Abstract

Films often tries to portray or represent historical events and the dominant mode of representation is the pursuit of an authenticity feeling. No matter whether it is a documentary or fiction, the goal is to give the audience an authentic experience about the historical event. This paper will compare two films, one documentary and one fiction, about the 22. July terrorist attack at Utøya in Norway where 69 youths were killed. The two films are “Reconstructing Utøya” (2018) directed by Carl Javer and “Utøya 22nd July” (2018) directed by Erik Poppe. This article will discuss the concept of authenticity in general and investigate which artistic strategies the films use in the search of the authenticity tone.

Keywords: Authenticity, Narrative theory, Film-style, Analysis.

The terrorist attack

On 22 July 2011, a bomb exploded outside the government buildings in central Oslo. The perpetrator was a Norwegian far-right terrorist. After the bombing, he went to the island of Utøya, just outside Oslo, where the Labour Party’s youth league was holding its summer camp. Disguised as a police officer, he murdered 69 people, mostly teenagers, in the course of 72 minutes.

Introduction

“You will never understand this” is the opening statement from the protagonist in the film “Utøya 22nd of July” (2018). Then the audience is taken through the 72 minutes of horror at Utøya where the terrorist shoots on everybody and in the end manage to kill 69 youths. The director Erik Poppe said that he wanted to bring the audience out on that island and let them experience the massacre from the youths’ perspective. It was also important to show the element of time, time itself; thus, filming the story in one long take (Poppe, 2018).

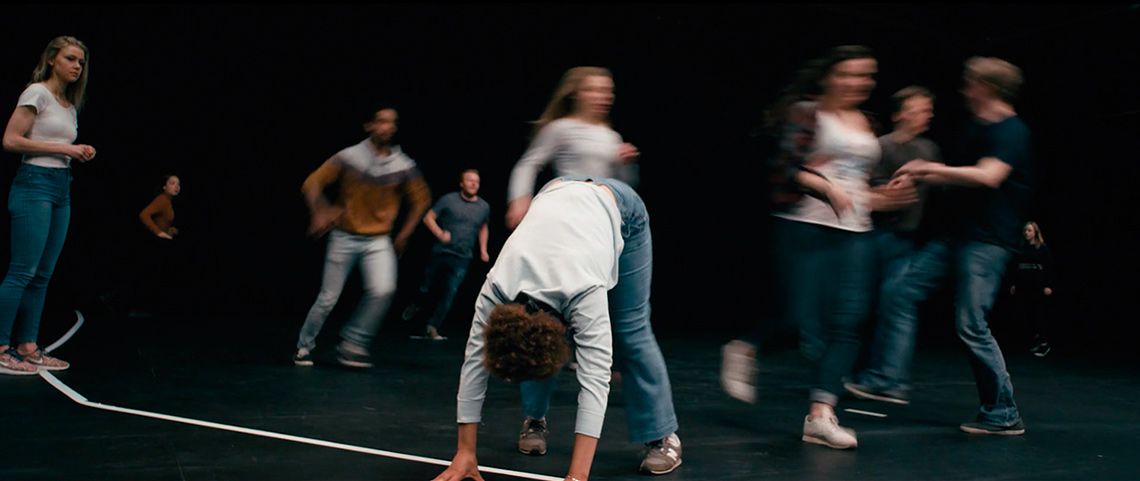

Director Carl Javer had a different approach in his documentary film “Reconstructing Utøya” (2018). Four survivors, together with 12 young amateur actors, tries to reconstruct some scenes from the terrorist attack. The scenes are recreated on a stage at a film camp in the north of Norway and the film follows this process.

When you encounter an event like the one that took place at Utøya you approach it with painful memories. It is an emotional place to enter. The ambition with the reconstructions have been to make these memories possible to film and perhaps to take control over the things that happened, conquer the fear by sharing the burden and making it easier to carry (Javer, 2018)

Both films have the ambition to make the audience feel and understand the fear and shock that the youths went through, the goal is to give the spectator an authentic experience, but their strategies are very different. This paper will seek to shed light on the differences using theoretical concept of authenticity and narrative analysis.

The modes of authenticity

In the Cambrigde dictionary the definition of authenticity is “the quality of being real or true” and this connects well to many filmmakers’ goal when making a movie. It also inherently bonded to documentary film and the indexical quality og the cinematic image. Several scholars have analysed documentary in terms of narrative, ideology and affect (Gaines, 2006; Nichols, 1991, 1994; Plantinga, 1997), and linked this to the construction of ‘truth’ (e.g. Rabinowitz, 1993; Williams, 1993) or the presentation of history (Rosenstone, 2006). However, not so many have considered the different mode of authenticity and how this influence the reception both in documentary and fiction films. The expression of authenticity is widely used in a wide range og academic fields like archeology, musicology, psychology and philosophy. Here, I will try to summarize and define the concepts used in cinema studies and especially how it is used in films of historical events and memories of these.

