Abstract

To the often-studied relationship between dance and cinema, kindred arts of the moving body-moving image, I propose to add an original analysis of the relationship between the sub-genres of historical dance (in particular the social and theatrical dances of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries) and period cinema. To that end, it is not only important to question the extent to which dance is merely illustrative, or serves as a narrative instrument in this type of films, but also how period cinema contributes to the construction of a historical memory of dance.

There are several contexts that justify the introduction of a staged dance on film and they depend on a number of choices on the part of the artistic team. In period cinema these choices are particularly delicate, especially when the “world of the play” is relatively unconcerned with historical accuracy. Based on a selection of films including Valmont (1989), by Milos Forman, Jefferson in Paris (1995), by James Ivory, Le Roi danse (1999), by Gérard Corbiau, Marie Antoinette (2006), by Sofia Coppola, and Alan Rickman’s A Little Chaos (2014), I analyse the criteria for the introduction of dance scenes, and reflect not only on their aesthetic and metaphorical effects, but also on their power of transmission, as well as of (de)construction, of a stereotype of historical dance.

Keywords: Baroque Dance, Historical Costume Drama/Period Films, Choreography, (Re)Creation, Artistic Creativity

A brief introduction to dance on screen

From the earliest days of experimentation in film technology, from Annabelle’s Butterfly Dance, filmed between 1894 and 1896 by the Edison Manufacturing Company, and which depicted Loïe Fuller’s serpentine dance, to David Griffith’s Intolerance (1916), dance and cinema have been closely intertwined, exerting a potent influence on one another. On the one hand, we have the introduction of frames and camera movements specifically intended to capture the choreography, and on the other is the choreography itself that is magnified, becomes more elaborate, and with greater attention to detail in accordance with the way it is filmed. The 1920s witnessed the rise of the genre par excellence in the relationship between dance and cinema, the musical, which has its golden years in the period 1930-1940. A distinction is also made here between two types of use of dance: the backstage musical, in which the choreographed scene adds nothing to the narrative, working against the flow of the story being told, and in which the frontal point of view is frequently abandoned for the exploration of perspectives and spaces only possible thanks to the technology of cinema; and the integrated musical, in which dance is given an essential role in the narrative, based on an accord between storyline and choreography. In general, it was the latter type of deployment of dance that was developing and assuming different contours throughout the history of the cinema and up to the present time. Of course, not all the films that contain dance scenes belong to the category of musicals. Thus, the contexts that justify the introduction of a dance scene on film are varied and depend on a series of choices by the artistic team: the creation of a scene that calls for it in the narrative; the type of dance and music; the suitability of the scenery and costumes; the choice of characters and consequent choice of performers (actors versus dancers); which part of the dance to show, how much of it, and how, among other issues. In period films these choices are particularly delicate, considering the usual constraints attendant on narrating a story set in a given historical period.

A selection of period films

Since I am interested in studying how the social and theatrical dances of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries are portrayed in cinema, the scope of my analysis is necessarily limited to period films. The selection was narrowed down to a total of eight films1: Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975); Milos Forman’s Valmont (1989); James Ivory’s Jefferson in Paris (1995); Véra Belmont’s Marquise (1997); Gérard Corbiau’s Le Roi danse (1999); Roland Joffé’s Vatel (2000); Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette (2006); and A Little Chaos (2014), by Alan Rickman.

With the exception of Barry Lyndon, all the selected films are set in France, and, excluding Valmont, Jefferson in Paris, and Marie Antoinette, which take place at the court of Louis XVI, all others are set at the court of Louis XIV. This coincidence of historical contexts is not surprising, and points to what Genevieve Sellier has identified as a sub-genre:

Les diverses péripéties du règne de Louis XIV paraissent une source inépuisable d’inspiration pour le cinéma français, à tel point qu’on peut y voir un véritable sous-genre du film historique, qui semble jouir d’une nouvelle faveur depuis les années 1990. (Sellier 2002, 395)2

It therefore seems almost impossible to remove ourselves from the French court if we are looking for this type of historical dance—the French court dances of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, la belle danse, or baroque dance as it is generically known in dance historiography, and which reached its performative, social, and political apogee, and, importantly, was constituted as an academic discipline (with the formation of the Académie royale de danse, and the creation of a system of choreographic notation and teaching method), during the reign of Louis XIV, and under the direct stimulus of this monarch.3 There is, therefore, a predilection for themes related to French social, cultural, and political history, although the practice of dance was common to Europe in general and the European colonies, as well as social circles beyond the court.

Within this scope, a common theme in several of these films is the confrontation between the “nobility of blood” and the “nobility of virtue”, inspired by events and personalities drawn from the historical narrative of French cultural superiority. (Sellier 2002, Shapiro 2005) Several historical artists are thus found as protagonists, which in most cases partly serves to justify the use of dance scenes: Marquise tells the story of a street dancer (a character loosely based on the actress Marquise du Parc) who rises at court by performing in plays by Molière and Racine, her co-protagonists; Le Roi danse once again features Molière (although the dance master Pierre Beauchamps also makes a brief appearance), but the spotlight is on the relationship between the composer Jean-Baptiste Lully and the Sun King, who depend on each other for the assertion of their social/political roles; Vatel is the name of the master of ceremonies and cook who becomes both the hero and the victim of the festivities organized by the Prince of Condé in honour of Louis XIV; and, finally, A Little Chaos gives us a glimpse into the work of landscape painters André Le Nôtre and Sabine de Barra (fictional character) at Versailles.

