Abstract

As this paper argues, chance is the key defining aspect of film, distinguishing it from other forms of art and communication. This is because film has the ability to capture a direct, mechanical imprint of the unpredictable movement of reality as a series of equidistant static images. Through the enhanced visibility (such as the close-up or slow-motion) and re-playability of this static state, film can reveal contingent nuances of this movement. Therefore, film can be seen as uniquely positioned on a semiotic threshold between movement and stillness – the infinitely complex movement of the real, and the conceptual stillness of language – translating randomness and chaos into aleatory significance, or revealing the unpredictable, contingent foundation of seemingly ordinary, habitual events.

On the basis of a creative synthesis of particular aspects of the philosophy and theory of Bergson, Deleuze, Barthes and others, this paper sets out chance as the defining semiotic aspect of film. Furthermore, the paper discusses and presents outcomes of a practice research in film, which used this theoretical synthesis as a rationale for practical exploration and experimentation – establishing chance as a significant expressive tool and aesthetic element of film practice. In this way, the paper presents new filmmaking methods uniquely rooted in film philosophy, while contributing to the expansion of the understanding of the nature of film and to the narrative/stylistic potential of cinema art.

Keywords: Chance, Semiotics, Experimental, Film Ontology, Bergson

Introduction

Chance (or contingency), as this paper argues, is a unique expressive aspect of film, which has a significant potential for film practice. My understanding of film is that it represents a threshold between the unpredictable becoming of reality and the conceptual stillness of human language and intellect. While film is (ontologically) a still structure made out of equidistant photographs, it captures a mechanical imprint of (something of) the movement of reality – namely, the movement/becoming of the particular arrangement of light in the moment of photographic capture. This captured moment usually has dominant coherent and meaningful aspects intended by the filmmaker: it is an image of something or someone, taken for some reason and in a certain context – such as in the context of a narrative film production. However, because of the indiscriminate automatism of the camera technology, an entire visual point in reality becomes captured within the de-limitation of the frame, which can contain various unintentional, aleatory elements, especially in situations where a great complexity of movement in reality is concerned. Due to the permanent nature of film, and its potential to generate enhanced visibility (such as through the close-up shot or slow motion), the aleatory aspects in reality can coincide within the still structure to generate a sense of semiotic significance. This sense of significance, as I argue, ultimately relies on the persisting tension between movement and stillness in film: film is a still, semiotic structure but it also gives us a privileged view of movement. This understanding of film was developed through a theoretical synthesis of particular writings of Barthes, Bergson, Deleuze and others, which I elaborate on in detail in the following section. However, this synthesis had also inspired and informed the formulation of a set of practical methods, which generated experimental filmmaking outcomes that to an extent illustrate the theory but also provide a certain non-rational insight into the particular understanding of film. Furthermore, the presented examples of practice operate as documentation of the kind of creative/artistic results that can be obtained through methodical (and methodological) pursuit of chance in filmmaking, as directly informed and influenced by the underlying theory.

As the related theorical and practical investigations equally suggest, a direct encounter with contingent reality is possible in film whenever unconstructed reality can enter the frame, no matter what kind of film it is. This aspect of the becoming of reality is nevertheless ordinarily assimilated into film’s coherent signification as narrative or a message that is being communicated. However, the element of chance can contribute to the destabilisation of the coherence of the image – it can contribute to a rupture of a coherent narrative signification and of a coherent representation of the filmed reality. If the aim of a film is to communicate a message or a story, then such intrusion of unintentional chance would usually end up on the cutting floor – as an undesirable mistake – and rarely it would find its way into the film. It is usually in art and experimental films where chance is recognised as a valuable contribution to the artistic impression of the film and deliberately included in its structure (there are many notable examples of this, such as in films of Stan Brakhage, Michelangelo Antonioni or William Greaves; however, elaborating on these examples in sufficient detail is beyond the scope of this paper). My practice nevertheless focused primarily on the ways in which chance can be captured and creatively utilised in film, using methods such as filming continuously (often with multiple cameras), so that unexpected moments of chance could unintentionally occur and could be subsequently discovered in the large quantity of footage obtained. Furthermore, the value of the practical outcomes lies in the fact that, as a practitioner, I can clearly account for the unintentional origin of the aleatory aspects of the image. This is critical, as, although I would posit that the expressive value of chance cannot be successfully staged or faked, we ultimately cannot be certain of the exact origin of images in film works where we don’t have access to a transparent account of the production process.