Two distinct understandings of authenticity appear to be at work in cinema, the first relating to the referentiality of events and objects, and the second to the affective response of the viewer. Pirker and Rüdiger (2010) also note two modes of authenticity in popular representations of the past: the mode of the authentic witness (original objects, eyewitnesses and auratic places); and the mode of the authentic experience (replicas, copies, re-enactments and reconstructions that are not necessarily originals, but which evoke a feeling of authenticity). They argue: “whereas in the witness mode, the object as a representative of the past is the core focus, in the experiential mode, the subject and his or her feelings and life world are central” (Pirker 2010, 17). In other words, the reception of the event or story is as important as the knowledge that the events, places and persons really are real.

The authenticity is also related to power or who has the authority to authenticate. Construction of authenticity is related also to power. As Edward Bruner argues, “the more fundamental question to ask … is not if an object or site is authentic, but rather who has the authority to authenticate” (Bruner, 1994). This can be an allegory for narrative power, meaning the ability for a film to be felt authentic: The story of the film was true to itself.

In many Hollywood movies the authenticity is a part of the marketing as well.

Authenticity, as the engine of mainstream historical filmmaking, has three chief functions: as an aesthetic strategy, a reception discourse and a marketing discourse. A feeling, a form of perception and (supposed) knowledge, the aesthetic success of authenticity, and thus the mainstream historical film, is assessed via the following question: Has the past been conveyed in a way that the spectator can reconcile with his or her perception of the historical reality? Audiences speak of films that “bring

history to life”. I call this condition – this sensation of a media-produced, purportedly successful historicity– the ‘authenticity feeling ‘. (Frey, 2018)

One recent example is the Sam Mendes film “1917” that has been branded to give the spectator a real experience of first world war. The script was inspired by “fragments” of stories from Mendes’ grandfather, who served as a “runner” — a messenger for the British on the Western Front. The filmmakers shot the film in southwestern England, where they dug about 2,500 feet of trenches — a defining characteristic of the war’s Western Front — for the set. Paul Biddiss, the British Army veteran who served as the film’s military technical advisor and happens to have three relatives who served in World War I, taught the actors about proper techniques for salutes and handling weapons. He also used military instruction manuals from the era to create boot camps meant to give soldiers the real feeling of what it was like to serve (Time magazine, 2019). All this to create both an authority of authenticity (places, props and characters) and an authenticity experience.

In his book “Dokumentarfilm und Authentizität. Ästhetik und Pragmatikeiner” (1999), Hattendorf describes the fictional and non-fictional elements in documentary cinema and tries to describe the mutual relations between documentary and feature film. For this purpose, he uses the term “authenticity”, which helps him to clarify the accumulated questions relating to the border area between these two types of film. He describes the semantic range of the word, using such terms as “credibility”, “genuineness”, “truthfulness,” and giving the contexts in which, it is used (e.g. law, theology, and philology). Hattendorf remarks that there are two possibilities for relating it to the film and formulates two definitions. He writes as follows:

(1) “Authentic” refers to the objective genuineness of events, which are depicted in film. Guarantee that the occurrence is authentic implies that filming didn’t influence depicted event. The authenticity is grounded in the source of depiction.

(2) Authenticity is a result of applying cinematic techniques. “Credibility” of depicted events depends on the influence that the cinematic strategies exert on viewers. Authenticity is grounded equally in form and in reception. (Hattendorf, 1999)

The first definition has to do with the cinematic apparatus and the fact that the footage has an indexical link to the mise-en-scene or for documentary, the historical world. This link is for many the key feature of a documentary, like Bill Nichols puts it.

Documentary films speaks about situations and events involving people(social actors) who present themselves to us as themselves in stories that convey a plausible proposal about, or perspective on the lives, situations, and events portrayed. The distinct point of view of the filmmaker shapes the story into a way of seeing the historical world directly rather than into a fictional allegory

(Nichols, 1997)

The last phrase here is interesting because in many ways this is the big difference between the two films. Reconstructing Utøya is seeing the historical world directly whereas Utøya 22nd of July is a fictional allegory. However, as I will show in the analysis, the borders are not that clear. Especially in the documentary of Javer, the main narrative element is the reconstruction of the events from Utøya played out by actors on a black box stage under instructions of the survivors. So, the reconstructions are in fact fictional allegories.

