Abstract

This research aims to use Bernard Tschumi’s cinematic approaches to offer a different reading of architecture in which architectural language is not limited by precise and generative drawings, rather the organic behavior plays a significant role. Space, movement, and events are the main pillars of Tschumi’s The Manhattan Transcripts, where conventional components of architecture are broken down and rebuilt along different axes. This paper addresses architecture schools in Egypt that convey conventional architectural methodologies to students in the form of a market-driven intellectual economy without challenging the presumed focus on form either through abstraction or simulation. Eventually, the purpose is to introduce the notations of experience and time for all forms of intervention in the reading of the physical environment.

Keywords: Bernard Tschumi, Architecture Education, Cinema, Pedagogy, Manhattan Transcripts.

Introduction

The Western modernist paradigm proved its dominance over local values and general philosophy. The very core of Disneyfication1 encouraged extreme individualist movement and defined a novel chapter in the consumption culture, clouding itself over collectiveness and societal values. Such a trend has succeeded to penetrate intellect convincing the inner members to follow its trail, eventually giving rise to terminologies as “American dream” or “land of opportunity” (El-Husseiny and El-Husseiny 2012, 3). This philosophy insulated a desire for show, power, and ecstasy that spread its cultural effect during the twentieth century emphasizing the importance of technology, scientific development, commodities, materialistic appearance, and ease of life. Architecture has followed a similar route, specifically within the Arab context. Al-Masiri referred to the Arab’s reaction to widespread materialism as partial secularism (Al-Masiri 2011, 69-70), where the state’s management preserved its seclusion from religious issues. This paved further steps for intellectual autonomy defining a culture of its own. Architecture in the Arab context became a tool for self-expression and elite status. The excessive use of new glazed offices and curtain walls was a reflection of individuals’ stylish cars and lavish lifestyles, i.e. a genuine transformation in the communities’ socio-cultural framework.

The open-door economic reform that took place in Egypt during the late 1970s and early 1980s gave more space for privatization which has penetrated the urban perimeter of cities, especially Cairo, developing projects such as commercial centers and office buildings (Salama 1999, 2). No longer is architecture a direct communication with inhabitants, but rather a formalistic economic necessity that emphasizes form over essence. As a result, architecture education has adopted such a formalistic approach within its milieu by excluding alternative forms of art and effort. Nikos Salingaros questions the intentions of modernist educational institutions2, “The system is desperately trying to protect its sovereignty – not by improving its methods, but by ruthlessly eliminating any competing ideas” (Salingaros 2007, 93). In other words, according to Salingaros, architecture schools embraced materialist intellect that corresponds to post-modern outcries rather than innovation and creative meaning.

This paper explores the post-modern architecture education in Egypt and aims to tackle the conventional materialistic perspective by providing an alternative approach to reading the physical environment. Eventually, the paper attempts to answer a single, yet complicated, question: What is the missing element in architecture education that can revive essence and human-environment connectivity?

We do not talk about Space in Architecture

The talk about space in architecture stems from a sense of discontent with modernism’s traces in the built environment. Koolhaas (2002, 175) defines the product of modernization as Junkspace, “[it] is what remains after modernization has run its course, or, more precisely, what coagulates while modernization is in progress, its fallout”. The newly-born form of architecture has been continuously criticized for lacking essence, specifically for degrading the role of space in foregrounding architectural value. It is not new that studies of architectural space are an integral part of contemporary interdisciplinary research. Space, being an articulated entity, has gone through a transformation of perception among different periods (Michelis 1949, 72). From the Egyptians, the Greeks, the Gothic, the Renaissance, all the way to the present time, the conception of space changed from a one-dimensional existence to a four-dimensional one (Michelis 1949, 72). Thus, architecture has come to include the metaphysical being of its experience, i.e. the spatial praxis.