Historical period film generally speaking requires, besides the choice of an era, a place, historical characters, facts, or contexts, worked into an original or adapted story (only Barry Lyndon, Valmont and Le Roi danse are adaptations, the first of a homonymous novel by William Makepeace Thackeray, the second, of the epistolary novel, Les Liaisons dangereuses by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, while the last is based on a biography of Lully by Philippe Beaussant), choices related to scenery, wardrobe, props, and lighting, for example, which are essential to the creation of the “world of the play”: “More important than the actual historical period […] is what directors and designers refer to as the world of the play” (Alberts 1997, 131).

For the analysis undertaken here, I also look at the role of historical consultants and of choreographers and/or movement coaches, all of which, if absent, may ruin the credibility of a scene—but I return to this issue below. All the films, with the exception of Marquise and A Little Chaos, made use of a historical consultant, and all the directors, without exception, worked with choreographers for the dance scenes: Geraldine Stephenson in Barry Lyndon; Ann Jacoby in Valmont; Béatrice Massin in Jefferson in Paris and Le Roi danse; Corinne Devaux in Marquise, Vatel, and Marie Antoinette; and Jane Gibson in A Little Chaos. As for the performers, almost all the films include dance sequences that, however brief and secondary to the plot they may be, are executed by professional dancers. Yet in only two of them, those choreographed by Béatrice Massin, these artists appear in the closing credits.

What is the role of historical dance in period cinema?

In order to begin answering the first question posed by the title of this paper, let us now turn to the dance scenes themselves—when and why are they inserted?

There are four main contexts in which dance scenes appear: private dance moments, dance balls, entertainments, and rehearsals for the latter. Basically, if we set aside dance lessons involving master and student, these are the possible instances for the practice of dance and, in the case of baroque dance, also the contexts that allow us to single out the two styles within the genre, the social dance and theatrical dance, which differ mainly in technical complexity, as well as more obviously in terms of space, costumes, and props.

Only in Valmont do we find two private dance scenes, that is, dance practices that are not part of a public occasion, and do not follow a pre-defined code or etiquette, taking place in the more intimate space of a private home. Both take place inside the property of Madame de Rosemonde, the protagonist’s aunt, and are composed of couples dances: the first in the gardens, involving Valmont and the object of his desire, Madame de Tourvel; and the second in the parlour or sitting room, at night, involving Valmont and four of the main female characters in the film, the aunt, Madame de Tourvel, Marquise de Merteuil, Valmont’s former lover and instigator of the revenge plan that aims to make use of the young Cécile de Volanges, the other female figure in the scene. In a film whose plot revolves around sexual manipulation and seduction as weapons of social domination, and is a tragicomic portrait of the moral decadence of Ancien Régime aristocracy, dance creates the opportunity for moments of gallantry between individuals embroiled in the various love triangles. The second scene, the evening dance, makes very intelligent use of the different forms of social dances: for each couple a different dance is chosen, corresponding to each one of Valmont’s female dance partners and the relationship they have with him. The minuet, a dance that had already been chosen for the first scene, in the gardens, features again on this evening. This dance was the foremost of the social dances from the middle of the seventeenth and through the eighteenth century. It was considered the noble dance par excellence, and thus a logical choice for the most mature female characters, Madame de Rosemonde and the Marquise de Merteuil, placing the latter alongside the aunt, not without a certain irony. With Cécile de Volanges, Valmont dances a jig, a joyful, jovial, and fast-paced dance, perfect for depicting a playful and disinterested relationship between Valmont and this fifteen-year-old girl. The dance with Madame de Torvel, meanwhile, is much more ardent and intense, which helps reveal that this character is about to succumb to Valmont’s charms. It is a bourrée, normally a light and graceful dance, here deliberately slowed down, and choreographed in an anachronistically romantic style. In a single scene around three minutes long, without words and with only a few steps and movements from four different dances, Milos Forman condenses the whole story of the film, summarizing Valmont’s relations with each of these women, quite different in nature.

There is no need here for a detailed analysis of the choreography and choice of steps and figures, or the choice of musical repertoire and its rendering. It is more interesting to emphasize that this scene perfectly exemplifies the salon culture of the late eighteenth century aristocracy, and their knowledge of the most fashionable choreographies, which circulated among these social groups. This work reveals a profound knowledge of early dance. Choreographer Ann Jacoby was one of the founders of the New York Baroque Dance Company (1976), along with Catherine Turocy, the Artistic Director. This company is among those mostly responsible for the diffusion of the study and practice of the baroque dance in the US, in way that combines both academic research and performance. Ann Jacoby, like Béatrice Massin, as shown below, was for most of her career a “scholar-performer”, which makes all the difference in her contribution to the production of this film.

Three different types of formal dance or ball feature in the chosen films: the popular dance in Barry Lyndon; the court ball in Marie Antoinette and A Little Chaos; and the public ball also in Marie Antoinette.

Stanley Kubrick’s film is the only one to feature a traditional dance, the Irish gig—which also belongs to the repertoire of social dances of this period—and which is danced freely in the field among the common people and the soldiers and officers of Captain Quinn’s regiment, in celebration of the latter’s arrival in Redmond Barry’s village (in the midst of the Seven Years’ War). The dance turns out to be the beginning of all the protagonist’s misfortunes, for it is during the dance that Nora Brady, his beloved, gets to know and falls for the Captain of the regiment, dancing with him under Redmond’s jealous gaze. Asked by her cousin about her interest in the officer, Nora responds “he dances prettily to be sure, and is a pleasant rattle of a man.” Ariane Hudelet’s analysis of the dance scenes in the television and film adaptations of Jane Austen’s novels applies just as well to this film:

Lorsque le cinéma et la télévision adaptent ces romans (ce qui est fréquent depuis 1995), ils choisissent souvent de donner une place importante à ces scènes [de dança] qui permettent d’exprimer les relations entre les personnages, et les éventuelles tensions entre aspirations personnelles et contraintes sociales, non seulement par les dialogues mais aussi et avant tout par le mouvement de la danse, qui se prête très bien à une représentation audiovisuelle. (Hudelet 2006, 415)

During this period, the ball was the privileged moment of conviviality between the sexes. All dance and conduct manuals, which were popular at the time among the lesser nobility and the bourgeoisie, described in detail the dance etiquette and the rules of decorum in relations between ladies and gentlemen.4 Naturally, a provincial dance in the open air, as a somewhat improvised expression of delight at having a regiment passing through the region, may have taken place just as directed and filmed. The role of the dance scene in the unfolding of the plot is the work of the novelist, Makepeace Thackerey; but the decision to honour this moment and to give a visual representation of gallantry between the future couple Nora and Quinn, and of Redmond’s jealousy and sense of betrayal, almost without having to resort to dialogue, is that of the screenwriter and director Stanley Kubrick.