A concept of authenticity

If we put together the two modes of authenticity from Pirker and Rüdiger with Hattendorfs definitions we can summarize a concept of three distinct parts.

- The authentic witness (original objects, eyewitnesses and auratic places). The fact that we, as an audience know that the character is a historical witness and that historical places has an aura of emotional authenticity.

- “Authentic” refers to the objective genuineness of events, which are depicted in film. Often referred to as the indexical link in a documentary

- The authentic experience. The way the director use cinematic techniques and narrative organization to give the viewer an authentic experience of the diegesis. No matter if the diegesis refer directly to the historical world or a projected fictional world

The third is the most complex and difficult to analyze, but I will try to differentiate between the perceptually concept of presence and immersion and the narrative emotionality.

Presence

Presence can be considered a feeling of “being here”, the mind apprehends and perceives the body senses and experiences the external world around. This is an unmediated form of presence; to be present in one owns life. However, with the advent of Virtual Reality, we can speak about mediated presence as a feeling of “being there”. This is, of course, connected to the mediums ability to create perception cues so the cognitive processing of that diegesis is believable. Recently, this concept has been deconstructed into place illusion (the original meaning of the terms telepresence or presence)—the sensation of being and operating at a remote or virtual place; and plausibility—the illusion that what is happening is really happening (Slater, 2009). In her article Immersiv Journalism De La Pena writes the following on the use of VR and the potential of Place illusion (PI) and plausible illusion (Psi)

An important role of immersive journalism could be to reinstitute the audience’s emotional involvement in current events. We have identified three major factors in virtual reality that could contribute to immersive journalism that may potentially lead to greater audience involvement: PI, being in the place, Psi, taking events as real, and most crucially the transformation of the self, in terms of their body representation into a first-person participant in those events. (La Pena, 2010)

This audience involvement is exactly the goal of most film directors and especially for historical films it is important with an accuracy of events and a feeling of authenticity as well. The third point of La Pena brings us to the experience of both the story and the audio-visual perception of the diegesis in what I define as a “narrative paradox”.

Narrative perspective and levels

The degree of presence may be more prominent in VR, but the use of long takes in cinema has always been considered to give an impression of presence and immersion (especially on a big screen). The narrative paradox can be described as “the conflict between traditional narrative structure and the degree of freedom VR offers a user in movement and interaction” (Trageton 2017). More elaborated it is a question of focalization and narrative perspective. The degree of immersion often rests in the narrator’s ability to manipulate the audience into making assumptions on where the story is going and what is happening next. In a novel, the author can choose to what degree he is going to describe the scene or just focus on the characters’ thoughts or on important events that unfold. These jumps in narrative perspective is thus powerful tools to advance the story.

Edward Braningan define narration as a key to understand the complex communication of a film experience.

Narration is the overall regulation and distribution of knowledge, which determines how and when the spectator acquires knowledge, that is, how the spectator is able to know what he or she comes to know, in a narrative. A typical description of the spectator‘s position of knowledge includes the invention of speakers, presenters, listeners and watchers who are in a position to know and to make use of one or more disparities of knowledge. Such“persons” are convenient fictions, which serve to mark how the field of knowledge is being divided at a particular time. (Branigan 1992, 76)

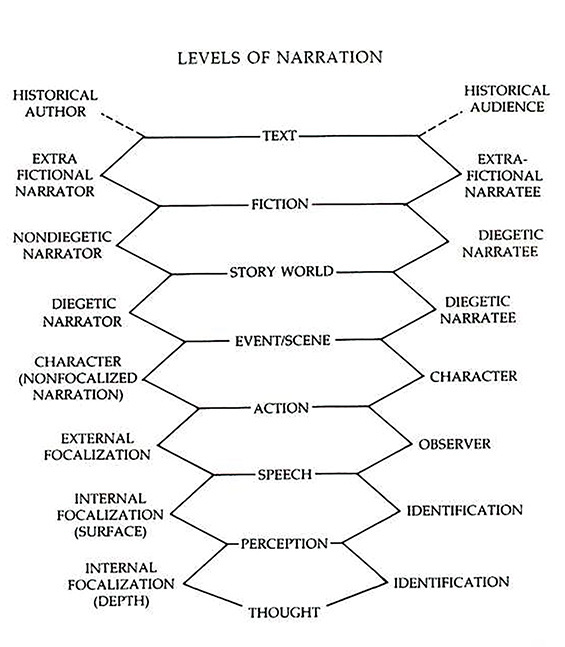

Branigan then proposes a model with up to eight levels of narration/focalization which explains both the relation between the narration and the narrator/focalizer as well as the more cognitive effects. (Branigan 1992, 87)

Figure 1 Levels of Narration (Branigan, 1992)

I will use this model in the analysis to explain the specific differences between the two films and how they use narrative structure.

