camera’s lens (Bordwell, 1997, p. 168). With the use of frontality filmmakers play with the space, challenging the interval between the audience and the screen. Rudolf Arnheim argues that frontality is a structurally simple spatial orientation unlike an oblique staging which enlists the third dimension (1974, p. 261). This way of staging can increase the film’s expressiveness: filmmakers sometimes have their characters look directly into the camera, and through it right at the viewer, creating an impression that they are aware of the spectator’s presence. With the actors directly facing the camera, the frontal staging disrupts the illusion of separate universes, breaking the boundary between the audience and the screen, helping the viewer connect with the characters and get a deeper engagement with the story.

With frontality the viewer watches the characters as if through the eyes of another character. Some films may go even further and have the characters speak to the audience (direct address), e.g. Two or Three Things I know about Her (Godard, 1967), Annie Hall (Allen, 1977), Fight Club (Fincher, 1999).

Filmmakers use frontal representation, direct gaze towards the beholder and direct address to guide the viewer’s attention within the cinematic space. They can apply it to attach positive attributes to the frontally depicted figure, to create an impression of almightiness, show the social hierarchy of the characters, and play with the emotional perceptions of the spectator.

Chapter 2: Soviet Avant-garde Cinema and Sergei Parajanov

Cinema of the first half of the 20th century was developed based on the ideas of speed. To be contemporary was to use the latest media technologies, and to be fast and immediate. And although these qualities became central to entertainment, speed lost its artistic importance. And as a counterpoint to the dominant popular culture, some filmmakers created images that challenged the conventional beliefs towards the cinema regarding the content and the style of the moving images. The films that opposed to the mainstream narrative cinema, David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson, call experimental or avant-garde (2008, p. 673-675). In their book Film Art they assert that avant-garde films are created for several purposes: to express personal experiences and viewpoints (Su Friedrich), to convey a specific mood or a physical quality (Maya Deren), to explore new possibilities and experiment with the medium itself (Stan Brakhage), to create new story worlds and challenge the classical narrative (Michelangelo Antonioni, Andrei Tarkovsky).

Each period of the 20th century was characterized by distinct cinematic aesthetics that echoed the cultural and political mood of the era. The viewers can speculate on history through the way the filmmakers used and changed their visual and aural approaches.

During the 2nd half of the 20th century many nations that were part of the USSR began producing films with national elements, exploring local history, folklore, faith and traditions. The protagonists of the stories were not only soldiers and party heroes, but village workers, lost humans, the narrative did not depict a glorification of the government, but showed the human cost of the 2nd World War, followed the working class in their everyday life in despair, trying to overcome the consequences of the war. These films were often a product of regional Soviet states and were not produced by Mosfilm. The new avant-garde was characterized by long takes, still camera shots, frontal constructions (e.g. Walking the Streets of Moscow (Daneliya, 1964)). In 1962 Andrei Tarkovsky made Ivan’s Childhood that presents the story of an orphan who lost both of his parents to war. Several films were made in other languages (not Russian), for example, Sergei Parajanov’s Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1965) was produced in Ukrainian. Since then this tendency of filmmakers to feature and emphasize ethnic elements was seen as a nationalistic act, resistance to the aesthetics approved by the Soviet regime. After the release of Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, Parajanov’s applications to direct new projects got rejected for the subsequent four years, Andrei Rublev (Tarkovsky, 1966) got a green light for distribution outside the Soviet Union only in 1973, The Colour of Pomegranates was never shown in its original version as it got approved for screening only after it had scenes deleted (Ponomarenko’s cut), while got recut promptly after its limited first release in Armenia (Yutkevich’s cut).

And yet, the national policies of the central government and the local politics of the individual republics were not mirroring each other when it came to the multi-national Soviet film industry. So, although Parajanov was blacklisted in Ukraine, he got a chance to make a film in Soviet Armenia. Hayfilm (Armenfilm) in Yerevan had a project Sayat-Nova (The Colour of Pomegranate’s original name) that was supposed to present the Armenian culture, and the studio decided to offer the project to Parajanov as an Armenian who was raised in Tbilisi, Georgia just like Sayat-Nova (1712-1795) was. The director was to project the identity of the Armenian nation onto the screen, with the help of Armenian literature, painting, music, landscape, traditions and rituals (Steffen, 2013, p.116-118).