The manuals that I have referred to, as well as other sources from the time (correspondence, memoirs, engravings, among others), always present the royal ball or the court dance as a model. It is possible to find several descriptions of the etiquette to be observed, as well as engravings that purport to depict a particular dance as it was performed (or what it should have looked like). In these documents we find figures represented hierarchically and carefully distributed in space, the dancing couple assigned a central position, in a way that makes them the focus of all the rest. We also know that the ball always took place as part of the festivities celebrating important events in the life of the royal family, such as birthdays, baptisms, and weddings.

Indeed, the first dance scene in Marie Antoinette, choreographed for a couple, is intended to represent a royal ball, part of the program of the marriage celebrations of the future king Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette. Most probably the bride and groom’s dance shown would have been the opening dance of the ball—the ceremonies are in their honour and the music we hear is a minuet (the 1st minuet of Les Indes Galantes by Jean-Philippe Rameau), which, together with the courante, were the usual opening dances of the ball. However, the film does not allow this scene to unfold any further, that is, it does not follow the ball.

On first appraisal, the introduction of this scene in the film only seems to illustrate the elaborate festive apparatus of the Versailles court, in common with other scenes of great visual impact. However, the two minutes’ duration of this moment (the dance is shown from beginning to end) are open to many more possible readings. On the one hand, following the idea developed above that the dance is a rare opportunity for conviviality and physical proximity between the two sexes, the Dauphin’s intense discomfort is evident, in contrast to his bride’s greater ease of movement, as if giving proof of her ability to fulfil her role at court. On the other hand, screenwriter and director Sofia Coppola opted not to follow the spatial etiquette of that type of ball. Rather, she decides to film the couple appearing through a crowd that watches them with a mien befitting birds of prey, and perform their dance in a very confined circle. This feeling of suffocating display and judgement to which the future royal couple are exposed, and the metaphorical image of hunter-prey, is constant throughout the film.

Figure 1 – “Le grand bal du Roy” in Pierre Rameau’s dance manual Le maître à danser (1st edition 1725). (Rameau 1748, 53)

Figure 2 – The weeding dance scene. (Coppola 2006)

As far as choreography is concerned, Corinne Devaux is not a specialist in this historical genre. She has extensive experience as choreographer for films set in different periods and styles—and perhaps this explains her being given the job of choreographer in three of the films under study. However, she does not completely master the technique of baroque dance, opting for something that is always a kind of approximation (or, to venture a personal opinion, a simulation that almost succeeds). To be sure, there are no egregious choreographical errors—included are the curtsies at the beginning and at the end, either to the king or between the couple (albeit in a somewhat adulterated style) and steps that seem, whenever there are close-ups, executed in a manner that is not anachronistic. However, it is not a choreography for minuet, the accompanying music in the scene, which has its own almost obligatory steps and dance patterns, some of which, like the leaps performed by the protagonist at a given moment, are not consistent with this type of ball or formal dance, or even with the kind of elaborate dress worn by Marie Antoinette. There is, of course, room for artistic freedom. However, despite the contemporary approach intended by the director, here she seems to be aiming for a historically faithful representation of this dance—contrary to what we see in the later scene of the masked ball—and thus the small incongruities pointed out above seem to be rather due to the choreographer’s lack of knowledge or concern for verisimilitude than poetic license.

The second dance scene in this film features a masked ball in Paris, outside the controlled space of the Versailles court, which the royal couple attend incognito with a group of their closest courtiers. Once again, the use of the dance is a pretext for the intermingling of men and women—it is in this scene that Marie Antoinette meets her future lover, Count Fersen. The dance aims to recreate or imagine the atmosphere of a public dance where preference would be given to countrydances, more convivial and relaxed in style, and relatively unburdened by the rigours of social etiquette. What we see in this scene is a group dance, lively, frenetic, and full of spinning and whirling (although it is not a complex dance, the performers are clearly professional dancers, given the synchrony and precision of their movements, although uncredited in the film) meant to resemble a countrydance, but with clearly implied transgressive potential. The music we hear is Siouxsie & the Banshees’ “Hong Kong Garden”, a modern expression of that festive mood, and both the use of an aerial perspective, which highlights the choreographed circular movements and the exuberant commotion in space, as well as a Steadicam, which accompanies the actors trying to make their way between the dancing couples, contribute to the sense of an environment of unfettered freedom and youthful gaiety. This dance not only serves to introduce a new central character, but represents an escape for the protagonist, a metaphorical flight of the caged prey.

The last dance scene in my selection of films appears in Alan Rickman’s A Little Chaos. However, due to some liberties taken in this film,5 this scene is somewhat ambiguous, it being unclear whether it is a dance, or a staged entertainment… or if that was of any particular concern to the director and choreographer.

As already mentioned, any court ceremony, particularly at the court of Louis XIV, was carefully staged according to a code of conduct that emphasized social hierarchies and personal distinctions. This is, moreover, and as we have already seen, a characteristic of the time that contributes to plot development in this genre of films. It is the basis for a particular sense of decorum and the importance of cultivating appearances. The plot of this film is grounded in these presuppositions and thus draws attention to two specific themes: the romantic relationship between Madame de Barra and André Le Nôtre, and the merits of the “nobility of virtue”. The scene is conceived and staged with these in mind.