Analysis Utøya 22nd. Of July (2018)

The film starts with the following text:

Friday 22nd of July 2011 Norway was hit by to terrorist attack

One car bomb placed outside the governmental building and the massacre at AUF (the labour party youths’) camp at utøya

The culprit was a 32 years old ethnic Norwegian rightwing activist.

Then a fade to black and a new text appear

22nd of July

Oslo, time: 15.17

Then follows a helicopter shot with an overview of Oslo city and some authentic surveillance footage when the actual bomb goes off. After we see some news footage of the chaos that emerge in the first minutes.

This opening builds up the authenticity feeling and also the authority of the film. It signifies that this is not “based on” or “inspired by” type of film. Until now it seems more like a classical documentary film intro.

At Time code 2:17 a new text appears

Utøya

Then we get the first shot accompaigned with birds chirping and outdoor atmosfere

Image 1 opening shot at Utøya

Then a new text on black background

Time: 17:06

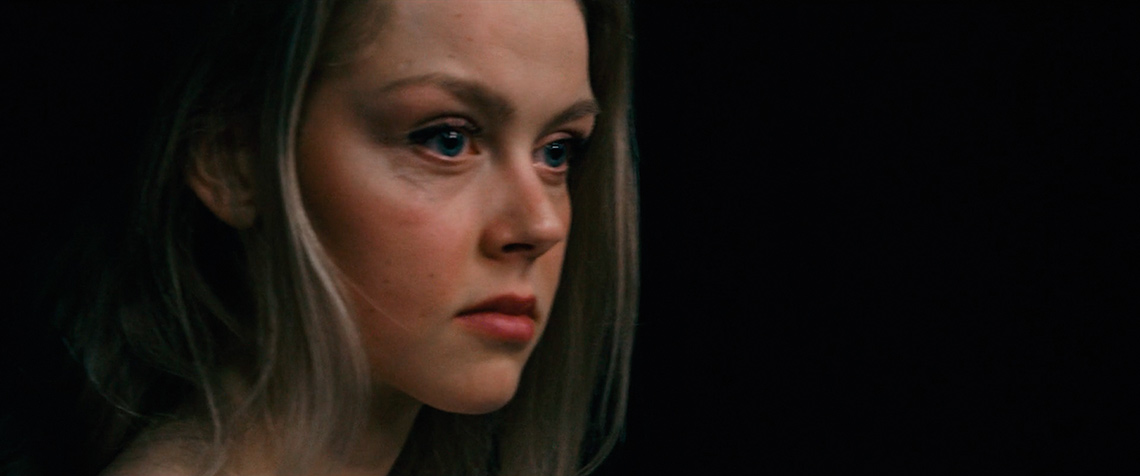

Then at TC 3:29 the protagonist Kaja enters the frame and look direct at the audience thus breaking the fourth wall.

Image 2 Protagonist Kaja

She states: “You will never understand.”

This is a very powerful use of narrative levels were the fictional character breaks out from the diegesis and talks directly to the audience. It creates a Brecthian verfremdung effect and give a clear thematic message about the context of the film. It breaks with the natural goal of the director to bring us into the diegesis, but it also functions as a bridge between the real footage used in the opening to the fictional footage in the rest of the film.

As the protagonist turns her head it is revealed by the earplug and phone sound that she is talking to her mother. A smooth transition from an extra fictional narrative level to the films diegesis level is done without an actual cut.

Image 3 Kaja reveals the earplug

From here the camera follows the protagonist in one long take, 72 minutes, and the director Erik Poppe stated the following about the choice:

When words can describe parts of what it was like to be out there, they are limited. But the emotional impact and emotional story of how to bring the audience out there on the island to describe how this young people realized which situation they were in. When I realized that what happened on 22nd of July could be limited the to what happened on that island and that I wanted to show it from those young people perspectives entirely. I wanted to show a one long take based on the fact that they were out there for 72 minutes without anything happening (meaning no help from others). I wanted to show it in a long take to show the time, time itself. Which is hard for us to show in film. We can express almost anything in a film today, but the function of time is hard to describe. (Poppe 2018, Berlinale press conference)

Poppe describes a three folded goal. To bring the audience out on the Island, in other words a high feeling of perceptual presence and authenticity. Then show the experience from the perspective of the youths, meaning both narrative perspective and focalization. Then lastly the function of time, a perceptual and narrative real time experience.