The concepts of space can be traced back to as far as Aristotle who first assessed that space is a product of the intertwined relationship between body and objects3 (Jammer 1993, 17). Archytas distinguishes between space and matter – space is an independent entity from matter (Jammer 1993, 10). Furthermore, he defined space as “not some pure extension, lacking all qualities or force, but is rather a kind of primordial atmosphere, endowed with pressure and tension and bounded by the infinite world”4 (Jammer 1993, 10). Further interpretations of space were recorded, most significantly was during the nineteenth century when German art historians of the Einfühlung (Empathy)5 realized the spatial condition resulting from the movement of the body (De Aguiar 74, 2006). The position of the body within space, as well as its performance within, naturally gives it an extra dimension where interaction between the walls, the bodies, and the physical objects occur – hence, the term spatiality. The concept of spatiality, simply put, is a combination of the geometry (space) and the topology (movement) (De Aguiar 74, 2006). This perspective was further developed during the early stages of the modern movement. The Bauhaus school, as acknowledged by French philosopher Henri Lefebvre, realized that things do not exist autonomously but there exist spatial interrelationships with the whole universe around (Lefebvre 1991, 63). Amongst those of the Bauhaus was Alexander Klein whose work follows the line of spatial arrangements by elaborating diagrams that describe lines of movement. Taking a similar route, even further, was Swiss architect Le Corbusier, emphasizing the instrumental value of axes and their role in spatial ordering. He writes,

An axis is perhaps the first human manifestation; it is the means of every human act. The toddling child moves along an axis, the man striving in the tempest of life traces for himself an axis. The axis is the regulator of architecture. To establish order is to begin to work. Architecture is based on axes (Le Corbusier 1986, 187).

Le Corbusier regards the architectural plan as the main instrument in the organization of architecture and urban form. It is then that a new language of composition, induced with space and movement, emerges.

Bernard Tschumi: Space, Body & Movement

In line with the post-structuralist thinking, American architect Bernard Tschumi acknowledges the kinesthetic importance of space, body, and movement. His approach to spatiality induces a form of paradox – the paradox of ideal space and real space, i.e. mental process and social praxis respectively. Tschumi’s body of theory claims that such paradox stems from the folding and unfolding of both aspects in a “Panglossian world where social and economic forces are conveniently absent” (Tschumi 44, 1994). It is almost impossible to question the nature of space and experience a spatial praxis at the same time. Just as architectural avant-garde has always fought opposites, e.g. structure & chaos and reason & intuition (Tschumi 43, 1994), this paradox is addressed by Tschumi through highlighting the subjective experience of space as being its very concept (Savic 2012). For Tschumi, space does not exist without event, and architecture does not exist without a program. The event6 is a conceptual tool that is capable of transforming the program into a spatial experience through the movement of bodies. Claiming that architecture is not an expression of mere structural extant, Tschumi emphasizes the nature of architecture as a performance, a means of communication; “it becomes a discourse of events and spaces” (Savic 2012).

The Pyramid, the Labyrinth & the Visuals

Foregrounding essence over form is Tschumi’s main theoretical aspiration in the sense of re-evaluating the role of architecture in the practice of personal freedom. The foundation of this approach is connectivity and dynamism, as there is no fixed relationship between architectural form and the events taking place within it, instead it is a dynamic and conflictual relation. Tschumi’s Manhattan Transcripts explore this relation as an attempt to re-narrate an architectural understanding of reality.

The Manhattan Transcripts seek to reveal an internal logic underlying buildings and cities. Through focusing on unnecessary activities, e.g. luxury, arts, games, etc. and extracting from them the notations of movement, Tschumi reveals the dynamic behavior of architecture. This philosophy attempts to overcome the paradox of architecture, identified with the dualism of the pyramid and the labyrinth. According to Hollier, both the pyramid and the labyrinth represent “the war between copula and substance”7 (Hollier 65, 1989). The pyramid is the domination of idea over matter, it resides within conceptual and dematerialized reason where the subject is detached from the object (Clinical Observation 2010). It is argued that the pyramid is the architecture added to the building inducing justification and economy. On the other hand, the labyrinth is the space of sensations that is directly connected with the subject’s sensory experience, hence the materiality of space is foreground.

The Manhattan Transcripts are a development of Tschumi’s visual language, which shows plans and elevations of architectural spaces and schemes of movement. There exists a crossover between Tschumi’s vision and that of filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein whose diagrammatic methodology – Tschumi’s main source of inspiration – evolved into ideas of movement through space (Jadoon 7, 2015). Eisenstein’s essays form a crucial link between the static viewer and the cinematic screen, where the viewer moves across a realm of spatial imagination across different time and space, furthering his argument by claiming that the viewer absorbs and connects with visual space while experiencing architecture. Such absorption is maintained through the montage technique that concurs Baudelaire’s emphasis on irregularity, saying,

That which is not slightly distorted lacks sensible appeal; from which it follows that irregularity – that is to say, the unexpected, surprise and astonishment, are an essential part and characteristic of beauty (Baudelaire 1930).