Nevertheless, as I allude to earlier, the philosophical/conceptual understanding of the unique expressive potential of chance in film preceded this practice and was in fact critical to both the framing and the interpretation of the practice. The understanding of film as a threshold between movement and stillness – being, in a fundamental sense, both moving and still at the same time – had a decisive impact on my practitioner positioning toward the process of filming and in that sense directly inspired and informed the creative process. It is therefore important to establish in detail the theoretical framework before presenting the outcomes of the practice.

Movement/Stillness: Bergson, Barthes and Deleuze

In Henri Bergson’s philosophy, the concepts of becoming and duration are fundamentally related, to the extent that they are in opposition (or in hierarchical supremacy) to abstract/geometrical space, and to individual objects moving through this geometrical space according to divisible, reversible time. These secondary, conceptual kinds of movement and time represent the way in which the human intellect understands and views the world. As Bergson (1944) points out, ‘we become unable to perceive the true evolution, the radical becoming. Of becoming we perceive only states, of duration only instants, and even when we speak of duration and of becoming, it is of another thing that we are thinking’ (297). However, for Bergson (2002) the true nature of reality ‘is global and undivided growth, progressive invention, duration: it resembles a gradually expanding rubber balloon assuming at each moment unexpected forms’ (226); reality, for Bergson, is the ‘flow of unforeseeable novelty … the moving originality of things’ (232). Or as Ronald Bogue (2003) puts it, ‘for Bergson the universe is a vibrational whole, various entities being diverse contractions and dilations of durée, and that vibrational whole may be thought of (with due caution) as time-space or matter-flow – that is, as universal movement, in which there is no division between motion and things moving’ (32). Bergson’s (2002) concept of duration reflects ‘the continuity of real time’ (211), as opposed to ‘spatialised time’, and is fundamentally related to consciousness; as he affirms, ‘we cannot speak of a reality that endures without inserting consciousness into it’ (207). However, the aspect of his philosophy more aligned with becoming – yet also fundamentally related to duration – which reflects ‘the perpetual flux of things’ (1944, 344), ‘the continuity of the real movement’ (377), is more useful to my ontological approach to film. As a practitioner, when I deal with the unpredictable unfolding of reality in the moment of filming, it is the aspect of movement that ushers in the radical novelty and chance in reality. Furthermore, making aesthetic decisions about the creative process, including the experience of working with the film material in post-production, makes the ontological stillness of film a methodological given. Therefore, negotiating movement and stillness (and creatively utilising the potential that arises at their intersection) is a critical aspect of the practice. Significantly, however, it is the understanding of movement and stillness rooted in Bergson’s philosophy that is at stake: real movement (becoming) and human, conceptual stillness (meaning) – and film as a threshold between the two.

As I allude to in the introduction, in order for the becoming of the real (as Bergson understands it) to register on film as something noticeable, this trace of the becoming of the real has to stand in marked distinction to the film’s intentional and controlled communication. This is precisely what I mean by chance, by contingency: something specific and noticeable that happens – and is registered on film – without anyone intending or planning for it to happen. In her discussion of early cinema (and especially the documentary-style ‘actualities’ from the early 20th century), Mary Ann Doane (2002) points out film’s unique ability to capture contingency – to capture the ‘immediacy of the real’, the ‘pure present’ (151). She claims that ‘the specificity of photography as a representational form has been, and continues to be, situated as a privileged link to the contingent’ (142). In other words, she identifies film’s specificity – its undiscriminating viewpoint – as the key aspect of its ability to capture contingency. For contingency ultimately testifies to the unpredictable complexity of the becoming of the real, transcending human intention and control. However, the aleatory origin of a moving image in the unpredictable becoming of reality can either be accounted for or it can merely be assumed. While reading for contingency in cinema has to usually rely on the latter, the production of new film work allows for an enhanced insight into the emergence of the image, and hence into the degree of intentionality and control that was involved. What is more, certain experimental methods can be implemented, which aim to maximise the element of chance in the film material (I outline these in the following section).