Based on the critiques and feedbacks from the audience, it seems that Poppe ambitions were fulfilled. The Norwegian press were generally very positive. The Norwegian paper DN (Todays news) praise the documentarian quality and presence.

“Utøya, July 22nd “ does not dramatize, it does not have time to dwell or disperse sequences that could have been exploited for the sake of the drama. The camera is present from just before the first confusion after the shooting has begun and until the incident itself is over. We get death up close, but without spectacular facts and special effects.

(DN, 2018)

Film scholar Anne Gjeldsvik did qualitative interviews with audiences as well as analyze the reception of the film in the media, and she argues that the film was an extraordinary event at Norwegian cinemas.

When participants are asked to describe the film in their own words, intensity, realism and verisimilitude is characteristics mentioned by most. Some scenes are highlighted as particularly strong or emotionally touching; the scene of the young dying girl in the forest that Kaja is trying to help, the phone call Kaja joins her mother as she hides behind a tree

(Gjeldsvik, 2018)

The film does not use non-diegetic music and the realism in the sound-design was pointed out by many of the informants.

The audio side works clearly as a source for the viewers to understand and feel the horror of the youngsters in the film: “Yes, sound. The strong sounds. Shout when someone was shot and shout between them and the panic, they were panicking, and the film captured that. So, I really want to say that the sound was a powerful experience. Not just the shots, but the sound of fear (Gjeldsvik, 2018)

Poppe and sound designer Gisle Tveito timed the shots and they were fired to the same extent and pace as happened at Utøya, and all the actors would hear them on the film set (Poppe, 2018).

The narrative perspective was also mentioned, the fact that the audience are stuck with a limited perspective and does not know where the perpetrator is. It is almost like a computer game where the spectator is trying to escape from the killer, but at a same time it is not; It is a story where we follow Kaja’s battle to find her sister without getting caught. Here, I would argue, we are at the core of the films narrative problem and in general the misunderstanding of subjective cinema. As Truffault aptly put it: ‘A subjective camera is the negation of subjective cinema.’

To illustrate this, I will use Branigans model of narrative levels. At TC 21:57 the camera throws itself down to the ground. Then for a moment looks up, imitating a POV shot from an invisible character thus becoming internal focalized. Normally one would cut from a close-up of Kaja and then a point of view shot of what she is looking at. This would make the transition from external focalized to internal more subtle and the audience would not consider the camera self-reflexive like the former situation.

Image 4-5 camera behaves like a POV character

Scholar Murray Smith observes that often viewers will say ‘I could really identify with character X’ or, alternatively, ‘the film left me cold - I mean I couldn’t identify with any of the characters’ (Smith 1995: 1) and, accordingly, Smith has defined a structure of sympathy: (1) recognition, (2) alignment , (3) allegiance. In Poppe’s film I would reason that the identification with the character is undermined at the expense of perceptual feeling of authenticity. Through the use of long take, realistic sound design and a self-reflexive camera the feeling of presence is indeed high. I will show later, in Carl Javers film, that a more dynamic use of narrative levels and not focus on perceptual audivisual presence will create a different authenticity feeling.

Historical places have an emotional aura of authenticity and in Poppe’s film it seems that we are on the historical site of Utøya, but in the behind the scenes of Utøya (2018) Poppe explains that another island is chosen because of its manageable size and topography. However, he states that it was important to have an Island that looks like the original. Most of the audience would infer that this was the actual historical place and add a layer of authenticity to the experience. Through the knowledge from news articles and TV reports the audience would have expectations on how the diegesis should look like and it would not create the suspension of disbelief if the film was shot differently. The topography with open meadow, woods and rocks close to the sea creates a visual dynamic that compensates for the lack of dynamic in narrative levels. This give the experience of the film a bodily quality described well by an informant

For me, it was an incredible physical experience first and foremost. I never think I’ve experienced a more stressful experience in the cinema. I sat with raised shoulders in two thirds of the movie. I sat tense, so it was physically tiring to see it ... Then I cried a little along the way. It was a kind of crying, not because I was touched, but because I was upset (Gjeldsvik,2018)

To sum up, the film had an emotional impact with the Norwegian audience and the film uses cinematic strategies to give the spectator an authentic experience. The interesting point is that it does so, more with perceptual audiovisual tools, than narrative structure.

Reconstructing Utøya (2018)

The film opens with the following rolling text on black background

On 22 July 2011, a bomb exploded outside the government buildings in central Oslo. The perpetrator was a Norwegian far-right terrorist. After the bombing, he went to the island of Utøya, just outside Oslo, where the Labour Party’s youth league was holding its summer camp. Disguised as a police officer, he murdered 69 people, mostly teenagers, in the course of 72 minutes. 56 of them were executed with a bullet to the head. How can we understand?