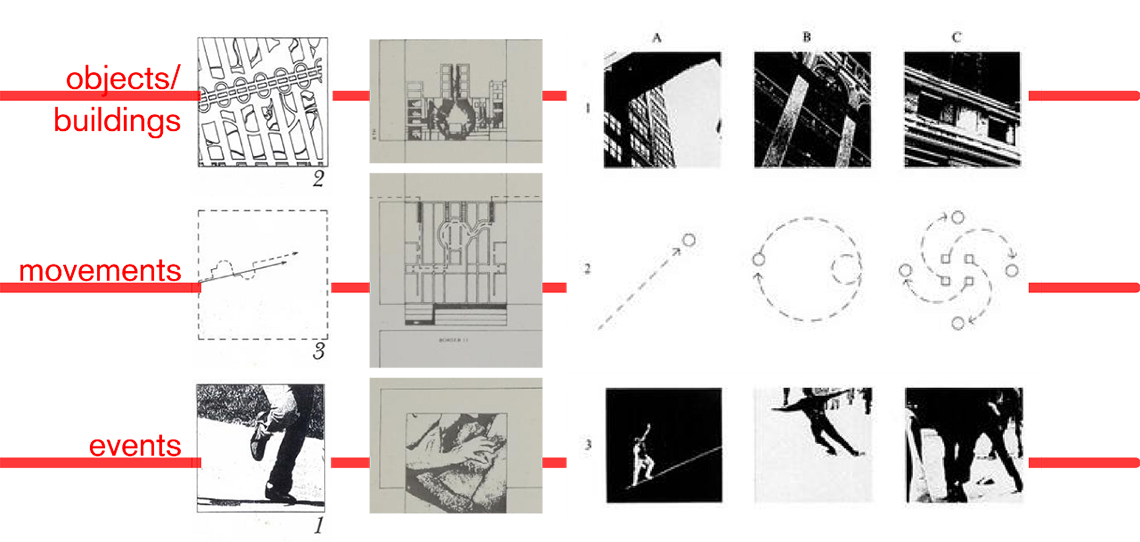

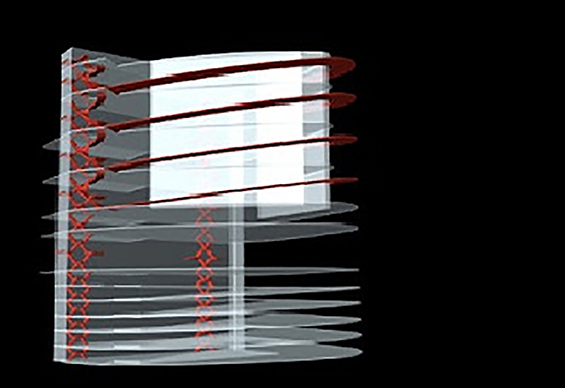

Both Tschumi’s transcripts and Eisenstein’s films (Image 1) trace the different movement of people walking around an architectural spatial ensemble that does not depend on a single frame but a succession of frames or spaces (Jadoon 10, 2015). Their use of the frame contradicts its purpose of maintaining an equal of normality, rather they acknowledge the single unit frame as “healthy, conformist and predictable, regular and comforting, correct” (Savic 2012). A succession of frames and spaces produces a succession of dynamism and conflict, retelling spatial reality and defining a new perception of design. Both tend to tackle paradox by strengthening reason and material together.

Image 1 – Tschumi’s Transcripts (Top) and Eisenstein’s Films (Bottom) adopt a similar technique in tracing the movement of bodies in space. Eisenstein’s montage theory is an inspiration for Tschumi’s work in using a succession of frames to enhance dynamism. Source: Socks Studio, 2011

Books of Architecture, not Books about Architecture: The Teaching Process

It is at this point that the paper suggests an alternative technique to the teaching process for architecture students. Schools of architecture, specifically in Egypt, follow a conventional technique that emphasizes formalism over spatial. Students are assigned to a set of tasks to be fulfilled that concur with the conventional mental image of architecture, e.g. software renders and ‘photoshopped’ post-production images (Image 2), without giving much attention to what happens inside the building, and what kind of events that compose the functional behavior of the structure. It is a process that degrades architecture to a static entity devoid of dynamism and character.

