Abstract

The art of location-based Sound Recording specifically, has been a neglected area of academic research. I seek to address this by drawing critical attention to the intricacies and skills involved in location Sound Recording within single-camera Observational Documentaries (ObsDocs). I show how this art continues to be central to the creative process of production, in driving the narrative and shaping the text’s influence, within the pro-filmic space.

I go on to consider the future for location-based Sound Recording within ObsDocs and its place in a new multi-platform, multi-screen consumption space. Examining a case study, I seek to develop and define a new working methodology and aesthetic for the craft and art, predicated on an anticipated resurgence of the ObsDoc genre, centred around opportunities afforded by the emerging technologies of immersive sound: ambisonic microphone arrays being a vital part of that development. Ambisonics is a method for capturing a full 3D sound field, and its genre-bridging adaptability means it can be converted to a dynamically steerable binaural format. I argue that deploying an ambisonic-centred location Sound Recording methodology, fused with the art of recording unscripted actuality Sound within the pro-filmic geographic event-space, will offer new creative opportunities impacts for ObsDoc makers and crucially, tomorrow’s Documentary audiences. Presenting audiences with an exciting new ability to experience the sense of geographical place and physical event that immersive audio delivers, bears the potential of re-invigorating a content driven ObsDoc market, which once again, will foreground the primacy of neglected storytelling capabilities, in a New consumption World.

Keywords: Ambisonics, Observational, Documentary, Sound, Recording.

Introduction

As an Observational Documentary Sound Recordist of 25 years, I hypothesise that the role has an authorial voice and a creative agency.

My academic interest is to reflect on practice and so to reimagine and develop through practice-based research, an ontological re-defining of location Sound Recording, aimed at reinvigorating the ObsDoc genre by connecting single camera story-telling skills with new technologies, within a new multi-platform, multi-screen consumption space.

It is often the Director that is credited as the sole author of a film and if critical discussion recognises the role of crew at all, it is usually around Cinematography: rarely Sound. Indeed, outside of the realms of music and post-production, the role of Location/ Field Sound Recording is a neglected area of film criticism and academic literature.

The place of Location/ Field Sound Recording authorship is equally open to question. Paul Sellors observes that ‘Auteurists have tried to explain a film’s coherency by overvaluing the authorial control and artistic aptitude of an individual’ (Sellors, 2007, 268). Gaut as quoted by Sellors argues that the authorial should in fact be “multiply classified: by actors, cameramen, editors, composers, and so on.” (ibid, 267). As Sellors summarises this perspective: “Gaut, instead, looks at the function of a collective to get from individual contributions to a completed text.” (ibid, 268).

To illustrate this authorial ambiguity, Sellors further comments:

Is the sound recordist a member of a film’s collective authorship? This is not so simple to determine. Some sound recordists will count as authors under a notion of collective filmic authorship while others will not. It will depend on the recordist’s contribution to the filmic utterance... we need to understand this person’s role in producing not just the material film, but also its utterance.” (ibid 269).

This paper seeks to address these questions posed around ‘contribution’ and ‘utterance’, specifically of the work of the Location/ Field Sound Recordist within the Observational Documentary sphere.

One, possibly singular, but notable exception to the dearth of academic study in the arena of Location/ Field Sound Recording is Chesler in Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media - “Truth in the mix: Frederick Wiseman’s construction of the observational microphone” (2012). This analyses the role of Sound Recording in Fred Wiseman’s observational documentaries and identifies his approach in the ‘construction of the observational microphone’. Wiseman is one of America’s most prominent directors of documentary who, along with contemporaries, the Maysles brothers, Don Pennebaker and Richard Leacock, helped establish the American Direct Cinema tradition of the 1960s. As Barnouw in Robinson recognises:

This tradition emerged in the wake of specific technological developments – most obviously the disaggregation of camera, microphones and tape recorder, enabling synchronised sound shoots for the first time. (Robinson, 1993, 11).

It sometimes goes unnoticed that as well as Editing and de facto Directing, Fred Wiseman was and also still is, the Sound Recordist on his films.

Part 1 - Setting the Scene: What Typifies an Obsdoc

Wiseman in an interview with David Winn for The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences, observed that:

Observational cinema somehow seems to suggest that you just turn the camera on and let things happen in front of you, when in fact all aspects of movies are the result of thousands of choices. (emmyonline.org, 2014).

It is these choices that arguably define the Observational Documentary genre but Wiseman’s comments also highlight the tension imposed by the ambition of ObsDoc filmmakers to minimise the mediation of reality and so to aspire to present to the viewers a sense of ‘being there’ (a defining term used by Richard Leacock), with Wiseman’s own comment that “The notion that cinema is the truth, or that anything is the truth is preposterous… Everything is subjective, and everything represents a choice.” (ibid. 2014).

Those thousands of unscripted choices within the ObsDoc production process, pose questions around the authorial voice too, not only because of the inherent tension Wiseman identifies between a film grammar that seemingly presents to the viewer ‘reality’ unfolding ‘as it is’ and the constructive nature of filmmaking, but also around the particular production context of the genre.

Observational Documentary does not just exist in spectatorship; crucially, it also exists in the actual – in the physical event-space. This involves literally sharing ‘slices of life’ with protagonists and being part of unscripted events, thus requiring a ‘reactive’ approach relying in many ways on the relationships forged within the making process: inter-protagonist; inter-spatial and inter-makers. Filming in that ObsDoc profilmic space (as defined by the world the camera lens sees) centres around a pre-emptive, situation-specific, choreography of Camera/ Recordist, around ‘action’. I exemplify what I mean in this 2’48” clip (Cutting Edge: Bad Behaviour-Ben 2003). Link to the film clip is HERE (YouTube): https://youtu.be/VBDVmA7E4dM

To set the scene, the location is a small front room in a house in Southampton, UK; time of day is evening. The protagonists are Ben Webb (son); Tilly Webb (sister); Sally Webb (Mother), and Colin Webb (Father). The filming crew are Hilary Clarke (Director); Steve Whitford (Sound) and author, and Jeremy Humphries (Camera). The film centres around the work of specialist teacher, Warwick Dyer who:

…believes that chronic bad behaviour creates what he has termed an “interactive behaviour imbalance” (www.ibi.org.uk). He does not see “bad behaviour” as the child’s problem at all but an interactional problem between child and authority figure which the child is incapable of changing. Warwick therefore works exclusively with the parents and teachers, through their accounts of what is happening, and does not see or interact with the children themselves. (Dyer, 1997).

| TIME | VISUALS | SPEAKER | DIALOG |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Ben at computer - mid shot (m/s) | Sally Web 0:00 | First thing we’re going to try and do to make it a lot lot better indoors is not swearing. |

| 0.05 | Close up (c/u) pillow. Tilly talking. | Tilly Web 0:06 | You said that years ago… |

| 0.08 | Wide shot (w/s) Sally & Tilly on sofa. Dogs playing. | Tilly Web (cont’d) | ...you were going to stop smoking... stop swearing. Where’s it gone? You’re still doing it. So, what’s the point in having rules? |

| 0.14 | c/u dogs playing. | Sally Web 0:14 | Well, everything has got too bad in here, hasn’t it? |

| 0.18 | w/s Sally & Tilly on sofa. Dogs playing. | Sally Web (cont’d) | Too messy in here, wish these dogs would stop… |

| 0.2 | m/s Sally picking-up a dog. | Sally Web (cont’d) | Right so the rules is I mustn’t swear… |

| 0.23 | c/u Tilly’s feet on sofa. | Sally Web (cont’d) | ...you mustn’t swear, and we really, really got to try. |

| 0.27 | m/s Sally on sofa with 2 x dogs. | Sally Web (cont’d) | If you’re gonna swear, and keep on swearing at me and Daddy, then obviously... you know, we’re gonna have to think of something to stop, you know? Stop you from swearing is say something like, take a bit of your pocket money away. |

| 0.42 | c/u Ben at computer. | Sally Web (cont’d) | Are you listening Ben? |

| (cont’d) | Ben Webb 0:43 | Yeah, fuck off. I will always swear. And there’s nothing you can do about that. I’m not... | |

| 0.48 | c/u Sally on sofa with teacup. | Sally Web 0:48 | But it’s not pleasant is it anyway? |

| (cont’d) | Ben Webb 0:49 | I don’t care, I’m still swearing - I like swearing. | |

| (cont’d) | Sally Web 0:50 | But it’s not a way to communicate with people, is it? | |

| (cont’d) | Ben Webb 0.52 | I don’t give a fuck, you old bag. | |

| 0.55 | c/u Ben at computer. | Ben Webb (cont’d) | The only way to get your own way is by swearing. |

| (cont’d) | Sally Web 0:57 | Yeah, but we’re not... we’re not… | |

| (cont’d) | Ben Web 0:58 | I don’t give a fuck. Cunt... yeah, your mother suck cunt. | |

| (cont’d) | Sally Web 1.00 | Yeah but you swear when you’re not angry. | |

| 1.02 | c/u Sally on sofa. | Now in order to help us stop swearing... | |

| 1.06 | c/u Ben at computer. | Ben Webb 1:06 | Suck your mum’s cunt. |

| (cont’d) | Sally Web 1:07 | ...then we’re gonna have to work a way that, I dunno, made you lose some of your pocket money. | |

| (cont’d) | Ben Webb 1:12 | Yeah? Fucking do that and I’ll punch you in the face, you fat cunt. | |

| 1.16 | c/u Sally on sofa with teacup. | Ben Webb 1:16 | Don’t start me off now or I’ll punch you straight in the face now. |

| (cont’d) | Narrator 1:1 | Ben finds even the mention of a fine a threat to his power. | |

| (cont’d) | Sally Web 1:19 | That’s the only way I can think about getting some order in the house. | |

| (cont’d) | Ben Webb 1:22 | You do it go do it that I’ll start I’ll smash the window now. [SMASH] Want me do it again? I’ll get all the cups and smash ‘em. | |

| 1.32 | c/u Ben at computer, turns. | Ben Webb (cont’d) | Next time it’ll be the window. |

| 1.34 | m/s over-shoulder (ots) Ben, Sally sweeping-up. | Ben Webb (cont’d) | You take any of my pocket money or anything away from me, you’ll fucking know it because all the windows will be through. |

| 1.38 | c/u glass fragments being swept into dustpan. | Sally Web 1:38 | No, Benjamin, if you damage things, you’ll have to pay for it. |

| 1.41 | m/s Ben ots, Sally on ground, sweeping. | Ben Webb 1:41 | How am I gonna pay for it - I don’t have my own fucking money anyway. |

| (cont’d) | Sally Web 1:43 | No, I’m not saying... | |

| (cont’d) | Ben Webb 1:44 | [Shouts] How the fuck am I gonna pay for it, you thick cunt? | |

| (cont’d) | Sally Web 1:46 | I’m not saying... | |

| 1.48 | (cont’d) Ben picks up teacup. | Ben Webb 1:48 | Oh, fuck off. I will… |

| (cont’d) | Sally Web 1:49 | ...I’m going to stop all your pocket money, at all. | |

| (cont’d) | Tilly Web 1:50 | [Shouts] Stop it. | |

| 1.51 | c/u, over the shoulder, Ben at pc screen. | Sally Web 1:51 | Patch you’re gonna get hurt in a minute. Come on, you’re gonna get hurt. |

| Ben Webb 1:53 | Patch - come here. | ||

| 1.56 | m/s Ben picking-up Patch (dog). | Sally Web 1:56 | Check her feet that she aint cut her... |

| (cont’d) | Ben Webb 1:57 | [To dog] Stop. Stop. | |

| (cont’d) | Sally Web 1:58 | Just make sure they’re not bleeding. [Sweeping glass] | |

| 2.03 | m/s continues checking dog with Tilly. | Sally Web 2.05 | No. No - I can’t see it all. Oh, it’s everywhere. |

| 2.09 | m/s Camera drifts up to Sally at lounge door. | Ben Webb 2:09 | If she stops any of my money, I’ll swear I’ll... |

| (cont’d) | Tilly Web 2:11 | She won’t - she’s only saying it… | |

| 2.13 | c/u, ots, Ben at pc screen. | Tilly Web (cont’d) | ...they’re soft, Ben. They won’t do it. |

| 2.15 | w/s. Ben at pc; Sally enters. | Sally Web 2:16 | Well, I’m being serious. |