And then the following

Six years after the terrorist attack, four survivors from Utøya meet in northern Norway to remember and share their experiences of what happened. They are joined by twelve young Norwegians who want to help and understand. A psychologist is involved throughout the entire project. Together, in a film studio, they reconstruct the survivors’ memories of what happened on Utøya. The survivors tell their story for their own sake, but also for ours. For the present, but also for the future. This film documents that process.

This opening explains both the history of the incident and the context for the film. In addition it spells out the motivation for making this film “… for their sake, but also for ours. For the present, but also for the future”. It is almost like a preface in a documentary book. The text clearly states that this is a documentary “this film documents that process”. In Poppe`s film this transition into the fictional diegesis is inferred by the shift in narrative levels as showed in the above analysis.

Also this film starts with a helicopter shot, not over oslo, but over the film camp that lays in idyllic nature in the north of norway. The image is accopaigned with birds chirping and a positive gitar plucking.

Image 6 opening helicopter shot

After the opening credits we are introduced to the first of the 4 survivors in the film, Rakel

Image 7 Establishing shot Film camp

Rakel is talking in the phone. She is describing here expectations and excitement to be here and to meet the other youths.

Image 8 First survivor, Rakel

We follow Rakel when she meets the others for lunch, and she starts to talk to them and explain the importance of this reconstruction as mental exercise:

I’m trying to view this as a sort of psychological workout. When you do physical workout, you’re breaking down your body. Then after recovery you are stronger than before (Rakel, TC 5:05)

This opening sequence serve many functions. Just the sheer knowledge that the audience know that she is an actual survivor gives an important authenticity value. As mentioned in the introduction about the two modes of authenticity: ‘whereas in the witness mode, the object as a representative of the past is the core focus, in the experiential mode, the subject and his or her feelings and life world are central’ (Pirker 2010, 17). Actually, Javer uses both these modes in his film. The fact that Rakel is now going to get into some of her worst memories builds empathy and dramatical anticipation for what is to come.

Image 9 Close up shot, Rakel

In the next sequence we go straight to the preparation of the stage where the reconstruction is going to play out. Rakel is mapping out the terrain with white scotch. There is no typical exposition part with sit down interviews and flashback from her own upbringing. This emphasis the perception of here and now and thus also the authenticity feeling that Poppe used in his film; the function of time and space.

Image 10 Rakel is preparing the stage

The stage seems very inauthentic as a place for the reconstruction, but it invites the audience to focus more on the story and the interpretation of events and moreover the reactions from the survivors on their own memories.

The film is divided in 4 chapters where the 4 survivors recontruct their stories from Utøya. I have therefore deliberately only the first chapter where Rakel is the protagonist. Reconstructing Utøya also got generally good reviews in Norway and the film won the Swedish cinema award “Guldbaggen” both for best film and best directing. But some reviewers criticized the use of reconstruction because it gave a notion of theater play.

There are some reconstruction experiments that have become famous. “Reconstruction Utøya” brings to mind a documentary with the opposite sign, “The Act of Killing” from 2012, where some of those behind the mass killings in Indonesia in the sixties are asked to reconstruct some of the killings they committed. It initiates strange processes, a responsibility that becomes difficult to escape without the filmmaker having to put it on them.

But in that case, it was about getting someone to relate to the choices they had made. “Reconstruction Utøya” is about those who became victims. They have less to search within themselves for. It obviously costs them a lot to relive what happened, and it is unclear what Javér will accomplish with this move.

The teenagers who listen to the four are also obviously heavily affected. But when they lie down on the floor and pretend to swim, or crawl on what is supposed to be a rock, it makes the mass murder more distant, not closer. It makes it appear like theater, which is vital to remember that it was not. (Dagbladet, 2018)

This shows how difficult the notion of authenticity is, because for some, a documentary with staged reconstruction can never be authentic, but for others the same reconstruction can give a deeper authentic experience than an audiovisual presence style-oriented fiction film, like Poppe’s “Utøya 22nd July”. I will now try to show, through a micro analysis of one of the four chapters, how the reconstruction can create an authentic experience as described by Hattendorf.

Blurred realities

S. Jones writes the following on the use of reconstruction in the German film Gezicht zur Wand (2009)

The reconstructions similarly blur the two levels of time, filming present locations as if they were still past, and in the service of a narrative about the nature of the Stasi and its political relevance for contemporary Germany. Moreover, there-enactments of the past are a reconstruction of victim experience for the most part: the film replicates transport to the prison, entering the prison wing, the interior of the cells and the heavy door closing and locking (Jones, 2012)

This strategy is very common in historic documentary. Auratic locations are used to give the film authority to authenticate and through the witnesses’ retelling their experiences the viewer get a sense of experience the past. Javer does not use this strategy, instead he makes a clear point using a black box stage, that this is indeed a reconstruction. However, the strength with this choice is that the audience can focus on the telling of the survivor and the reactions on what they have experienced. All this respecting the unity of time and space which enhance the feeling of presence.