It should be stressed that this is the film’s final scene, the scene that confirms the “happy ending” and assures us of the restored harmony and the success of Madame de Barra’s work with the inauguration of the Bosquet des Rocailles. Dance is often used for its symbolic power to restore order, and in this respect it is wholly consistent with the spirit of the age. Apart from this aspect, everything else is lacking in historical and/or artistic basis. The intention is to make believe that the dance is improvised, because the inauguration festivities at the Bosquet are supposed to be a surprise for the king—the orchestra is even hidden behind the waterfall, in the bushes, with musicians seated on fallen tree trunks (!) … How could one hear the music “ambushed” like this? Why not have the orchestra on site, since the space was after all built in the form of an amphitheatre for the performance of dances (hence also being known as the Bosquet de la Salle du Bal)? It may be irrelevant to the film, relying on a suspension of disbelief, since the music one hears is extra-diegetic. The choreographed segment begins as a dance of Louis XIV and Madame de Barra, only for the protagonist to leave the scene a few steps in, to get ready for the planned final kiss with her co-protagonist (as the saying goes, “only in Hollywood!” would this monarch dance with a commoner, who then abandons him in the middle of the dance). The scene continues, with the choreography becoming somewhat more theatrical, the remaining pairs of dancers standing around the monarch, who is at the centre of the space, in a clear allusion to the political metaphor of the Sun King—here assuming a wholly benevolent posture.

The choreographer, Jane Gibson, has extensive experience as choreographer and movement and behaviour coach/etiquette advisor.6 In this film, she is only listed as a choreographer—this work on movement and etiquette with the bulk of the actors and extras is somewhat lacking in my opinion; for instance, in this last scene some courtiers are seen climbing the garden benches in a less than orderly and rather inelegant manner, with the ladies’ skirts pulled up to their knees. Gesture and movement are part of the construction of a period character. The dance, by itself, does not transform the body of the actors. Finally, from the technical standpoint, the dance betrays the choreographer’s forte: the English countrydances of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It suffices to observe the movement of couples in a grand chain crossing, in pas-de-bourrée—a figure typical of the countrydances, but not of the French court dances, and therefore ill fitting.

The remaining films (Jefferson in Paris, Marquise, Le Roi danse and Vatel) foreground the performative aspect of the dance, showing the rehearsal and/or performance of theatrical dances. It should be noted that the decision to show the rehearsal for the performance, which takes place in Le Roi danse and Vatel, works as a mise en abyme, in which the art of cinema shows the work of preparation for the theatrical entertainment, which is subsequently also seen. This decision, which is only justified if it fits into the story, guarantees a more consistent integration of the dance within the film—by contrast, one might single out A Little Chaos once again: why and how would the gardener/landscaper Madame de Barra know what to dance in that final scene, and so spontaneously?

However, instead of analysing the scenes in these films by taking into account their narrative contexts, as I have done above, I will group them by choreographers: first, Marquise and Vatel, choreographed by Corinne Devaux, followed by Jefferson in Paris and Le Roi danse by Béatrice Massin.

In Marquise, the protagonist is a naturally gifted dancer, a character loosely based on Marquise du Parc, who becomes first a dancer and then an actress in the company of Molière, enabling her social ascent—from a stage in the middle of the street, to the public theatres and, finally, to the theatres of the court, in Molière’s comédie-ballets. By the end of the film she finally attains the status of actress and makes her debut (though the role proves too much in the end) in Andromache, a tragedy that Racine, her lover, is meant to have written for her. However, her dance style remains unchanged throughout the film, ‘popular’ and sensual in nature, and even the choreography is virtually the same in the three different dance scenes shown in the film. The most representative and repeated steps, which the camera focuses on, whether in aerial perspective, wide shots, or slow motion, are turns, rhythmic beats with the feet and hands, back-twists, cartwheels with legs in the air, pirouettes and leaps—the main purpose being to show them as cheerful dances that expose the body of the protagonist.

For any historical epoch, it is always more difficult to study its popular dances than the cultivated dances of the social elite, due to the lack of sources. Corinne Devaux, a choreographer in dozens of films, despite not being a specialist in this type of dance, adapts the style and technique of the choreography to the context required by the director, combining popular elements with steps drawn from classical dance and some aspects of baroque gesture. This methodology is also evident in Vatel.

The plot of Roland Joffé’s film takes place over the three days (plus the day before) of Louis XIV’s visit to the Prince of Condé at the Château de Chantilly. For each of the days there is a different program of festivities, including dance, music, singing, fireworks, all within elaborate theatrical productions using intricate stage machinery. However, despite the centrality and visibility that is given to baroque spectacle, it only functions as a backdrop. The four scenes that feature dancing (two shows, one rehearsal, and one ball) are only illustrative and always curtailed—in the ball scene, incidentally, the dancing is not even the focus, but is merely glimpsed in the bottom of the frame, through an open door. Thus, in this case one cannot properly speak of dance choreography, for one is only allowed to perceive some movements, gestures, and positions, which, once again not being drawn from the vocabulary of baroque dances, do not conflict with the film’s purpose—on the contrary. All the other elements of the artistic production of these scenes, that is, the scenery, costumes, props, and apparatus, are quite consistent with the film’s “world of the play.”