Chance in cinema ultimately exist within, and emerges from, the ontological stillness of film as a series of static frames. And, indeed, both still photography and film have the propensity to capture chance, and there is, therefore, an important, ontological identity between still photography and film. After all, even a still photograph requires a certain time to be exposed, so perhaps the difference is in the extent of duration of real movement preserved, rather than an ontological difference between movement and stillness as such. Certainly, the duration of film gives a radically enhanced impression of real movement, but perhaps that is not so much a qualitative such as a quantitative difference (at least from the ontological perspective). What is much more important, I would argue, is that in either case real movement is preserved and contained as still. Still, not in the superficial sense that it doesn’t appear to be moving – as is self-explanatory in the case of a photograph – but rather still in line with Bergson’s (2002) philosophy: ‘unwinding a roll ready prepared’ (177), always there in an identical sequential order, always ready to be re-played, always ready to be read. In this regard, both film and photography are inherently semiotic – always opened up to semiosis as a text – however, not in the sense that they necessarily have to represent something already specific and intelligible, but rather that new representational links can be invented, discovered, agreed upon, and even, intuited or felt. Film is always there, as a static, objectively verifiable audio/visual sequence and structure, and yet, as Mullarkey (2009) points out, in relation to Bergson, ‘the new can only be felt’ (211, emphasis in the original). Therefore, the unexpected or unintentional expression of chance as always new and singular – never following a predefined pattern or a code driven by habit, intention or intelligible communication of meaning – can perhaps only be read in the stillness of the images on the level of feeling and intuition. This level nevertheless ‘overcomes the duality of rationalism and emotivism’ (211) as affect (I explain what I mean by affect later on in this section).

In ‘The Third Meaning’ (1977a, 52–68), Roland Barthes outlines precisely this kind of loose semiotic connection, which fundamentally depends on the contingent alignment of the real within a photographically captured frame. He studies closely particular still images taken from a feature film, which leads him to distinguish three layers of meaning: the first is an informational level (this is the level of communication, the story, the message of the film); the second is a level of symbolism (this is a semiotic level beyond message, but nevertheless lucid and intentional; it is composed of various symbolic elements readable for a clearly identifiable and justifiable signified, whilst applying the fields of knowledge such as psychoanalysis, economy and dramaturgy); the third level then contains the third meaning.

The third meaning appears to Barthes as a surplus of meaning, a certain insistence of the image after all intelligible meaning has been extracted from it: he can describe in detail the various aspects of the signifier, without being able to (linguistically) grasp the signified – it bears a significance, without signifying anything. It is ‘at once persistent and fleeting, smooth and elusive … appears to extend outside culture, knowledge and information … opening out into the infinity of language … indifferent to moral or aesthetic categories’ (54–55). The third meaning is unintentional, hidden away under the layer of obvious symbolism and ‘carries a certain emotion’ (59, emphasis in the original). The third meaning subverts and surpasses the story of the film – through its insistence and significance – and therefore represents the filmic: the visual, which is unique and peculiar to film, outside of narrative and traditional meaning; a ‘representation which cannot be represented’ (64).

It is quite paradoxical that the true essence of film should be expressed exclusively through a still image, and Barthes is aware of this paradox. He nevertheless cannot help but seeing the ‘filmic time’ as a constraining obstacle, preventing the third meaning from asserting itself in motion. Furthermore, he insists that the still ‘is not a specimen chemically extracted from the substance of the film, but rather the trace of a superior distribution of traits of which the film as experienced in its animated flow would give no more than one text among others’ (67, emphasis in the original). However, Barthes’ description of the third meaning is perfectly consistent with the expression of chance in film, and in fact, I would argue it is precisely the traces of real movement which are reflected in the still image for Barthes: on the threshold between real movement and film’s ontological stillness.

What is more, the illusion of movement in film imbues film with a sense of living duration, as its time has to coincide with the becoming of reality each time it is being re-played. That gives film a sense of its own becoming, independent of the activity of the mind of the viewer. The significance that Barthes recognises in the photograph only endures in the mind; whereas film endures in its own right, producing its own sense of internal vision, stirring the traces of real movement in new contexts, becoming with reality anew. This corresponds with Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s (1994) understanding of affects in works of art as independent of both the viewer and the creator, as the ‘nonhuman becomings of man’ (169, emphasis in the original): they exist independently of the human being as a subject – they exist as ‘sensible experiences in their singularity, liberated from organising systems of representation’ (Colebrook 2001, 22). Furthermore, the power of cinema, for Deleuze, lies precisely in its ability to create new realities, new affects, rather than representing specific things as perceived in reality.1