The film does not have a clearly defined plot and features almost no dialogue, it is a pictorial representation of ashugh Sayat-Nova’s world. Parajanov uses symbolism, cultural elements, textures metaphorically in order to interpret what is happening on screen. To realise his vision of the film, he creates a purely pictorial realm, exploring a visual, cinematic equivalent to literary imagery. (The Colour of Pomegranates, 2018, p. 56) As a result, knowing the story of the ashugh helps to follow the film.

Sayat Nova had a decisive role on Parajanov’s life and career, and strangely, the filmmaker’s later years can be described by the ashugh’s own poetry about himself in “My life is a mosaic window” («Աշխարհըս մե փանջարա է»). Parajanov originally wanted to establish the cinematic world as close to the life of Sayat-Nova as he could, he even separated the narrative into eight chapters with added headings that described the events of each scene and were meant to direct the audience’s attention and help to interpret the film. But this version got censored and Parajanov was instructed to remove all the references to Sayat-Nova. The 78-minute version was released to the Armenian audiences only, and later the material got recut by Sergei Yutkevich: several minutes of footage were deleted completely, some music intervals got altered, several scenes were moved to different parts, and the chapters themselves were organized differently. The 73-minute result is the version that was screened in the Soviet Union and oversees.

For the release, the title of the film gets changed to «Նռան Գույնը» (“Цвет Граната” in Russian and “The Colour of Pomegranates” in English). The controversy over the film and the bisexuality rumors resulted in Parajanov’s trial and a sentence of imprisonment for five years for pornography promotion and an alleged rape (1973). Filmmakers and artists from all over the world protested against the sentence, including Andrei Tarkovsky, Jean-Luc Godard, Michelangelo Antonioni, Luis Buñuel, Federico Fellini, but with little result. Parajanov served four years out of five in a Siberian labour camp and got released under the Brezhnev regime with the help of Sergei’s friends Louis Aragon, John Updike and Elsa Triolet. (Steffen, 2013, p. 197) After he would be prohibited to make films for the subsequent eleven years. Yet even that did not stop him from creating when in prison and afterwards, he made sculptures, paintings, collages that have found home in the Sergei Parajanov Museum in Armenia.

In 1982 Parajanov got imprisoned again, this time for less than a year. His next film Legend of Suram Fortress was released three years later. He made another feature afterwards but passed away before he could finish The Confession.

Throughout his career Sergei Parajanov made eight features and many short fiction and documentary films. Despite being prosecuted by the Soviet government, he rose to become a prominent figure in the Soviet avant-garde cinema, bringing Armenian, Georgian and Ukrainian folklore, religion and culture onto cinematic stage.

Chapter 3: World as a Mosaic: Frontality in Parajanov’s The Colour of Pomegranates

The Colour of Pomegranates (1969) is in no sense a literal biography, nor a historical film. It is rather a poetic film, created with the help of the nature and cultural elements of architecture, handicrafts, rituals, and poetry of the time. Sayat-Nova lived during the beginning of the 18th century, in times of cruelty, invasions, and yet his poetry and his songs stood still against the violence as he described and celebrated humanity, beauty and life. The same way, the film depicts the ashugh’s pictorial world: we witness mystifying rituals and strange beliefs and experience the harmonious relationship between people and nature, feelings and thoughts, colours and forms, silence and sounds. Parajanov’s interest in everyday customs, games and songs is not merely ethnographic: through folklore he wishes to communicate the moral and aesthetic atmosphere of people’s lives. The film produces a sense of the new out of a rearrangement of old and explores the inner world of Sayat-Nova through symbols drawn from the medieval Armenian culture and Apostolic Christianity. In his interview to the Soviet Screen (Советский экран) 1969, p. 184)) he mentions: “We are recounting the epoch, the people, their passions and thoughts through the conventional, but unusually precise language of things. Handicrafts, clothing, rugs, ornaments, fabrics, the furniture in their living quarters – these are the elements. From these the material look of the epoch arises.”