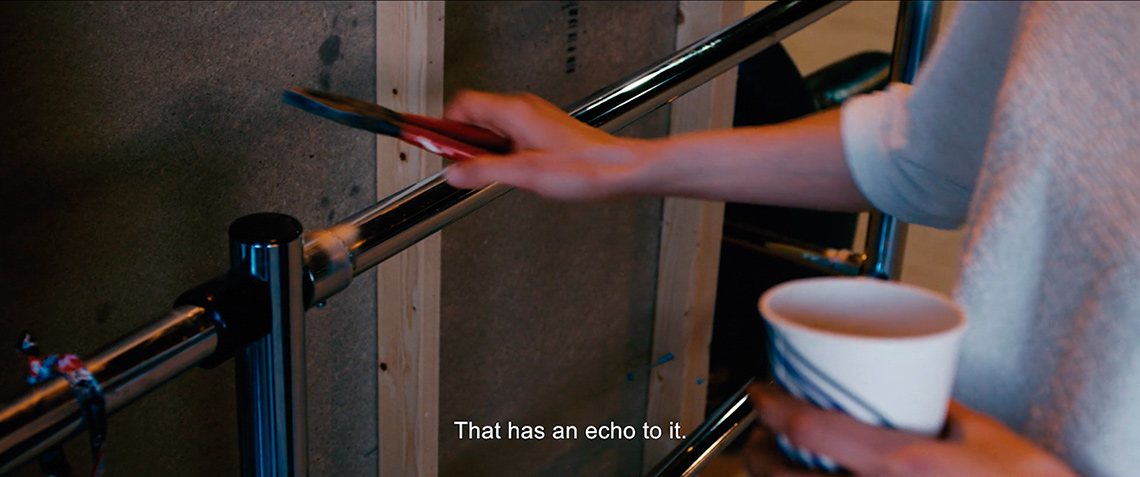

At TC 07.38 Rakel is searching to find a sound that can represent the firing gun used by the terrorist.

Image 11-12 Rakel search for the right sound to represent the shooting.

This sound is the only effect which is used during the reconstruction and the emotional impact is formidable. At TC 15.05 Rakel explains the scene to the actors; The moment where she meets the terrorist and sees him murdering a young boy. Then everybody is panicking and tries to save their own lives. During this scene the narrative perspective is steered toward Rakel and her reaction to the events.

Image 13-14 The scene and reaction shot of Rakel

If we use Branigans model we can appreciate the complex narrative situation. We are presented a documentary story world by a non-diegetic narrator in an observational style cinema that follow the process of the reconstruction. Within this world there is the diegetic narrator, Rakel, that tells her story of the events at Utøya. We as an audience can experience the events from the past played out in front of our eyes in a non-focalized manner at the same time as we see Rakel’s reaction external focalized to those memories in present time. I would argue that the authentic experience lays in the reactions of Rakel and her reliving the horror from Utøya. The artificialness of the stage is unimportant because we have been aligned with Rakel and her fight to overcome her own trauma.

Conclusion

As stated in the introduction I wanted to study how the two films “Utøya 22nd of July” and “Reconstructing Utøya” used different strategy to obtain a feeling of authenticity. One fiction and one documentary with the goal to affect the audience and give them the perspective of the victims.

Through the analysis of Poppe’s film I have showed how the use of long-take, realistic sound-design and the absence of non-diegetic music can create a high degree of presence and thus authenticity feeling. The bodily experience reported by spectators supports this view. However, I would also argue that the typical alignment or allegiance with the protagonist is weakened by the cinematic style with a limited choice of narrative levels. The POV is subjective, but it does not create a POV structure of sympathy as Smith describes. Another aspect I would reflect on is the power of extra diegetic knowledge. One reason why most of the viewers, at least in Norway, were so emotionally affected by the film lays in their own memory of the real-world events. Hundreds of articles, news reports and witness descriptions of the terror attack forms a strong emotional context of what happened, and the audience come to the movie with a strong emotional context. For other audiences, that does not have the same national memory of trauma the film may lose bit of its experience authenticity. Some international reviewers addressed this.