The concept of affect in film represents, I argue, precisely the point of contact between the real and the image, the point at which the real becomes imprinted on the image as a kind of trace: an echo of real movement. At the same time, the tension between these echoes of real movement and film’s ontological stillness persists in film. One way of understanding this tension between movement and stillness is to think of it as overtonal resonance 2 – a secondary, collateral vibration of the various elements of the moving-still structure of the film. Overtonal resonance can be understood as a complex, unpredictable resonance that transcends the distinction between dissonance and consonance. As the still structure of film becomes animated through movement, the echoes of real movement start to resonate within this structure; they come alive, so to speak. Overtonal resonance, in this sense, is precisely the aspect of becoming in the film – as it is being played – that differentiates it from its ontological state as a series of static frames, without ever entirely negating this static nature. On the contrary, it is precisely the static nature of film that can give rise to overtonal resonance once it is brought to life through playback or projection (although it can likewise give rise to jarring, avant-garde dissonance, or consonant narrative engagement and satisfaction).

The stillness of film can imbue the captured chance with significance, as Barthes describes it; but this significance is continuously animated within the moving-still structures of film, which makes it take on a more autonomous function within the film as affect. The expression of chance in film is therefore not the meaning of inter-subjective human communication, but a nonhuman exchange between the real and the moving-still, virtual-yet-permanent field of the moving image. In other words, in the shadow of human intention and communication, chance can imbue film with a sense of nonhuman intention and significance, which can be read or understood as affect.

The Implementation of Chance in Experimental Film Practice

As I explain earlier, the synthesis of film theory and philosophy elaborated on in the previous section formed a specific basis for film practice experimentation. The aim of the practice was to produce instances in film where the element of unpredictable reality creates an expressive sense of significance, similar to how Barthes defines his third meaning but also fundamentally linked to movement and affect. Or rather, the expressive potential of chance is linked to a marked tension between movement and stillness in film, which I refer to as overtonal resonance. The methods employed in the process of production were primarily oriented toward creating conditions in which the opportunities for ‘significant chance’ to registerer on film could be maximised. The underlying practitioner approach was to generate an excessive amount of footage and to record continuously without making regular decisions about when to start or stop recording – decisions about what is and is not valuable to capture. This method was one of the ways in which conscious intention could be suspended, but it was also building on the fundamental duality between movement and stillness explained in the previous section. In the moment of filming, I was aware of the function of the camera as a kind of portal between the unpredictable becoming of reality and the permanent stillness of all the recorded images. Rather than making decisions about what to film, how to film it and what the purpose of this process is, the approach was to absorb indiscriminately the surrounding flow of reality, while also being an inherent part of this flow. Therefore, instead of planning ahead of time, I focused on filming in environments with a strong sense of flux, where a lot happens and changes, while increasing this sense of flux in the images by being constantly on the move with the camera. Ultimately, in order for chance to create a sense of significance in film – as overtonal resonance – there has to be an element of visual movement involved, which gives rise to a tension between the echoes of real movement and the still, semiotic permanence of the series of static frames. Therefore, the decision was to maximise the opportunities for unpredictable movement of both the camera and the surrounding environment.

The filming process consisted of passing through busy urban environments – without intending to get to or arrive at anywhere particular – while constantly filming and while following one or two performers, so that the focus of the camera was not oriented toward anyone not wishing to participate in the film. Furthermore, the human body itself can create a marked sense of echoes of real movement and be a source of contingency (as some of the examples below illustrate). Elena Del Río (2008) identifies film as a ‘privileged medium for the exhibition of bodies’ (10). In film, Del Río explains, ‘whatever happens to a body becomes instantly available to perception. Thus, the performing body presents itself as a shock wave of affect, the expression-event that makes affect a visible and palpable materiality’ (10). She sees performance to be the source of the real (movement) in film, the aspect that disrupts film’s narrative or formal structuring tendencies: ‘as an event, performance is cut off from any preconceived, anterior scenario or reality. In its fundamental ontological sense, performance gives rise to the real’ (4). Dieter Mersch (2012) then claims that the presence of the body within the still structures of film leads to an ‘enhanced visibility, concurrent with a never-before-seen manifestation of the human body’ (448). This enhanced visibility can be achieved in film by both the close-up shot and slow motion, and I employed both techniques in the practice, in order to maximise the potential of chance to generate significant expression as overtonal resonance. For Walter Benjamin (2008), the close-up ‘brings to light entirely new structures of matter’ while ‘slow motion not only reveals familiar aspects of movements, but discloses quite unknown aspects within them’ (37). Through the revelatory power of the close-up and slow motion, as Benjamin suggests, film gives rise to the ‘optical unconscious’ – a term which is compatible with Deleuze’s ‘nonhuman affects’ produced outside of human control or intention. Furthermore, the close-up is also critical to Jean Epstein’s (1977) ‘photogénie’, which opens up ‘the cinematic feeling’ (16) in the film. Photogénie is therefore compatible with my understanding of nonhuman affects resulting from the expression of chance through the overtonal resonance between movement and stillness.