The Colour of Pomegranates is prominent for the way that Parajanov uses the elements of mise-en-scène and for how he brings together and positions the objects and characters within the cinematic space. The camera in the film remains still while Parajanov’s tableau-vivant comes alive with each shot resembling a medieval miniature painting. And yet, one of the most distinctive elements of the film is his use of frontality, which over time has become the emblem of his style.

There are several sources for Parajanov’s frontal technique: he derived frontality from theatre and painting, namely he used medieval Transcaucasian Miniature art as a reference to create and compose his scenes in the film. “In essence, each episode is a complete film miniature in itself, and they combine to form a single story: the living poetry embodied in Sayat-Nova.” (The Colour of Pomegranates, 2018, p. 55) Parajanov even describes each part of his literary script as a miniature.

The Colour of Pomegranates is full of frontal constructions and complete frontality. After the study of the film’s Armenian version shot by shot, I noticed that Parajanov’s use of frontality in separate scenes has different implications. So, individual scenes can be combined together based on the connotations they communicate, and each grouping can be defined by a specific expression that they convey.

According to film theorist Laura Mulvey (2006, p. 81), the stasis in film is produced by “a series of identical frames repeated in order to create an illusion of stillness to replace the illusion of movement.” Parajanov creates the impression of motion and stillness simultaneously through the use of frontality. On one hand he achieves it by putting elements and figures within the space frontally and while most of the composition is still, he adds details of motion (e.g. the shot with the rain going down the cross-stone in the monastery, while the books and the rest of the mise-en-scène are still). On the other hand, he adds complete frontality to a moving scene and creates stillness.

Figure 3.1 - Timecode: 0:07:00. Monks in the Monastery

Rather than zoom in or change focal lengths, the camera in the film is static, and people and animals move closer or further away in a two-dimensional manner. In Figure 3.1, monks are slowly approaching the pile of books in an unrealistic fashion, while Harutyun (young Sayat-Nova) stands in profile and is motionless in the right corner of the frame. And with frontal gaze to the camera, the attention is on the monks who try to dry the rainwater-soaked books by piling them up in front of the church. With the use of frontality Parajanov guides our concentration to the books and maintains stillness: the figures are moving, but because they gaze directly at the camera and their movements are slow, the audience’s attention gets distracted from the motion as they reflectively look back into the eyes of the monks. Thus, Parajanov creates an illusion of stillness through slow movement and frontality.

The Colour of Pomegranates is full of dual representations – of characters, of life and death, of faith and doubts, of sorrow and joy, of real and surreal, of violence and humanity, of sacred and profane. The filmmaker’s use of Sofiko Chiaureli to play multiple roles in the film is another demonstration of that: the actress plays the young poet, princess Ana, an angel, a nun, a white-faced mime, the Muse. And the film’s aesthetics serves to identify a network of dualities, where a scene is opposed to a scene, a shot to a shot, sound is set against sound, image against image, meaning against meaning. And Parajanov uses frontality to represent duality, express and intensify the feeling with many motifs shown under two different lights. The most striking and evident one is, perhaps, the male and female duality.

The motif is introduced in the 1st chapter and accompanies the narrative throughout the whole film. As a child, Harutyun follows how men and women work, he engages in the process of making carpets, observing how men and women are separated in the society as men make the material and threads for women to knot later. Parajanov presents the motif to the viewer by the use of frontality, showing lovers looking at one another as if in a mirror, finding in the beloved the reflection of each other’s thoughts. The director references to the 18th century Transcaucasian paintings where lovers are depicted with identical faces. This is one of the reasons young ashugh and his lover princess Ana are played by the same actress.