Image 2 – A student’s architecture project for a Revit course that emphasizes form over movement. Arab Academy for Science Technology & Maritime Transport, Cairo, Egypt. Source: Autodesk, 2019

Furthermore, architecture institutions in Egypt seem to lack the emphasis on what goes beyond the field of architecture, e.g. the study of humanities and visual arts. A comparative study was carried out by Attia, Zayed & Elkhouly (2016) between three Egyptian universities – Cairo University, Ain Shams University, and Al-Azhar University – where they compared the programs taught in the architectural departments. The results showed that the total number of hours completed by students for humanities courses does not exceed an average of 5 hours/week. Furthermore, Cairo University is the only institution that includes visual studies in its curriculum (Attia, Zayed & Elkhouly 11, 2016).

According to Hotiet (1970), the educational curricula of the schools of architecture in the Arab World are based on traditional approaches to design ranging between two models, the Black Box and the Glass Box. According to Jones (1970), the Black Box model takes place within the mind of the designer lacking any sort of justification or comprehensibility, while the Glass Box is the transparent design process that, though can be justified, may not provide convincing justifications for each phase undertaken (Jones 50, 1970). The Glass Box may seem to be the better approach, yet it is associated more with objectivity, which contradicts the production of space as a subjective method. In other words, unlike the Glass Box, objectives, variables, and criteria are not fixed. What is worse is the continuous demanding nature the architecture industry has become. This can be observed in the springing of several commercialized projects and rows of residential units that lack spatial convenience and visual connectivity. The architectural design process has undergone a militarized operation embedded with a hardcore globalized economy that a few neighborhoods have been transformed into an open-air shopping mall.