| (cont’d) | Ben Webb 2:19 | Are you? | |

| (cont’d) | Tilly Web 2.20 | Don’t mum, you’re causing more trouble... | |

| Ben smashes door (2.20) | Sally Webb 2:20 | No, I’m being serious. | |

| 2.26 | Sally exits lounge to kitchen (right). Ben follows. | Ben Web 2:24 | [Breaking door] You’re being serious, are you? Being serious are you |

| (cont’d) | Tilly Web 2:27 | [Shouts] She’s not - Ben, she’s not. | |

| 2.29 | Camera pans right to reveal Tilly on sofa with dog. Pans further right to reveal Ben wrestling with Colin in kitchen. | Ben Webb 2:29 | ...being serious, are you? Come on... |

| (cont’d) | Colin Webb 2:30 | Leave your mother alone. | |

| 2.32 | Ben exits kitchen to lounge and punches door. | Ben Webb 2:32 | ...come on. [Punches door] |

| 2.35 | Camera moves back to reveal Sally in kitchen and Colin following Ben into lounge…Tilly foreground. | Tilly Web 2:34 | [Distressed] Ben! Stop it. Ben stop it, Ben. |

| 2.37 | ...Ben interacts with camera, forcing lens downwards. Camera pans to reveal floor and Tilly on sofa with dog. | Colin Webb 2:37 | That’s enough. Hey... that’s enough. |

| 2.4 | w/s. Static exterior Web’s house. | Ben Webb 2:35 | [Screaming] Get the fuck out of it... get the fuck out... |

| 2.46 | w/s. Static. Neighbourhood. | Colin Webb 2:37 | [Ben screaming] ... Phone the Police... [dogs barking] ... |

| (cont’d) | Ben Webb 2:39 | [Ben screaming] I’m gonna fucking kill you... | |

| Cut to black. | Tilly Web 2:41 | Ben! [Parrot squawking x several]. | |

| 2.48 | END |

There is not enough space here to fully dissect the clip, but I highlight aspects which to me typify ObsDoc location Sound Recording:

The ‘Action Space’

This is the often-counter intuitive responses to what is actually happening (time/ space-specific) within the extra-pro filmic event, manifesting itself in a fundamental response to what Cannon classified as ‘acute stress response’ (Cannon. 1915. 211) - flight v. fight? But also, ethically: to intercede or ignore? And at what points? In the case of this scene, Sound (and in fact, actual) signals strongly suggest exit from the space yet ObsDoc requires a reasoned yet counter-intuitive response for example, interactions before 2’37 - a clear example of counter-intuitive action-space-specific decisions.

Inter-protagonist

At 02’37” Ben interacts with the camera, pushing the lens down. As makers sharing space with the protagonists, working relationships are established over the 2 month’s filming period. The interaction with the camera at this point clearly indicated that this relationship had broken down: makers were no longer observing - now being involved and perhaps even inciting, and so they withdrew from the location.

Perhaps controversially, the Sound Recordist consciously yet speculatively, opted to leave the DAT recorder recording in the room as the Makers exited. In fact, this was how the ‘melt down’ ‘wild’ audio was recorded and later used at (2’41-2’48”), imposing a linear and successive sense of time on the covering exterior, night-time shot.

Inter-spatial

The required self-directed choreography between makers working around ‘action’ within an extra-profilmic event space - in this instance: small room; 2 entrances/ exits; 4 protagonists; 2 dogs; 1 parrot – privileges the unfettered flow of movement of protagonists, as their inter-relational dynamics are paramount.

Inter-makers

The Recordist instinctively understands what the camera is shooting and crucially, what the next shot will probably be. They will ‘know’ the size of shot from the lens size and the distance from subject; negotiate sources of light, etcetera – all working within a specific Action-space; facilitating two people performing collaboratively, yet individualised and autonomous roles; Sound and Camera filming independently but focused on the Story. For example, the filming choices made in the ‘glass smash’ sequence clearly indicate that it is the mother’s (Sally) story and not the son’s (Ben): the camera films its own narrative opting to privilege Sally close-up while the sound records its own contribution to the ‘audio-visual scenography’ which Chion defines as: ‘Everything in the conjunction of sounds and images that concerns the constructing of a fantasmatic diegetic “scenic space” (Chion. 2009, 469) - here, the narrative comprises 2-way dialog and ‘action’ glass smash, with meaning deriving from ‘live’ juxtaposition – or some of the ‘thousands of choices’ that Wiseman identified.

Agency and Authorship

The Sound Recordist’s agency centres around choices made in the event and specific pre-emptive selections and deployment of audio equipment; chosen and deployed explicitly to gather ‘audio signs’ so as to contribute to ‘meaning’ and to questions around the film’s text and its reception. Paul Sellors et al identify this authorial contribution as ‘utterance’ (ibid, 268), which he defines further as being the “collective authorship through theories of collective intentions”. (ibid, 268). Perhaps in a Venn diagram of ‘thinking’ (analysis) and ‘hands on’ (technical) elements, the ObsDoc Location Sound Recordist’s utterance situates in that overlap.

In the film clip example cited earlier, the Recordist chose to use a Middle & Side microphone (cardioid polar pattern and a Figure of 8 polar pattern, combined into one microphone). Some Recordists favoured the ability of M&S in ObsDocs situations, to give an ‘enhanced mono’ capability – two pick-up patterns in one microphone - for greater ‘on mic’ coverage, better suited to an unscripted filming environment. The film sound was mixed and recorded using 2003 technology - a multi (2) track Digital Audio Tape recorder and a guide mix was simultaneously transmitted to the camera, to aid on-going offline editing workflow over the 2-months shoot. The master audio was recorded independently because an ObsDoc Location Recordist requires a self-determining ability to record shot ‘run-ins’ and ‘run-outs’; wild tracks and any other speculative audio elements for later inclusion choices in the post-production arena, as evidenced in this extract:

| TIME | VISUALS | SPEAKER | DIALOG |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.4 | w/s. Static exterior Web’s house. | Ben Webb 2:35 | [Screaming] Get the fuck out of it... get the fuck out... |

| 2.46 | w/s. Static. Neighbourhood. | Colin Webb 2:37 | [Ben screaming] ... Phone the Police... [dogs barking] ... |

| (cont’d) | Ben Webb 2:39 | [Ben screaming] I’m gonna fucking kill you... | |

| Cut to black. | Tilly Web 2:41 | Ben! [Parrot squawking x several]. | |

| 2.48 | END |

As indicated, all of that sequence audio was ‘wild’ – dialog; dogs, parrot squawk etcetera. This approach of the ObsDoc Recordist fully aligns with the concept that being able to capture unscripted, spontaneous events, signifies what Berry in Robinson identifies as a commitment to ‘jishizhuyi’, or what he terms ‘on-the-spot realism’. (ibid. 1). Robinson elaborates:

In the context of documentary practice, this entails the realisation of ‘a spontaneous and unscripted quality that is a fundamental and defining characteristic distinguishing [jishizhuyi]… (ibid. 1).