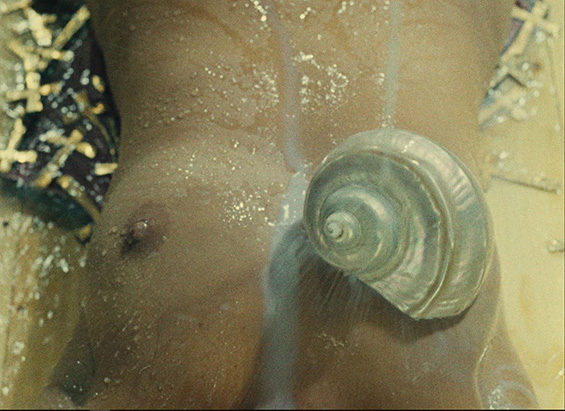

Later in the chapter young Harutyun goes to the bath and spies on naked men and then on women (Figures 3.2-3.5). Parajanov creates a series of erotic shots as men and women bathe, looking into the camera and through it at the viewer. And for the first time, he depicts the boy from the back: by rejecting frontality, Parajanov makes us wonder what young Sayat-Nova’s reaction is.

Parajanov uses several props to symbolize the female sexuality throughout the film. The bath scene represents the boy’s erotic awakening. He sees a woman’s chest and imagines it covered by a shell. It is after the bath scene that Sayat-Nova gains another persona, the Muse (Parajanov gives an implication of bisexuality), and it is not a coincidence that young Sayat-Nova and the Muse are played by the same actress.

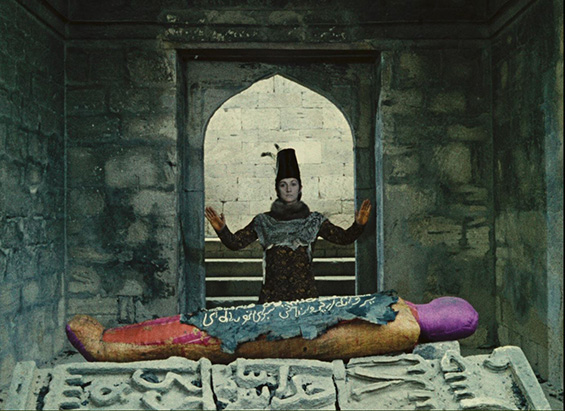

The motif of death accompanies the narrative of The Colour of Pomegranates since the opening sequence (pomegranates and knife bleeding) till the ending sequence (the poet’s death). The first time we encounter death, though, is in the scene of the tomb where a body lies in the foreground wrapped with multi-coloured cloths, and a strong wind fills the frame with dark ashes. The poet’s male and female personae are displayed merging in this scene. Afterwards, they diverge again, the Poet giving up to his sorrows and the Muse being the representation of life and free will, sensually and emotionally. In the following shots, when they come even closer to the concept of death by reading the text on the body, the representation of the characters changes. Although they are still depicted gazing directly at the camera, their bodies are not frontal anymore, as if being closer to Death changes their axis, so now instead if vertical lines, their bodies present diagonal lines. Death changes the representation of objects literally and metaphorically.

An interesting depiction of the duality of life and death can be found in the 2nd and the last chapters of The Colour of Pomegranates. Sayat-Nova in Figure 3.10 is represented in complete frontality, while the skeleton head is in profile. In the same shot the poet slowly reaches for his eyes to cover them and hide from death, while he changes the skeleton to face the camera and the audience. A similar depiction can be found in Figure 3.12 where the aged poet is not hiding his eyes from death anymore, the skeleton is turned from profile to frontal position, while the ashugh does the contrary. It is not a coincidence that the skeleton head is wearing a soldier’s helmet: Parajanov uses these shots to hint on the death of the poet by the hands of the Iranian soldiers. The filmmaker plays with frontal and in-profile representation of the main character to show the change in Sayat-Nova’s attitude towards death: in the second chapter he is not ready to face it, later, the adult poet gives a glace from the side, while in the end he is ready to encounter it (Figure 3.13).

Christianity plays a big role in the film: after the opening sequence the voice-over text tells the story of how God created humanity, while the visuals show images of cross, candles, Armenian cross-stones and monasteries. Parajanov uses miniature art as a reference in his film as Sayat-Nova himself encountered the art and lived surrounded by it, after he became a priest. So the use of miniatures is a measured addition to stylistically complete the character’s journey.

Parajanov uses complete frontality and presents Sayat-Nova and princess Ana: they look into the camera and through it at the audience with the all-knowing gaze. In ancient icons, the same saint is depicted with different faces, and Parajanov uses frontality to show the poet as a divine figure, even though he is still an ashugh living in sin (his affair with princess Ana) who celebrates life with his songs and poetry (Figures 3.14, 3.15). His Sayat-Nova is in doubts, living between the struggle of sacred and mundane impulses. It is later that the poet decides to become a priest and reject the joys of life.