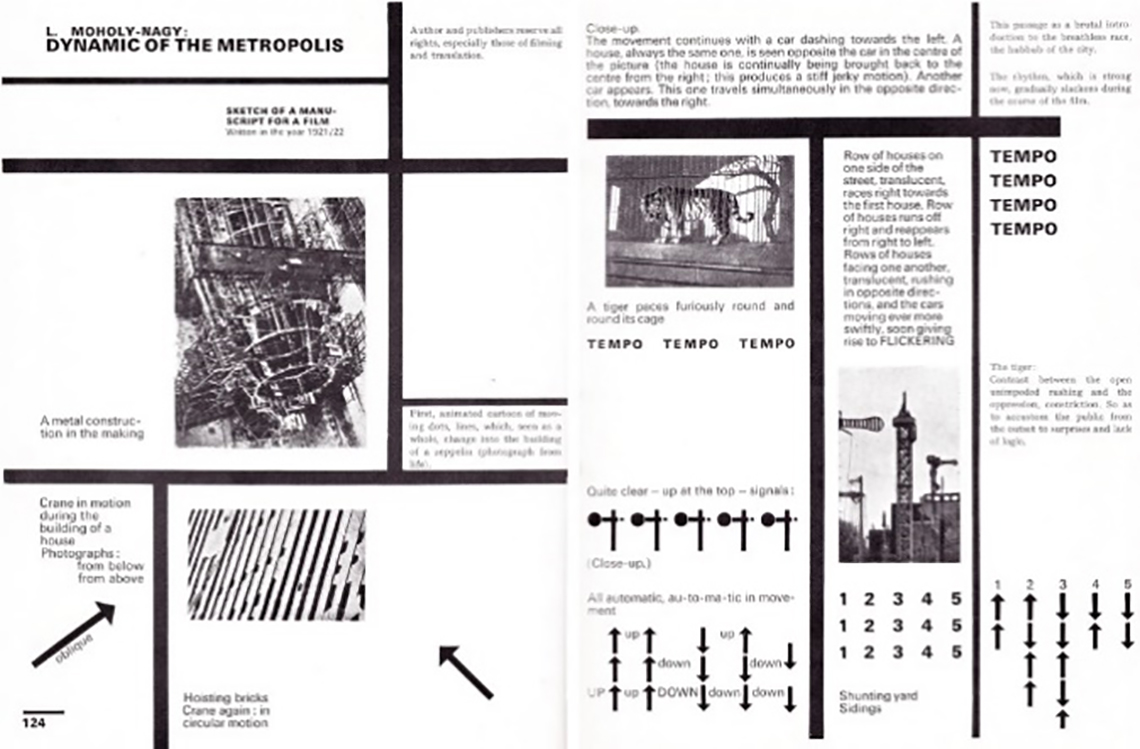

There is a crossover between Tschumi’s intro words in The Manhattan Transcripts (1994) and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s unfilmed experimental scenario Dynamik Der Gross-Stadt (The Dynamic of the Metropolis). Moholy-Nagy opposes the literary action theatrical feature, instead “[he] aspires to attain a ‘dynamic of the optical’ with ‘much movement, some heightened to the point of brutality” (Dimendberg 113, 2003). In its visual appearance, Moholy-Nagy arranges a series of photographs within irregularly sized grids of squares and rectangles separated by thick lines going horizontally and vertically (Image 3). These grids make use of the background white space by directing attention to the complete surface of the page (Dimendberg 114, 2003).

Image 3 – A sample of Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s design arrangement of his photographs to engage the viewer with the dynamic city. Source: Bauhaus Bookshelf, 2019

Moholy-Nagy rejects having any logical connection between the elements of the scenario, claiming that they merge into a sequence of events occurring in time and space engaging the audience with the city’s dynamic feature (Moholy-Nagy 122, 1969). Tschumi’s speculative yet convincing words reinforce Moholy-Nagy’s theoretical arrangement,

They can be theoretical projects, abstract endeavors aimed at both exploring the limits of architectural knowledge and at giving readers access to particular forms of research (Tschumi 6, 1994).

Breaking down the Conventions

In Tschumi’s extensive theoretical writings, architecture does not exist without words. This laid the basis for the introduction of the deconstructivist intellectual figure within the architectural theory (Hu, Wang & Xue 2223, 2014). His Manhattan Transcripts convey a Jacques-Lecoq-like8 salute to architectural processing. Moreover, they are an attempt to question the modes of representation of architectural techniques that are commonly used among architects, e.g. plans, sections, and perspectives. The Manhattan Transcripts were eventually a product of Tschumi’s breakdown of architectural conventions giving more freedom to each new part autonomously in line with the modern narrative (UK Essays, 2018). The plans of the Park, the section of the Street, and the perspective of the Block all follow an internal logic of their own and widely differ from the traditional method of representation.

This breakdown provided the readers/audiences to be engaged with the imagery of the events. The images have undergone a theoretical move “from the optic to the haptic and from sight to site in architecture” (Bruno 6, 2002), aka Einfühlung. Coming into contact with elements creates what German philosopher Gernot Böhme calls the Atmosphere – the ability to sense space without being physically in it (Farsø & Petersen 67, 2015). Similar in process, cinema images are manufactured images, which include spaces within which the performances of characters are predefined. Cinematic space is created, deconstructed, and re-created by the audience, a methodological tool that emphasizes the importance of imagery as a “[representation] of a whole world, which is reflected in it, as in a drop of water” (Tarkovsky 152, 1987). Like a filmmaker, Bernard Tschumi plots architectural drawings that are not architectural, i.e. relying on unnecessary routine activities, e.g. running, exercising, etc. to deconstruct space into the narrative and the artistic. He tends to break traditional guidelines of contemporary representation, and replace it with abstract thinking that includes: 1) De-structuring, emphasizing the structure of the building rather than the aesthetics, 2) Superimposition, which strengthens the previous point via opposing all that architecture stands for, i.e. anti-hierarchy, anti-structure and anti-form, and 3) Contextualization, as opposed to what was believed during the 1980s and 1990s that context is mere visual content (Paul 154, 2014).