Part 2 - Post Reithianism - Why the UK ObsDoc Genre Need Reinvigorating.

Over the past three decades in the UK, the production landscape for the ObsDoc genre has become re-defined and increasingly marginalised. There were three distinct contributors to, and signifiers of, the rapidly and profoundly changing socio-political zeitgeist in the UK, paving the way for the deregulation of both making and producing UK TV programs.

The first was the Peacock Committee which reported on BBC funding in 1986 and was expected by the Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher to conclude that the BBC licence fee should be abolished, although the Peacock Committee favoured retaining much of the existing system as a ‘least worst’ option. Other recommendations were that Independent Television (ITV) franchises should be put out to competitive tender; that at least 40% of the BBC’s and ITV’s output should be sourced from independent producers; Channel 4 should be able to sell its own advertising, and that all televisions should be built fitted with encryption decoders. (Peacock. 1986).

The second contributor to subsequent Acts of Parliament was the refusal of the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA) to accede to the UK Government’s demand that they ban the program Death on the Rock 1998, produced by ITV franchise-holder Thames Television, in their current affairs slot, This Week 1998. The program challenged the official line of the events surrounding the deaths of three Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) members, in Gibraltar on 6 March 1988 - killed by the British Special Air Service (SAS) in ‘Operation Flavius’. The program argued that the IRA members were shot without warning or while attempting to surrender. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was, in her own words, ‘beyond fury’ at the IBA’s decision to transmit, and later referred publicly to the effect that the IBA’s decision had on the 1990 Broadcasting Act. nb. Death on the Rock 1998 won two major awards as best documentary of 1988: BAFTA Award for Best Documentary - and an award from the Broadcasting Press Guild.

The third contributor to a radically changing UK television landscape was the UK legislation, Broadcasting Act 1990 and Broadcasting Act 1996, which began the deregulation of British Broadcasting and reversed restrictions imposed on ownership of ITV franchises. The main points of the 1990 Act were: a requirement for all ITV franchises to be put up for sale and to be awarded partly on financial grounds; Channel 4 could now sell its own advertising and therefore ITV’s monopoly on advertising sales was lost; a requirement for major broadcasters (BBC and ITV) to acquire 25% of their product externally, and the BBC to initiate an internal market called ‘Producer Choice’ where producers were required to use the cheapest facilities rather than accept those provided by the BBC itself. The 1996 Act further established regimes for the introduction of digital terrestrial broadcasting, and media ownership guidelines.

The implementation of the changes in structural regulations effected by both Broadcasting Acts, prompted a move away from the Reithian principle to ‘…inform, educate and entertain’ towards the primacy of a ‘profit-margin’ program-making ethos - after all, the post 1991 newly-won franchise holders needed to make returns on investments. Thames Television lost its franchise in that 1991 bidding round.

From the late 1990s, ITV’s long-standing remit requiring commitment to strong current affairs and documentary programming, diminished with the ending of series such as World in Action (Granada TV), This Week (Rediffusion London/ Thames TV), First Tuesday (Yorkshire TV), Network First, Survival (Anglia TV), and Weekend World (London Weekend TV). In December 2009, the final edition of ITV’s long-running arts program, The South Bank Show was broadcast.

Both commercial and Licence-fee funded UK TV in the guise of ‘Producer Choice’, looked to develop different forms of production models and the lowest cost-base production model was a vital response strategy. The first response model was multi-skilling/ self-shooting as a new wider economic reality for Factual Documentary making, and also for Observational Documentary making. This required Production Departments to self-shoot (camera and sound) - usually on pro-sumer level equipment as it was easier to learn and more mobile to use, for essentially unskilled and unwilling operators. This practice rapidly became the de facto way to make ObsDocs - small independent production companies supplying some of the now-required 25% externally sourced product. Given the de-skilled and amalgamated nature of this style of acquisition, the vast majority of self-shooters prioritised Camera over Sound Recording. This methodology gained traction and eventually, even BBC’s internal flagship strands such as ‘Modern Times’ were requiring staff Directors to self-shoot films. After many technical mishaps with missed content, the ‘Modern Times’ production process became mitigated by hiring external professional Sound Recordists - an example of which was Jewish Weddings 2008.

The second response model was the emergence of the Fixed-Rig Factual genre. Post 2000, an accelerating shift towards re-defining Factual and Observational Documentary making, as Reality/ Fixed-Rig Factual format evolved, offered documentary program makers opportunities to take the notion of ‘reality’ and package it in a more predictable, less speculative and therefore more financially robust way with its relatively low fixed cost of production. This methodology was branded as the new and more exciting incarnation of ‘ObsDoc’, further altering the landscape of UK Documentary program-making. It effectively usurped the ObsDocs content, further evidencing essential methodological and aesthetic changes to Observational program making, thus impacting profoundly on the practises of acquisition and aesthetic which this presentation seeks to describe and evidence.

Budgets for speculative and unpredictable ObsDoc projects were diverted to Fixed-Rig Factual with their finite costs and potential returns inflated by the possibilities of the Great Prize: international franchising. Creeber et al chart the changing standpoints of commissioners and makers to falling cost structures and the resulting diversion of financial resources away from some genres. (Creeber. 2015). The UK broadcasting industry sought to financially reorient itself: Park in The Guardian newspaper, in his role as Managing Director of Shed Media later taken over by Warner Bros. Television Productions UK, identified the cost of Investigative documentaries (Panorama, Dispatches) as being £140,000 per hour (1999). In today’s value, £140k would be £251k (Hargreaves Lansdown 2020). In 2016, the BBC’s defined its ‘FL2’ budget range within its categorisation of ‘Contemporary and specialist documentary - often single narrative editorial and domestic - covering singles and short series…’ as being per hour – ‘£125k – £170k’. (BBC. 2016. 5). Even at the quoted £170k per hour at the BBC’s top-end, this represents a real 47% drop that would be paid by the commissioner, over the adjusted 1999 figure of £251k per hour.