The characters in the film are fictionalized but based on the accounts of real survivors; fine to protect their identities, but dubious to deliberately twist the narrative to create additional sympathy. A scene that sees Kaja softly singing Cyndi Lauper’s True Colors, for example, is played for maximum pathos, as if the killing of 77 people, mainly teenagers, isn’t tragedy enough. (The Guardian, 2018)

In “Reconstructing Utøya” the authenticity of the witness plays an important part. The witness authenticity of the objects, buildings and remembering individuals creates the potential for the emotional and experiential authenticity. They ascribe significance and offer an apparently direct link between past and present. At the same time Javer manage to combine this with the objective genuineness of events in an observational style documentary. The choice of doing reconstruction like a theater, with behind the scene footage gives Javer the opportunity to recreate the past terror into a present time drama where the strength lays more in the protagonist fight for overcoming the trauma. The experienced authenticity with the audience is double layered. One can see the events from Utøya re-enacted, like in Poppes film, and at the same time feel the inner conflict of the protagonists about coping with memory. There is even a third layer in the film on how the youth amateur actors react to the same memories and how they try to help the survivors.

Paradoxically Javers documentary does not exploit the emotional power of auratic locations or archive footage that other documentaries normally do, whereas Poppe’s film does exactly this. Therefore, one can describe Poppes’s film as using the authentication strategy of documentary and Javer’s film using the authentication strategy of narrative fiction.

Bibliography

Bruner EM (1994) Abraham Lincoln as authentic reproduction: A critique of postmodernism. American Anthropologist 96(2): 397–415.

Branigan, Edward 1992. Narrative Comprehension London: Routledge.

Frey, Mattias “The Authenticity Feeling.” (2018).https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-AuthenticityFeeling/8018a205c26b84b110ff069a5176ccf453a17350

Gaines, Jane M. 2006. Collecting visible evidence.

Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press.

Hattendorf, Manfred. 1999. Dokumentarfilm und Authentizität: Aesthetik und Pragmatik einer Gattung. Konstanz: Oelschläger.

Jones, Sara. 2013. “Memory on film Testimony and constructions of authenticity in documentaries about the German Democratic Republic”. European Journal of Cultural Studies. 16 (2): 194-210.

Nonny de la Pena, (2010) Immersive journalism, Presence, Vol. 19, No. 4, August 2010, 291–301 © 2010 by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Nichols B (1991) Representing Reality: Issues and Concepts in Documentary. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Nichols B (1994) Blurred Boundaries: Questions of Meaning in Contemporary Culture. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Nichols, Bill. 2017. Introduction to documentary. Bloomington, Indiana : Indiana University Press

Pirker EU and Rüdiger M (2010) Authentizitätsfiktionen in populären Geschichtskulturen: Annäherungen. In: Pirker EU, Rüdiger M and Klein C et al (eds) Echte Geschichte: Authentizitätsfiktionen in populären Geschichtskulturen. Bielefeld: transcript, pp.11–30.

Plantinga, Carl R. 2010. Rhetoric and representation in nonfiction film. Grand Rapids, MI: Chapbook Press.

Rabinowitz P (1993) Wreckage upon wreckage: History, documentary and the ruins of memory. History and Theory 32(2): 199–137.

Rosenstone RA (2006) History on Film/Film on History. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Williams L (1993) Mirrors without memories: Truth, history, and the new documentary. Film Quarterly 46(3): 9–21.

Slater, M. (2009). Place illusion and plausibility can lead to realistic behaviour in immersive virtual environments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 364, 3549–3557 doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0138

Smith, Murray. 1995. Engaging Characters: Fiction, Emotion, and the Cinema. Engaging Characters: Fiction, Emotion, and the Cinema. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Press coverage

Berlin filmfestival 2018 press Conference https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2rrRocjac0I

Dagens Næringsliv. 2018 Film review «Utøya 22. Juli» https://www.dn.no/film/anmeldelser/erik-poppe/utoya-22-juli/anmeldelse-av-utoya-22-juli-god-og-aldeles-for-javlig/2-1-278092

Dagbladet. 2018 Film review «Reconstructing Utøya» https://www.dagbladet.no/kultur/hvorfor-ma-egentlig-utoya-ofrene-utsettes-for-dette/70303989

The guardian. 2018 Film review «Utøya 22nd July» https://www.theguardian.com/film/2018/oct/28/utoya-july-22-film-review

Filmography

Poppe, Erik. 2018. Utøya 22. juli 72 minutter som endret oss for alltid. Oslo: Nordisk film.

Javér, Carl. 2018. Reconstructing Utøya. Vilda Bomben Film AB, 2018

Paradox. (2018). Utøya 22. juli, Behind the scenes. Fetched from https://www.apple.com/no/itunes/