As some the following examples illustrate, the close-up and slow-motion techniques contributed to the production of what I argue is a sense of overtonal resonance – resulting from an element of chance being trapped in the still structures of film. While I cannot factually evidence the semiotic effect of chance giving rise to nonhuman affects – and in that sense my description is merely an interpretation, similar to Barthes’ account of the third meaning in a still image – I am nevertheless able to comment, as a practitioner, on the origin of the images in terms of what was intentional and what was not. I present the visual examples as a left-to-right sequence of a few frames removed from each shot in question. While this does not give the reader full access to the overtonal resonance initiated by movement, it nevertheless brings attention to the still, semiotic permanence of film. This presentation therefore puts an emphasis on the fact that it is ultimately a sequential structure of still photographs that carries the affective expression, rather than a single, isolated frame removed from the film, as is the case with Barthes’ interpretation of the third meaning.

Examples of the Practical Outcomes

While continuously filming on locations around London, I obtained a long Steadicam shot following a performer along a busy London Underground platform. (Image 1) The human figures passing along and against the flow of the camera are out of focus, due to the narrow depth of field of the camera focused on the back of the performer. This visual softness helps to emancipate the image from an ordinary sense of reality but does not take away from the serendipitous alignment of movement in the situation: as the camera makes a sweeping motion to the left, a woman runs by, her reflection caught in the glass wall separating the platform from the tracks. As she passes the frame, the train doors close, and the train begins to depart, coinciding with the fast-paced progression of the camera forward and the continuous flow of people in both directions. This wholly un-staged moment in time occurred just once, in absolute singularity – the contingent echo of real movement captured and stilled, creating a moving-still expressive structure.