For the final part of this analysis I turn to the two films choreographed by Béatrice Massin, a French specialist in baroque dance. In Jefferson in Paris, we find the dance embedded within an opera, Dardanus, a tragédie lyrique by Antonio Sacchini, which was indeed staged at the Paris Opera in 1784, just as shown in the James Ivory film. The dance choreography is not foregrounded, but invariably overlaid by another element, more distracting or prominent, whether it is the disorderly crowd in the stalls, or the singer being lowered onto the stage by means of theatrical machinery. However, two couples are observed on stage, performing specific baroque dance steps (such as a pas-de-bourrée vite).7 It should be noted, on the one hand, that opera performances in public theatres at the end of the eighteenth century were very popular and also provided an opportunity for non-courtier social groups to attend such events (this opera was first staged at court in Versailles), and, on the other hand, that this was, once again, an occasion for the intermingling of the sexes. Thus, this scene creates the opportunity for the reunion of Thomas Jefferson and Maria Cosway, as well as for the protagonist to make his declaration of love. For the director, the aesthetic power of the scene alone is sufficient justification:

They’re not there to “liven up” the story as such or to add interest that the story may lack. I don’t see why they can’t be enjoyed for what they are. The opera scene in Jefferson in Paris is beautiful in itself. The music was wonderful and probably hadn’t been performed since Jefferson’s day. The whole atmosphere we created was probably something that nobody had ever seen in a movie—that kind of confused circus atmosphere of the eighteenth-century Parisian theater. That was a new thing. (Long 2005)

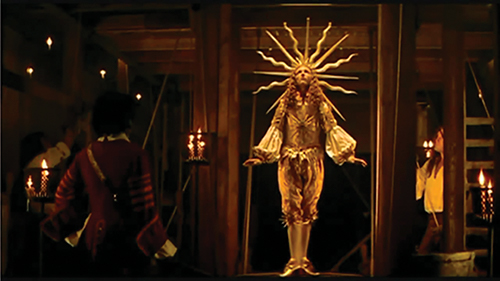

Le Roi Danse is a film unlike any other, in the sense that dance plays a central role in the narrative, which is made explicit in the title. The dance, through the creations of Lully, Molière, and Beauchamps (although, strangely, the court dance master appears only as an extra in one of the scenes, played by one of the dancers, Jean-Marc Piquemal, who was also the choreographer’s assistant in the production of the film), allows Louis XIV to assert his sovereignty and the language of power before the other political factions and the remaining courtiers. Louis XIV’s character features in four of the total of seven dance scenes in the film, and in each case his appearance is clearly intended as a political metaphor. The first of these scenes takes place in the opening minutes of the film, with the Ballet de la Nuit, the first time that the fifteen-year-old Dauphin dances on stage, in the character of the god Apollo. This opening duly reveals several narrative and artistic elements: Lully’s devotion to the future monarch, to whom he offers a pair of shoes for scene; the choreography conceived as a cosmic metaphor in which the young prince, in the guise of Apollo, is already capable of subjugating some of the Grandees of the court who are seen dancing around him; the desire to impress his mother, Queen Anne of Austria, who, astonished by the magnificent figure of her son, exclaims “C’est un enfant!”, to which Cardinal Mazarin replies “Ce n’est plus un enfant. C’est un roi!”; attention to particular details of the practice of dance, such as Lully’s speech when he offers the shoes to the young Dauphin, noting that he had previously worn them to soften and ‘break them in’, making them suitable for dancing, or when there is a beautiful close-up of the legs and feet of the young Louis as he rehearses a few steps, and performs a simple warm-up movement, a plié and elevé—at this moment, the spectator well-versed in dance immediately realizes that this is the body of a professional dancer (in fact, a female dancer plays this brief role), and the expectation is created that this would be a film that will resort to professional dancers in the other dance scenes.

Figure 3 – Louis XIV as the Sun in Ballet royal de la nuit, 1653, drawing. Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), Paris.

Figure 4 – The Ballet royal de la nuit scene in Le Roi danse. (Corbiau 2000)

The film shows very clearly how the parallel between the royal figure and the god Apollo, or the elaboration of the cosmic image of the Sun King, materializes through dance. The only scene in which the dance master and choreographer Pierre Beauchamps appears is when the king is rehearsing in the company of courtiers (all played by dancers), who are moreover irrelevant to the story. The pretext for Beauchamps’s presence seems to be merely so that Louis XIV may abruptly end the rehearsal, irritated, and pronounce that the choreography requires more space, because the planets (the other courtiers) cannot overshadow the sun (the king). There is another interesting aspect in the setup of this scene, which runs parallel with the scene showing the worsening of the king’s mother’s illness and subsequent death. The choreography itself seems to grow in dramatic tension with the various cuts to indicate the mother’s physical agony. Continuing the symbolism, the last scene in which the king dances is again an Entrée d’Apollon, this time in the comédie-ballet Les Amants Magnifiques—which is, historically, the last time that Louis XIV danced on stage.8 This scene brings together two different moments, the rehearsal and the performance. Although once again embodying the image of the Sun King, it has another function in the film, that of showing resistance to the king’s claims to power over the court. The difficulty he has in performing the tour en l’air, filmed from different angles and shown repeatedly, and the fact that the king will fail on stage, are both meant to signify the fragility of the body politic. The scene ends with the comment of a watching courtier: “Bien qu’on dirait que l’État vacile. Personne n’est Dieu sur cette terre”.

There is no space here to analyse in detail the film’s seven dance scenes. But one may look at them from another perspective: the work of the choreographer. Béatrice Massin was a disciple of Francine Lancelot (1929-2003), choreographer and dance historian, who was one of those most responsible for the revival and study of the repertoire of French baroque dance. With the creation of her own fêtes galantes company in Paris in 1993, she continued her research into the historical sources on this repertoire, but she was fundamentally concerned with building a contemporary choreographic language, one that was her own, and which she termed “new baroque” or, more recently on the company’s new website, as “post-baroque”. The dance choreographies in Le Roi Danse bear the unmistakeable stamp of this creator.