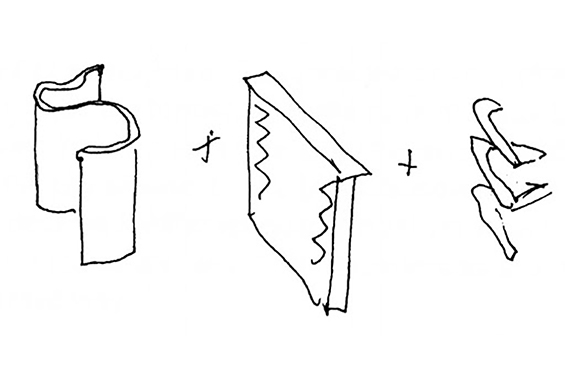

Tschumi’s sketch for the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sao Paulo, and its position next to a digitally reproduced image of the museum (Image 4), reveals an interesting distinction made by Walter Benjamin between the graphic and the geometric line, claiming that the graphic is always more solidified than the geometric (Bois 178, 1990). This comparison introduces an insightful reading into the imagery useful for the distinction between what is raw and naked and what operates within the realm of art. Just like a succession of frames in a film, “the reader follows a montage-like placement of drawings next to a filmic image” (Hartoonian 30, 2010). The appearance of a freehand sketch right next to a digitalized model reveals Tschumi’s preference for abstraction and his avoidance for any organic or aesthetic theatrical surfaces. He emphasizes the slow process of creativity as opposed to the draftsman product having no concern for space and time. Forms are not homogenous in Tschumi’s Manhattan Transcripts and grids produce non-totalization.

Image 4 – Tschumi’s sketch for the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sao Paolo (Top) and his digitalized product of the building (Bottom). By displaying them together, Tschumi insists on the inorganic value of the sketch, one that puts concern for space in its creation. Source: Bernard Tschumi Architects, 2001

Conclusion

This paper attempted to define an alternative technique to teaching architecture. Architectural schools have always focused on the end product more than the process, leading to a known phenomenon of static architecture, i.e. lacking essence, movement, and value. Looking at Bernard Tschumi’s work, The Manhattan Transcripts, his theory uses the notion of human movement to create forms. His methods are quite cinematic, as it adopts the montage theory – the succession of frames – into the work of architecture, giving readers the flexibility to move around and explore spatial construction. However unfamiliar and disjunctive Tschumi’s work might seem, it holds together every line and every axis with the surroundings. Finally, this paper suggests a further study exploration into the crossover techniques between Bernard Tschumi, Sergei Eisenstein, and Jacques Lecoq that would be used as a valuable handbook for architecture students.

Final Notes

1In Sociology, the term Disneyfication describes the transformation of a society to resemble the Walt Disney theme parks as a result of Western-style globalization. The term received intellectual attention through the essays of French Philosopher Jean Baudrillard who called Disney Land the most real place in the United States, referring to the other places as being hyper-real or simulated.

2At the beginning of the academic year in 2004, the architecture and urbanism department at the Catholic University of Portugal in Viseu witnessed a sudden shift in the curriculum from traditional to modernism. Since then, most of the European architecture schools have adopted the same approach.

3Aristotle’s spatial views claimed that place does not exist without the embracing body. A theory that originated from his interpretation of what the Pythagoreans did with numbers. Quite the contrary were Plato’s point of view, whose material autonomous perspective was the denominator in the analysis of objects.

4Archytas once posed a question of whether one can stand on the edge of a sphere’s circumference and stretch his hands. He was the first to provide proof for an infinite extension. Thus, his theory of the world moving in void replaced Democritus’ idea of the cosmos being a limited spherical sphere.

5The concept of Einfühlung (Empathy) was first coined in 1872 by German philosopher Robert Vischer. It was the psychological interpretation of architecture, where the spatial experience is directly related to a human’s emotional and psychological basis.

6The concept of the event, being an integral component of spatial architecture, was first developed by Austrian designer Paul T. Frankl through his book Principles of Architectural History: The Four Phases of Architectural Style, 1420-1900. In his book, Frankl claims that the purpose of architecture is the provision of a logical path for a definite sequence of events.

7In linguistics, a copula is a linking verb between the subject of a sentence and the subject complement, e.g. the word is in a sentence. Similar to the atoms and molecules in chemistry or protons and electrons in physics, a substance is the actual element of language. They can be the phonic (sound) and graphic (written) aspect of language.

8Jacques Lecoq was a French stage actor best known for his ‘negative way’ teaching method which was a critique of the unacceptable aspects of a student’s performance. This method would encourage performers to create new avenues of expressive movement.