Image 1

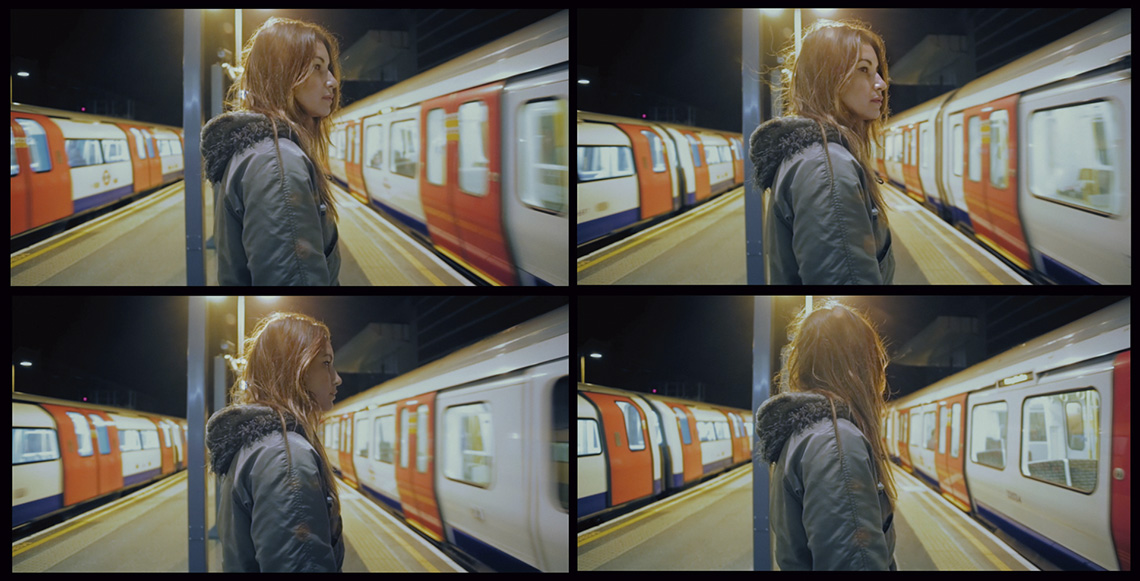

In a different example (Image 2), a performer stands on an outdoor platform, when two London Underground trains arrive at the same time on both sides of her. This was not planned or staged, but just happened in the moment of filming; we were merely waiting to board the train, and the centre-framing of the performer was intuitive, based on the immediate circumstances. The fact of the two trains simultaneously arriving, as well as the back illumination of the performer created by the lamp right above her, was only ‘discovered’ in the editing room. As the trains burst into the platform they send ripples of air, and the backlight illuminates individual hair oscillating in the rapid vortex forming around the performer’s head. The wind coincides with a slight swaying of the camera, perhaps contributing to it. The advance of the two trains, the wind, the pulsating camera, and the stirring eyes of the performer intently following the passing carriages in front of her all coincide to create a sense of unified movement, as if the whole image was pulsating with a single in-and-out breathing motion, synchronised to the living, heart-beating presence of the performer to the camera and to her immediate environment – the pressurised becoming of the real. Suddenly, an electric discharge on the roof of the left-side train briefly sparks into the night, to further illuminate the singularity of this contingent moment in time, now solidified (and discovered/delimited) in the digital film as an echo of real movement, expressing nonhuman affects as significance.

Image 2

In another moment, a performer stood in front of a doorway between the underground train carriages; the intense air blowing through the small window in the door makes her hair swirl around. (Image 3) This complex movement is complicated further by the camera with fixed focus and shallow depth of field making slight, gliding adjustments back and forth, creating a sense of fluid oscillation between image softness and points of focus – especially the alternating focus on the performer’s hair and her face. Here, therefore, the close-up framing is employed to bring attention to the unpredictable complexity of the movement of the hair, which is initiated by the aleatory passage of air through the train carriage. The camera movement contributes to this complex structure of movement, in order to create a singular arrangement of unpredictable complexity that carries nonhuman affects, and the origin of which is primarily defined by chance.

Image 3

An additional method of maximising the opportunities for chance to register on film was the use of a custom-designed shoulder rig with two cameras mounted side-by-side. This meant that I could only operate one of the cameras at a time, so that the second camera filmed ‘unconsciously’ (without my continuous control over what and how it was filming), with its particular movement and framing resulting from my attendance to the other camera. However, one specific shot emerged when following a performer toward a filming location, while not temporarily attending to either of the cameras. Both cameras were nevertheless recording, and one of them accidentally captured a shot that, due to the use of slow motion, forged a captivating visual structure, possessing an expression relatable to both Deleuze’s nonhuman affects and Barthes’ significance of the third meaning. (Image 4) The slow motion smoothened the wild jumps caused by my steps – here emphasised by using a macro lens at an extended focal length, which, on the other hand, resulted in reduced depth of field of the image (increased softness). The low depth of field, combined with the random, slowed-down motion of the camera, and the singular movements of the performer (revealed and amplified through the slow motion), here produced a strong sense of aleatory significance in the moving-still structure of the shot.

Image 4

Conclusion

The synthesis of the conceptual fields surrounding Bergson, Deleuze and Barthes represents an original scholarship in film theory, which is concerned with a particular audio-visual, semiotic effect of film produced by an overtonal resonance between contingent movement and film’s ontological stillness. Overtonal resonance, a term borrowed from Sergei Eisenstein, is essentially a complex, unpredictable resonance that transcends the distinction between dissonance (formal, avant-garde play) and consonance (seamless impression of reality and/or narrative engagement). The specific notion of movement (as opposed to film’s ontological stillness) is derived from Bergson’s philosophy and relates to the incessant emergence and becoming of reality (the real movement), which the human intellect can only perceive conceptually as stillness. The tension between this kind of movement and how it registers on film (due to its nonhuman, mechanical vision) can be understood as an echo of real movement, which represents the point where the contingent movement of the real becomes imprinted within the still structure of film – having the potential for rupture to the coherent, meaningful, communicative strand of the film, similar to Barthes’ third meaning. This encounter of real movement and stillness – when animated through film’s illusory movement – can generate nonhuman affects (indeterminate, impersonal, singular feelings self-contained in the image), which can ultimately be considered a direct audio-visual expression of contingency unique to film.