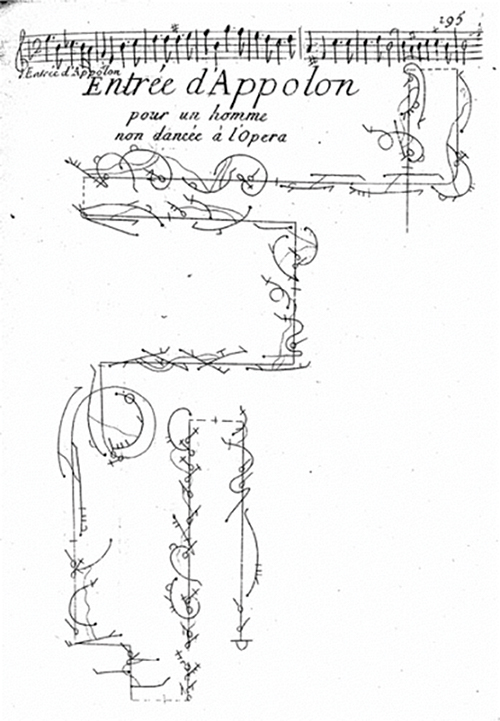

If, in the scene I have just described, one may discern steps from a historical choreography for a male solo from the “Entrée d’Apollon”—which in itself justifies the need to resort to a professional dancer as a double in some of the shots—in the other scene of the rehearsal with Beauchamps, also described above, Béatrice Massin creates an entirely new choreography from Lully’s musical score originally intended for a female solo:

La chorégraphie que j’ai réglé à cette occasion sur la musique de la “Passacaille d’Armide”, dansée par douze hommes, accumule une énergie que je pourrais définir comme masculine et donne à voir tout autre chose que la notation de la même danse attribuée à Mlle de Subligny. Même si cela se déroulait sur une forme circulaire, avec des qualités assez douces ordinairement connotées aujourd’hui comme féminines, puisque Gérard Corbiau voulait voir les planètes autour du soleil. C’était une chorégraphie cosmique. Lors de ce tournage, j’ai alors compris la puissance de cette danse dans des corps d’hommes. Il s’agissait de ma propre chorégraphie, mais j’ai beaucoup lu de danses d’hommes (Massin & Nordera 2015, 2).

The system of choreographic notation invented by Pierre Beauchamps and published in a manual by another dance master, Raoul-Auger Feuillet, all under the patronage of Louis XIV, contains directions for hundreds of solo dances, duets, and, at most, quartets.9

Figura 5 – Guillaume-Louis Pécour, “Entrée d’Apollon pour um homme non dansée à l’Opéra” (Feuillet 1704, 195).

But this system of writing did not record group choreographies, noting only some positions and figures, but not the movements or the steps. As a result, the other scenes, which are all group dances, are also designed by Béatrice Massin, some of them more faithful to the historical record than others (such as the brief choreographic moments in the staging of the tragédies lyriques at the end of the film, of scarcely any importance to the narrative, and not involving any of the protagonists), others boasting more contemporary movements (such as the danse macabre in the play Le Malade Imaginaire, which, ironically, is used for Molière’s death on stage), while yet others achieve a balance between the two registers, like the second dance scene in the film, a choreography for Idylle sur la Paix - Air pour Madame la Dauphine). All these parts are made to cohere and the artistic choices made are justified by the desire to give power and intensity to the scenes (another example of this are the vocal expressions, virtually shouted orders uttered by the dancer-king in the film’s second dance scene), creating dances distinguished by their extreme frontality, and all of them exclusively masculine:

Dans “Le Roi danse”, j’avais essayé de mettre des battus et des ronds de jambe parce qu’il me semblait important de faire découvrir aussi cet aspect de la danse baroque à un large public. Si je cherche à montrer la puissance d’un interprète sur scène, je ne la traduis pas par des séries d’entrechats, mais plutôt par une immobilité ou par quelque chose de très posé et de très affirmé. (Massin & Nordera 2015, 3)

The only thing missing, in my opinion, is attentiveness to another function of dance in the political games at the royal court. At the time, most of the group choreographies still involved the courtiers themselves, although there were already professional dancers. Being able to dance on stage with the Sun King was a privilege only granted to some as an instrument of social and political distinction. With the exception of the first scene of the Ballet de la Nuit, the only characters on the stage are the king, Lully, and Molière. In all other scenes, the remaining dancers are anonymous characters in the story, which means that this other political reading of court festivities is entirely lost.

What memory of the history of dance are we left with?

In conclusion, how might one answer the second question from the title? After analysing this varied set of scenes, what kind of memory is being created and transmitted by these period films?

First, it seems clear that there is a constant in all the artistic productions analysed here: directors and choreographers working together take advantage of the aesthetic and metaphorical power of dance scenes. In doing so, they make different decisions in a more or less informed way and in a manner that is more or less concerned with how these scenes may be read. In their responses to the challenges that arise when working with historical material there is surely an implicit dialectic rooted in their affective relationship with the knowledge of the past. This relation is subjective, proper to the identity of the artist, and rests much more on an idea of affinity than of authenticity.

There is also the matter of perspective. The observations made here will be relevant to those who study the history and practice of dance, but less so for other audiences. Most would find it strange if, in one of these films, a painter was seen to produce a royal portrait in the Impressionist style. However, few are able to find anything amiss when a dance is shown with steps and figures belonging to another style or era. In fact, the generalized lack of knowledge and habitual prejudices sometimes condition the construction of these scenes. On this point we might go all the way back to the origins and development of the art of dance and its historiography, constantly having to assert its equality with the other fine arts.