Parajanov uses iconography as a reference to present the parents of Sayat-Nova in the last chapter of the film as well. As the poet is close to his death, he imagines them in after life, saint-like, surrounded by angels and with Harutyun sitting next to them. Parajanov uses frontality to depict them and adds a nimbus surrounding their heads, presenting them through the eyes of Sayat-Nova, and gives more prominence to the characters of the parents by the end of the film.

Parajanov systematized his tableaux procedure into a form that is static with the use of appearances and disappearances or transformation of objects within the mise-en-scène. (Martin, 2007). The first time Parajanov introduces us to the main character, Harutyun as a child, he depicts him in complete frontality, kneeling down to the ground in fetal posture, innocent. And every chapter of the film starts and ends either with Harutyun or Sayat-Nova gazing directly into the camera or with still life objects placed frontally in the frame, creating horizontal and vertical lines.

In the end of the 1st chapter, Parajanov uses frontality to present the transformation of Harutyun into Sayat-Nova. The movement in the scene is theatrical as the boy slowly walks behind the figure on the left and hugs him from the back, merging with his adult self. The figure holds a kemenche in his hands: the innocent child has grown into an ashugh.

Parajanov uses frontality as an implication of change and a symbol of transformation in a number of scenes in the film, for instance, when his parents are back in the graveyard scene wearing black as the strong wind blows, ending of the third chapter, the scene where he leaves the palace.

Parajanov creates an uneasy feeling by using averted or profile gazes that transform into complete frontality. In the 1st chapter of The Colour of Pomegranates the monastery scene depicts three monks slowly climbing the stairs and looking directly at the camera, while another monk is in profile on his knees on the right side of the composition. As the three monks are in motion and are depicted frontally, they are also in the center of our attention when suddenly Parajanov shifts the concentration on the monk in profile, as he moves his head to face the camera.

When Sayat-Nova is at the funeral, a pair of angels guide a man whose eyes are blindfolded. They take the soil wrapped in lavash from him and give it to Sayat-Nova. The next shot features a window with the angels looking at the viewer through it. “Աշխարհըս մէ փանջարա է,” says the voice-over text citing the poetry of Sayat-Nova (Փանջարա has two possible connotations - a mosaic and a window, and Parajanov creates a window, surrounded by a glass mosaic) (Figures 3.18-3.21). And the ashugh could see through that window to God, to the transcendence leading a life between spirituality and mundanity. With the use of frontality Parajanov makes the viewer feel like they are looking into the character’s eyes – the window, giving the spectator a chance to see through the flesh of Sayat-Nova into his world and pass beyond the sufferings and pain to find purity, love, and get closer to the transcendence.

Conclusion

Cinema is connected to the traditional visual art forms with the use of compositional elements, movement and stillness, and with pictorialism, which also links it to literature. Thus, films can be analysed in relation to painting, architecture, theatre, photography, literary writings and performance art as all artists deal with objects, characters, movement, space and time. Pictorialism can be described as a cinematic tableau that brings together different art forms.

The Colour of Pomegranates is an example of pictorial cinema where Sergei Parajanov uses space and creates compositions in a compelling way. The film is among the most challenging feature films produced in the Soviet Union. Parajanov uses many techniques and stylistic elements when approaching the cinematic space. He applies symbols, metaphors, rhythmic repetitions of visuals and sound, compositions derived from Transcaucasian Miniature art, that echoes throughout the film, unifying the visual style of the eight chapters. And yet, if there is one technique that characterizes his work and style, it is frontality.

Directors guide the viewer’s attention within the frame with the frontal representation of objects and characters and with the use of direct gaze into the camera. The Colour of Pomegranates (1969) is a multi-faceted work where Sergei Parajanov presents frontality from a mosaic of perspectives and uses it in abundance, so that it’s easier to count the shots without frontal representation rather than with it. He applies it as an expression of stillness, as a representation of duality, as a way of idealization of the characters, as a symbol of transformation and as a means to draw attention. So, each shot with frontality can be described as conveying one or several of the five implications.