Bibliography

Attia, Sahar, Zayed, Mohammed, & Elkhouly, Aya. 2016. “Compatibility between Architectural Education and Professional Practice in Egypt”. Presented to Rethinking Architectural Education, Cairo, Egypt.

Baudelaire, Charles. 1930. Intimate Journals. Translated by Christopher Isherwood. New York: Random House

Bois, Yve-Alain. 1990. Painting as Model. Massachusetts: MIT Press

Bruno, Giuliana. 2002. Atlas of Emotion: Journeys in Art, Architecture, and Film. New York: Verso

Clinical Observation. 2010. Tschumi’s Architectural Paradox: Of Oppositions and Differences. http://clinical-observation.blogspot.com/2010/02/tschumis-architectural-paradox-of.html. Last access on 25/04/2020

De Aguiar, Douglas Vieira. 2006. “Space, Body and Movement: Notes on the Research of Spatiality in Architecture” in Arqtexto/Propar, 8: 74-94

Dimendberg, Edward. 2003. “Transfiguring the Urban Gray: Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s Film Scenario ‘Dynamic of the Metropolis’. In Camera Obscura Camera Lucida, edited by Richard Allen and Malcolm Turvey, 109-127. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press

El-Husseiny, Aly and El-Husseiny, Ahmed. 2012. “Spirituality and Social Values Vs Material Formalism: An Approach to a Human Architecture” in Social and Behavioral Sciences: 1-12

Farsø, Mads & Petersen, Rikke. 2015. “Conceiving Landscape through Film: Filmic Explorations in Design Studio Teaching” in Architecture and Culture, 3(1): 65-86

Hartoonian, Gevork. 2010. “Bernard Tschumi Draws Architecture” in FOOTPRINT Drawing Theory: 29-44

Hollier, Denis. 1989. Against Architecture: The Writings of Georges Bataille. Massachusetts: MIT Press

Hoteit, Aida. 2016. “Architectural Education in the Arab World and Its Role in Facing the Contemporary Local and Regional Challenges” in Canadian Social Science, 12(7): 1-7

Hu, Yinan, Wang, Yongping & Xue, Yun. 2014. “Influence on Design Education by the Architectural Trend of Deconstructivism” in Applied Mechanics and Materials, 638-640: 2222-2225

Jadoon, Musa. 2015. Architecture, Film, and Movement. Essay. Edinburgh College of Art

Jammer, Max. 1993. Concepts of Space: The History of Theories of Space in Physics. New York: Dover Publications

Jones, Chris. 1970. Design Methods. London: Wiley

Koolhaas, Rem. 2002. “Junkspace” in OCTOBER 100: 175-190

Le Corbusier. 1986. Towards a New Architecture. New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

Lefebvre, Henri. 1991. The Production of Space. Cambridge: Blackwell

Michelis, P.A. 1949. “Space-time and Contemporary Architecture” in the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 8(2): 71-86

Moholy-Nagy, Laszlo. 1969. Painting Photography Film. Translated by Janet Seligman. London: Lund Humphries

Paul, Riya. 2014. “Appraisal of the works of Bernard Tschumi”. Presented to Sustainable Constructivism: Traditional vis-à-vis Modern Architecture, New Delhi, India, 26-27 April

Salama, Ashraf M. A. 1999. “Contemporary Architecture of Egypt: Reflections on Architecture and Urbanism of the Nineties”. Presented to Architecture Reintroduced: New Projects in Societies in Change, Beirut, Lebanon, 24-27 November

Salingaros, Nikos. 2007. Anti-Architecture and Deconstruction. Delaware: ISI Books

Savic, Selena. 2012. Event and Movement in Architecture. The Manhattan Transcripts: Theoretical Projects. http://emperors.kucjica.org/event-and-movement-in-architecture/. Last access on 19/04/2020

Tarkovsky, Andrei. 1987. Sculpting in Time. Athens: Nefeli editions

Tschumi, Bernard. 1994. Architecture and Disjunction. Cambridge: MIT Press

Tschumi, Bernard. 1994. The Manhattan Transcripts. London: Academy Editions

UK Essays. 2018. The Manhattan Transcripts by Bernard Tschumi. https://www.ukessays.com/essays/architecture/the-manhattan-transcripts-analysis-architecture-essay.php. Last access on 06/05/2020