Le champ est si peu et mal connu, reconnu, qu’il est contraint d’exposer chaque fois son histoire et d’établir sa légitimité. [...] Alors que les différentes sciences des arts—musicologie, histoire de l’art (domaine où l’”art” devient synonyme d’”arts plastiques”), arts plastiques, études théâtrales ou cinématographiques—sont devenues autonomes et ont acquis une légitimité depuis longtemps, tel n’est pas le cas de la danse. [...] la science de la danse se trouve toujours tout en bas de la hiérarchie aussi bien des arts que des sciences. (Marquié 2014, 1)

In a 1981 New York Times article on the rediscovery of early dances, reference is made to the research and dissemination work of Ann Jacoby (choreographer of Valmont) and Catherine Turocy’s New York Baroque Dance Company, which recognized the difficulties posed by the lacunae in our knowledge of a practice that has not been conveyed to us directly (although it is the foundation of ballet) and which had to be deciphered from extant dance manuals: “People think it’s either cute or dusty”, notes Catherine Turocy. (Laine 1981)

Gérard Corbiau, director of Le Roi danse, did not initially want to work with a baroque dance choreographer, preferring someone coming exclusively from the sphere of contemporary dance.10 He feared that this historical genre of dance would transform its protagonist into an effeminate figure and that the story would lose all its credibility. It was very much to the contrary, however, as this period of dance history was dominated by men—it was only during the eighteenth century that the figure of the female dancer began to gain prominence—and dance, along with fencing and riding, was a key part of the physical education and social life of a nobleman. Béatrice Massin admits that there was a

[...] choc de la découverte du corps masculin lors des chorégraphies que j’ai crées pour le film “Le Roi danse” [...]. Voir la danse baroque avec une équipe d’hommes aussi importante a été pour moi [aussi] une révélation. (Massin & Nordera 2015, 2)

Understanding this baroque body, and the gestures and movement associated with it, not only through the costumes that clothe and condition it, but also through the physical actions and practices it was used to perform and enact, must also be part of the construction of the “world of the play”. A more profound study of this would require going beyond the dance scenes, and is not within the scope of this article. But it is a question that remains to be answered.

Of the five choreographers who worked on these films, as we have seen, only two were specialists in the period portrayed. Knowledge of the practice of this type of dance is still relatively recent, and it has only begun to acquire greater visibility in artistic and scholarly circles in recent decades—thus the process of claiming its space in public memory has been more protracted and complex. The opening observation made by Stephen Shapiro in his study of Roland Joffé’s film, comparing it with different adaptations of Vatel’s story, is relevant to the present question:

These abundant and diverse adaptations point to historical subject matter’s infinite recycling as subsequent generations refashion the past according to their own cultural circumstances and mentalities. This study takes as its point of departure Raymond Aron’s declaration that, “nous retenons du passé ce qui nous intéresse. La séléction historique est dirigée par les questions que le présent pose au passé” (Shapiro 2005, 78)

The collective memory that, in the words of Enzo Traverso, may be considered a more “human” history, because of this selective approach to the past, has presently invaded the public spaces of Western society. In his view, there is a ‘réification du passé’, that is to say, the transformation of the past into an object of consumption, which is currently being exploited by the tourism and entertainment industries, particularly television and cinema, due to their greater reach. At times, these uses of the past neutralize and simplify historical realities, for the sake of making a bigger impression, whether sociological or financial. However, increasingly the historian is being asked to participate in this process as a specialist (Traverso 2005, 10-11). This is evident in the composition of the artistic and technical teams of the films discussed here, as pointed out above, revealing an ongoing interaction between knowledge, and historical and contemporary performative arts. A study of this interaction, between historical knowledge and the artistic practice of the memory of the baroque, allows us to evaluate different planes of cultural preservation and renewal (as two distinct or complementary creative processes) in the transmission of dance heritage.

The memory of dance left by the selection I have analysed is generally consistent with both its universal function, and the role of dance at that particular time—as a social and theatrical art with implications for human as well as political relations. Much ends up being preserved in cinematic memory, even if it is always a construction, the artist’s subjective reading. Nevertheless, the image that remains of its technique, its style, the body which it moulds, the mentality that is projected on the stage, is not particularly consistent and is lost in the thick of other artistic intentions and designs. Meanwhile, with regard to the usefulness of these films for the history of dance itself, one is inclined to be even more demanding and critical. One thing that is certain however, is that in dance, performance is the device par excellence for communicating the history and memory of the past to the present—and cinema is one of the privileged means at its disposal.

Endnotes

1 The selection is not intended to be exhaustive and sought to bring together a set of films representative of the use of this type of dance in cinema. The selection criteria were as follows: films had to be originally made for the cinema; they had to include at least one dance scene; the dance had to fit generically into the category of baroque dance. There are other notable films that may have been analysed based on these criteria, but which could not be included due to lack of time and space, such as: Amadeus (1984), directed by Milos Forman, The Affair of the Necklace (2001) by Charles Shyer, Molière (2007) by Laurent Tirard, and El Baile de San Juan (2010) by Francisco Athié.

2 Not all of these eight films were French productions. However, from the list of six films that the author presents, three are analysed here: Marquise, Vatel and Le Roi danse.

3 These questions related to the history of dance of this period are developed further in my Master’s dissertation (Campos 2009).

4 My Master’s dissertation includes a study of dance treatises, in particular the three dance treatises printed in Portugal in the eighteenth century. (Campos 2009)

5 Due to plot demands, there are some historical inaccuracies in this film: the story takes place in 1683, the year of the inauguration of the Bosquet de Rocaille, which was planned by André Le Nôtre himself (and not by the fictional character Sabine de Barra), who would have been around 70 years old at the time (and not around 40, as he is portrayed in the film). The opening ceremony was a ball at which the Grand Dauphin, son of Louis XIV, danced. (Tunzelmann 2015)

6 For example, Jane Gibson choreographed the dances for various television and film productions of Jane Austen’s novels.

7 In Valmont we find a similar opera scene, albeit much less prominent, with brief glimpses of a choreographed dance for eight dancers on the stage (uncredited).