I continue to use Cutting Edge: Bad Behaviour-Ben 2003 as a focus for my argument which essentially posits that a combination of national social and political changes evidenced in the form of the Broadcast Acts 1990 and 1996, paved the way for the deregulation of both making (industrial relations) and producing (deregulation of requirements) of UK TV programs, prompting a move away from the highly speculative and costly production of Observational Documentaries, towards the market certainties of its emerging replacement: the Fixed-Rig Factual format with its attendant potential global franchising reward model.

The Bad Behaviour 2003 series started as a speculative ObsDoc, commissioned as a ‘one-off’ program, Cutting Edge: Bad Behaviour-Georgina 2003. It got an unprecedented 4.5 million viewers on C4 and so producers Lion TV, were commissioned to make a further 2-programs – each getting 3.5 million viewers, thus confirming a market success. Critical success followed with Cutting Edge: Bad Behaviour 2003, winning the Broadcast Award for ‘Best Documentary’, 2003; the San Francisco Film Festival 2004 - ‘Golden Gate Award’, and the Newport Film Festival 2004 - ‘Best Documentary’. This was a pivotal example where a successful UK ObsDoc series directly spawned a Fixed-Rig Factual format version with all its attendant ‘new world’ fiscal attractions, including finite and predictable methods and therefore costs of production, along with internationalised market appeal. And so, the spin-off UK and USA franchise Supernanny 2004 was born (Ricochet Television/ Warner Bros. Television Productions UK), and which still runs in 2020.

Factual TV, with its emerging ‘100 cameras is better than one’ ethos, spawned a new type of Observational Documentary where the ‘Fixed-Rig Factual’ approach required ‘coverage’ as an integral acquisitional process; effectively replacing the practices of single camera, classic ObsDoc story-telling skills, with new skills-sets and an ethos more akin to an Outside Broadcast-type coverage of an Event. Bad Behaviour 2003 and Supernanny 2004 illustrate this methodological change. Bell observed:

Fixed-rig productions have radically changed the way that film-makers work, giving them many more tools to work with. While old-school observational documentary directors have to make do with a couple of cameras to shoot their series, fixed-rig shows have up to 100… (Bell. 2015).

This not only re-classifies the art and craft of single camera storytelling as outdated and ineffective, but radically distorts the understanding of what typifies ObsDoc filmmaking. It renders obsolete the centrality of the relationships, choreography and agency that I described, instead identifying the creative currency of ObsDocs as now being measured in the numbers of cameras covering an ‘event’.

Freedman et al, reporting on an inquiry to examine the future of public service television in the UK in the 21st century, acknowledge that the sub-genre of:

Factual entertainment is relatively cheap to produce, popular with audiences… but it has also antagonised whole sections of the population with, for example, what has been described as ‘poverty porn’… which explore the ‘reality’ of life for some of the poorest in society. (Freedman. 2016. 106).

Chalaby observes that now:

Reality television includes a variety of categories including observational documentaries, factual entertainment, reality competitions, talent competitions and constructed reality. (ibid. 106).

A full critique of the Reality/ Fix-Rig Factual’s fiscal and ontological approaches deserves a separate paper in its own right, which I can’t develop here, but I contend that the outcome of Cutting Edge: Bad Behaviour Ben 2003 and the film’s content itself as indicative of the ObsDoc genre, would have been profoundly impacted by a fixed-rig filming approach, typified by literalism. An example being the ObsDoc clip used - the ‘glass smashing’ sequence would have been highlighted in close-up, hence losing the nuances (camera privileging mother; sound covering 2-way dialog and action) who’s meaning originates from the juxtaposition described earlier, deriving in turn from the ‘thousands of decisions’ in film-making, that gave rise to that sequence.

Part 3 – On the Cusp- Questions and Opportunities Arising.

As alluded to above, technological filmmaking advancements have been an historic enabler of content innovation, transforming how makers have utilised, developed and deployed those innovations to explore new opportunities in developing genre-specific film languages – ObsDocs being a prime beneficiary - for example: the change from 35mm film cameras to16mm film cameras; separate Sound (Nagra); Timecode; zoom lenses; radio mics and so on. As Leacock observed after shooting documentary on 35mm film cameras:

This experience gave me a goal with clearly defined standards. I needed a camera that I could hand hold, that would run on battery power; that was silent, you can’t film a symphony orchestra rehearsing with a noisy camera; a recorder as portable as the camera, battery powered, with no cable connecting it to the camera, that would give us quality sound; synchronous, not A Revolution in Documentary just with one camera but with all cameras. What we call in physics, a general solution. (Leacock. 1993).

This enabling process continues to evolve storytelling possibilities and choices, and to open new markets, as well as affect established ones too. An example was the response in 1998 to the UK launch of digital satellite and terrestrial channels was an edict from the BBC (itself broadcasting via satellite for the first time) for all PSC (portable, single camera) and documentary audio to be sourced in stereo, as the broadcast output itself was going over to transmitting all output in stereo - previously only Outside Broadcast and Live Events had been, in NICAM (Near Instantaneous Companded Audio Multiplex) - an early form of lossy compression for digital audio.

The shortcomings of recording A-B or X-Y stereo in Observational Documentaries was that the soundstage would be constantly changing as camera and microphone positions changed – even jumping 180 degrees within one picture cut. Protagonists evolved a response centring around Middle and Side (M&S) stereo microphones which were in fact used as ‘enhanced’ mono sources which could then be later ‘mono’d’ within a stereo sound balance or decoded into A-B or X-Y stereo and utilised in a post-mix, accordingly, for NICAM transmission.

And so, developments continue. The emergence of consumer accessible VR and 360-degree immersive technologies with vibrant, cross-platform experimentation, puts the emphasis on greater immersion and interactivity. There are plenty of experiments with these new technologies within the documentary form, which stem from a similar aspiration to that of the ObsDocs genre - to put the viewer ‘within’ the film space, or, to create a sense that “…there’s no separation between the audience watching the film and the events in the film.” (Wiseman in Atkins. 1976. 43). But these new experiments, as before, focus predominantly on the visual, relying largely on 360 cameras and VR or AI visual designs to create a sense of visceral immersion. I want to suggest that centring location Sound Recording around immersive capture would widen our understanding of how visceral immersion can be achieved - specifically suggesting that ambisonics would contribute to the rejuvenation of ObsDocs.