Sayat-Nova famously said: “Աշխարհըս մէ փանջարա է 1,” and in The Colour of Pomegranates Parajanov brings the cultural pieces of mosaic together to construct a window and transfer the story of the ashugh on-screen. With the use of frontality he creates an impression that the viewer is looking through the window at Sayat-Nova’s poetic world, observing his feelings, inner conflicts and dilemmas, his love for life and humanity.

Notes

1Armenian for: “My life is a mosaic, a window.”

Filmography

Douglas, B. (Director). 1987. Comrades. UK: Skreba Films.

Parajanov, S. (Director). 1969. The Colour of Pomegranates. USSR: Armenfilm.

Art References

Caspar David Friedrich. (1808-1810). The Monk by the Sea, oil painting, Alte Nationalgalerie (Berlin). Retrived from: https://bit.ly/2YvQrf5

Fra Angelico. (1440-1442). Transfiguration, fresco, Basilica di San Marco (Florence). Retrived from: https://bit.ly/2vUJkjO

Bibliography

Arnheim, R. 1974. Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye. (2nd ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Bordwell, D. 1985. Narration in the Fiction Film. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Bordwell, D. 1997. On the History of Film Style. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bordwell, D. & Thompson, K. 2008. Film Art. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Brewster, B. & Jacobs, L. 1997. Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Dillenberger, J. 2005. Style and Content in Christian Art. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers.

Groys, B. 2011. The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond. (Rougle, C. Trans.). London, UK: Verso

Hagstrum, J. H. 1958. The Sister Arts: The Tradition of Literary Pictorialism and English Poetry from Dryden to Gray. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kippenberg H.G., van den Bosch L.P., Leertouwer, L. & Witte H.A. (Ed.). 1990. Visible Religion: Genres in Visual Representations. (Vol. 7). Leiden, the Netherlands: State University Groningen Press.

Lavey, N. 2016. Introduction to Film. (2nd ed.). London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lessing, G. E. 1984. Laocoön. (McCormick, E.A. Trans.). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Martin, A. 2007. Parajanov and Frontality. Retrived from: http://www.filmcritic.com.au/essays/parajanov.html

Melbye, D. 2010. Landscape Allegory in Cinema: From Wilderness to Wasteland. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Metz, C. 1974. Language and Cinema. (Umiker-Sebeok, D.J. Trans.). Plano, TX: The Hague Mouton.

Metz, C. 1986. The Imaginary Signifier: Psychoanalysis and the Cinema. (Britton C. & Williams A. Trans.). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Morgan, D. 2012. The Embodied Eye. Religious Visual Culture and the Social Life of Feeling. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Mulvey, L. 2006. Death 24x a Second. Stillness and the Moving Image. London, UK: Reaktion Books.

Nietzsche, F. 1968. Twilight of the Idols and The Anti-Christ. London, UK: Penguin Books.

Parajanov, S. 2001. Исповедь (Confession). Moscow, Russia: Azbuka.

Pearce, R. 1983. The Novel in Motion: An Approach to Modern Fiction. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press.

Rothman, W. & Keane, M. 2000. Reading Cavell’s ‘The World Viewed’: A Philosophical Perspective on Film. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press.

Sayat-Nova: Tsar. 1969. Советский экран (Soviet Screen), pp. 183-185

Steffen, J. 2013. The Cinema of Sergei Parajanov. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Tashiro, C. 1996. When History Films (Try to) Become Paintings. Cinema Journal. 3rd ed. 19-33. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

The Colour of Pomegranates. 2018. Criterion Collection. London, UK: Second Sight Films.

Tretyakov, S. 1928. Наше Кино (Our Cinema), pp. 30-33.

Valkola, J. 2016. Pictorialism in Cinema. Creating New Narrative Challenges. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Winner, V. 1970. Henry James and the Visual Arts. Charlottesville, VA: The University of Virginia Press.

Wolf, N. 2003. Caspar David Friedrich: 1774-1840: The Painter of Stillness. Köln, Germany: Taschen.

Zabel, G. 1993. Marxism and Film. Chicago, IL. George’s Hill Publications.