8 Coincidentally, the setting of this scene is the same Bosquet de Rocaille from A Little Chaos. Although Corbiau also takes some liberties with the choice of location, since the first performance of this ballet occurred thirteen years before the opening of the garden, the space is staged very differently from Alan Rickman’s film: the court is assembled in an orderly and hierarchical way and the orchestra is given a central place in the arrangement of the stage.

9 At the end of the seventeenth century, a system of dance notation was commissioned by Louis XIV, elaborated by Pierre Beauchamps, and set down in a book by Raoul-Auger Feuillet (Chorégraphie ou l’art de décrire la danse par caractères, figures et signes démonstratifs, Paris, 1701), dance masters at the French court, that still today gives insight into many of the choreographies of social and theatrical dances. The notation system, currently known as the Beauchamps-Feuillet system, records the steps of the various dancers, the figures they perform in space, and the relationship of these choreographic elements to music.

10 Milos Forman in Amadeus (1984) worked with the contemporary choreographer Twyla Tharp on the dance parts of the various opera scenes, whose style is integrated into the bold artistic vision of the production.

Bibliography

Alberts, David. 1997. The Expressive Body: Physical Characterization for the Actor. Portsmouth: Heinemann.

Belmont, Véra. 1997. Marquise. France: Pathé Films.

Campos, Alexandra Canaveira de. 2009. “Tratados de Dança Em Portugal No Século XVIII. O Lugar Da Dança Na Sociedade Da Época Moderna.” Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Universidade Nova de Lisboa. http://hdl.handle.net/10362/11979.

Castro, Maria João. 2016. “Dança e Cinema: O Pas-de-Deux Das Duas Artes Do Movimento Do Século XX.” AIM - Associação de Investigadores da Imagem em Movimento. http://hdl.handle.net/10362/21201.

Coppola, Sofia. 2006. Marie Antoinette. France; United States; Japan: Pathé Distribution; Columbia Pictures; Toho-Towa.

Corbiau, Gérard. 2000. Le Roi Danse. France; Germany; Belgium: Fox France.

Dargis, Manohla, and A. O. Scott. 2006. “‘Marie Antoinette’: Best or Worst of Times?” The New York Times, May 25, 2006. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/25/movies/25fest.html.

Douin, Jean-Luc. 2006. “‘Marie-Antoinette’: Une Reine Rock et Rococo.” Le Monde, 2006. http://www.lemonde.fr/cinema/article/2006/05/23/marie-antoinette-une-reine-rock-et-rococo_774975_3476.html.

Feuillet, Raoul-Auger. 1704. Recueil d’entrées de Ballet de Mr. Pécour. Paris: l’auteur.

Forman, Milos. 1989. Valmont. United States; France: Orion Pictures.

Hudelet, Ariane. 2006. “Chorégraphies Implicites et Explicites : La Danse Dans Pride and Prejudice, Du Texte à l’écran.” Études Anglaises 59 (4): 414–26. http://www.cairn.info/revue-etudes-anglaises-2006-4-page-414.htm.

Ivory, James. 1995. Jefferson in Paris. France; United States: Buena Vista Pictures.

Joffé, Roland. 2000. Vatel. France; United Kingdom: Gaumont.

Kubrick, Stanley. 1975. Barry Lydon. United Kingdom; United States: Warner Bros.

Laine, Barry. 1981. “‘Historical Dance’ Makes a Comeback.” The New York Times, no. March 8: 2002017. https://www.nytimes.com/1981/03/08/arts/historical-dance-makes-a-comeback.html.

Long, Robert Emmet. 2005. James Ivory in Conversation: How Merchant Ivory Makes Its Movies. Berkeley, Los Angeles, California: University of California Press.

Marquié, Hélène. 2014. “Regard Rétrospectif Sur Les Études En Danse En France.” Recherches En Danse 1: 1–7. https://doi.org/10.4000/danse.619.

Massin, Béatrice, and Marina Nordera. 2015. “La ‘Belle Dance’ Des Genres: Des Notations Anciennes à La Création Contemporaine.” Recherches En Danse 3: 1–17. https://doi.org/10.4000/danse.890.

Rameau, Pierre. 1748. Le Maître à Danser. Paris: Rollin fils.

Rickman, Alan. 2014. A Little Chaos. United Kingdom: Lionsgate.

Sellier, Geneviève. 2002. “Saint-Cyr, Le Film Historique Renouvelé Par Le Cinéma D’auteur-E.” Sites: The Journal of Twentieth-Century/Contemporary French Studies Revue d’études Français 6 (2): 395–401. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/718591976.

Shapiro, Stephen. 2005. “Roland Joffé’s Vatel: Refashioning the History of the Ancien Régime.” In EMF: Studies in Early Modern France. Vol. 10 - Modern Perspectives on the Early Modern: Temps Recherché, Temps Retrouvé, edited by Anne L. Birberick and Russell Ganim, 77–88. Charlottesville: Rookwood Press. https://books.google.pt/books?hl=en&lr=&id=QtjJxJoXx5MC&oi=fnd&pg=PA77&dq=%22le+roi+danse%22&ots=FBK-shtWmp&sig=XqrVjRbmAUSd-KXS42C72JWNOEA&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=%22le roi danse%22&f=true.

Traverso, Enzo. 2005. Le Passé, Modes d’emploi; Histoire, Mémoire, Politique. Paris: La Fabrique éditions.

Tunzelmann, Alex von. 2015. “A Little Chaos: Leads Historical Accuracy down the Garden Path.” The Guardian, April 23, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/film/filmblog/2015/apr/23/reel-history-a-little-chaos-alan-rickman-kate-winslet-palace-of-versailles.