Robjohns in ‘Sound On Sound’ explains that:

Ambisonics was conceived in the late 1960s as a complete recording and reproduction system capable of recreating accurate three-dimensional sound stages from original recordings. The format was developed using complex mathematics and psychoacoustics…’ (Robjohns, 2001).

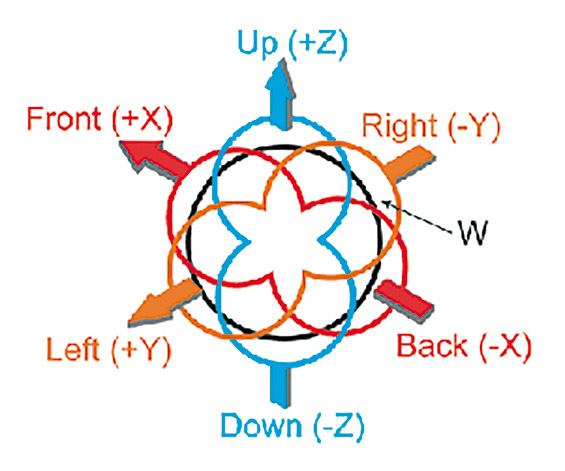

In an interview with the author, February 2019, John Leonard - a long-standing practitioner of location ambisonic recordings for Theatre Sound Design - interprets ambisonics as being “3-sets of M&S: front and back; up/down; front/side”. Ambisonics records and reproduces 360-surround sound from a single microphone source with a tetrahedral array of 4 coincident capsules, giving 4 channels (WXYZ) of audio recorded in the field, referred to as ‘A-Format’. Software in post-production converts the A-Format signal to B-Format, which allows the magic to happen - effectively, the B-Format signal become mathematically defined, virtual microphones: W (omnidirectional pattern), X (Figure-8 pattern looking forward and back), Y (Figure-8 pattern looking left and right), and Z (Figure-8 pattern looking up and down), channels.

The four Bformat signals convey everything there is to know about the amplitude and direction of acoustic signals arriving at the microphone. https://dt7v1i9vyp3mf.cloudfront.net/styles/news_large/s3/imagelibrary/s/surround1b-1001-VkJY7XfXVqetkk5Dzs6dgiI1WtimCV26.gif

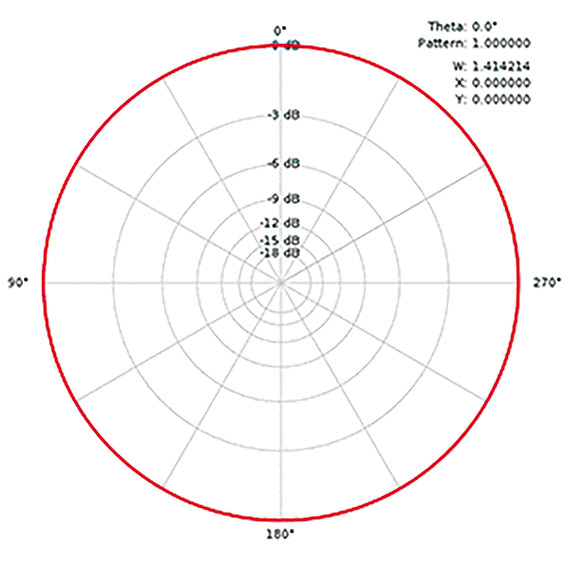

By combining these signals in various ways, it is possible to recreate the effect of any conventional microphone polar pattern (omni, cardioid, hyper-cardioid and figure-of-eight), pointed in any direction within the 360-degree audio soundscape. Furthermore, as ambisonics is ‘speaker agnostic’, a mix including B-Format signals, can then be transcoded to any transmission/ consumption format, from mono to full 360-degree immersive sound, with height information (see Binaural later).

Although flawed, an analogy for ambisonics is of an ‘audio lens’ which can be zoomed, focused, panned and tilted to fine-tune the overall sound pick-up, post event, as demonstrated in the following animated diagram:

An animation of the ‘post-steering’ pick-up possibilities of an ambisonic mic. - By Nettings at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40368483

Crucially, ambisonic microphone movement around ‘action’ is not the classic reactive mono shotgun ‘point at action/ speech’ mode: it can be moved to allow action to take place around it – nothing is ‘off mic’ post event. Crucially, this means that audio ‘focus’ decisions can be made later - software can. then steer a ‘virtual shotgun mic’ towards a sound source, giving limitless options in post, although as John Leonard observed in the same interview, in his decades of recording in the format “…if you’re a distance away from the person talking, you can zoom-in [in post] … but it’s like having a hyper cardioid pattern that’s too far away…”

Empty virtuosity?

‘The potential of the ambisonics mic is limitless and we’re only just starting to see what content producers can really achieve with it now.’ Rode, Australia (makers of ambisonic microphones) in an interview with the author, July 2019.

Leonard comments on his methodological approach to recording in the format:

Ambisonics gives me surround which is what I want, but it doesn’t give me surround in such a way that it’s distracting, which is also what I want… People are approaching it usually from a gaming point of view where people are after the wow factor… what it does have is extreme naturalness.

In the same way that other technical innovations have affected developing languages adding choice; so ambisonics. This 360-degree ‘action’ recording will provide an improved sense of space and place, bringing the location sound to bear again: perfect for the visceral and authentic aspiration to put the ObsDocs viewer ‘there’.

So how might shooting methodologies change for ambisonic-centred location sound recording, to foreground ‘extreme naturalness’ or ‘being there’, within the two main filmmaking scenarios:

The first is Separate Sound: Camera and Sound operators: a classic single camera narrative methodology, typified with a Multi mono approach: radio mics; shotgun mic; placement mics - augmented by a series of location-specific ambisonic atmosphere/ place recordings. A new Ambisonics approach could utilise the ambisonic microphone as the main ‘action’ microphone, augmented with mono sources for example, radio mics.