This theoretical synthesis and the generation of new concepts inspired and informed practice that aims to illuminate the expressive potential of film by utilising the inherent tension between movement and stillness, while using chance as a creative and structuring principle. Furthermore, the practice both illustrates and consolidates these concepts – entering into a creative dialogue with the underlying theory. The practical methods also represent new knowledge relevant to film practice and practice-as-research in film. My approach was informed by established methods of film production (primarily shaped by my practitioner knowledge, experience and education), but also by the specific aims of the project rooted in the fundamental, ontological aspects of film – especially film’s distinctive potential to capture and reveal contingency. These practitioner aims and considerations therefore have validity and applicability in the context of broader filmmaking, since all film production carries the opportunity to utilise the tools unique to the medium: not only to produce and communicate meaning, but to transcend meaning and communication – in a way only film is able to do.

Final notes

1Steven Shaviro (2010) and Brian Massumi (2002), in their writings inspired by Deleuze, distinguish between affect and emotion, which is a helpful distinction when defining affect. Emotion is a specific and qualified experience of a subject, confining or reducing affect to an intelligible (human) form, which nevertheless always has a certain affective surplus beyond meaning and outside the boundaries of subjectivity (Shaviro 2010, 4).

2I borrow the term ‘overtone’ from Sergei Eisenstein’s concept of ‘overtonal montage’, developed in his essay ‘Filmic Fourth Dimension’ (1949), who in turn borrows the term ‘overtone’ from acoustics, and specifically from experimental orchestral music, where overtones – secondary, collateral vibrations of a dominant tone – are the ‘most significant means for affect’ (66). These visual overtones are experienced by the viewer, according to Eisenstein, on a ‘physiological level’, in the sense that perception is a ‘higher nervous activity’ than merely ‘psychic’ processes: ‘in this way, behind the general indication of the shot, the physiological summary of its vibrations as a whole, as a complex unity of the manifestations of all its stimuli, is present. This is the peculiar “feeling” of the shot, produced by the shot as a whole’ (67, emphases in the original). More importantly, Eisenstein asserts that the visual (or musical) overtone cannot be perceived outside movement: it only emerges ‘in the dynamics of the musical or cinematographic process’ (69, emphasis in the original). Therefore, visual and aural overtones are of the same kind, of the same substance, belonging to the ‘fourth dimension’ of time (movement), which is the dimension of physiological sensation: the overtone is not heard or seen, but felt (70–1).

Bibliography

Barthes, Roland. 1977. Image Music Text. Fontana Press.

Benjamin, Walter. 2008. The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility and Other Writings on Media. Harvard University Press.

Bergson, Henri. 1944. Creative Evolution. New York: The Modern Library.

Bergson, Henri. 2002. Key Writings. Edited by K.A. Pearson and J. Mullarkey). London. New York: Continuum.

Bogue, Ronald. 2003. Deleuze on Cinema. New York, London: Routledge.

Colebrook, Claire. 2001. Gilles Deleuze. London, New York: Routledge.

Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix. 1994. What is Philosophy?. New York: Columbia University Press.

Del Río, Elena. 2008. Deleuze and the Cinemas of Performance: Powers of Affection. Edinburgh University Press.

Doane, Mary Ann. 2002. The Emergence of Cinematic Time: Modernity, Contingency, The Archive. Harvard University Press.

Epstein, Jean. 1977. “Magnification and Other Writings” in October, vol.3: 9-25.

Eisenstein, Sergei. 1949. Film Form: Essays in Film Theory. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Massumi, Brian. 2002. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Mersch, Dieter. 2012. “Passion and Exposure: New Paradoxes of the Actor” In Acting and Performance in Moving Image Culture: Bodies, Screens, Renderings, edited by Jörg Sternagel, Deborah Levitt, and Dieter Mersch, 447–77. Transcript Verlag.

Mullarkey, John. 2009. Refractions of Reality: Philosophy and the Moving Image. Palgrave Macmillan.

Shaviro, Steven. 2010. “Post-Cinematic Affect: On Grace Jones, Boarding Gate and Southland Tales” in Film-Philosophy 14.1: 1-102.