The second is Sound On Camera: a Single operator methodology, adhering to the self-shooting methodology for Sound Recording referred to earlier in ‘multi-skilling/ self-shooting’. This approach utilises an on-camera mono microphone which effectively ‘looks’ wherever the lens is pointing. So, to pick-up ‘on mic’ sound, the camera has to point at the source otherwise it is ‘off mic’, or to use radio microphones but with a resulting increase in complexity for the single person operator. This methodology would have affected the ‘Ben’ glass smash sequence – the smash and Ben’s dialog would have been ‘off-mic’ as the camera properly elected to privilege close-up on Sally. Or the camera chooses not to stay on Sally because it privileges other elements of audio-visual scenography (ibid. 2009, 469) which in turn, then becomes quite a different film.

As I later describe in the Opportunities for Visual Storytelling section, with ambisonic recording, the camera is liberated from needing to ‘aim’ at the sound source, and can now concentrate on shooting for the lens, thereby facilitating a more fluid camera response, now no longer dependent on inherent restrictions within the ‘single operator’ methodology described above.

With both Separate Sound and Sound On Camera methodologies, there are profound aesthetic and practical questions arising, impacting on opportunities to examine and enhance the development of the genre:

The Visceral Impact

Although the location audio can be embellished at the post-production stage, what remains crucial is the bridge between viewer and event space: being able to experience through one of the senses, an un-mediated ‘reality’. As Chesler summarised of Wiseman’s Field Sound Recording strategies:

Ambient sound, typically picked up through an omnidirectional microphone, captures the whole of a sonic environment without privileging a specific sound source in a scene. These ambiences defy logics of listening practice as all sounds within a space are captured within a 360-degree area.’

Crew; protagonists; viewers are all placed in a common sound space: the viewer is ‘in’ the Southampton house or the Iraq desert in a war situation – but could this be too visceral a viewer experience?

Storytelling and Reception

With location 360-audio comes choice for what Chion categorises as the audio-viewer (ibid, 2009. 468) to aurally focus on sound elements happening outside of the ‘profilmic event’ and then to effectively be able to select and interpret from their own ‘point of audition’ (ibid. 2009. 485) - the spatial position Chion defines from which we hear a sound. How then do the storytellers deal with an audience’s ability to process audio information (sub/ consciously) from out of vision: for example, choosing their own points of audition according to distance; clarity; dynamic; trajectory; movement; power, etc; the world which Schaeffer defines as the ‘acousmatic’. (Schaeffer. 1966. 91).

Opportunities for Audio Storytelling

Understanding Chion’s observation that unlike visuals there is no equivalent auditory frame of sounds (ibid. 2009. 470), I contend that the ObsDoc story-telling space has now become authentically immersive, effectively contributing to the audio-visual scenography of what Chion identifies as an “in-the-wings effect” as sound being located in “‘absolute offscreen’ space… to create the impression that the screen has a contiguous space.” (ibid. 478).

Opportunities for Visual Storytelling

Camera ‘coverage’ is profoundly impacted. The immersive location audio principle in ‘one person: single camera’ narrative would benefit from the re-discovering of the ‘fixed, 35mm prime lenses’ aesthetic so that the camera movement itself does the ‘zooming’ and not the lens. Zoom lenses in Single Camera ObsDoc operation, distort vision-to-audio perspectives – long lenses give close frames but distant sound, thereby challenging authenticity. This shooting methodology becomes more attuned to the audio’s ‘natural’ 360-coverage where the camera moves in to get a tight shot, and out to get a wider shot – the audio ‘frame’ will then match the visual frame and hence, enjoy a ‘natural’ perspective, thereby contributing to the visceral experience of the immersive Audio Visual content, within the pro-filmic event space.

Chion describes the audio-visual scenography as being:

…everything in the conjunction of sounds and images that concerns the constructing of a fantasmatic diegetic “scenic space” through the interplay of onscreen, offscreen, and nondiegetic - particularly through the use of entrances to and exits from the auditory field… (ibid. 2009. 469).

How might that manifest itself in camera ‘coverage’? For example, a person enters through a door in the lounge in the Southampton house, but is not in shot. In a 2D audio world, the door sound would intrude as it would appear unexplained ‘on top’ of the diegetic audio ... The camera acting as pictorial story-teller no longer ‘needs’ to explain this sound with a cut-away or a re-frame – the audio-viewer sub/ consciously ’auditions’ the sound of the door in a 360-audio world, and rationalises accordingly, placing the sound within a natural, experiential ‘world mix’. So, location immersive audio capture coincidentally liberates the camera, now no longer needing to explain and/or support audio.

Sound as Construct

Belton and Weiss observe in Johnson, that “What the soundtrack seeks to duplicate is the sound of the image, not that of the world.” (Johnson. 1985, 4). They describe a Post-production response normalising ‘natural’ as a ‘construct’, based around a typical ‘scripted’ filmmaking methodology, but in ObsDocs, questions immediately arise around authenticity - ambisonics already centralises ‘extreme naturalness’, so perhaps the quote might then be re-worked: ‘What the soundtrack seeks to duplicate is the sound of the world, not that of the image’.

Profilmic Event

As described earlier, the profilmic space is academically described by the world the lens sees. The audio equivalent is the microphone pick-up pattern. So, 360-degree location audio can facilitate audience engagement in a newly-defined profilmic space paradigm – not just what is visually in front of, but crucially, now around the lens. Might a shifting of received priorities require a commensurate academic re-definition of the term: ‘profilmic’? Or indeed, a new additional classification, for example, the ‘extra-profilmic event-space’ now describing the new 360-degrees situation-specific world?

Authorship and Agency

Both filmmaking scenarios open up a set of questions around authorship and performance. Who is now performing the filming – Camera? Sound Recordist? Director? Or perhaps now a ‘New Role’? Does a ‘fusion’ ethic better fits an emerging model around new audience, new platforms and new consumption methods? This would help define an emerging ontological response to a film language suited to 360-degree audio ObsDocs – a la Fred Wiseman, in his multi roles as Sound Recordist/ Director/ Editor, perhaps?

Does this liberated methodology now require a new response in terms of skillsets? Are the terms ‘Camera person’, ‘Sound Recordist’ and ‘Director’ now to be merged and re-titled: Content Acquisition Artist, or Maker, or similar?

What is the effect on the agency of the Sound Recordist, now consciously assessing, augmenting and recording a 360-environment, and so telling their ‘story’ in a new, developing language? As the coincidental liberation of the camera now no longer needing to explain and/ or support audio, the resulting shift in authorship/agency hierarchical-based assumptions, would then align with Gaut’s assertion that the authorial should be ‘multiply classified’ (ibid), and to provide a definitive response to Sellors’ question: ‘Is the sound recordist a member of a film’s collective authorship? (ibid), around the Sound Recordist’s utterance, described above.

In any case, the ‘New Role’ - Content Acquisition Artist / Maker - foregrounds sound story-telling skills but now with a required empathy with the 360-Sound world of the extra-profilmic event-space; understanding what is and isn’t achievable on location and therefore in post; the ability to understand how ‘post-mic-steering’ will work, etcetera, as well as having visual story-telling skills – now filming for audio, perhaps? Is this approach now ‘Sound on Camera’ or ‘Camera on Sound’, or simply ‘Audio Visual’?

Conclusion

Although Michel Chion was writing on post-constructed soundscapes, location-recorded ambisonics furthers the audio-viewer’s ‘choice’ principal and adds to the visceral nature of the audio-visual scenography that he describes. As hypothesised, the role of ambisonic-centred Location Sound Recording in the ObsDoc genre, centralises multi-agency and multi-authorial craft/arts, aspiring to immerse the audio-viewer in a position closer to the reality that is being observed, so “there’s no separation between the audience watching the film and the events in the film.” (ibid. 1976. 43). The ability for a speaker-agnostic ambisonic sound mix to fold down to any audio format including, crucially, binaural (stereo audio with height information ie immersive), can be experienced on now ubiquitous devices with stereo headphones, as well as domestic ambisonic sound bars. This continues the evolution in an audience’s potential ability to consume ObsDocs, but now in a multi-platform, multi-screen world. Crucially, it facilitates the rediscovery of single ‘sound/ camera’ ObsDocs story-telling skills. Ambisonics will contribute towards the reinvigoration of a new ObsDocs format for Makers, now no longer tied to the framing of 1xhour specials on terrestrial TV with their speculative and high cost-bases, but now a reimagined version of for example, UK Channel 4’s ‘3-Minute Wonders’ series for new documentary Makers, or Instagram-length micro-docs. These micro ObsDocs could be consumed by the audio-viewer on their device, while for instance, travelling on the proverbial (and actual) Clapham Omnibus, but now immersed ‘’within’ a 360- audio film space and truly experiencing “…no separation between the audience watching the film and the events in the film.” (ibid. 1976. 43).

Bibliography

C. Paul Sellors. 2007. “Collective Authorship in Film.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 65, no. 3. Accessed April 21, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/4622239.

Gaut, Berys. 1997. “Film Authorship and Collaboration”, In Film Theory and Philosophy, edited by R Allen; M Smith, 149-172. Clarendon Press.

Chesler, Giovanna. 2009. “Truth in the mix: Frederick Wiseman’s construction of the observational microphone”, edited by Eva Hohenberger, 139-155. Vorwerk 8. Revised. 2012. Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, No. 54.

Chesler, Giovanna. 2012. “Truth in the mix: Frederick Wiseman’s construction of the observational microphone”. Last modified Autumn, 2012. http://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/jc54.2012/CheslerDocyAudio/

(Barnouw 1993: 235)

Robinson, Luku. 2002. ‘Contingency and Event in China’s New Documentary Film Movement’, no. 199, 1–30.

Winn, David. 2014. 31st Annual News And Documentary Emmy Awards Lifetime Achievement Honoree: Frederick Wiseman. The National Academy Of Television Arts And Sciences. http://emmyonline.org/news/news_31st_interview_wiseman.html Last access on 25/04/2020.

Cutting Edge; ‘Bad Behaviour – Ben’ (2003)., Directed by Hilary Clark., UK: Channel 4. TV Broadcast.

Behaviour Change Consultancy. 1997. “Step by step guide to his unique behaviour change system.” Accessed Mar 2020. http://www.behaviourchange.com/

Cannon, Walter Bradford. 1915. Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear and Rage. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Chion, Michel. 2009. Film, a Sound Art. Translated by Claudia Gorbman. Columbia University Press. 469.

Report of the Committee on Financing the BBC (Cmnd 9824). 1986. Chairman: Professor Alan Peacock.

Death on the Rock (1988)., Series Editor, Roger Bolton. UK: Thames Television. TV Broadcast.

Broadcasting Act 1990, Chapter 42.

Broadcasting Act 1996, Chapter 55.

Creeber, Glenn. 2015. Television Genre Book Editor(s): PART VIII: REALITY TELEVISION- 49. Intro. British Film Institute.

Park, Brian. 1999. “It’ll cost how much?”. The Guardian, 3 Aug, 1999.

Hargreaves Lansdown. 2020. “Calculator.” Accessed 24Feb, 2020. https://www.hl.co.uk/tools/calculators/inflation-calculator

BBC. 2016. BBC tariff range of indicative prices for the supply of commissioned television programmes - (5) http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/commissioning/site/tariff_prices_for_independents.pdf

Powell, Nick. 2005-20. Supernanny. Ricochet/ Warner Bros. Television Productions UK.

Bell, Matthew. “How fixed-rig has transformed factual.” Television magazine, Royal Television Society, Feb, 2015.

Freedman, Des. D. J. 2016. A Future for Public Service Television: Content and Platforms in a Digital World. Project Report. Goldsmiths, University of London. [Report]

Who Benefits? Poverty Porn. 2013. Edinburgh International Television Festival.

Chalaby, Jean. 2016. The Format Age: Television’s Entertainment Revolution, Cambridge, Polity.

Leacock; Richard. 1993. 1960 A Revolution in Documentary Film Making as seen by a participant.

Atkins, Thomas R., ed. 1976. Frederick Wiseman. New York: Monarch.

Robjohns; Hugh. 2001. Surround Sound Explained: Part 3. Ambisonics. SOS Publications Group.

Schaeffer, Pierre. 1966. Traité des objets musicaux. (91).

Johnson, William. “Film Quarterly Vol. 39 No. 1, “Review of Review: Film Sound: Theory and Practice”, by Elisabeth Weis, John Belton. University of California Press Journals, Autumn, 1985. 46-48.